I want to spend June tweeting about Chinami Kondo, beginning with translating excerpts from 捨て石理め草 on twitter. I can& #39;t believe it will soon be 10 years since her sudden passing. I hope other people will join me and post about her a lot!

#閑不徹

#近藤千浪

@IrregularRhythm

#閑不徹

#近藤千浪

@IrregularRhythm

Thanks to @IrregularRhythm, Red Eye, and @Justseeds we have this awesome poster celebrating Sekirankai and a heartfelt tribute to Chinami Kondo.

"Her quietly marching figure was beautiful to behold."

#近藤千浪 #近藤文庫 #赤瀾会

https://justseeds.org/celebrate-peoples-history-1-seki-ran-kai/">https://justseeds.org/celebrate...

"Her quietly marching figure was beautiful to behold."

#近藤千浪 #近藤文庫 #赤瀾会

https://justseeds.org/celebrate-peoples-history-1-seki-ran-kai/">https://justseeds.org/celebrate...

Chinami Kondo probably played an important role in you being able to learn whatever you’ve learned about the history of anarchism in Japan. She was the caretaker of precious objects and texts that 3 generations of anarchists endeavored to safeguard for future generations.

Chinami was also the caretaker of many anarchist and feminist relationships and stories. She was a 3rd generation radical. Her grandfather was Toshihiko Sakai, co-founder of the Heiminsha (Commoners’ Society) & the Heimin Shinbun (The Commoners’ Paper).

His daughter Magara, Chinami’s mother, played a central role in the anti-capitalist & feminist group Sekirankai (Red Wave Society). Chinami’s father, Kenji Kondo, was chief secretary of the Japan Anarchist Federation.

Throughout June I’ll tweet about Chinami. June 20th will be the 10th anniversary of her passing, which came too suddenly and too soon. I hope others will tweet about her too!

Chinami’s partner Seisho Shirani edited a memorial volume of some of Chinami’s writings titled 捨て石埋め草 (Suteishi umekusa). I’ll write about that title later. I want to start by translating a passage from page 51:

Leaving aside the year, I was born on September 1st. My father’s friends and acquaintances would often say it was “bad karma” for Kenji Kondo’s daughter to be born on September 1st.

I learned the words “bad karma” without understanding what they meant, and I thought I was a “bad karma” girl. Though I was a child, I could at least understand that I was born on a bad day through the pained expressions on the faces of my father’s friends.

[On September 1, 1923, Taisho 12, the day of the Great Kanto Earthquake] my grandfather Toshihiko Sakai and mother Magara Sakai (not yet married) were in prison.

Grandfather had been in the Ichigaya prison since June because he was involved in the First Communist Party Incident, and Mother had been in since July for violating the law prohibiting the publication of antiwar propaganda.

My father Kenji Kondo and other Labor Union Council comrades were detained in the Komagome police station in so-called “protective custody.” My grandfather and parents thus spent the earthquake and subsequent days of social turmoil under the “protection” of the authorities.

Furthermore, they learned of the terrible deaths of Osugi, Noe, and Munekazu while they were in prison.

[end quotation]

[end quotation]

Here’s how the late Mikiso Hane (who credited Chinami in his acknowledgments) describes it on pages 130-131 in his book Reflections on the Way to the Gallows: Rebel Women in PreWar Japan:

“In July 1922 the Communist party was organized illegally under the leadership of Magara’s father, Sakai Toshihiko… the authorities discovered the existence of the Communist party and arrested its leaders, including Magara’s father.

As a result, both Magara and her father were in prison during the Great Earthquake of 1923, and unlike many of their fellow socialists and communists, were not victims of the right-wing and military lynchers and assassins.”

Chinami continues:

Grandfather was released from prison on bail in December of that year, and Mother was released in November. My father got out of jail on October 3rd and met Kyutaro Wada, who was set free from custody for only one night due to illness.

Grandfather was released from prison on bail in December of that year, and Mother was released in November. My father got out of jail on October 3rd and met Kyutaro Wada, who was set free from custody for only one night due to illness.

My father wrote about these events at the time in his book Recollections of an Anarchist:

‘We decided to send you off alone tomorrow morning. I guess you don’t know about it yet, but it’s been decided that you will take Osugi’s children to Noe’s parents’ house in Fukuoka.’

‘We decided to send you off alone tomorrow morning. I guess you don’t know about it yet, but it’s been decided that you will take Osugi’s children to Noe’s parents’ house in Fukuoka.’

Wada stood there, staring at me. I replied, ‘I see’, but actually I did not understand anything. Only once I put my feeling of foreboding together with Wada’s words did I understand there could only be one reason for all this.

Wada was headed back to jail and asked for everyone to get together because there was news to share, and we all formed a circle.

I barely got out the words ‘Now that Wada is here…’ when Katsura Mochizuki said, ‘I think Osugi was probably killed’. For the next 10 days we both thought about that same thing. And we weren’t able to discuss it with each other.”

From that day my father coped first with the funerals of Osugi, Noe, and Munekazu, then many ensuing incidents and the deaths of many other comrades.

As for my grandfather, he wrote about his reaction to Osugi’s death as follows:

“It felt like an awful blow, as if someone suddenly attacked me from behind and bashed my head over and over with a wooden club…

“It felt like an awful blow, as if someone suddenly attacked me from behind and bashed my head over and over with a wooden club…

We can think of us all as connected, as directly or indirectly joined flesh….

The death of one of the most powerful figures in the Labor Movement was like having a chunk of our own flesh cut out….

My feeling of connection with Osugi as if joined flesh deepened …

The death of one of the most powerful figures in the Labor Movement was like having a chunk of our own flesh cut out….

My feeling of connection with Osugi as if joined flesh deepened …

To wit, what was done to Osugi was done to me. One part of my body was killed. I felt like one of the corpses I saw around in the darkness was my own.”

[The History of the Socialist Movement in Japan, Chuokoron, vol 46, no. 6, June, 1931]

[The History of the Socialist Movement in Japan, Chuokoron, vol 46, no. 6, June, 1931]

Mother wrote about being imprisoned during and after the earthquake too:

“Although in Tokyo, I didn’t understand what was happening, and I still want to say that September is the ‘month of bitterness’, the month of painful things.”

[Tokyo Shimbun, 9/4/1973, evening edition]

“Although in Tokyo, I didn’t understand what was happening, and I still want to say that September is the ‘month of bitterness’, the month of painful things.”

[Tokyo Shimbun, 9/4/1973, evening edition]

[end quotation]

The Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 wasn& #39;t the 1st time Chinami& #39;s grandfather was in prison while comrades faced even greater repression and oppression, including execution. Toshihiko Sakai was already in prison when the High Treason Incident happened too.

The Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 wasn& #39;t the 1st time Chinami& #39;s grandfather was in prison while comrades faced even greater repression and oppression, including execution. Toshihiko Sakai was already in prison when the High Treason Incident happened too.

12 years before Ito, Osugi, & Munekazu were murdered, Kanno, Uchiyama, Kotoku, & 9 other anarchists were executed because they wanted the emperor system to be abolished. Sakai was already in prison.

On page 57, Chinami writes about this too:

On page 57, Chinami writes about this too:

Grandfather was sent to the Chiba Prison in 1908 (Meiji 41) because of the Red Flag Incident, and he was locked up there for two years. He was released in September of 1910.

He avoided being implicated in the High Treason Incident because he was imprisoned.

[end quotation]

[end quotation]

I decided to start with those 2 historical moments to give a little context before sharing more about some of the specific texts and objects Chinami so lovingly preserved and cared for. Some of you know much more than I do, and for some of you this is all new.

I hope others may chime in or make their own posts about Chinami too. And ask questions/make requests too if you want.

You know what they say:

三人よれば文殊の知恵で

(3 people can be as smart as Monju or

two heads are better than one)

You know what they say:

三人よれば文殊の知恵で

(3 people can be as smart as Monju or

two heads are better than one)

Beginning on page 53, Chinami writes about an album her father, Kenji Kondo, left her:

My father left behind a black album. “Scrapbook” is written on the black cover in English along with a picture of a western boy holding a dog’s leash with a little girl next to him. Both the children and the dog are looking off into the distance.

The paper inside the album is also black flock paper. When I open it a photo of Osugi appears first, and then Noe and little Munekazu’s photos are glued to the next page.

I heard that these photos are called gelatine or silver halide photos. As times goes by, the silver leaks out from the edges so that the faces of these three people get blurred. This makes it more sorrowful.

As I continue to flip through the pages of the album there are more photos of Osugi, Noe, their families and siblings. Photos of their coffins, their funeral, and their letters come after. There is even a photo of Masahiko Amakasu’s court martial.

There are photos of Daijiro Furuta, Genjiro Muraki, Kyutaro Wada, Kenji Kurachi, and Koichiro Shintani. They were arrested for planning to assassinate General Masataro Fukuda, who was the Martial Law Commander at the time of the earthquake.

They attacked him without success at the entrance to the venue for the earthquake memorial gathering on September 16, 1924 to avenge the military plot to massacre many Koreans, Chinese, social movement activists, and Osugi and his companions in the aftermath of the earthquake.

There are photos of Daijiro Furuta, who was executed, being placed in a coffin. There is a photo of Katsura Mochizuki and his father. They went to claim Wada’s body after he hung himself in Akita Prison.

There is also a photo of the quiet Unosuke Hisaita, who froze to death on Mt Amagi the year before the earthquake. There are photos of the Kozlov family. There are many photos of comrades from the Labor Movement, Osugi, and others in the album.

I think my father was using this scrapbook album to collect photos to use in The Complete Works of Sakae Osugi, as well to document Muraki’s death, Furuta’s execution, and Wada’s hanging.

He glued the photos in without writing down the names and dates because he was busy with the struggle of the trials and deaths of those close to him.

Now when I see all this, I think that this scrapbook is like a silent protest. I doubt he thought of it as just a place to paste memories.

Moreover, there is one photo of Father looking sad and lonely with the following words written on the back: “On the 2nd Floor of the Labor Union Movement in Katamachi, Komagome, Jan. 1926.”

My father, who felt like the sole survivor, must have been trying to say “I am here too” by pasting that photo, and it pains me to imagine his grief and sadness.

[end quotation]

Here is a photo of Chinami with her mother, Magara, and father, Kenji.

[image description: A young woman and her parents are kneeling on cushions in front of an open door looking at the camera.]

Here is a photo of Chinami with her mother, Magara, and father, Kenji.

[image description: A young woman and her parents are kneeling on cushions in front of an open door looking at the camera.]

Here, Chinami stands behind her mother, Magara. I don& #39;t know who the other two people in this photo are. Maybe you do?

Chinami& #39;s effervescent and playful personality was like a window into a better world to me, as was her steadfast commitment to feminism and anarchism.

[image description: Chinami stands behind an old camera, smiling and looking down.]

[image description: Chinami stands behind an old camera, smiling and looking down.]

Here are two sweet photos of Chinami with her partner, Seisho Shirani. Chinami loved dogs.

[image descriptions: 1) Chinami and Seisho smiling at the camera. Chinami is flashing a "peace" sign. 2) Chinami and Seisho sitting with two dogs outside.]

[image descriptions: 1) Chinami and Seisho smiling at the camera. Chinami is flashing a "peace" sign. 2) Chinami and Seisho sitting with two dogs outside.]

On June 6, 2010, 2 weeks before her sudden passing, Chinami spoke at a symposium marking the 100th anniversary of the High Treason Incident hosted by the Contemporary Women’s Culture Institute ( http://www.gjk-j.com/ ).">https://www.gjk-j.com/">...

The memorial collection of her writings edited by Seisho Shirani begins with the following speech:

[image description: Chinami Kondo, with her hair pulled back and wearing a turtleneck, speaking into a microphone.]

[image description: Chinami Kondo, with her hair pulled back and wearing a turtleneck, speaking into a microphone.]

I am the daughter of Toshihiko Sakai’s daughter Magara and Kondo Kenji. All the while thinking that socialists don’t pass on inheritance, I ended up in the position of “Caretaker of the Kondo Library,” taking care of the things entrusted to me by my father and mother.

[end quotation]

Seisho Shirani gave me a feminist calendar in 2012. Magara, Chinami& #39;s mother, is featured for the month of May, and I always keep the calendar open to that page. Here is a picture of me with the calendar.

Seisho Shirani gave me a feminist calendar in 2012. Magara, Chinami& #39;s mother, is featured for the month of May, and I always keep the calendar open to that page. Here is a picture of me with the calendar.

Getty images have a great picture of Magara here: https://www.gettyimages.ca/detail/news-photo/activist-magara-kondo-speaks-during-the-asahi-shimbun-news-photo/1207885995

Magara">https://www.gettyimages.ca/detail/ne... was 19 yrs old when she and comrades organized Sekirankai. She passed away in 1983. Kenji had passed away 14 years earlier. Chinami writes about his final years on page 59:

Magara">https://www.gettyimages.ca/detail/ne... was 19 yrs old when she and comrades organized Sekirankai. She passed away in 1983. Kenji had passed away 14 years earlier. Chinami writes about his final years on page 59:

After the war my father continued to work for the Commoners& #39; Paper and also joined the anarchist movement, but he spent most of his days in the 1960s with intracranial hemorrhaging and its effects.

He lived on the tatami, representing those whose lives had been cut short before their time, and he died with a black flag wrapped around him.

Then, beginning with Jiro Yasunari, Katsura Mochizuki, and Taiji Yamaga, many of my father& #39;s comrades offered their warm condolences to my family. My mother& #39;s response to all this was to say, "Anarchists are so sweet."

Then, my mother joined the movement to preserve Munekazu& #39;s gravestone and went on to do some things my father might have done too had he lived longer.

[end quotation]

[end quotation]

A few years back @Justseeds published some manga Taiji Yamaga drew to chronicle much of the same histories I& #39;m writing about in this thread. Please check this out and the book with the rest: https://s1gnal.org/post/35775084991/signal-02-excerpt-the-yamaga-manga">https://s1gnal.org/post/3577...

Returning to the speech that Chinami made for the 100th anniversary of the High Treason Incident:

My grandfather Toshihiko Sakai was one year older than Shusui Kotoku, and their friendship was a long one.

[images: photos of Sakai (left) and Kotoku (right)]

My grandfather Toshihiko Sakai was one year older than Shusui Kotoku, and their friendship was a long one.

[images: photos of Sakai (left) and Kotoku (right)]

In 1903 (Meiji 36) they started printing antiwar treatises and resigned from Yorozu Choho [the largest newspaper in Japan at the time] together. Gingetsu Ito, who was a journalist for Yorozu Choho at the time, wrote the following in the first issue of the Commoners’ Paper:

“Shusui is the person who rolls the socialist rice dumplings (dango), and Karagawa [Sakai’s alias or pen name] is the one who boils the red beans.”

I think this speaks to how important and necessary their relationship was for each other.

[Dango: http://www.oksfood.com/sweets/anko_dango.html]">https://www.oksfood.com/sweets/an...

I think this speaks to how important and necessary their relationship was for each other.

[Dango: http://www.oksfood.com/sweets/anko_dango.html]">https://www.oksfood.com/sweets/an...

Kotoku was arrested in the High Treason Incident while my grandfather was locked up for the Red Flag Incident (1908). If he& #39;d been out at the time he surely would have been implicated too.

After he was released my grandfather’s days were busy, first with legal correspondence and sending care packages for those imprisoned, and then he handled communicating with the bereaved families of the executed.

As a way for him and his remaining comrades to make a living, he started the manuscript and copyediting service called Baibunsha. My father, Kenji Kondo, was in the movement with Sakae Osugi.

At the time of the Great Kanto Earthquake, my grandfather was imprisoned for the First Communist Party Incident, and my father, who was in protective custody in jail, learned of Osugi’s death when he was out on probation.

My mother, Magara, had also been caught and locked up for the First Communist Party Incident.

It’s as if they always somehow managed to survive under the “protection” of the authorities through intensely dangerous times.

It’s as if they always somehow managed to survive under the “protection” of the authorities through intensely dangerous times.

So having lost so many to the High Treason Incident and then Osugi and the many victims of the White Terror after the Great Kanto Earthquake, as well as all those who were arrested and killed themselves, my grandfather and parents naturally ended up as caretakers for ...

... many of their comrades’ and mentors’ belongings and other materials. And so that’s how I came to call myself “The Caretaker of the Kondo Library.”

[photograph of Chinami Kondo, with her hair pulled back, looking down.]

[photograph of Chinami Kondo, with her hair pulled back, looking down.]

I brought one of those items called the “Treason Album” with me today because I wanted you to see it. Originally it was a scrapbook Kotoku used to collect things like newspaper clippings from his stay in America. There are still traces you can see from where they were removed.

Then letters Kotoku and others wrote from prison were later pasted in along with the title “Mr. Sakai’s Treason Album.”

[Photo by Jong Pairez of Seisho Shirani holding the album open.]

[Photo by Jong Pairez of Seisho Shirani holding the album open.]

[end quotation]

Before continuing I want to point out this album and much of what made up the “Kondo Library" survived multiple police raids, the earthquake, and all sorts of state repression. Chinami’s mother, Magara, was still a child at the time of the High Treason Incident.

Before continuing I want to point out this album and much of what made up the “Kondo Library" survived multiple police raids, the earthquake, and all sorts of state repression. Chinami’s mother, Magara, was still a child at the time of the High Treason Incident.

The decision to hide some things among Magara’s toys and books proved wise since the police never went through what they believed to be just children’s things.

[Photo by Jong Pairez of Seisho Shirani holding the album closed.]

[Photo by Jong Pairez of Seisho Shirani holding the album closed.]

Writings that survived thanks to Chinami and her family have been important primary sources referenced in many works in many languages. It’s no exaggeration to say that the efforts to preserve these items made it possible for us to learn about the history of anarchism in Japan.

As just 1 example, Mikiso Hane writes about many of these letters in his book Reflections on the Way to the Gallows. Here is his translation (p. 129) of the heartbreaking and tender postcard Suga Kanno wrote from prison (just before she was executed) to Chinami& #39;s mother, Magara:

"January 24. Ma-san: Thank you for the beautiful postcard. You seem to be doing well in your studies. Your handwriting is very good. I am impressed. Have your mother make a tunic out of the upper garment I am giving you.

Also, I want you to have the doll, the pretty boxes, and the cute needles in the drawer. These are with my belongings. Have your parents pick them out for you. I would like to see your adorable face just once more. Goodbye."

[Photo of Suga (or Sugako) Kanno]

[Photo of Suga (or Sugako) Kanno]

[end quotation]

Chinami’s grandparents kept this album, hiding it among Magara’s things whenever the house was searched. Magara passed it down to Chinami. The whimsical, candy wrapper-like cover guarded many writings you may have studied in books.

Chinami’s grandparents kept this album, hiding it among Magara’s things whenever the house was searched. Magara passed it down to Chinami. The whimsical, candy wrapper-like cover guarded many writings you may have studied in books.

Over a century of anti-anarchist propaganda and brutal state repression, which obviously continue, have made the documenting of our histories fraught with challenges and dangers. The archiving and preservation of things like the Treason Album are both necessary and difficult.

I will share more stories about the Kondo Library later this month.

Since tomorrow is the 10th anniversary of Chinami’s sudden passing, I want to share some other things first.

Near the end of her speech for the 100th anniversary of the High Treason Incident Chinami said:

Since tomorrow is the 10th anniversary of Chinami’s sudden passing, I want to share some other things first.

Near the end of her speech for the 100th anniversary of the High Treason Incident Chinami said:

I’ve been thinking about how to hold onto the legacy of the High Treason Incident 100 years later and carry it with me in movements going forward.

[photo of Chinami Kondo with her hair pulled back, speaking into a microphone.]

[photo of Chinami Kondo with her hair pulled back, speaking into a microphone.]

When I protest against the bases in Okinawa or march for May Day and police come from behind to rough people up or when undercover cops surround and arrest someone, I understand our present situation is gravely serious too.

[end quotation]

[Photo of Chinami at a protest.]

[end quotation]

[Photo of Chinami at a protest.]

That was on June 6, 2010 at the symposium hosted by the Contemporary Women’s Culture Institute ( http://www.gjk-j.com/ ).">https://www.gjk-j.com/">... Chinami spoke on a panel with Susumu Yamaizumi and Satoshi Kamata. She continued with other feminist and anarchist projects in the days after this event.

On June 15th Chinami went to the doctor for what she thought was a summer cold. A chest exam showed an acute AD (acute dissection) and she was hospitalized. After 3 days she was moved from the ICU to a regular hospital room. On June 20th, she died. She was not yet 69 years old.

Chinami was involved in much more than preserving radical history. As just 1 example,in 2006 she started blogging to preserve and save the Fusen Kaikan women& #39;s center and to honor her feminist mentor Fusae Ichikawa.

[Photo of Chinami (left) and Fusae Ichikawa]

[Photo of Chinami (left) and Fusae Ichikawa]

In July of 2007 the Fusen Kaikan was condemned and an eviction notice was served. 6 of the 8 people working there were laid off, the reason given being that it was no longer necessary to fund the study of women& #39;s issues. Chinami fought back against this too! More on this later.

And here are 4 wonderful photos of Chinami I hope you will spend some time admiring.

[Chinami pensive at a desk, Chinami animated in a purple blouse, Chinami with short hair looking delighted, and Chinami with a warm smile, hair pulled back]

[Chinami pensive at a desk, Chinami animated in a purple blouse, Chinami with short hair looking delighted, and Chinami with a warm smile, hair pulled back]

My heart is with Seisho Shirani and all of Chinami’s friends and comrades as day breaks on the 10th anniversary of her passing.

[photo of Chinami on a bus in a window seat, leaning toward the window. Her hair is pulled back. She looks so cool.]

[photo of Chinami on a bus in a window seat, leaning toward the window. Her hair is pulled back. She looks so cool.]

To mark the 10th anniversary of Chinami Kondo& #39;s passing @cira_japana shared this tweet with a great photo of the album described above. You can see how it would have fit right in with children& #39;s things. Translation follows. https://twitter.com/cira_japana/status/1274258120944914433?s=20">https://twitter.com/cira_japa...

"Today is the 10-year anniversary of Chinami Kondo& #39;s death. She took care of precious materials left to her by her grandfather (Toshihiko Sakai) and parents (Kenji and Magara Kondo). Letters from those imprisoned for the High Treason Incident were pasted in the Treason Album,

which was never seized by the police because it looked like a child& #39;s album. It wasn& #39;t that long ago that saving documents meant risking one& #39;s life."

Alas, it& #39;s still that way for many ...

@cira_japana also posted another tweet about Chinami that follows.

Alas, it& #39;s still that way for many ...

@cira_japana also posted another tweet about Chinami that follows.

Munekazu Tachibana was the 6 yr. old child murdered along with Ito and Osugi. Here are 2 photos of Chinami at memorial gatherings at his grave in 1988 on the left and 1992 on the right. More follows. https://twitter.com/cira_japana/status/1274258567344738304?s=20">https://twitter.com/cira_japa...

The photo on the left pictures Chinami with Yoshio Waseda and Junji Hoshino, who were in the Rural Youth Organization, and Sakaru Endo, the 1st postwar translator of Emma Goldman& #39;s works into Japanese. The photo on the right pictures Chinami with Ito and Osugi& #39;s children,

the two Emmas (Emiko and Sachiko), Louis (Rui), and Sakaru Endo.

Thank you so much for these tweets @cira_japana!

心を打つ写真です!

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="💔" title="Gebrochenes Herz" aria-label="Emoji: Gebrochenes Herz">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="💔" title="Gebrochenes Herz" aria-label="Emoji: Gebrochenes Herz"> https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="💔" title="Gebrochenes Herz" aria-label="Emoji: Gebrochenes Herz">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="💔" title="Gebrochenes Herz" aria-label="Emoji: Gebrochenes Herz"> https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="💔" title="Gebrochenes Herz" aria-label="Emoji: Gebrochenes Herz">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="💔" title="Gebrochenes Herz" aria-label="Emoji: Gebrochenes Herz"> https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="💗" title="Wachsendes Herz" aria-label="Emoji: Wachsendes Herz">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="💗" title="Wachsendes Herz" aria-label="Emoji: Wachsendes Herz"> https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="💗" title="Wachsendes Herz" aria-label="Emoji: Wachsendes Herz">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="💗" title="Wachsendes Herz" aria-label="Emoji: Wachsendes Herz"> https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="💗" title="Wachsendes Herz" aria-label="Emoji: Wachsendes Herz">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="💗" title="Wachsendes Herz" aria-label="Emoji: Wachsendes Herz"> https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🏴" title="Wehende schwarze Flagge" aria-label="Emoji: Wehende schwarze Flagge">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🏴" title="Wehende schwarze Flagge" aria-label="Emoji: Wehende schwarze Flagge"> https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🏴" title="Wehende schwarze Flagge" aria-label="Emoji: Wehende schwarze Flagge">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🏴" title="Wehende schwarze Flagge" aria-label="Emoji: Wehende schwarze Flagge"> https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🏴" title="Wehende schwarze Flagge" aria-label="Emoji: Wehende schwarze Flagge">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🏴" title="Wehende schwarze Flagge" aria-label="Emoji: Wehende schwarze Flagge">

Thank you so much for these tweets @cira_japana!

心を打つ写真です!

Here are more photos of Chinami I hope you will admire on this 10th anniversary of her passing.

[Chinami pouring tea, Chinami laughing at a table with other people looking at papers, young Chinami appearing on tv, and young Chinami in a light green shirt looking at the camera.]

[Chinami pouring tea, Chinami laughing at a table with other people looking at papers, young Chinami appearing on tv, and young Chinami in a light green shirt looking at the camera.]

This is a great photo of Chinami marching with comrades to go along with the tribute @Justseeds has here:

https://justseeds.org/celebrate-peoples-history-1-seki-ran-kai/

"Her">https://justseeds.org/celebrate... quietly marching figure was beautiful to behold."

Special https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="❤️" title="Rotes Herz" aria-label="Emoji: Rotes Herz">to @yaiyaiyuki and @IrregularRhythm

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="❤️" title="Rotes Herz" aria-label="Emoji: Rotes Herz">to @yaiyaiyuki and @IrregularRhythm

https://justseeds.org/celebrate-peoples-history-1-seki-ran-kai/

"Her">https://justseeds.org/celebrate... quietly marching figure was beautiful to behold."

Special

I mentioned Chinami loved dogs.

Her friends may also remember a very special little singing bird she had.

You can think of me as that bird as I tell this next story:

Her friends may also remember a very special little singing bird she had.

You can think of me as that bird as I tell this next story:

Once upon a time we all were at Chinami & Seisho’s table, enjoying a delicious vegan osechi New Year’s feast in the midst of the Kondo Library, which was their home.

Imagine the most magical, special time ever, and that was that.

Imagine the most magical, special time ever, and that was that.

Of course the albums I wrote about were there. The walls were covered in all sorts of anarchist flyers, art, and treasures.

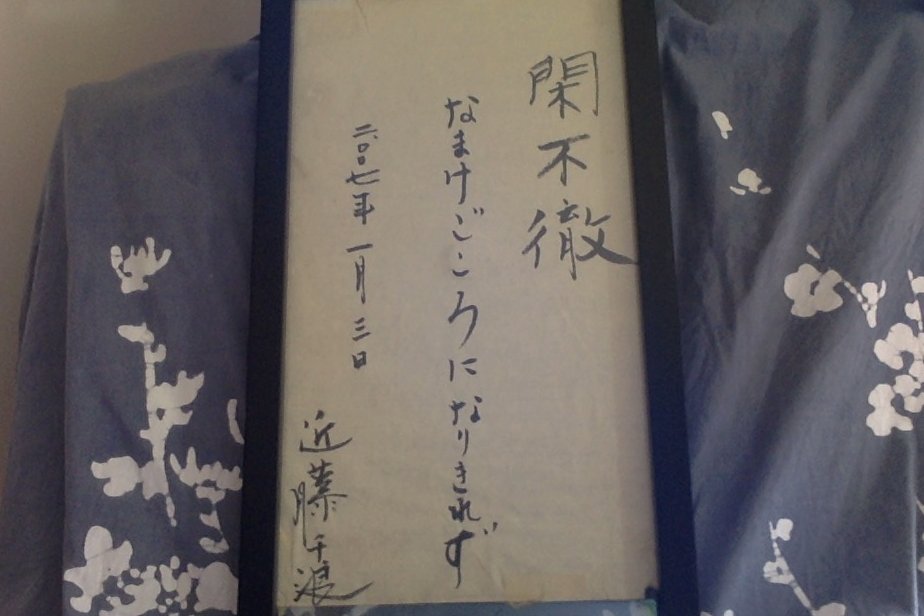

Chinami talked about this hand-carved wooden sign.

Chinami talked about this hand-carved wooden sign.

Individually those characters carved into the wood mean “leisure” or “free time” and “inconsistent” or “flexible” (or “half-assed”).

It& #39;s pronounced Kanfutetsu.

The meaning was not immediately apparent to me at all!

It& #39;s pronounced Kanfutetsu.

The meaning was not immediately apparent to me at all!

Here’s how Chinami explained this concept in her handwriting with her signature at the time.

This means something like “never stop cultivating a lazy heart” or “keep on with a lazy spirit.”

Dated Jan. 3, 2007

This means something like “never stop cultivating a lazy heart” or “keep on with a lazy spirit.”

Dated Jan. 3, 2007

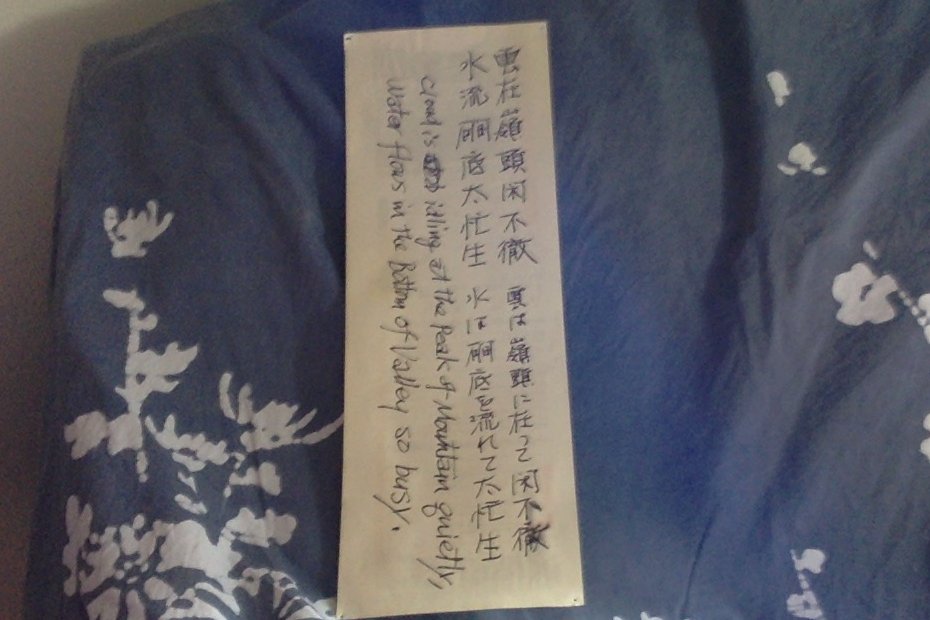

The wooden sign was made by Goyo Nakano (中野五葉) who was a monk at Kankoji (関興寺), a Rinzai Zen Buddhist temple in Niigata, and he gifted it to anarchists.

(Remember that an anarchist Zen monk, Uchiyama, had been among those executed in the High Treason Incident.)

(Remember that an anarchist Zen monk, Uchiyama, had been among those executed in the High Treason Incident.)

The phrase comes from Rinzai scripture, and Seisho Shirani copied out the original text, as well as his English translation in his handwriting:

“Cloud is idling at the Peak of Mountain quietly,

Water flows in the Bottom of Valley so busy.”

“Cloud is idling at the Peak of Mountain quietly,

Water flows in the Bottom of Valley so busy.”

Keeping a “lazy heart” or “lazy spirit” is to be like the idling cloud. Not busy.

Sure, we can be like water like Bruce Lee said.

But also, we can be like cloud!

#閑不徹 #kanfutetsu

Sure, we can be like water like Bruce Lee said.

But also, we can be like cloud!

#閑不徹 #kanfutetsu

We learn laziness is a bad thing. It& #39;s no accident. Who that gets weaponized against, who it harms, who it kills isn& #39;t an accident either. For some more than others the alternative to kanfutetsu can mean illness and early death. #閑不徹

There& #39;s still so much left to share. I will return to add to this thread for Chinami& #39;s birthday in September, if not sooner.

#閑不徹

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="☁️" title="Wolke" aria-label="Emoji: Wolke">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="☁️" title="Wolke" aria-label="Emoji: Wolke"> https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="☁️" title="Wolke" aria-label="Emoji: Wolke">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="☁️" title="Wolke" aria-label="Emoji: Wolke"> https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="☁️" title="Wolke" aria-label="Emoji: Wolke">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="☁️" title="Wolke" aria-label="Emoji: Wolke"> https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="☁️" title="Wolke" aria-label="Emoji: Wolke">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="☁️" title="Wolke" aria-label="Emoji: Wolke"> https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="☁️" title="Wolke" aria-label="Emoji: Wolke">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="☁️" title="Wolke" aria-label="Emoji: Wolke">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="💜" title="Violettes Herz" aria-label="Emoji: Violettes Herz">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="💜" title="Violettes Herz" aria-label="Emoji: Violettes Herz"> https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="❤️" title="Rotes Herz" aria-label="Emoji: Rotes Herz">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="❤️" title="Rotes Herz" aria-label="Emoji: Rotes Herz"> https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="💜" title="Violettes Herz" aria-label="Emoji: Violettes Herz">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="💜" title="Violettes Herz" aria-label="Emoji: Violettes Herz"> https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="❤️" title="Rotes Herz" aria-label="Emoji: Rotes Herz">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="❤️" title="Rotes Herz" aria-label="Emoji: Rotes Herz"> https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="💜" title="Violettes Herz" aria-label="Emoji: Violettes Herz">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="💜" title="Violettes Herz" aria-label="Emoji: Violettes Herz">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🏴" title="Wehende schwarze Flagge" aria-label="Emoji: Wehende schwarze Flagge">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🏴" title="Wehende schwarze Flagge" aria-label="Emoji: Wehende schwarze Flagge"> https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🏴" title="Wehende schwarze Flagge" aria-label="Emoji: Wehende schwarze Flagge">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🏴" title="Wehende schwarze Flagge" aria-label="Emoji: Wehende schwarze Flagge"> https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🏴" title="Wehende schwarze Flagge" aria-label="Emoji: Wehende schwarze Flagge">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🏴" title="Wehende schwarze Flagge" aria-label="Emoji: Wehende schwarze Flagge"> https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🏴" title="Wehende schwarze Flagge" aria-label="Emoji: Wehende schwarze Flagge">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🏴" title="Wehende schwarze Flagge" aria-label="Emoji: Wehende schwarze Flagge"> https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🏴" title="Wehende schwarze Flagge" aria-label="Emoji: Wehende schwarze Flagge">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🏴" title="Wehende schwarze Flagge" aria-label="Emoji: Wehende schwarze Flagge">

#閑不徹

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter![[end quotation]Here is a photo of Chinami with her mother, Magara, and father, Kenji.[image description: A young woman and her parents are kneeling on cushions in front of an open door looking at the camera.] [end quotation]Here is a photo of Chinami with her mother, Magara, and father, Kenji.[image description: A young woman and her parents are kneeling on cushions in front of an open door looking at the camera.]](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/EZ6QSikWAAAF0PB.png)

![[image description: Magara stands behind Chinami, who is seated.] [image description: Magara stands behind Chinami, who is seated.]](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/EZ6RpYHWsAIQC8G.jpg)

![Chinami& #39;s effervescent and playful personality was like a window into a better world to me, as was her steadfast commitment to feminism and anarchism. [image description: Chinami stands behind an old camera, smiling and looking down.] Chinami& #39;s effervescent and playful personality was like a window into a better world to me, as was her steadfast commitment to feminism and anarchism. [image description: Chinami stands behind an old camera, smiling and looking down.]](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/EZ6UC5hXQAAlA3C.png)

![Here are two sweet photos of Chinami with her partner, Seisho Shirani. Chinami loved dogs.[image descriptions: 1) Chinami and Seisho smiling at the camera. Chinami is flashing a "peace" sign. 2) Chinami and Seisho sitting with two dogs outside.] Here are two sweet photos of Chinami with her partner, Seisho Shirani. Chinami loved dogs.[image descriptions: 1) Chinami and Seisho smiling at the camera. Chinami is flashing a "peace" sign. 2) Chinami and Seisho sitting with two dogs outside.]](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/EZ6VGdiXsAAwmNW.jpg)

![Here are two sweet photos of Chinami with her partner, Seisho Shirani. Chinami loved dogs.[image descriptions: 1) Chinami and Seisho smiling at the camera. Chinami is flashing a "peace" sign. 2) Chinami and Seisho sitting with two dogs outside.] Here are two sweet photos of Chinami with her partner, Seisho Shirani. Chinami loved dogs.[image descriptions: 1) Chinami and Seisho smiling at the camera. Chinami is flashing a "peace" sign. 2) Chinami and Seisho sitting with two dogs outside.]](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/EZ6VGk0XsAA_yIj.jpg)

![The memorial collection of her writings edited by Seisho Shirani begins with the following speech:[image description: Chinami Kondo, with her hair pulled back and wearing a turtleneck, speaking into a microphone.] The memorial collection of her writings edited by Seisho Shirani begins with the following speech:[image description: Chinami Kondo, with her hair pulled back and wearing a turtleneck, speaking into a microphone.]](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/EZ6zjeFWkAE8A9b.png)

![[end quotation]Seisho Shirani gave me a feminist calendar in 2012. Magara, Chinami& #39;s mother, is featured for the month of May, and I always keep the calendar open to that page. Here is a picture of me with the calendar. [end quotation]Seisho Shirani gave me a feminist calendar in 2012. Magara, Chinami& #39;s mother, is featured for the month of May, and I always keep the calendar open to that page. Here is a picture of me with the calendar.](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/EaKkSgSWAAYQmf2.jpg)

![Returning to the speech that Chinami made for the 100th anniversary of the High Treason Incident:My grandfather Toshihiko Sakai was one year older than Shusui Kotoku, and their friendship was a long one. [images: photos of Sakai (left) and Kotoku (right)] Returning to the speech that Chinami made for the 100th anniversary of the High Treason Incident:My grandfather Toshihiko Sakai was one year older than Shusui Kotoku, and their friendship was a long one. [images: photos of Sakai (left) and Kotoku (right)]](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/EauV_8MXYAIAKPq.jpg)

![Returning to the speech that Chinami made for the 100th anniversary of the High Treason Incident:My grandfather Toshihiko Sakai was one year older than Shusui Kotoku, and their friendship was a long one. [images: photos of Sakai (left) and Kotoku (right)] Returning to the speech that Chinami made for the 100th anniversary of the High Treason Incident:My grandfather Toshihiko Sakai was one year older than Shusui Kotoku, and their friendship was a long one. [images: photos of Sakai (left) and Kotoku (right)]](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/EauWAx7XQAEWtZ6.jpg)

![... many of their comrades’ and mentors’ belongings and other materials. And so that’s how I came to call myself “The Caretaker of the Kondo Library.”[photograph of Chinami Kondo, with her hair pulled back, looking down.] ... many of their comrades’ and mentors’ belongings and other materials. And so that’s how I came to call myself “The Caretaker of the Kondo Library.”[photograph of Chinami Kondo, with her hair pulled back, looking down.]](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/Eau_cTfWAAYlmdC.jpg)

![Then letters Kotoku and others wrote from prison were later pasted in along with the title “Mr. Sakai’s Treason Album.”[Photo by Jong Pairez of Seisho Shirani holding the album open.] Then letters Kotoku and others wrote from prison were later pasted in along with the title “Mr. Sakai’s Treason Album.”[Photo by Jong Pairez of Seisho Shirani holding the album open.]](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/Ea0GlbaWkAUEGjk.jpg)

![The decision to hide some things among Magara’s toys and books proved wise since the police never went through what they believed to be just children’s things.[Photo by Jong Pairez of Seisho Shirani holding the album closed.] The decision to hide some things among Magara’s toys and books proved wise since the police never went through what they believed to be just children’s things.[Photo by Jong Pairez of Seisho Shirani holding the album closed.]](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/Ea0ICgYWoAIqqrq.jpg)

![Also, I want you to have the doll, the pretty boxes, and the cute needles in the drawer. These are with my belongings. Have your parents pick them out for you. I would like to see your adorable face just once more. Goodbye."[Photo of Suga (or Sugako) Kanno] Also, I want you to have the doll, the pretty boxes, and the cute needles in the drawer. These are with my belongings. Have your parents pick them out for you. I would like to see your adorable face just once more. Goodbye."[Photo of Suga (or Sugako) Kanno]](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/Ea0Ot-SXYAERci5.jpg)

![I’ve been thinking about how to hold onto the legacy of the High Treason Incident 100 years later and carry it with me in movements going forward. [photo of Chinami Kondo with her hair pulled back, speaking into a microphone.] I’ve been thinking about how to hold onto the legacy of the High Treason Incident 100 years later and carry it with me in movements going forward. [photo of Chinami Kondo with her hair pulled back, speaking into a microphone.]](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/Ea5BKP5WAAA_Gs7.jpg)

![When I protest against the bases in Okinawa or march for May Day and police come from behind to rough people up or when undercover cops surround and arrest someone, I understand our present situation is gravely serious too.[end quotation][Photo of Chinami at a protest.] When I protest against the bases in Okinawa or march for May Day and police come from behind to rough people up or when undercover cops surround and arrest someone, I understand our present situation is gravely serious too.[end quotation][Photo of Chinami at a protest.]](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/Ea5BUyWWkAIrfzv.jpg)

![Chinami was involved in much more than preserving radical history. As just 1 example,in 2006 she started blogging to preserve and save the Fusen Kaikan women& #39;s center and to honor her feminist mentor Fusae Ichikawa.[Photo of Chinami (left) and Fusae Ichikawa] Chinami was involved in much more than preserving radical history. As just 1 example,in 2006 she started blogging to preserve and save the Fusen Kaikan women& #39;s center and to honor her feminist mentor Fusae Ichikawa.[Photo of Chinami (left) and Fusae Ichikawa]](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/Ea5CdGhXkAQ88j9.jpg)

![And here are 4 wonderful photos of Chinami I hope you will spend some time admiring.[Chinami pensive at a desk, Chinami animated in a purple blouse, Chinami with short hair looking delighted, and Chinami with a warm smile, hair pulled back] And here are 4 wonderful photos of Chinami I hope you will spend some time admiring.[Chinami pensive at a desk, Chinami animated in a purple blouse, Chinami with short hair looking delighted, and Chinami with a warm smile, hair pulled back]](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/Ea5D13JXsAErkuV.jpg)

![And here are 4 wonderful photos of Chinami I hope you will spend some time admiring.[Chinami pensive at a desk, Chinami animated in a purple blouse, Chinami with short hair looking delighted, and Chinami with a warm smile, hair pulled back] And here are 4 wonderful photos of Chinami I hope you will spend some time admiring.[Chinami pensive at a desk, Chinami animated in a purple blouse, Chinami with short hair looking delighted, and Chinami with a warm smile, hair pulled back]](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/Ea5D14oWoAAtXoX.jpg)

![And here are 4 wonderful photos of Chinami I hope you will spend some time admiring.[Chinami pensive at a desk, Chinami animated in a purple blouse, Chinami with short hair looking delighted, and Chinami with a warm smile, hair pulled back] And here are 4 wonderful photos of Chinami I hope you will spend some time admiring.[Chinami pensive at a desk, Chinami animated in a purple blouse, Chinami with short hair looking delighted, and Chinami with a warm smile, hair pulled back]](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/Ea5D17aXQAIQuSr.jpg)

![And here are 4 wonderful photos of Chinami I hope you will spend some time admiring.[Chinami pensive at a desk, Chinami animated in a purple blouse, Chinami with short hair looking delighted, and Chinami with a warm smile, hair pulled back] And here are 4 wonderful photos of Chinami I hope you will spend some time admiring.[Chinami pensive at a desk, Chinami animated in a purple blouse, Chinami with short hair looking delighted, and Chinami with a warm smile, hair pulled back]](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/Ea5D19RWoAQM_jk.jpg)

![My heart is with Seisho Shirani and all of Chinami’s friends and comrades as day breaks on the 10th anniversary of her passing.[photo of Chinami on a bus in a window seat, leaning toward the window. Her hair is pulled back. She looks so cool.] My heart is with Seisho Shirani and all of Chinami’s friends and comrades as day breaks on the 10th anniversary of her passing.[photo of Chinami on a bus in a window seat, leaning toward the window. Her hair is pulled back. She looks so cool.]](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/Ea6IUMzXkAEw1DU.jpg)

![Here are more photos of Chinami I hope you will admire on this 10th anniversary of her passing.[Chinami pouring tea, Chinami laughing at a table with other people looking at papers, young Chinami appearing on tv, and young Chinami in a light green shirt looking at the camera.] Here are more photos of Chinami I hope you will admire on this 10th anniversary of her passing.[Chinami pouring tea, Chinami laughing at a table with other people looking at papers, young Chinami appearing on tv, and young Chinami in a light green shirt looking at the camera.]](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/Ea-j_ezWAAMcGdb.jpg)

![Here are more photos of Chinami I hope you will admire on this 10th anniversary of her passing.[Chinami pouring tea, Chinami laughing at a table with other people looking at papers, young Chinami appearing on tv, and young Chinami in a light green shirt looking at the camera.] Here are more photos of Chinami I hope you will admire on this 10th anniversary of her passing.[Chinami pouring tea, Chinami laughing at a table with other people looking at papers, young Chinami appearing on tv, and young Chinami in a light green shirt looking at the camera.]](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/Ea-kAj8XsAIoAUc.jpg)

![Here are more photos of Chinami I hope you will admire on this 10th anniversary of her passing.[Chinami pouring tea, Chinami laughing at a table with other people looking at papers, young Chinami appearing on tv, and young Chinami in a light green shirt looking at the camera.] Here are more photos of Chinami I hope you will admire on this 10th anniversary of her passing.[Chinami pouring tea, Chinami laughing at a table with other people looking at papers, young Chinami appearing on tv, and young Chinami in a light green shirt looking at the camera.]](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/Ea-kCBtXQAEjVaO.jpg)

![Here are more photos of Chinami I hope you will admire on this 10th anniversary of her passing.[Chinami pouring tea, Chinami laughing at a table with other people looking at papers, young Chinami appearing on tv, and young Chinami in a light green shirt looking at the camera.] Here are more photos of Chinami I hope you will admire on this 10th anniversary of her passing.[Chinami pouring tea, Chinami laughing at a table with other people looking at papers, young Chinami appearing on tv, and young Chinami in a light green shirt looking at the camera.]](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/Ea-kCnjWAAEdV7p.jpg)

to @yaiyaiyuki and @IrregularRhythm" title="This is a great photo of Chinami marching with comrades to go along with the tribute @Justseeds has here: https://justseeds.org/celebrate... quietly marching figure was beautiful to behold."Special https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="❤️" title="Rotes Herz" aria-label="Emoji: Rotes Herz">to @yaiyaiyuki and @IrregularRhythm" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

to @yaiyaiyuki and @IrregularRhythm" title="This is a great photo of Chinami marching with comrades to go along with the tribute @Justseeds has here: https://justseeds.org/celebrate... quietly marching figure was beautiful to behold."Special https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="❤️" title="Rotes Herz" aria-label="Emoji: Rotes Herz">to @yaiyaiyuki and @IrregularRhythm" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>