Economic Naturalist Question # 11. Why are the least productive workers in a firm typically paid more than the economic value of what they produce, while the most productive workers are paid less? #EconTwitter

The theory of competitive labor markets suggests that workers will be paid in accordance with the value of what they add to their employer’s bottom line. Yet in most organizations, the contributions of workers doing similar work differ by much more than the wages they are paid.

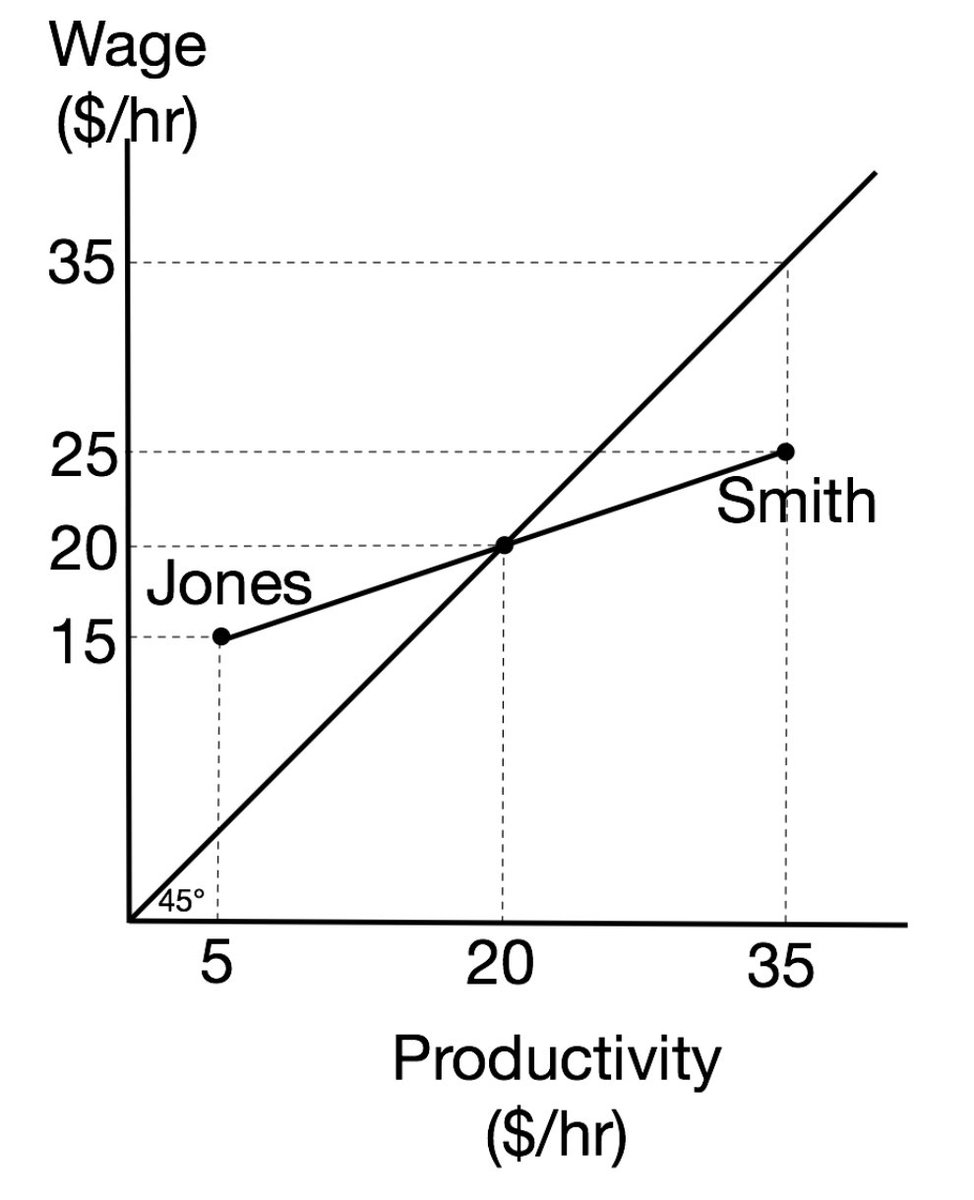

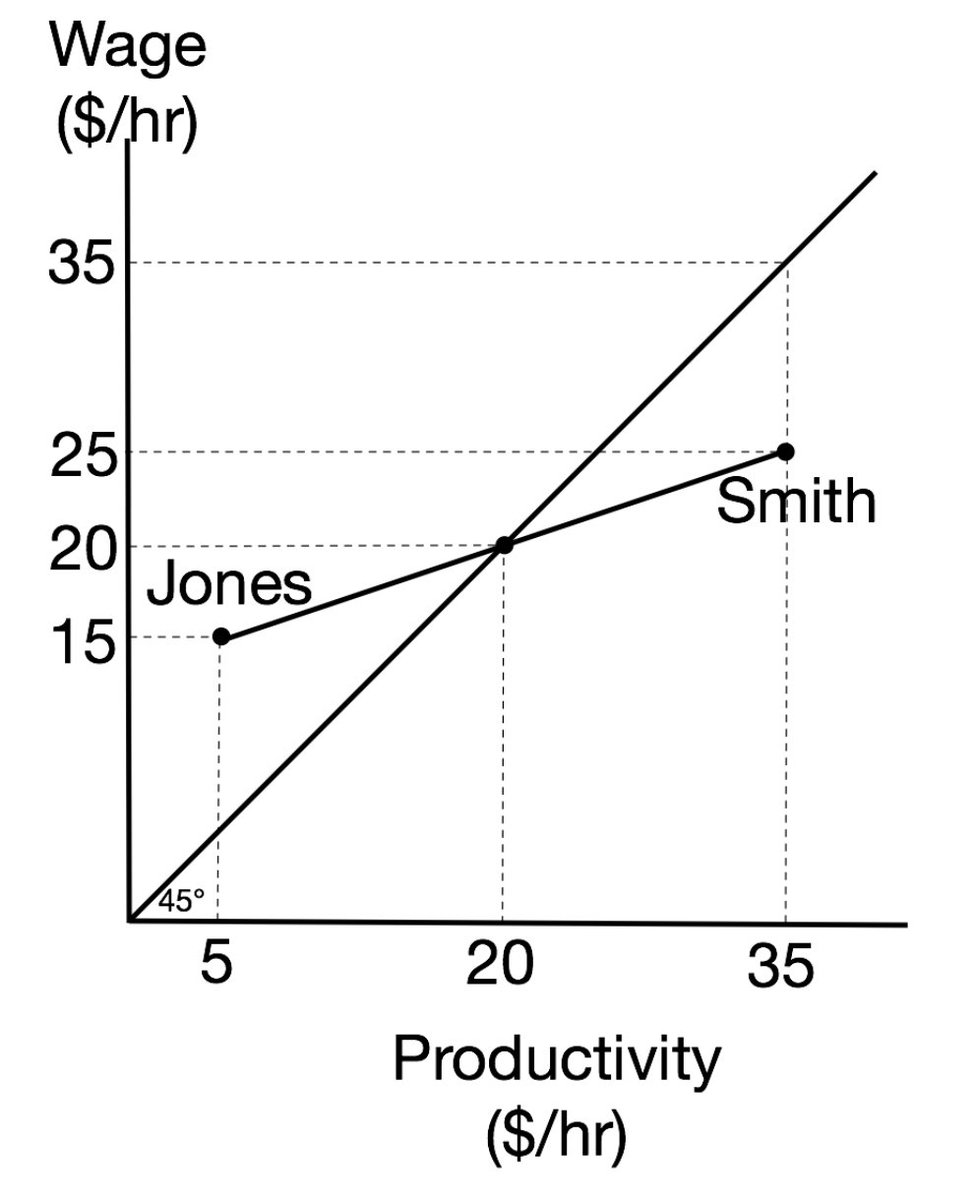

For instance, if Smith and Jones are carpenters and Smith contributes $35/hr to his employer’s bottom line while Jones contributes only $5/hr, theory predicts that the two would be paid $35/hr and $5/hr, respectively.

In practice however, observed wages differ much less than observed productivity differences. Smith might be paid only $25/hr, for example, while Jones might be paid $15/hr.

More generally, the top-ranked workers within a group are paid less in proportion to what they contribute, while the bottom-ranked workers are paid more. This seems like a good deal for the bottom-ranked workers!

But this pattern also seems to imply cash on the table. If Smith is worth $35/hr and is being paid only $25/hr, then a rival firm could pocket a quick $5/hr in extra profits by luring him away at a salary of $30/hr.

But this would still leave cash on the table for other rival firms. So Smith’s salary should be quickly bid up to $35/hr, if that’s indeed the value of what he contributes. Yet that generally doesn’t happen.

A possible explanation begins with the assumption that most workers would prefer to occupy high-ranked positions in their work groups rather than low-ranked ones.

The problem is that not every worker’s preference for a high-ranked position can be satisfied within any given work group. After all, 50 percent of the positions in the group must always be in the bottom half.

So the only way some workers are able to enjoy the satisfaction inherent in positions of high rank is if others are willing to endure the dissatisfactions associated with low rank.

If workers cannot be forced to remain with an organization against their wishes, then low-ranked workers will find it attractive to remain only if they receive additional compensation.

Where does this extra compensation come from? It appears to be financed by an implicit tax on the earnings of their high-ranked coworkers.

If the tax isn’t too high, the high-ranked workers are happy to remain with the firm, even though they could earn more elsewhere, and the low-ranked workers find the extra pay sufficient to compensate for the burdens of low rank.

The resulting pay pattern within each firm is thus the functional equivalent of a progressive income tax.

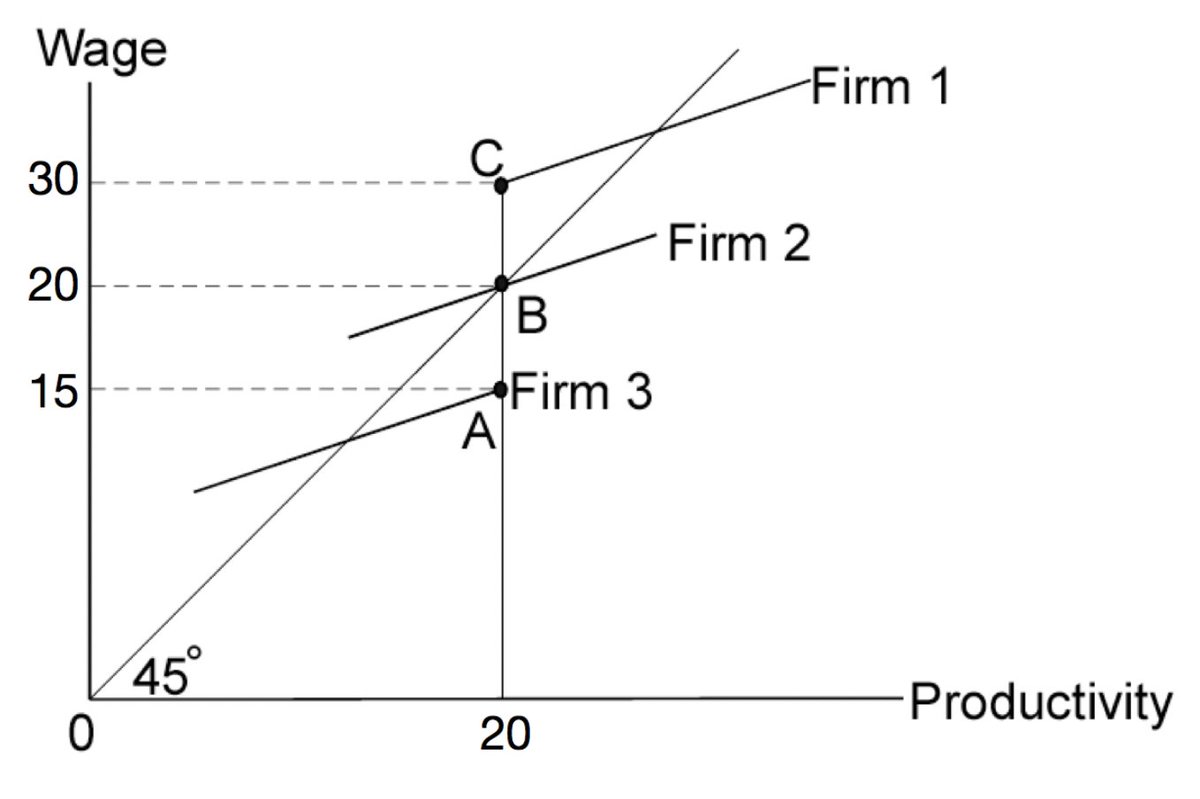

In many occupations, individuals face a menu of job choices in different firms. Those who don’t care much about high local rank do best by accepting low-ranked positions at premium pay in firms with highly productive employees—positions like C in Firm 1 in the diagram.

In contrast, those who care a lot about high local rank do best by accepting positions like A in Firm 3, which has low average productivity. Those who assign intermediate value to having high local rank are more likely to choose mid-ranked positions like B at firm 3.

Absent wage premiums for occupying positions of low local rank, those holding such positions would find it attractive to move to firms that employed only workers like themselves. Firms would tend to fragment into units with little variance in individual productivity.

Relative to an alternative in which equally productive workers were paid the value of what they produced, the observed pay structure benefits everyone by enabling workers to buy or sell positions in their local productivity distributions at mutually attractive implicit prices.

Those in top slots get high rank that they value more than they paid for it. And those in bottom slots receive compensation that exceeds their perceived costs of having low rank. But the observed pay structure not only efficient, it is also fair.

That’s because those who enjoy the benefits of high-ranked positions, which could not exist in the absence of low-ranked positions, must compensate the occupants of low-ranked positions by enough to secure their agreement to bear whatever costs are associated with low rank.

As within firms, high-ranked positions in society at large cannot exist unless others occupy positions of low rank. This may help explain why the tax systems in most societies closely mimic the progressive reward patterns implicit in the pay schedules of competitive firms.

Viewed in this light, progressive taxation does not violate the property rights of top earners. On the contrary, large and diverse populations would find it difficult to achieve the social cohesion necessary to function effectively in its absence.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter