I just posted the camera-ready version of our upcoming PETS paper here: https://blues.cs.berkeley.edu/blog/2020/03/25/the-price-is-not-right-comparing-privacy-in-free-and-paid-apps-pets-20/

The">https://blues.cs.berkeley.edu/blog/2020... Price is (Not) Right: Comparing Privacy in Free and Paid Apps. Proceedings on Privacy Enhancing Technologies (PoPETS), 2020(3).

The">https://blues.cs.berkeley.edu/blog/2020... Price is (Not) Right: Comparing Privacy in Free and Paid Apps. Proceedings on Privacy Enhancing Technologies (PoPETS), 2020(3).

This effort was largely led by undergraduate @catherinekshan who will be starting her PhD at Stanford in the fall!

(As well as @irwinreyescom, @AlvaroFeal, Joel Reardon, @primalw, @narseo, @AmitElazari, and @kenbamberger)

(As well as @irwinreyescom, @AlvaroFeal, Joel Reardon, @primalw, @narseo, @AmitElazari, and @kenbamberger)

We examined the privacy differences between apps that offer both "free" and premium "ad-free" versions. That is, when consumers pay for "ad-free" versions of apps, do they get better privacy protections?

Moreover, do they *think* that they& #39;re getting better privacy protections?

Moreover, do they *think* that they& #39;re getting better privacy protections?

The reason why we chose to look at this is that it& #39;s been uncritically reported that if consumers wish to have better privacy, they can simply elect to pay for their services.

Exhibit A: https://fortune.com/2018/04/07/sheryl-sandberg-says-facebook-users-would-have-to-pay-for-total-privacy/

So">https://fortune.com/2018/04/0... our research question is, can consumers simply pay for privacy?

Exhibit A: https://fortune.com/2018/04/07/sheryl-sandberg-says-facebook-users-would-have-to-pay-for-total-privacy/

So">https://fortune.com/2018/04/0... our research question is, can consumers simply pay for privacy?

We decided to answer this in two parts: first by studying the privacy differences, if any, afforded by paid apps, and then by examining consumer expectations of what they think they& #39;re getting from paid apps.

First, we used crowdsourcing to identify 5,877 apps that offer both free and paid versions.

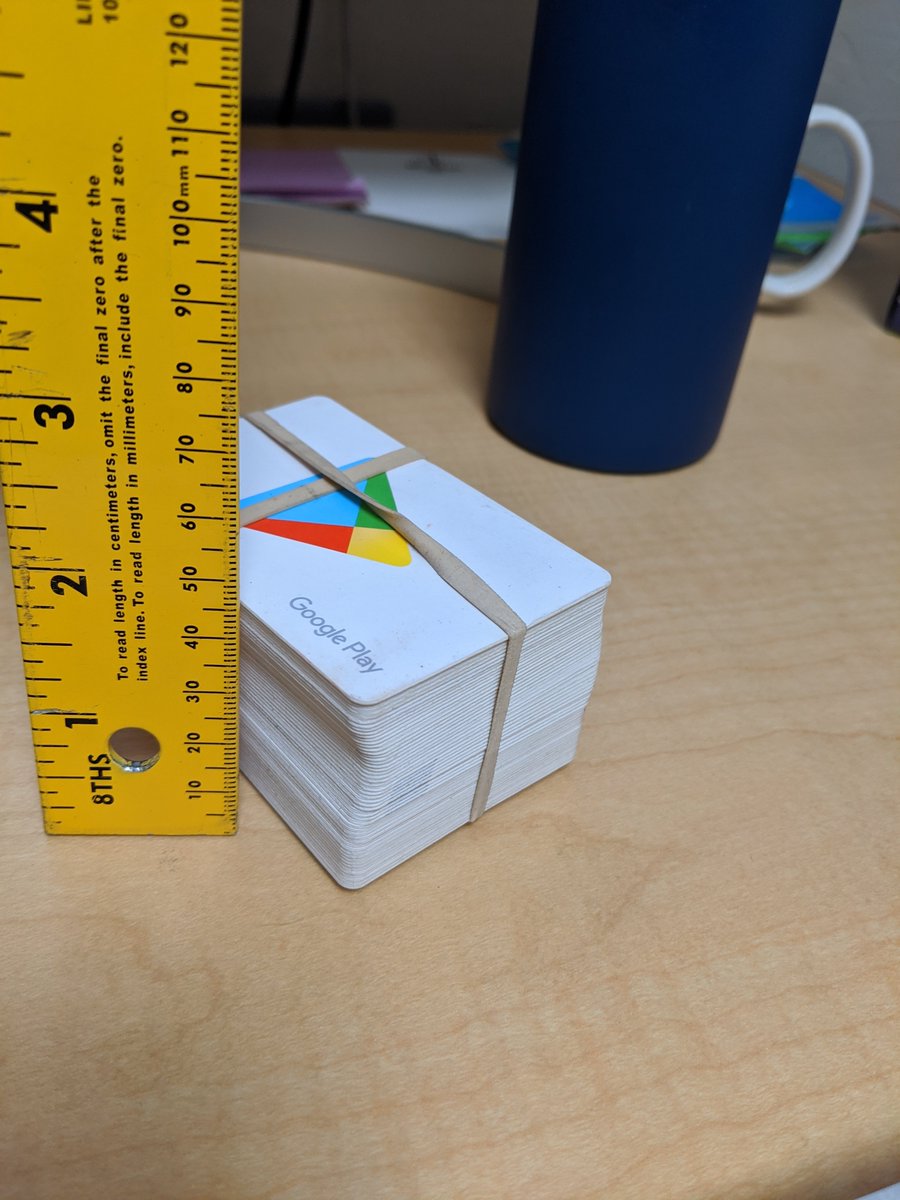

Next, we purchased all of the paid versions. This was no easy process, as I documented when we first started:

https://twitter.com/v0max/status/1076927245107777536

Here& #39;s">https://twitter.com/v0max/sta... a picture of the gift cards I needed to buy.

Next, we purchased all of the paid versions. This was no easy process, as I documented when we first started:

https://twitter.com/v0max/status/1076927245107777536

Here& #39;s">https://twitter.com/v0max/sta... a picture of the gift cards I needed to buy.

Next, we fed all of these apps to the @AppCensusInc testbed, which ran both the free and paid versions of the same app, side-by-side with the same input.

We monitored (a) the permissions accessed, (b) the third-party SDKs present, and (c) transmissions of personal data.

We monitored (a) the permissions accessed, (b) the third-party SDKs present, and (c) transmissions of personal data.

We found that 74% of the paid apps requested exactly the same set of dangerous permissions ( #dangerous_permissions">https://developer.android.com/guide/topics/permissions/overview #dangerous_permissions)">https://developer.android.com/guide/top... as their free versions.

Similarly, 45% of the paid apps bundled exactly the same set of third-party SDKs as their free counterparts.

Similarly, 45% of the paid apps bundled exactly the same set of third-party SDKs as their free counterparts.

When running the apps, we observed that 32% of the time, the paid app transmitted exactly the same personal information to exactly the same third parties as its free counterpart.

That is, for a third of the apps, consumers do not get better privacy when they pay for their apps.

That is, for a third of the apps, consumers do not get better privacy when they pay for their apps.

In many apps, the "ad free" version doesn& #39;t display ads, which is expected.

However, what is unexpected is that it still collects the exact same personal information so that behavioral advertising can be performed in *other* apps and services.

However, what is unexpected is that it still collects the exact same personal information so that behavioral advertising can be performed in *other* apps and services.

Worse, we observe that there is no way of determining when paying for an app is likely to yield better privacy and when it is not: in 3.7% of the privacy policies that we were able to find, they indicated different practices for the paid vs. free versions.

Of course, for 40% of the apps, there simply wasn& #39;t a working privacy policy link in the Play Store. So really, only about 2% of the paid apps had different policies.

This all begs the followup question: what do consumers *think* they& #39;re getting when they pay for apps?

This all begs the followup question: what do consumers *think* they& #39;re getting when they pay for apps?

We answered this by conducting an online survey (n=998) of consumer app-buying expectations.

When we asked an open-ended question about what consumers would receive when purchasing an app that has a free version, 86% mentioned no ads.

But is this synonymous with privacy?

When we asked an open-ended question about what consumers would receive when purchasing an app that has a free version, 86% mentioned no ads.

But is this synonymous with privacy?

They said that paid apps would be *less* likely to share data with third parties (including advertisers), use it for secondary purposes, or access more data than needed.

They said paid apps are *more* likely to offer effective privacy controls and delete data when not needed.

They said paid apps are *more* likely to offer effective privacy controls and delete data when not needed.

The point of all of this is that many consumers are of the belief that "ad-free" and "premium" versions of free apps provide them with better privacy protections, but in reality, this is simply not the case.

(On the plus side, I guess this means privacy isn& #39;t a luxury good...)

(On the plus side, I guess this means privacy isn& #39;t a luxury good...)

Worse, there& #39;s no way for consumers to know when they are receiving better privacy by electing to pay: for 98% of the apps, the privacy policies didn& #39;t differentiate between an app& #39;s free and paid versions.

Consumers don& #39;t have the tools to figure this out on their own.

Consumers don& #39;t have the tools to figure this out on their own.

Separately, we have a forthcoming law review article that discusses many of these issues from a consumer protection standpoint and why this matters for public policy:

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3464667">https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/pape...

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3464667">https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/pape...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter