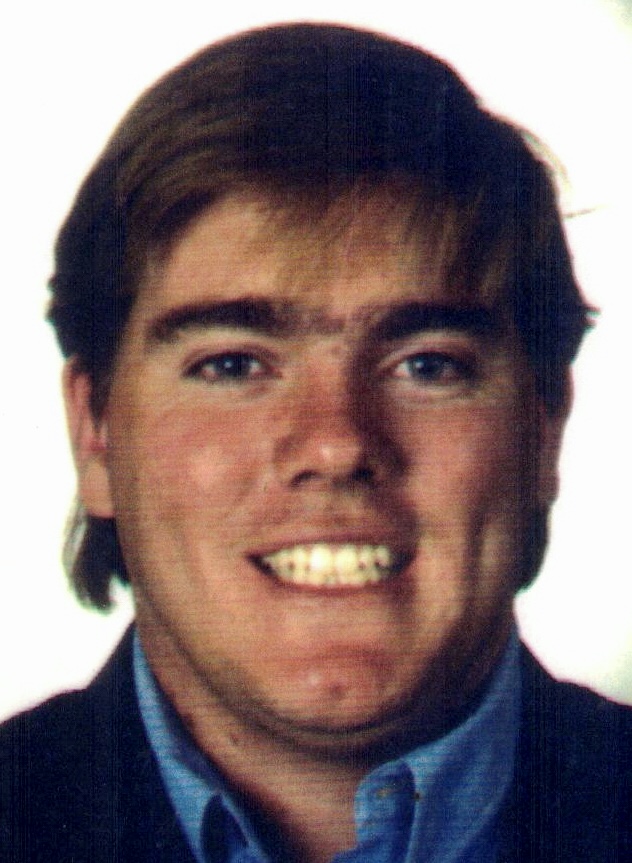

It’s my brother’s birthday. He was born in 1970, 50 years ago, on a Monday like today.

He counts on me to embarrass us on such occasions. So, I’ve put together a thing.

A thread about jerks. And acceptance.

He counts on me to embarrass us on such occasions. So, I’ve put together a thing.

A thread about jerks. And acceptance.

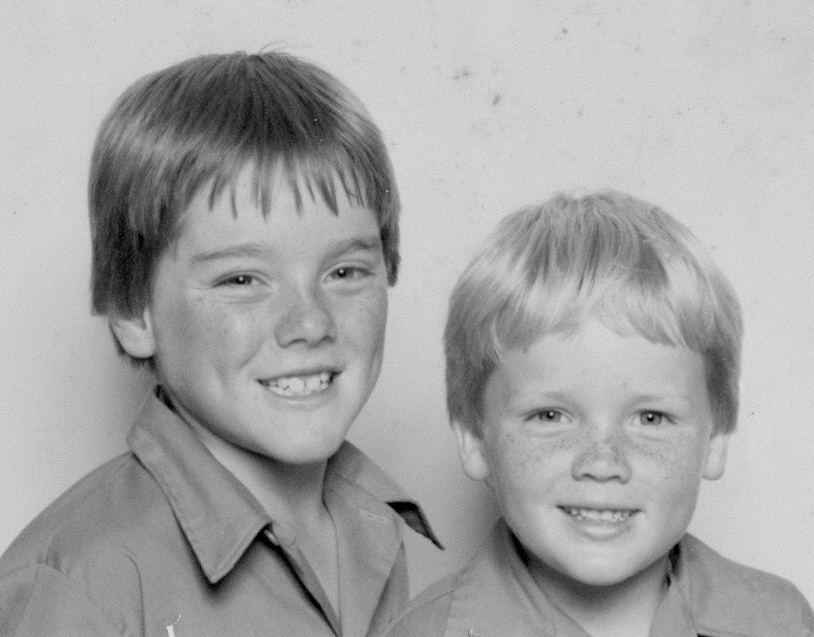

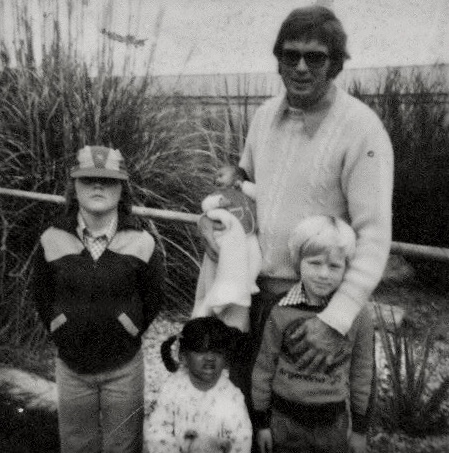

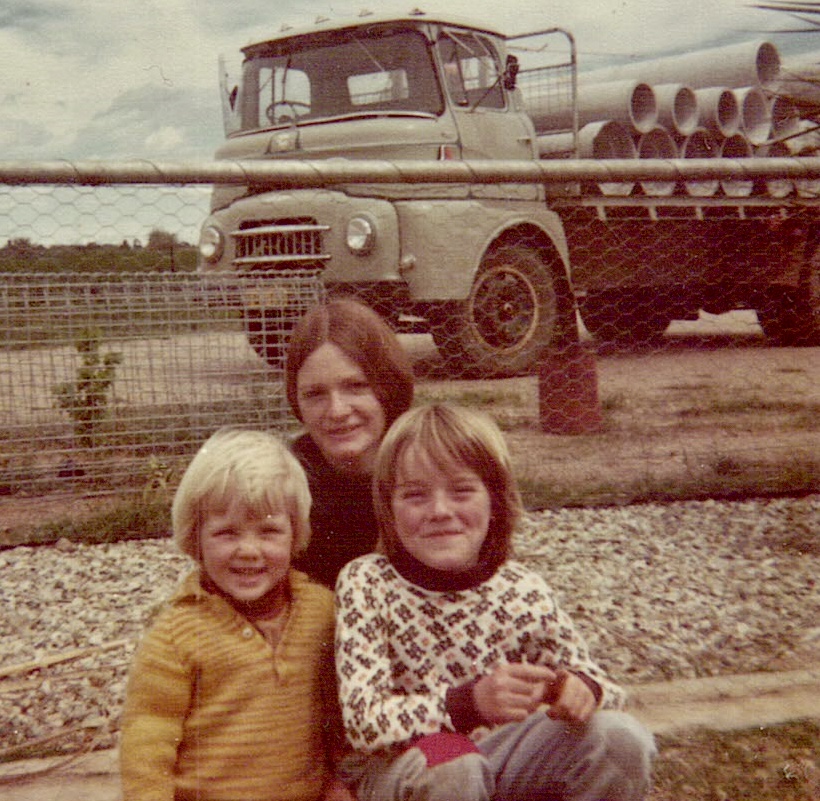

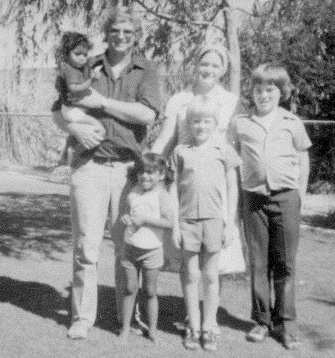

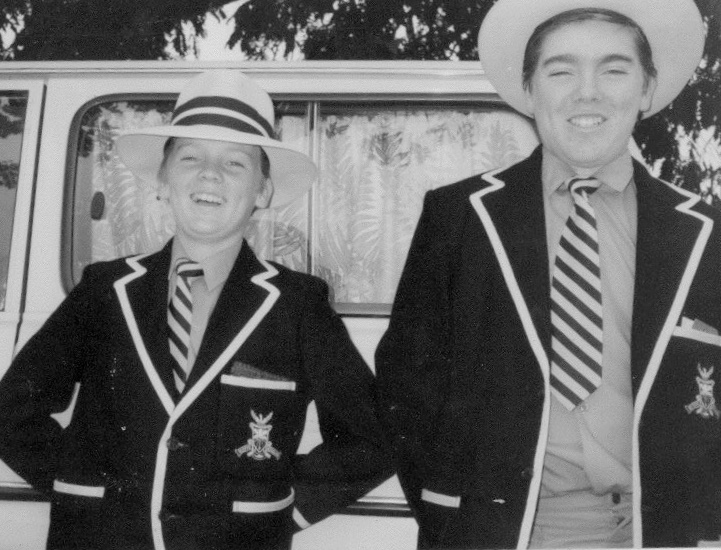

I’m told we were once mates. Inseparable. But I can’t recall a time we weren’t trying to kill each other. He had the edge – two years and 10 kilos – but I was a clever little shit skilled at guerrilla war. The old hit-and-run, hide-behind-mum trick. No wonder he disliked me.

I’ve got scars on my face (hit with a rock, pushed into a fence), my foot has a lump where it broke in three places (tripped playing soccer), and I can still feel about 900 cricket balls drilling my thigh, ribs or cranium in the nets. That maniac giggled every time.

Once, both aged under 10, dad tried reverse psyche to get us to stop scrapping. He bought tiny boxing gloves and had us fight three rounds on the lawn. I covered up, timid, until cyclone Vince ran out of puff, then landed a single lucky punch on the bell, knocking him out. Yass!

My euphoria lasted until the ‘bonus’ fourth round. Dad coached Vinny back onto his feet to exploit my newfound swagger, and he thumped me – KO followed by TKO. The gloves were hung on a wall as a reminder and we never punched-on again, mutually cautious.

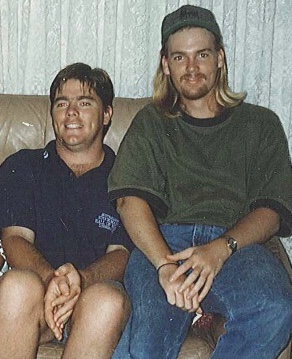

We grew further apart at boarding school – homesick boys able to witness but not fix each other’s problems. Then uni in the city for me while he went home to the farm. We had nothing in common. When we did talk, I showed off. But in our 20s we found ourselves sharing a house.

Easy-going is how people describe Vincent. But I’ll tell you a secret – he was angry. It was buried deep, maybe only allowed out with me. Likely he thought I was a jerk. But also, maybe it was safe to be mad at me, to show me his bad side.

We tried hard to be good boys.

We tried hard to be good boys.

Back then, he liked INXS. The Cars. Springsteen. Loud songs by guys not afraid to be themselves. The more dutiful son, he was a Christian like our parents. It pleased them and gave him some peace. But with me there was always a brooding rage asking for an excuse.

He had plans. He was finishing an apprenticeship. He was getting married. It was coming together. He hadn’t chosen his best man, but I wanted the job. I figured he had better options, and I was braced for indignity. But then, at 24, he got sick.

A stomach-ache. Cancer. He died a month later and we buried him in Cairns. My parents reserved plots on either side, protective, longing to join him in heaven. I stop by for a chat when I’m in town, which is less often these days.

In time, I became an atheist.

In time, I became an atheist.

Alone in hospital, near the end, he asked ‘why me, Anew?’ Caught off guard by his vulnerability, the childhood nickname, I said ‘cause you’re the one strong enough to beat this, Bince’. I was trying to comfort him, to fix it, but it felt hollow. It‘s the last exchange I recall.

I wish I’d told him: I don’t know, Vincent. It’s completely fucking unfair. You’ve done nothing to deserve this. I’m so angry and upset this is happening. I want you to be free of it. I wish I could help, and I don’t know how. But I won’t leave you to suffer it alone.

I delivered his eulogy, a naive 22-year-old trying to shoulder the sadness of everyone around me.

I lionised him. Idealised him. Mythologised him. Still trying to be his best man.

Today, I honour him with the messier truth of who he was to me, who he allowed me to see.

I lionised him. Idealised him. Mythologised him. Still trying to be his best man.

Today, I honour him with the messier truth of who he was to me, who he allowed me to see.

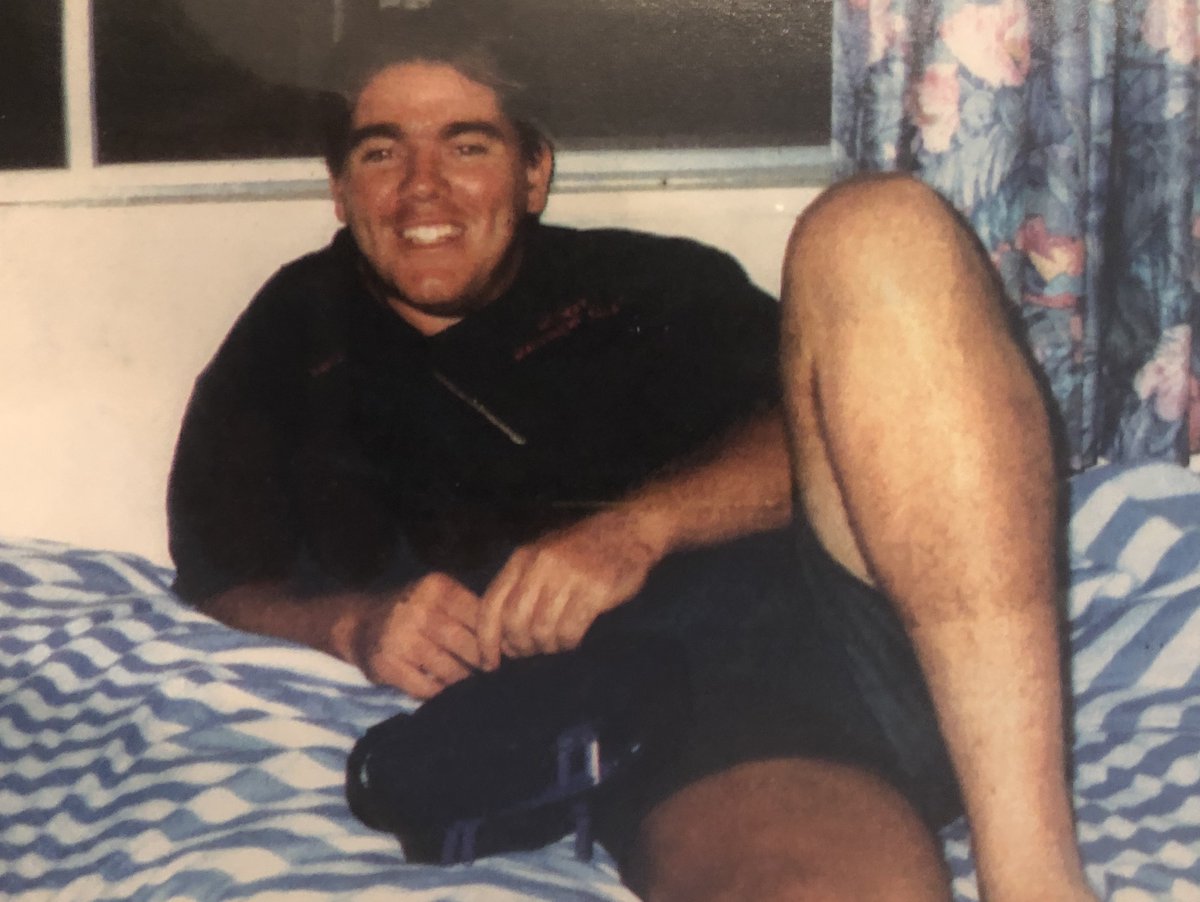

He was charming, but unaware of it. He had a loud, infectious laugh. A natural smile. Dimples that girls often liked. Eyebrows that he didn’t. A left arm that should have been licensed. A propensity to drop farts that could clear a room.

He was dependably kind, honest, decent.

He was dependably kind, honest, decent.

He struggled at school. He got held back a year. He was bullied for being quiet and slow by smart-arses who knew the shy, gentle oaf would never hit back, until one day he did.

That was a good day.

That was a good day.

He wanted my confidence. I wanted his forearms. When we were little, he’d make me answer the door, the phone. In a store, he’d give me the thing he wanted, then lift me at the counter to pay for it.

He was my big brother, but I felt above him. Better.

I felt sorry for him.

He was my big brother, but I felt above him. Better.

I felt sorry for him.

I started missing him about five years ago. I’d find myself suddenly thinking of him, and... tears. It made no sense. We weren’t even friends, right? It had been 20 years.

I avoided it. Instead, I ran away and blew up my life.

But grief is a patient teacher.

I avoided it. Instead, I ran away and blew up my life.

But grief is a patient teacher.

I pursued change for the wrong reasons, went about it the wrong way, failed, and hurt people.

Mired in pain I couldn& #39;t fix, I felt worthless, bitter, foolish.

Heartbroken.

A total jerk.

I had to learn to accept it all, grieve, and love me anyway. Perhaps for the first time.

Mired in pain I couldn& #39;t fix, I felt worthless, bitter, foolish.

Heartbroken.

A total jerk.

I had to learn to accept it all, grieve, and love me anyway. Perhaps for the first time.

Vincent led me to that place of acceptance. I couldn’t get there on my own. Missing him was about missing something in myself. Grieving for him opened me to self-compassion.

After all these years, he was still lifting me.

After all these years, he was still lifting me.

He was nobody special. He had many flaws. He didn’t like himself. He carried the fear of feeling he was not enough.

Like me.

But I loved him anyway. Because he was mine – temper, farts and all.

Because he was also unique and wonderful. My big bro.

Like me.

But I loved him anyway. Because he was mine – temper, farts and all.

Because he was also unique and wonderful. My big bro.

I’ve tried to be the best man, taking on jobs, problems, loves, to show I was enough – ignoring what others needed, served reality, or suited me. It was ignorance, ego and shame.

I regret the hurt caused by my immaturity. I’ve made changes. I try now simply to be dependable.

I regret the hurt caused by my immaturity. I’ve made changes. I try now simply to be dependable.

It’s been 25 years since I lost my brother. I lost me too, then found us, learning to grieve for him, for myself, and what we missed out on.

I love you, Vincent. I’d give anything – another scar, the other leg – to have you back.

Wherever you are, you are also in my heart.

I love you, Vincent. I’d give anything – another scar, the other leg – to have you back.

Wherever you are, you are also in my heart.

Happy birthday, Vincent Owen John Webster.

11/5/1970 – 17/4/1995.

Thanks for everything you did for me, Bince. Rest in peace, ya big jerk https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🏏" title="Cricket bat and ball" aria-label="Emoji: Cricket bat and ball">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🏏" title="Cricket bat and ball" aria-label="Emoji: Cricket bat and ball"> https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🥊" title="Boxing glove" aria-label="Emoji: Boxing glove">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🥊" title="Boxing glove" aria-label="Emoji: Boxing glove"> https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="❤️" title="Red heart" aria-label="Emoji: Red heart">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="❤️" title="Red heart" aria-label="Emoji: Red heart">

11/5/1970 – 17/4/1995.

Thanks for everything you did for me, Bince. Rest in peace, ya big jerk

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🥊" title="Boxing glove" aria-label="Emoji: Boxing glove">https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="❤️" title="Red heart" aria-label="Emoji: Red heart">" title="Happy birthday, Vincent Owen John Webster. 11/5/1970 – 17/4/1995.Thanks for everything you did for me, Bince. Rest in peace, ya big jerk https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🏏" title="Cricket bat and ball" aria-label="Emoji: Cricket bat and ball">https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🥊" title="Boxing glove" aria-label="Emoji: Boxing glove">https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="❤️" title="Red heart" aria-label="Emoji: Red heart">">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🥊" title="Boxing glove" aria-label="Emoji: Boxing glove">https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="❤️" title="Red heart" aria-label="Emoji: Red heart">" title="Happy birthday, Vincent Owen John Webster. 11/5/1970 – 17/4/1995.Thanks for everything you did for me, Bince. Rest in peace, ya big jerk https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🏏" title="Cricket bat and ball" aria-label="Emoji: Cricket bat and ball">https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🥊" title="Boxing glove" aria-label="Emoji: Boxing glove">https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="❤️" title="Red heart" aria-label="Emoji: Red heart">">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🥊" title="Boxing glove" aria-label="Emoji: Boxing glove">https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="❤️" title="Red heart" aria-label="Emoji: Red heart">" title="Happy birthday, Vincent Owen John Webster. 11/5/1970 – 17/4/1995.Thanks for everything you did for me, Bince. Rest in peace, ya big jerk https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🏏" title="Cricket bat and ball" aria-label="Emoji: Cricket bat and ball">https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🥊" title="Boxing glove" aria-label="Emoji: Boxing glove">https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="❤️" title="Red heart" aria-label="Emoji: Red heart">">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🥊" title="Boxing glove" aria-label="Emoji: Boxing glove">https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="❤️" title="Red heart" aria-label="Emoji: Red heart">" title="Happy birthday, Vincent Owen John Webster. 11/5/1970 – 17/4/1995.Thanks for everything you did for me, Bince. Rest in peace, ya big jerk https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🏏" title="Cricket bat and ball" aria-label="Emoji: Cricket bat and ball">https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🥊" title="Boxing glove" aria-label="Emoji: Boxing glove">https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="❤️" title="Red heart" aria-label="Emoji: Red heart">">