Excited (and nervous) to give a Zoom lecture today to a 5th-grade class about astronomy in ancient Mesopotamia and its legacy!

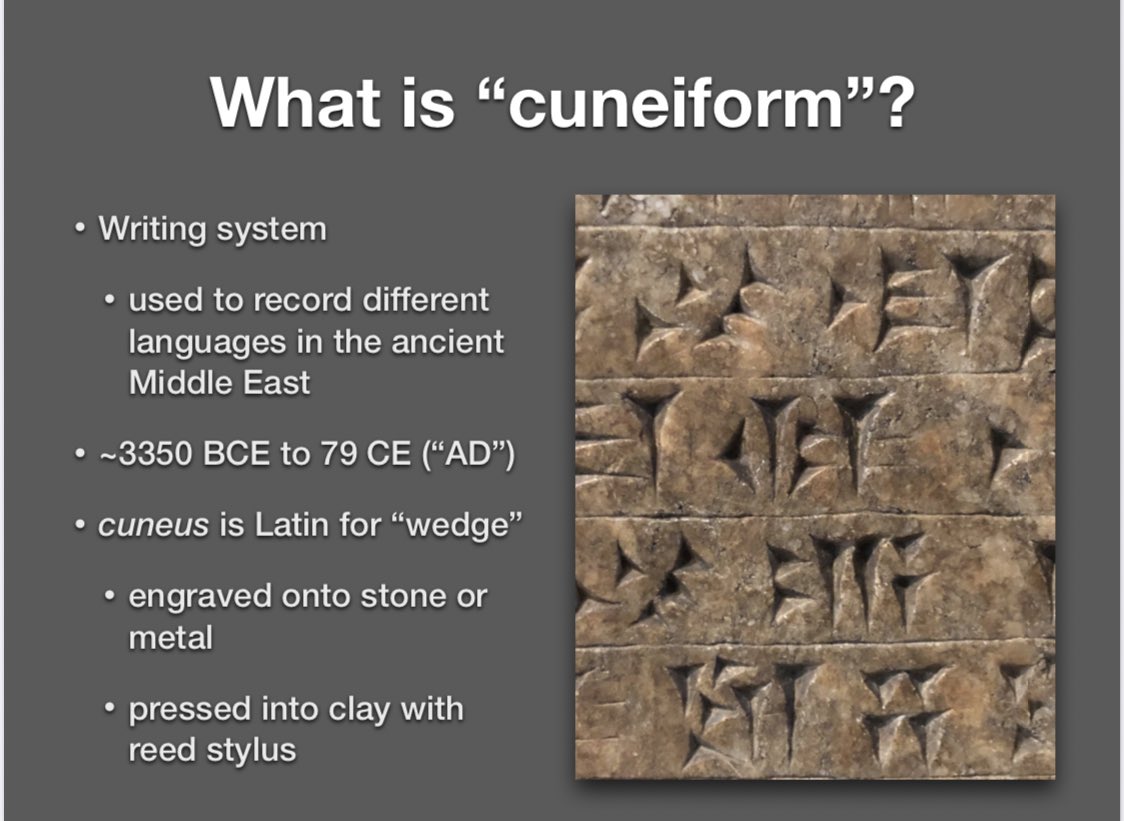

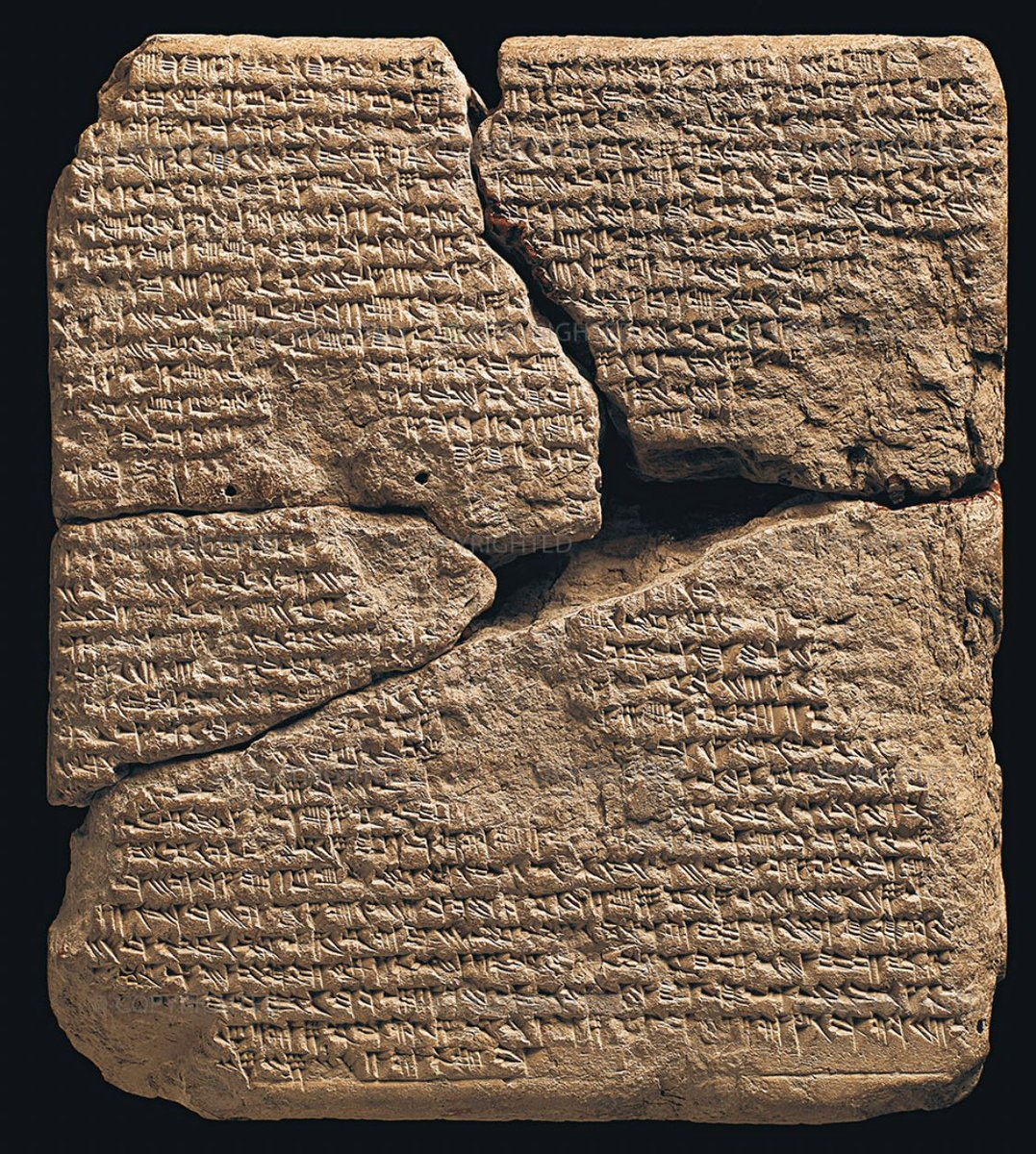

It’s impossible to talk about any aspect of scholarship in ancient Mesopotamia, like astronomy, without first defining Mesopotamia and introducing the writing system used there for around 3,000 years, cuneiform.

So let’s start.

So let’s start.

Mesopotamia is the region between and around the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers. It refers to an area—not a static, monolithic culture—in which civilisations rose and fell, whose boundaries expanded and contracted over hundreds of years.

Those civilisations had cuneiform in common.

Those civilisations had cuneiform in common.

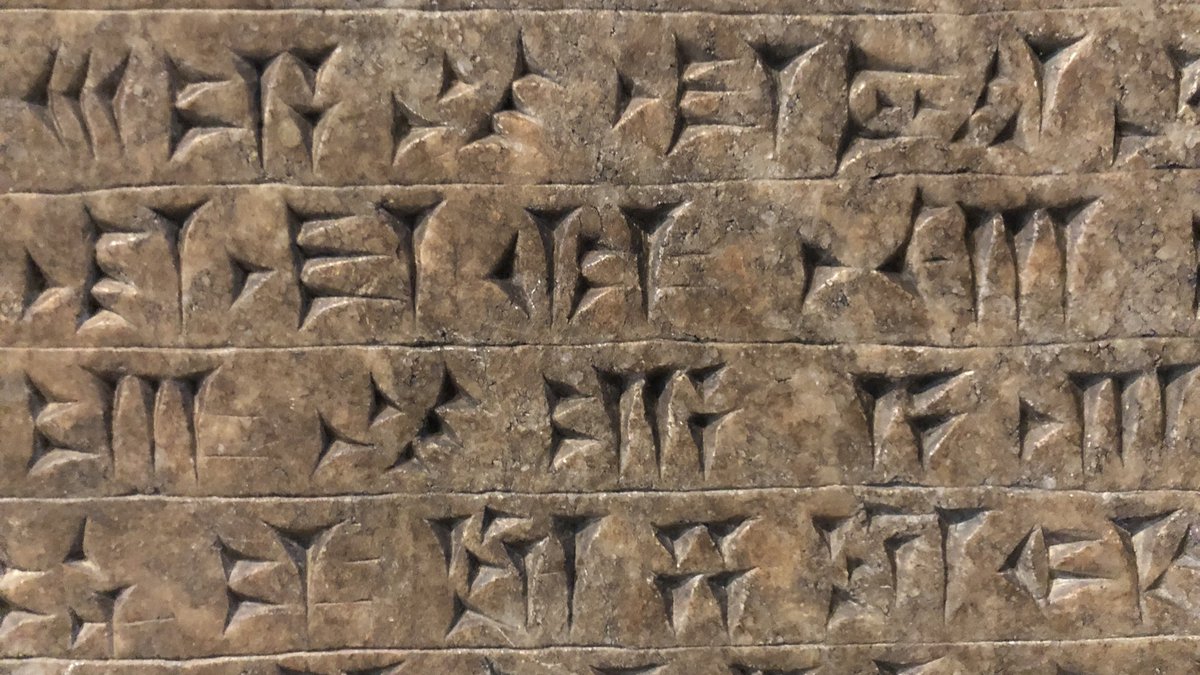

Cuneiform is a writing system (not a language) used to record various languages of the ancient Middle East. It gets its name from the Latin word cuneus, which means “wedge”.

It was initially developed to write Sumerian and later adapted to write Akkadian, Hittite, Ugaritic, etc

It was initially developed to write Sumerian and later adapted to write Akkadian, Hittite, Ugaritic, etc

(Btw, the fifth-graders at the school in Cameroon where I gave this Zoom lecture knew all this stuff already, which was pretty awesome.)

What was cuneiform used to record? Initially, economic transactions, but eventually, everything. Dictionaries, medical textbooks, poetry, letters, recipes, prayers, omens, laws, the list goes on...

Here’s a star map that shows the constellations on Jan 3-4, 650 BCE over Nineveh

Here’s a star map that shows the constellations on Jan 3-4, 650 BCE over Nineveh

This Neo-Assyrian map of the night sky over Nineveh on January 3-4, 650 BCE is quite a small tablet, as most cuneiform tablets are.

It shows the constellations, including drawings of Gemini and the Pleiades.

It shows the constellations, including drawings of Gemini and the Pleiades.

Before becoming an astronomer in ancient Assyria or Babylonia, you had to undergo extensive training, including basic scribal education, which varied from one period and place to another but shared some common denominators.

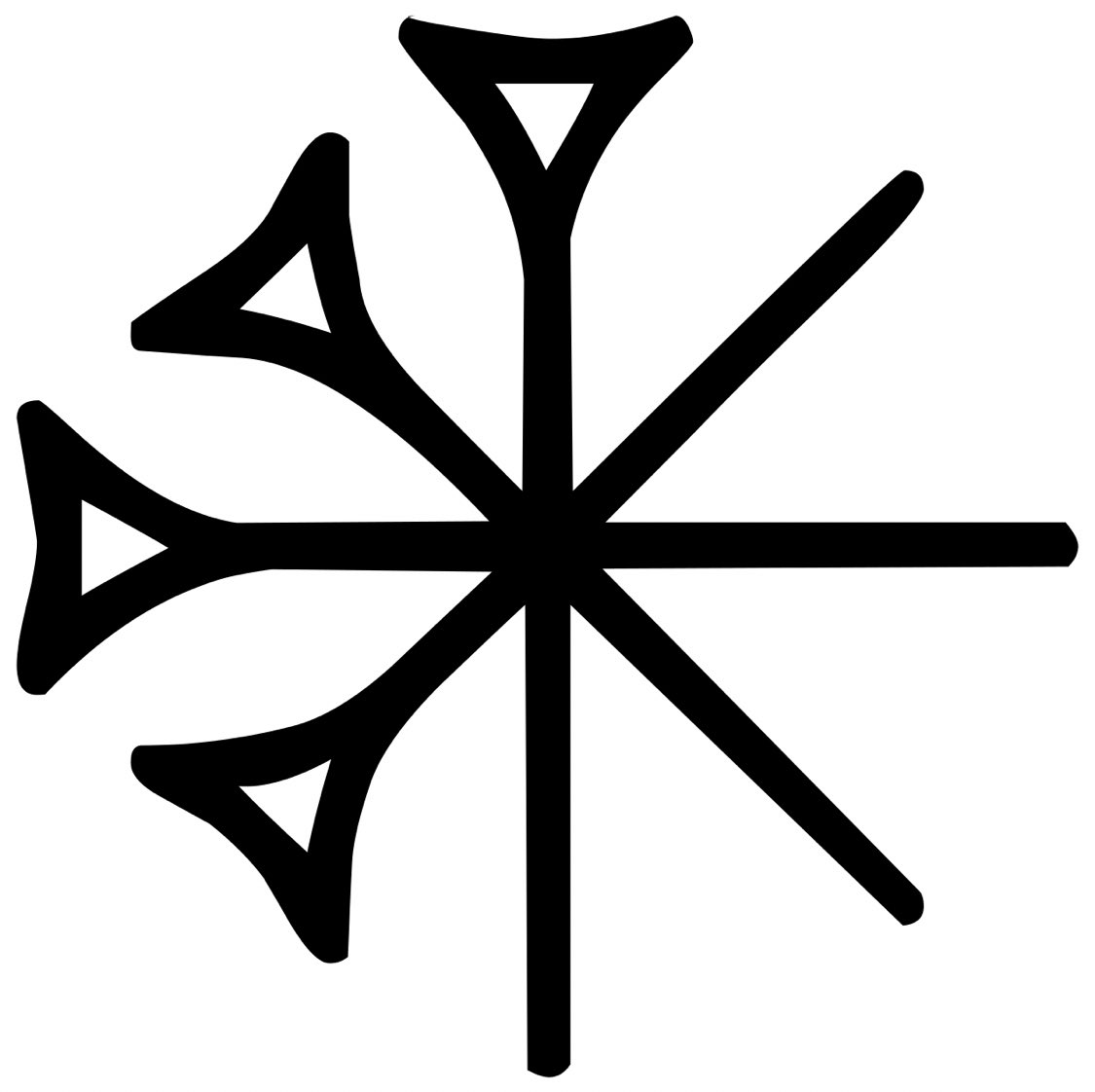

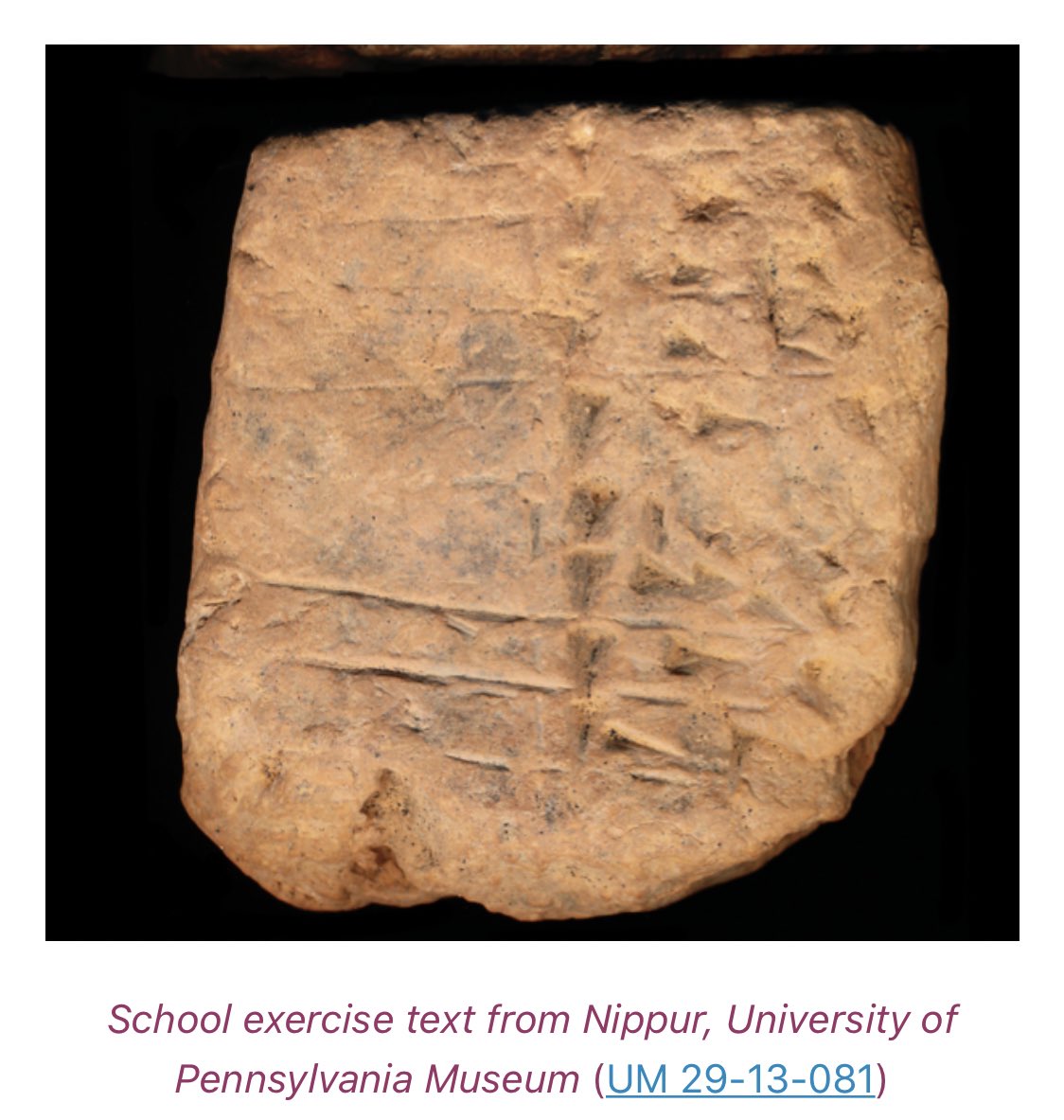

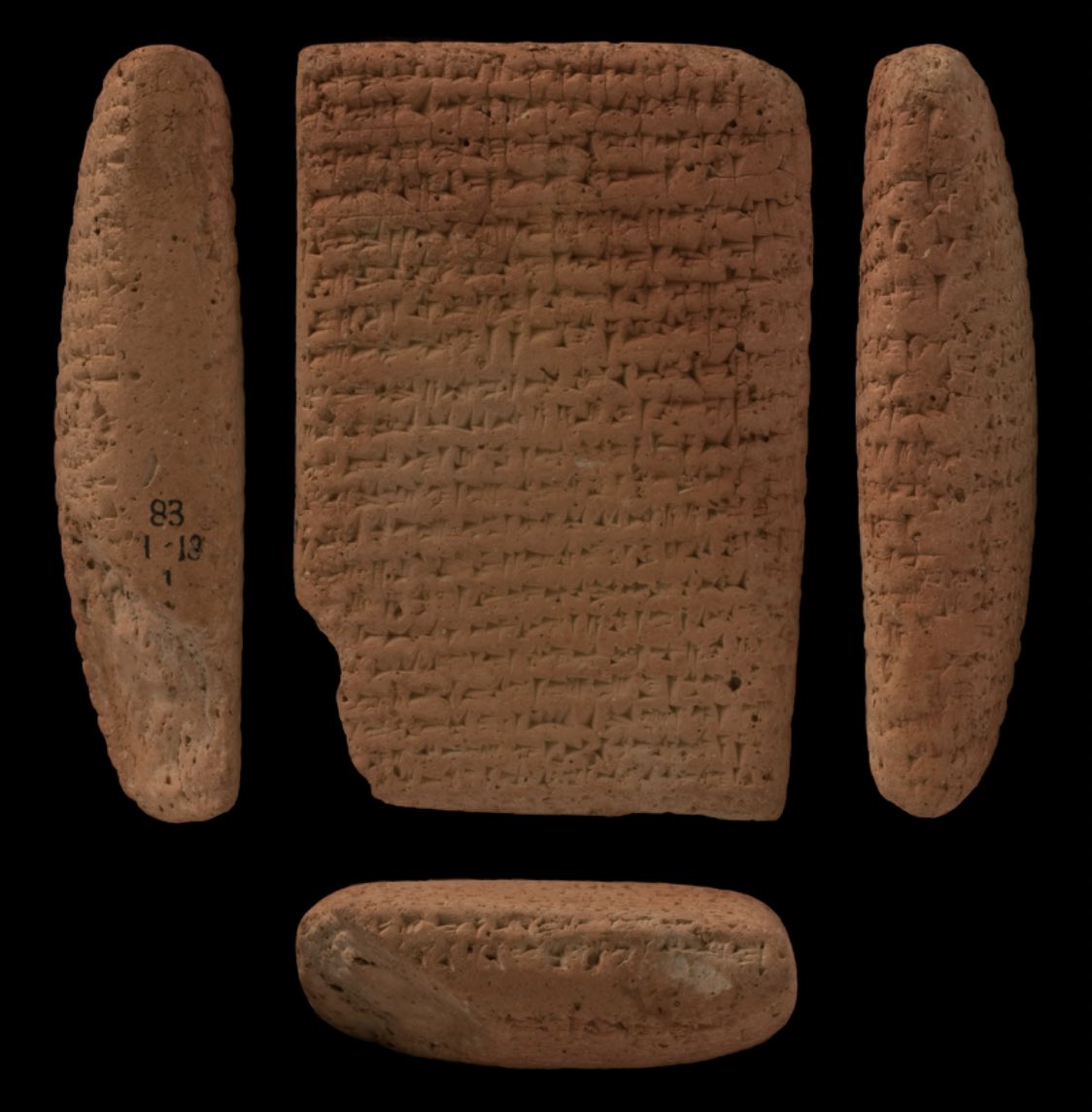

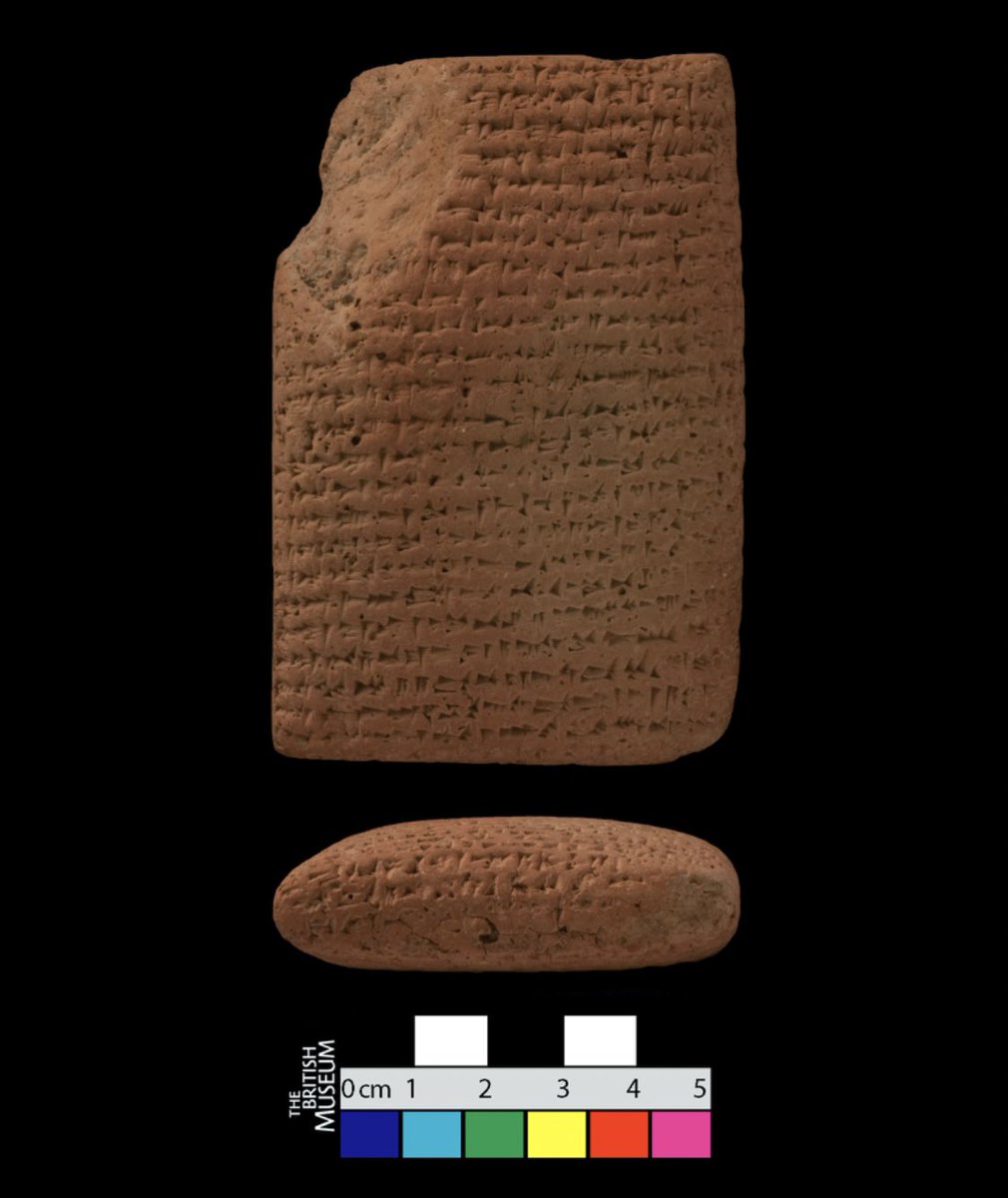

Students began by learning how to impress a basic wedge

Students began by learning how to impress a basic wedge

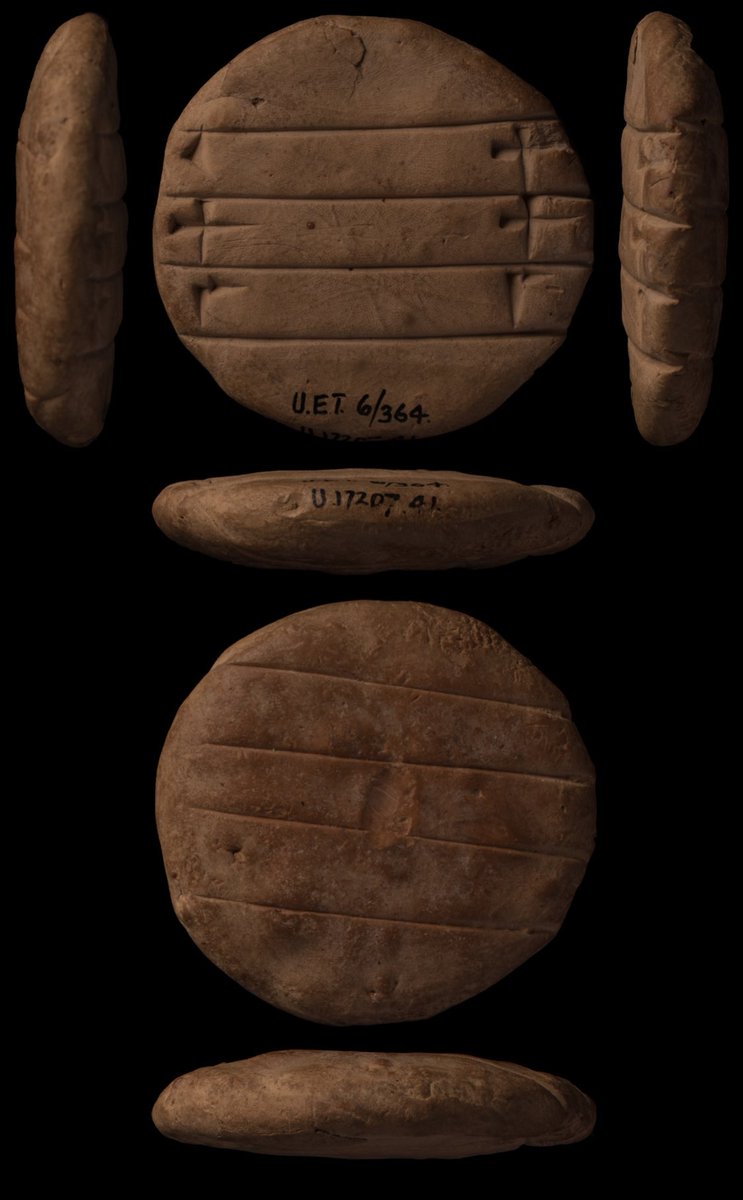

Yes, clay tablets made by young scribal students at schools in ancient Assyria and Babylonia are absolutely the most adorable thing ever, thank you for asking.

I mean, look at these things. One even has a doodle (maybe) of a fish. They are relatable and lovely.

I mean, look at these things. One even has a doodle (maybe) of a fish. They are relatable and lovely.

I wrote about Babylonian schools in this short post for @Papyrus_Stories

If you love ancient history, and learning about individuals and their lives, then you will love her blog #click=https://t.co/SAk9fUVwwN">https://papyrus-stories.com/2019/09/23/schoolboy-where-have-you-been-going-so-long-the-old-babylonian-student-and-school/amp/ #click=https://t.co/SAk9fUVwwN">https://papyrus-stories.com/2019/09/2...

If you love ancient history, and learning about individuals and their lives, then you will love her blog #click=https://t.co/SAk9fUVwwN">https://papyrus-stories.com/2019/09/23/schoolboy-where-have-you-been-going-so-long-the-old-babylonian-student-and-school/amp/ #click=https://t.co/SAk9fUVwwN">https://papyrus-stories.com/2019/09/2...

One important job of an astronomer/astrologer in ancient Mesopotamia was to observe phenomena in the sky to help make predictions about events on earth.

Natural phenomena were seen as messages from the gods about events to come. The stars were called the “heavenly writing”

Natural phenomena were seen as messages from the gods about events to come. The stars were called the “heavenly writing”

“If a star flashes like a torch from the east and sets in the west, the main army of the enemy will fall...the cavalry and professional troops should invade”

Astronomer Bēl-ušēzib advises the Neo-Assyrian king about battle tactics after observing a meteor http://oracc.iaas.upenn.edu/saao/saa10/P237234/html">https://oracc.iaas.upenn.edu/saao/saa1...

Astronomer Bēl-ušēzib advises the Neo-Assyrian king about battle tactics after observing a meteor http://oracc.iaas.upenn.edu/saao/saa10/P237234/html">https://oracc.iaas.upenn.edu/saao/saa1...

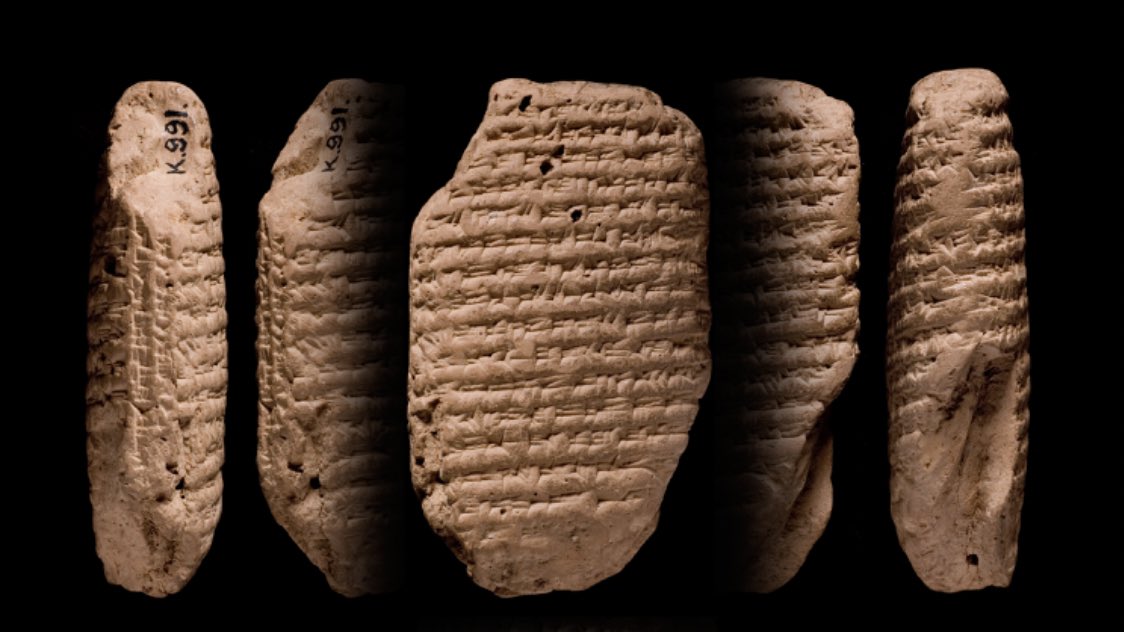

Astronomers in ancient Assyria also called each other out on their bullshit, in case you were wondering.

Balasî accuses another scholar who allegedly spotted Venus of being “in complete ignorance”.

“I repeat: he does not understand the difference between Mercury and Venus”

Balasî accuses another scholar who allegedly spotted Venus of being “in complete ignorance”.

“I repeat: he does not understand the difference between Mercury and Venus”

You can peruse for free many of these letters from astronomers (and other scholars, including physicians) to Neo-Assyrian kings via @opencuneiform

The letters are wonderful not just for their astronomical observations, but also for their humanity http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/saao/knpp/lettersqueriesandreports/index.html">https://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/saao/knpp...

The letters are wonderful not just for their astronomical observations, but also for their humanity http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/saao/knpp/lettersqueriesandreports/index.html">https://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/saao/knpp...

Around the same time that these letters were being written, a new type of astronomical text was created - the naṣāru ša ginê “regular watching”, or what we call Astronomical Diaries.

These record nightly observations of stuff in the sky and on earth. They are DETAILED

These record nightly observations of stuff in the sky and on earth. They are DETAILED

I’ve actually already done a whole ass thread on astronomy in ancient Mesopotamia, so you can learn more about Astronomical Diaries here https://twitter.com/moudhy/status/1153395621165973504?s=21">https://twitter.com/moudhy/st... https://twitter.com/moudhy/status/1153395621165973504">https://twitter.com/moudhy/st...

In the middle of the first millennium BCE, astronomers in ancient Babylonia developed the zodiac, which organised the ecliptic (the imaginary band the sun moves along) into 12 equal parts that roughly corresponded to where 12 constellations were.

These should sound familiar.

These should sound familiar.

māšu is the Akkadian word for “twin”, which was the name for the constellation, Gemini.

nēšu means “lion” and was the name for the constellation, Leo.

zuqaqīpu means “scorpion” and was the name for Scorpius.

suhurmāšu is a mythical goat-fish and was the name for Capricorn.

nēšu means “lion” and was the name for the constellation, Leo.

zuqaqīpu means “scorpion” and was the name for Scorpius.

suhurmāšu is a mythical goat-fish and was the name for Capricorn.

The zodiac made it easier to connect events in the sky with events in people’s lives. Birth astrology begins in Babylonia.

This tablet tells us that things will be “propitious” for the son of Sumu-usur, born on a night when Venus was in Taurus, Jupiter in Pisces, etc

This tablet tells us that things will be “propitious” for the son of Sumu-usur, born on a night when Venus was in Taurus, Jupiter in Pisces, etc

To make a very long, largely traceable story short, the zodiac, along with other elements of Babylonian astronomy (measurements, computational systems) survive into Greek and eventually modern astronomy.

Ancient Mesopotamia and cuneiform culture are still with us in many ways.

Ancient Mesopotamia and cuneiform culture are still with us in many ways.

There is a lot of misinformation out there about ancient Mesopotamia, and these tablets sometimes get used to discredit the very people who dedicated their lives to making them.

Lifetimes of curiosity, knowledge, and ingenuity went into cuneiform scholarship. Not aliens.

Lifetimes of curiosity, knowledge, and ingenuity went into cuneiform scholarship. Not aliens.

Anyway, that was the gist of the brief and hopefully accessible lecture I gave.

Hope you enjoyed the thread https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😊" title="Smiling face with smiling eyes" aria-label="Emoji: Smiling face with smiling eyes"> And if you’re really interested in this stuff, the people to follow are @IAStranger and @willismonroe

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😊" title="Smiling face with smiling eyes" aria-label="Emoji: Smiling face with smiling eyes"> And if you’re really interested in this stuff, the people to follow are @IAStranger and @willismonroe

Hope you enjoyed the thread

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter