1. Happy Mother& #39;s Day. For the past two weeks, I turned my attention to the extreme measures paramedics have been forced to take in the coronavirus hot zone, where some units have instituted a no-CPR rule in an effort to protect their first responders https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/10/nyregion/paramedics-cpr-coronavirus.html">https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/1...

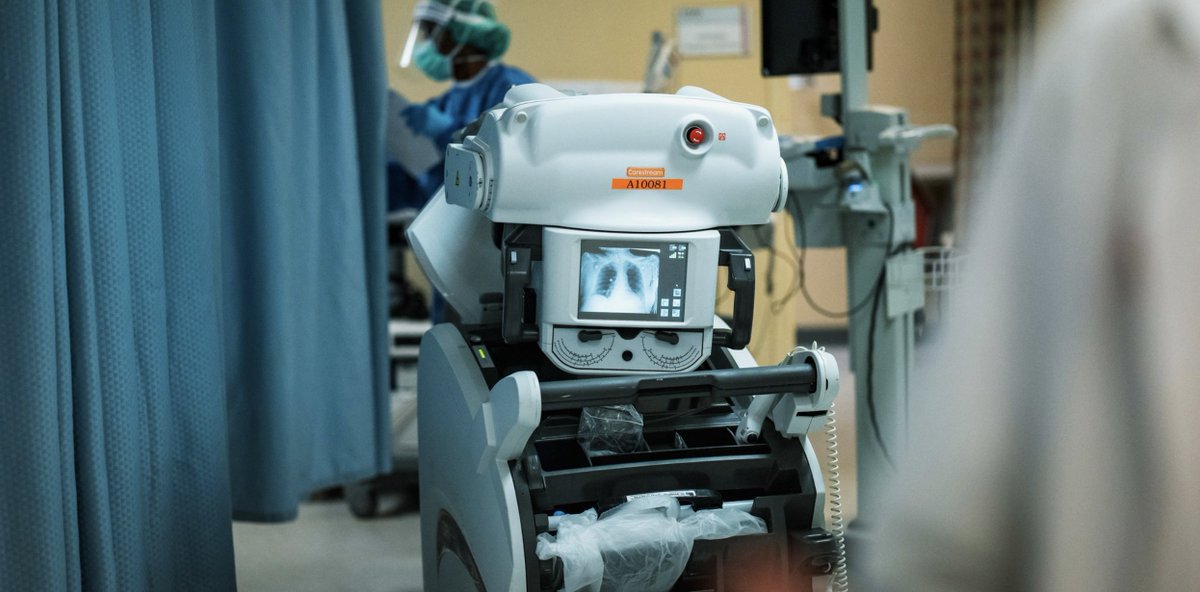

2. Along with @rcjonesphoto, I embedded with the ambulance crews shuttling patients to @UnivHospNewark in Newark, one of the hardest-hit areas in the country. Seven of the hospital& #39;s employees have died of Covid and 1/5th of its 270 first responders are out sick or in quarantine

3. At one point, the hospital came close to buckling, with not enough staff to tend to the dozens of patients lining the halls of the ER in gurneys: https://twitter.com/ShereefElnahal/status/1246853880056614914?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed%7Ctwterm%5E1246853880056614914&ref_url=https%3A%2F%2Fscoop.nyt.net%2Fui%2Foakarticle%2F100000007130502%2Fweb%2Fediting">https://twitter.com/ShereefEl...

4. It was clear that something needed to be done to better protect their frontline workers, and after multiple conference calls, Terry Hoben, the coordinator of the hospital& #39;s emergency medical service decided to take measures to limit the exposure of his first responders.

5. The riskiest procedures are those that cause the virus to be aerosalized. That includes intubating and bagging patients. But possibly most dangerous? CPR, because chest compressions cause the lungs to inflate/deflate, shoving the virus& #39; microscopic particles into the air.

6. Here& #39;s where I learned something unexpected: As an obsessive watcher of @GreysABC, I thought that CPR goes the way it does on the show: A person goes into cardiac arrest; heroic first responders start compressions hard and fast, and more often than not, the person comes back

7. Spoiler alert: It& #39;s nothing like that in real life, to the point that studies have shown that medical dramas, where on average 70% of patients are revived, are creating a disconnect with the public. Overall only 37% of victims are brought back with CPR: https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2015/08/150828135219.htm">https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/...

8. There& #39;s a sub-category of patients for whom CPR does almost nothing: Those who have a cardiac arrest and who are found in a state called "asystole," which is basically a flat line on the EKG monitor. Even after extensive CPR, only 1 to 3% survive: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25110246 ">https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25...

9. If the person has Covid and goes into cardiac arrest, they& #39;re likely at the end stage of the disease, when the viral load is highest. The dilemma for first responders is does it make sense to do a risky procedure - CPR - on a patient whose chances of survival are under 3%?

10. In April, New York led the way in instituting a no-CPR rule for patients who had flatlined, only to cancel the policy a few days later, both because call volumes had dropped and due to public critique: https://www.nycremsco.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/2020-10-REMAC-Advisory-UPDATED-Temporary-Cardiac-Arrest-Standards-for-Disaster-Response.pdf">https://www.nycremsco.org/wp-conten...

11. Meanwhile in New Jersey, a majority of its 22 advanced life support units have instituted some form of restrictions on CPR for patients who have flatlined. The calculation makes sense: Why risk the health of first responders for a risky procedure that almost never works?

12. But here& #39;s the tension I discovered: First responders I interviewed in New Jersey, including paramedic Lisa Kahle who got sick with Covid, were conflicted by the new policy. They say it goes against the ethos of their profession of doing everything they can to save every life

13. The @UnivHospNewark no-CPR policy went into effect on April 11. As my story went to print today, there& #39;s already talk of rescinding it. As their chief paramedic Terry Hoben says, "if you can save 1 life for every 100, it& #39;s still worth it."

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter