This just out! A very exciting study on mice, led by @thomas_cucchi & Katerina Papyianni of @Le_Museum, in which I played a bit part (but I think an interesting one) 1/23 https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-64939-9">https://www.nature.com/articles/...

The backstory: we know that the ‘western’ house mouse (Mus musculus domesticus) started living in and around early sedentary settlements in the Levant c.15,000 years ago, thanks to work by @lweissbr: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1619137114">https://doi.org/10.1073/p... 2/23

And it spread with farming - reaching, for example, the famous Neolithic village of Çatalhöyük in central Turkey, where Emma Jenkins found it associated with grain storage c.9000-8500 years ago ( http://eprints.bournemouth.ac.uk/16331/ ;">https://eprints.bournemouth.ac.uk/16331/&qu... image Çatalhöyük Project, CC-BY-NC-SA). 3/23

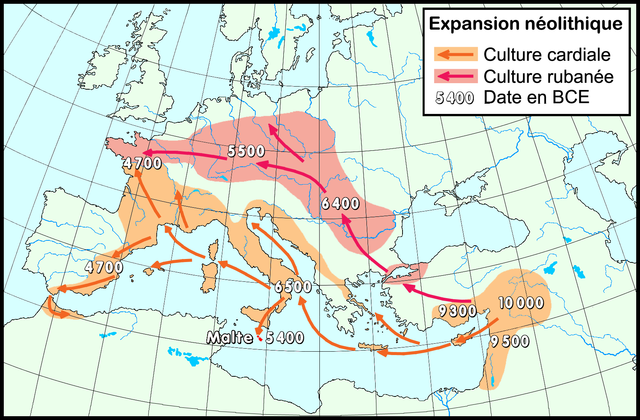

But while farming spread onwards in the following millennia - both around the Mediterranean coasts and up through the Balkans to central Europe - the mice, it seems, did not. 4/23

As @thomas_cucchi has shown previously, they didn’t reach the western Medditerranean or northwestern Europe until millennia later, in the Iron Age (i.e. first millennium BC) 5/23 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8312.2005.00445.x">https://doi.org/10.1111/j...

The new study looked at numerous mouse teeth from Greece, but found only wild mice (Mus macedonicus) at Neolithic sites. Even here (western) house mouse only appeared in the Bronze Age - 4000-5000 years later than the Çatalhöyük finds. 6/23

Why this long pause in dispersal? Presumably it has to do with settlements being large and dense enough to support mouse populations, as well as sufficiently connected to existing moused-infested areas for mice to spread and take hold. 7/23

Neolithic settlements in the Levant and Anatolia, such as Çatalhöyük, can be huge and densely built up, providing concentrations of food and shelter for mice. By contrast, early farming settlements in most of Europe were much smaller and more dispersed. 8/23

The colonisation of the Aegean by mice in the Bronze Age can be linked to the emergence of urbanism and complex exchange networks. Fair enough. But wait, were ALL European Neolithic settlements small and scattered? 9/23

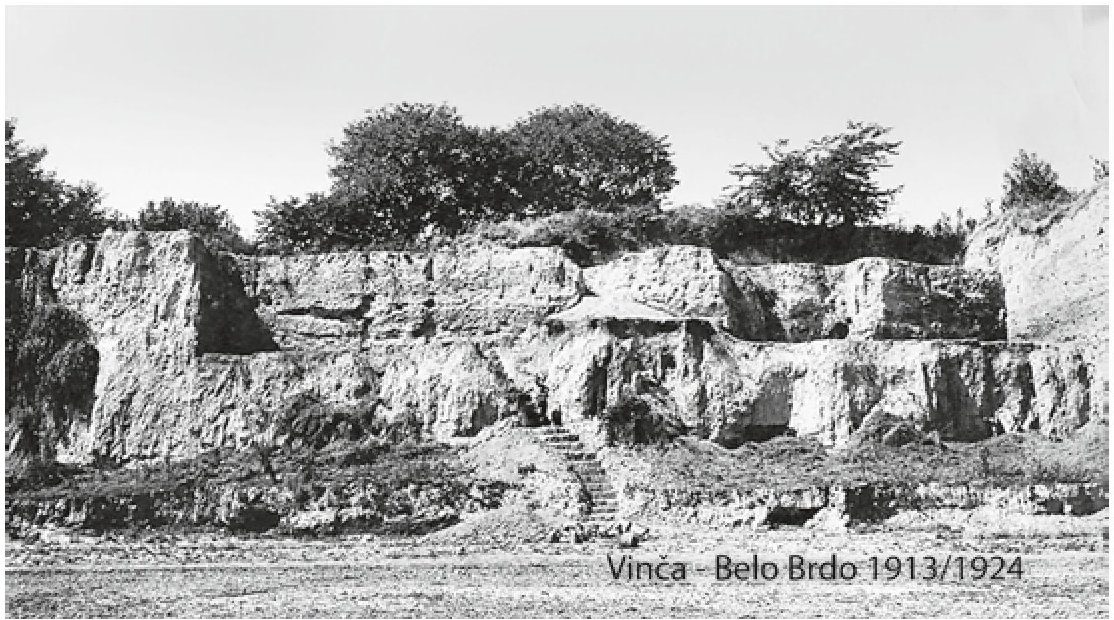

Certainly not. For example, I did my PhD on (larger) animals in the late Neolithic of Serbia, where large tell sites like Vinča supported human populations in the hundreds for centuries, with rows of daub houses and evidence for grain storage. 10/23

A few years ago, while reading about mice in @osteoconnor’s book, it occured to me that Vinča-period sites could surely have supported mice - yet none had been reported. Perhaps there was simply never a colonisation opportunity. 11/23

But since these sites have typically been excavated without much sieving, would we necessarily have found mice even if they were there? Well, archaeobotanists routinely run soil through fine meshes in search of plant remains - perhaps they find small bones too? 12/23

So I got in touch with an old friend, Dragana Filipović, who studies plant remains from Vinča. Yes, she told me, there are often small bones in her samples, which she sets aside in case anyone is interested. 13/23

We took a trip out to the on-site store one Sunday afternoon (it& #39;s just outside Belgrade), looked through a few sample bags, and there they were: alongside lots of tiny fish bones, quite a few rodent remains. 14/23

These included some burnt mandibles that looked a lot like house mouse. We sent them off to Katerina in Paris, who was able to confirm them not just as Mus musculus, but as the EASTERN subspecies, M. m. musculus (picture credit to Kitty Locker). 15/23

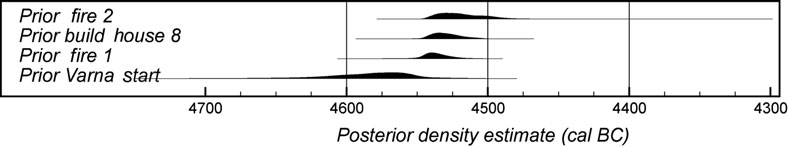

These burnt bones came from the floor layer of a house destroyed by fire, sealed by burnt daub rubble. By sheer good fortune, the date of this fire can be pinpointed to 6510-6460 BP (“fire 1” below) 16/23 https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2015.101(image:">https://doi.org/10.15184/... Philosophy Faculty, Belgrade)

How? That’s another story, but it’s thanks to a super-intensive radiocarbon dating programme by the Vinča team with Alex Bayliss and Alasdair Whittle. Worth a read. 17/23

That makes these the earliest known house mice in Europe, earlier even than some Chalcolithic finds from Romania (also the eastern subspecies), previously published by Thomas & colleagues. 18/23 https://doi.org/10.1177/0959683611405233">https://doi.org/10.1177/0...

But how did they get here? Presumably not with the main spread of farming from the south, since they pre-date Greek house mice, and are the wrong subspecies. 19/23

We can’t rule out spread around the southern shores of the Black Sea and across the Bosphorus, as we haven’t sampled these areas. But perhaps more likely they spread around the north of the Black Sea. How? When? Why? 20/23

That remains to be seen, but the emergence of large, dense Late Neolithic/Chalcolithic settlements from the central Balkans upto Ukraine may have provided a colonisation opportunity for M. m. musculus long before its ‘western’ cousin spread west. 21/23

The moral of the story? Sometimes you need to go looking for the unexpected. Where else might we find unreported mice sitting in sample bags, to rewrite the story again? Oh, and zooarchaeologists should talk to archaeobotanists more. 22/23

A final interesting point: this division between the eastern and western subspecies persists to this day, with a border (ok, hybridization zone) splitting Europe in half from Denmark to the Black Sea. 23/23

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01222.x">https://doi.org/10.1111/j...

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01222.x">https://doi.org/10.1111/j...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter