A month back I was asked about dating the Babylonian Fürstenspiegel, aka Advice to a Prince. Because I& #39;m absolutely procrastinating having to slog through Schloen& #39;s "The House of the Father" (again), y& #39;all get to have little a cuneiform knowledge -- as a treat!

I will be calling this text "šarru ana dīnim lā iqūl" for reasons that will be clear in a little bit. Some people call this text the Babylonian Fürstenspiegel because this is what Landsberger and de Liagre Böhl called it back in the mid-30s.

Other people call it "Advice for a Prince" (Lambert 1960), "a Babylonian political pamphlet" (Diakonoff 1965), and even an ancient forgery (Biggs 2004). The reason why Fürstenspiegel has been so appealing is because, at first glace, the text looks like it belongs to this genre.

Fürstenspiegel is a genre dedicated to how individuals in power should act. The name itself is german, though Dutch, English, and as has been argued Arabic, Turkish, and Persian cultures all have their own similar traditions. In theory, its world literature!

I don& #39;t really buy this distinction -- to me this is  https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="💯" title="Hundred points symbol" aria-label="Emoji: Hundred points symbol"> teleological in that we see exactly how this text can fit inside our notion of how political powers should act. Plus de Liagre Böhl, the scholar who published the first critical study of this text literally tells us this:

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="💯" title="Hundred points symbol" aria-label="Emoji: Hundred points symbol"> teleological in that we see exactly how this text can fit inside our notion of how political powers should act. Plus de Liagre Böhl, the scholar who published the first critical study of this text literally tells us this:

"A renewed treatment of this [text] is certainly in place, not only because of its importance of text within the framework of contemporary history, but also in terms of its form in terms of its place upon... so-called wisdom literature" (Böhl 1937, 3).

In my larger article I make a big stink about how we shouldn& #39;t even bother calling this text "wisdom literature" either, since this term, also modern, had been fashioned in order to create order out of ancient compiled literary works found in the Writings section of the TaNaKh.

Anyway.

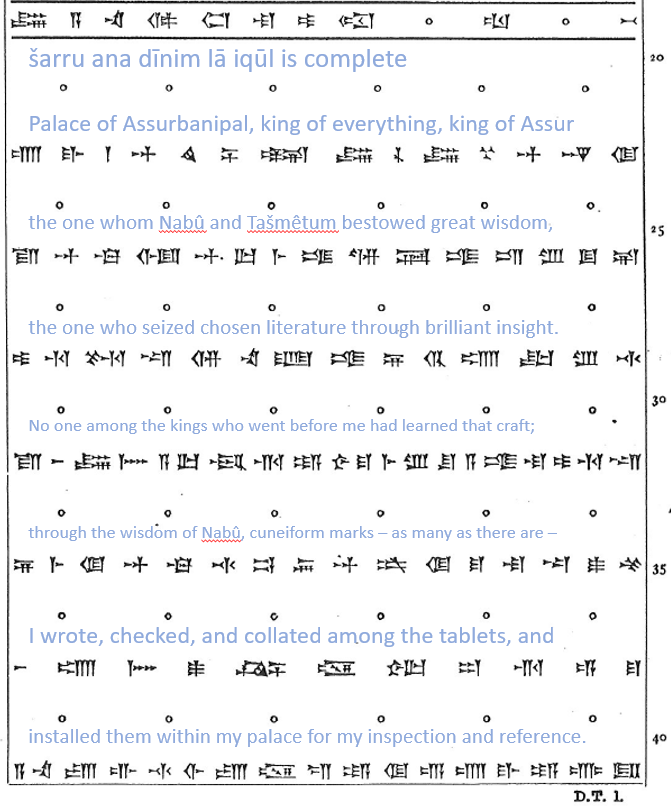

D(aily) T(elegraph) 1 was the only copy we had of šarru ana dīnim lā iqūl between 1873 and 1973. It was dug up by George Smith, the famed Gilgamesh translator who "began to undress himself" whilst reading through the 11th tablet.

D(aily) T(elegraph) 1 was the only copy we had of šarru ana dīnim lā iqūl between 1873 and 1973. It was dug up by George Smith, the famed Gilgamesh translator who "began to undress himself" whilst reading through the 11th tablet.

DT 1 had been found within the confines of "Ashurbanipal& #39;s library," who began procuring tablets from Borsippa around 664 BCE (Frame and George 2005).

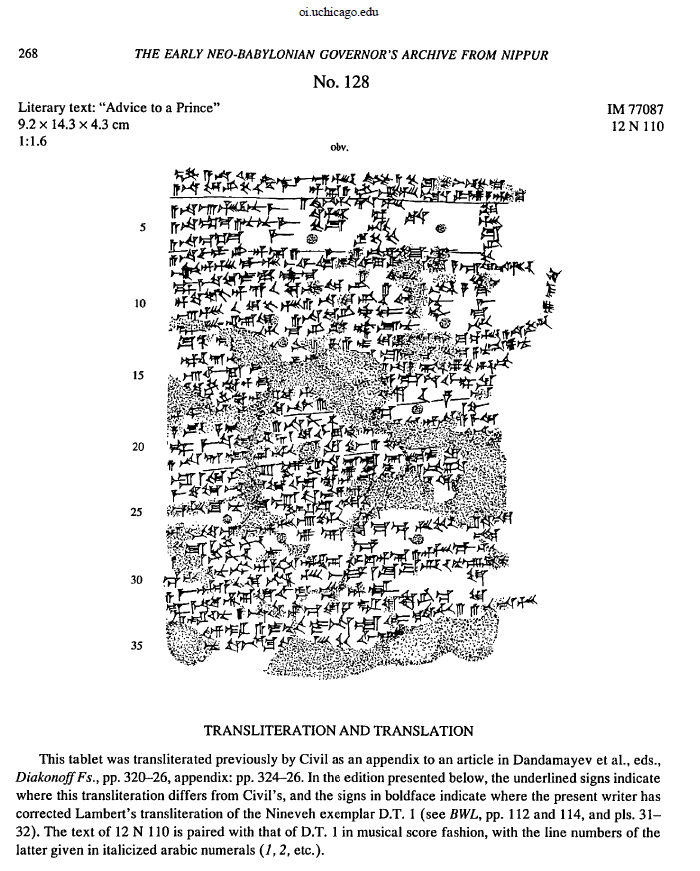

In 1973, the Oriental Institute at Chicago, in excavating an area of Nippur under McGuire Gibson, found a cache of texts belonging to the retinue of the city& #39;s governor (šandabakku); one of the tablets turned out to be šarru ana dīnim lā iqūl, dating to the mid-8th century BCE.

Initially published by Reiner and Civil for Diakonoff& #39;s Festschrift in 1982, the text was collated and published by Steven Cole in 1996, which is free for download on the University of Chicago& #39;s website:

https://oi.uchicago.edu/research/publications/oip/nippur-volume-4-early-neo-babylonian-governor%E2%80%99s-archive-nippur">https://oi.uchicago.edu/research/...

https://oi.uchicago.edu/research/publications/oip/nippur-volume-4-early-neo-babylonian-governor%E2%80%99s-archive-nippur">https://oi.uchicago.edu/research/...

This is all to say: to be certain, the only date we can give this text is as such; it was found in situ, thus we have archaeological record, and other tablets to relatively date it. Plus, DT 1 and this copy are of the near same recension. Case closed!

Or is it?

Or is it?

There are many philological aspects of this text which I argue belong to much larger and older traditions than the first quarter of the 1st millennium BCE. First up is a text first discussed by Benno Landsberger back in 1935, BM 104727.

Here& #39;s a caveat: I can& #39;t confirm this tablet. Published by Theophilus Pinches in 1904, the tablet& #39;s accession number was initially 1912-5-13, 2, but these numbers are attributed to a Nabonidus cylinder; this is where I trust Grayson and Brinkman.

A portion of the tablet reads:

A portion of the tablet reads:

12′. …the old [tabl]et – the kings, the ancestors…

13’. …with whomever we have considered it. The words of…

14’. …toward Nippur, the city of Sippar or Babyl[on

15’. …and a nobody, a stranger, his son and rulers…

16’. …rival of his kingship he will sho[w?

13’. …with whomever we have considered it. The words of…

14’. …toward Nippur, the city of Sippar or Babyl[on

15’. …and a nobody, a stranger, his son and rulers…

16’. …rival of his kingship he will sho[w?

Line 14 stuck out to Landsberger because it concerns the three cities discussed in šarru ana dīnim lā iqūl; in DT 1, lines 9 onward deal with repercussions against the king should he mess with the cities of Sippar, Nippur, and Babylon. In that order.

An example looks like this:

"If the king has coerced a citizen of Sippar, Nippur, or Babylon to enter prison – regarding that place one was coerced: the city will be laid down to the foundation; a foreign enemy will enter in" (DT 1: 19-22).

But wait, there& #39;s more!

"If the king has coerced a citizen of Sippar, Nippur, or Babylon to enter prison – regarding that place one was coerced: the city will be laid down to the foundation; a foreign enemy will enter in" (DT 1: 19-22).

But wait, there& #39;s more!

This line, also in our Nippur copy, actually has the cities arranged differently, matching that of 104727: "If the king has coerced a citizen of Nippur, Sippar, or Babylon to enter prison..."

While this doesn& #39;t mean we are looking at the same tablet, we should linger here a bit.

While this doesn& #39;t mean we are looking at the same tablet, we should linger here a bit.

The phenomenon of city alliances aren& #39;t well known outside of the first millennium. This Middle Babylonian text, which I date to the 12th century BCE, suggests that we have a tradition found in the 8th century that has lasted for at least 400 years.

Kathryn Slanski noted surprising similarity to the language shared between šarru ana dīnim lā iqūl and a kudurru dating to Meli-šihu, also early 12th century:

“I did not impose for ilku-service the ones set for exemption and that which is written upon his narû..."

“I did not impose for ilku-service the ones set for exemption and that which is written upon his narû..."

Compare:

"If the king has levied together Sippar, Nippur, and Babylon, and imposed servitude on those forces through ilku-service" (DT 1 23-25)

"Should the king undo their treaty and change their narû to have them go on campaign (or) count them for duty" (DT 1 51-52)

"If the king has levied together Sippar, Nippur, and Babylon, and imposed servitude on those forces through ilku-service" (DT 1 23-25)

"Should the king undo their treaty and change their narû to have them go on campaign (or) count them for duty" (DT 1 51-52)

There& #39;s enough here to make the suggestion that we can pull back the living tradition embedded within šarru ana dīnim lā iqūl to at least the 12th century, but we can also be a bit more precise thanks to the famous king Nebuchadnezzar (not the biblical one).

During the famous campaign to bring Marduk back to Babylon from his vacation in Elam, Nebuchadnezzar levied troops from three cities in particular: Nippur, Sippar, and Babylon. During their campaign he "did not give water to drink or allow them to recover from their fatigue."

This massive event that occurred at the end of the 12th century inspired the writing of the Enuma Elish, Lambert argues.

Because šarru ana dīnim lā iqūl is concerned about the levying of troops in these cities (DT 1 35-37), I think Nabuchadnezzar is being channeled here.

Because šarru ana dīnim lā iqūl is concerned about the levying of troops in these cities (DT 1 35-37), I think Nabuchadnezzar is being channeled here.

Thus, this text most likely belongs between the 11th through the 9th centuries, wherein city dynamics swing toward Babylon, Borsippa and Kutha.

tl; dr: šarru ana dīnim lā iqūl& #39;s dating is between 11th - 9th century BCE, canonized around the 8th century.

Thank you!

tl; dr: šarru ana dīnim lā iqūl& #39;s dating is between 11th - 9th century BCE, canonized around the 8th century.

Thank you!

Not featured in this thread: discourse on kidinnūtu, discussion of wisdom versus Realpolitik, the use of this text against King Esarhaddon (SAA 18, 124) and majority nuances that simply are lost in trying to write 280 character posts.

That all will be published in due time!

That all will be published in due time!

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter