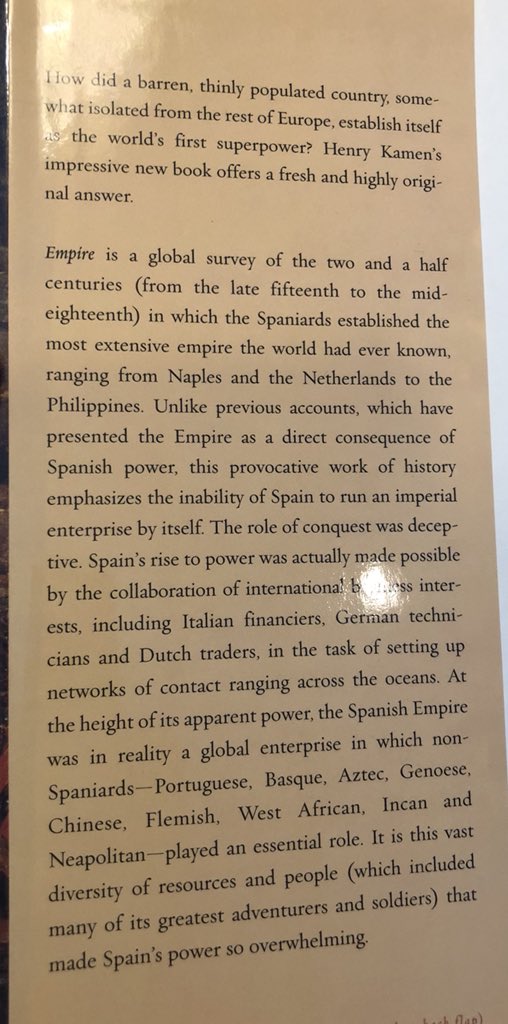

Going to continue down the rabbit hole of the paradoxes, contradictions, and ironies of Spanish rule...

“The case of Spain under the Habsburgs is the fullest and clearest example of the imposition of foreign, international capital and capitalists on the government.”

Innovations in systemic governance during the reign of Charles:

(1) linking of an unprecedentedly global regime to modern mobile capital

(2) the institutionalization of a far reaching postal network.

(3) The use of the state as a way of spreading business risks for traders and financiers.

Charles V did not tend to think in terms of a grandiose theory of empire. Some of his advisors did, but curiously they didn’t think the American territories were part of this conception.

The French defeat at battle of Pavia was the first notable demonstration of the Spanish as a competive military force in early modern Europe, but it should be remembered that most of the Imperial forces there were Germans and Italians.

“There would have been no Spanish empire without Italy.”

Intermarriage between Italian and Spanish nobles created an established caste of soldiers and administrators.

Northern Italian banking houses controlled the trade of the Iberian peninsula, and in turn put their considerable financial resources at the service of the Spanish monarchy.

Hapsburg domainance in the Western Mediterranean relied heavily on Italian naval and military dominance.

“As the Spanish were conquering the Americas, the Genoese found their America in Spain.”

One could conceptualize the conquest of the Americas as the last and most enduring hurrah of the Mediterranean world-system.

The Netherlands and Spain were closely tied by trade since the Middle Ages.

The Netherlands remained a beloved homeland of Charles V throughout his life.

Down to the 1550s, outside certain Italian circles, there was no widespread anti-Spanish feeling in Europe.

Las Casas notes an incident in which he asked a Spanish father why he was sending his sons to the Americas. He was told it was in order that they could “live in a free world.”

The Weslers, a German banking house, sponsored the early colonization of Venezuela.

The sugar mills of Hispaniola were mainly financed by the Genoese.

The destruction of the Arawaks through cruelty and overwork prepared the way for the initial demand of African slaves.

The historian Oviedo says of Balboa’s famous trek: “the cruelties were not stated, but they were many.”

Notably though there was no resistance to the explorer on his journey, and much co-operation by local tribes.

Charles V gave key industries of Spain’s economy to foreign financiers to pay off his massive debts.

There were signs of early English animosity towards the Spanish during the visit of then prince Phillip the island, though the royal heir was himself apparently well liked.

“Philip’s empire, the Elizabethan chronicler William Camden later recognized, ‘extended so farre and wide, above all emperors before him, that he might truly say, Sol mihi semper lucet, the sunne always shineth upon me.’”

Private enterprise, not state action, was the primary motor of Spanish expansion in the early colonial period.

Bands of adventurers staked claims and created facts on the ground which the crown then sought to bring under control.

The *feudal* concept of the encomienda contract created a necessary link between the actions of the explorers and conquerers on the frontier and the European homeland.

The conquest of the Americas was never completed by the Spanish, even in areas under their nominal control.

What they in fact governed was mainly the fertile areas of the Caribbean and the Pacific

The Spanish conquistadors were neither the dregs of society nor hidalgos.

85% of the Spanish who conquered Tenochtitlan could sign their names, which suggests literacy.

We only know of the original profession of 13% of this same group of Spaniards but it also suggests a similar mean between the gentry and the lumpen: scribes, artisans, professional soldiers, and sailors.

Regardless of their origins, most ended their days in poverty.

The capture of Atahualpa did involve one causality on the Spanish side: An unidentified black man.

The killing of Atahualpa was treated as a crime by later Spanish commentators.

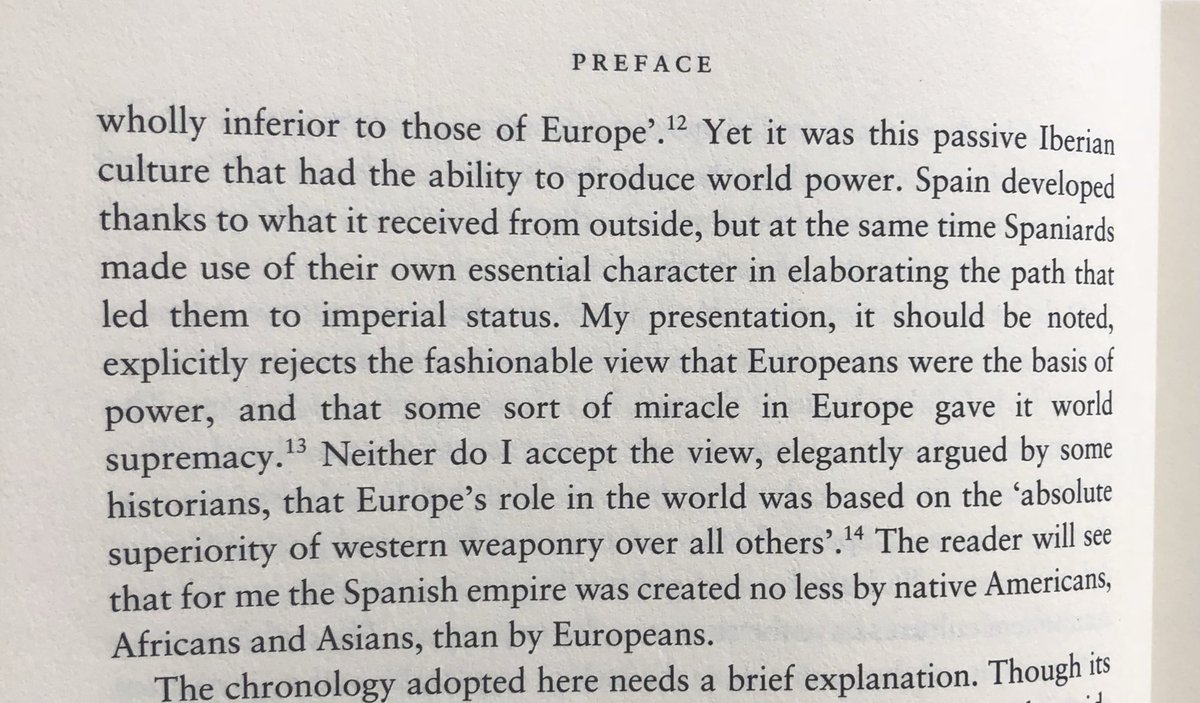

The protracted destruction of the Incan empire, like that of the Aztec, would not have taken place without large scale indigenous support for the Spanish.

Kamen lists three factors explaining Spanish success in the Americas in the 1500s:

1. Effectively playing to the supernatural symbols of the indigenous peoples.

2. Superior naval mobility.

3. And, most importantly of all, gaining the support and co-operation of native peoples.

Notably, Tlaxcalan lords allied to the Spanish enjoyed the right to title themselves “conquistadors.”

There were many peoples in the Americas that were never conquered by the Spanish, pace the impression given by maps.

The Spanish didn’t think it important to control them, and they didn’t go out of their way to resist the Europeans.

To make my own observation: it seems that being radically unentabgled in existing indigenous power relations was more important for the Spanish than guns or horses.

It was this distance from the American environment that enabled various native peoples to view the conquistadores as allies against local hegemons or traditional rivals.

The real courage, or, from another perspective, hubris, of the Spanish conquerers overtime became a legend about the exceptional racial character of Castilians, editing out the necessity of indigenous allies in the actual history.

Not to mention the cast of other Europeans who participated in the story.

“In the strange Europeon way of thinking, simply to be there confirmed possession of those territories.”

Relative to the size of the vast territories of the Americas, the Spanish were a highly vulnerable and almost invisible presence.

Instead of creating radically new systems, the Spanish tended to insert themselves at the top of pre-existing structures of indigenous governance, taking the place of the native empires they had defeated.

The mining industry was a major exception to this role.

Jurist Tomas Lopez Medel in 1542 on the need for the New Laws of the Indies for the Good Treatment and Preservation of the Indians, having visited Guatamala himself.

Again, however, the Spanish, despite their capacity cruelty, were never numerous or powerful enough to be in a position to exterminate the indigenous population, even if they had wanted to kill off their source of labour. Pestilence was undoubtably the biggest killer.

“The epidemics....often preceded contact with the invaders, whose pathogens were carried in advance of their arrival, by the air, by insects, by animals, and by natives.”

One Spanish settler bluntly said that to be poor (and European) in the New World was better than the home country because you were always in charge and didn’t have to work personally (because of nonwhite labour).

The biggest stream of people from the Old World to the New during this period was the Atlantic slave trade.

This trade was conducted in the hands of private entrepreneurs with money advanced by the state.

Which fits the earlier described pattern of imperial reliance on non-state actors.

The trade in human beings linked Europeon commercial networks with pre-existing systems of internal African slavery, similar to how American indigenous tribal structures mediated the encomienda units.

There was an upsurge of criticisms of the slave trade by Spanish officialdom and ecclesiastical authorities in the early colonial period that were severe enough to convince Phillip II to temporarily suspend the license of the Portuguese merchants who dominated the trafficking.

A notable figure of this anti-slavery movement was friar Tomas de Mercado, a Dominican like Las Casas. He reported that 4/5ths of the blacks transported died en route.

Another notable abolitionist figure was the Jesuit Alonso de Sandoval, who wrote on the Salvation of the Africans, bitterly criticizing the Middle Passage.

“Slavery is the beginning of all offenses and travails, it is a perpetual death, a living death in which people die even while they are alive.”

-Sandoval

-Sandoval

Blacks soon outnumbered whites in the New World because of slavery.

It was not merely as unfree laborer that Africans participated in empire, however.

“Blacks were with Balboa when he claimed the Pacific, with Pedrarias Davila when he colonized Panama, with Cortez when he marched to Tenochtitlan, with Alvarado when he entered Guatemala.”

Jean Valiente was perhaps the most successful and famous of the African conquistadors.

*Juan

Because of the lack of European soldiers, Blacks were the main element of the Spanish militias that dealt with rebels, Indians, pirates, and rival colonial powers.

“Blacks...were an uprooted people, and showed an amazing ability to blend into their host societies.”

“In no small measure, the black man created the empire that Spain directed in the New World.”

This was historically not recognized by Spanish historians, in notable contrast to the attitude of their Portuguese counterparts towards the African element of the Brazilian colonial project.

The Catholic missionaries to the New World were guided by sometimes complementary, sometime contradictory ideological and strategic imperatives.

They worked in conjunction with the Spanish empire, but the religious culture many wanted to spread was not that of the Iberian peninsula.

These clerics were highly influenced by the Devotio Moderna and, in the case of the Dominicans, the revival of Thomas Aquinas, not so much by a specifically Castilian tradition.

These priests and brothers wanted to spread a renewed Church that would by pass the corruption, inadequate catechesis, and divisions of Europeon Christendom.

Another factor was the prevalence of apocalyptic beliefs that the preaching of the Gospel to the newly discovered peoples would precede the second Coming.

Another factor was a proto-anthropological fascination with indigenous culture.

History of the Things of New Spain or Florentine Codex, was a product of the Fransican Sahagun and Nahua aides. It contains one the first authentic accounts of the initial contact between Spaniards and the indigenous.

Phillip II was fascinated with research into the American civilization. Despite this, a sudden and unexplained Royal suspension of such work occurred in 1577. Happily, it only really affected the Franciscan order.

https://twitter.com/redmaistre/status/1263994606791921665?s=21">https://twitter.com/redmaistr... https://twitter.com/redmaistre/status/1263994606791921665">https://twitter.com/redmaistr...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter