During the 1918 flu pandemic, Wisconsin was the only state to take uniform, statewide shutdown measures, which historians credit with limiting deaths. But some cities reopened early — with deadly results.

A look at what we can learn from that history. https://www.wisconsinwatch.org/2020/04/wisconsins-pandemic-past-offers-clues-to-its-coronavirus-future/">https://www.wisconsinwatch.org/2020/04/w...

A look at what we can learn from that history. https://www.wisconsinwatch.org/2020/04/wisconsins-pandemic-past-offers-clues-to-its-coronavirus-future/">https://www.wisconsinwatch.org/2020/04/w...

No doubt, a lot has changed since 1918. But in reporting this piece, I was struck by the many uncanny parallels between Wisconsin& #39;s response to the 1918 pandemic — and how residents talked about it — and today& #39;s COVID-19 crisis.

The century-old newspapers gave me goosebumps.

The century-old newspapers gave me goosebumps.

On Oct. 10, 1918, Dr. Cornelius Harper, Wisconsin& #39;s health chief, used his extraordinary power to shutter schools & public gatherings statewide. Some Wis. cities had already closed (as had some in other states). But Wisconsin was alone in taking such a sweeping statewide action

Save for a few hiccups, residents swiftly complied. Even local businessmen who would lose lots of money — like these movie house owners in Oshkosh — said they understood the public health needs.

(This from Oshkosh& #39;s local debate, just before Wisconsin closed statewide.)

(This from Oshkosh& #39;s local debate, just before Wisconsin closed statewide.)

It was easy to find examples like this. The 1918 pandemic struck at a time when Wisconsinites held widespread faith in government, and patriotism meant following the directives of public officials, historians told @wisconsinwatch.

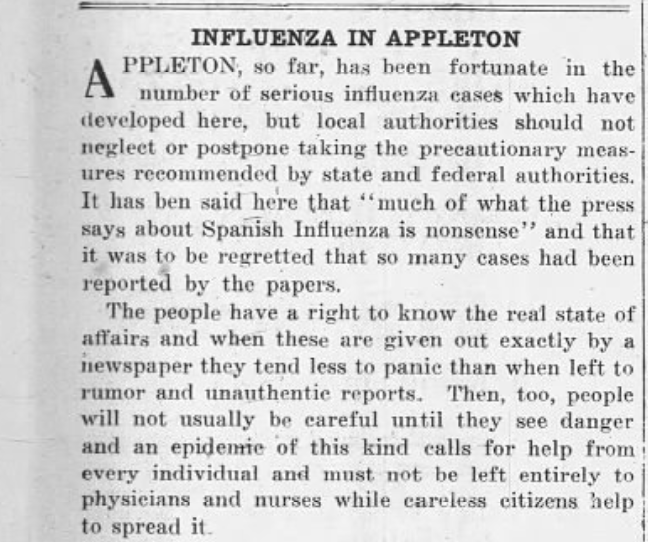

That& #39;s not to say there was no dissent. On Oct. 14, 1918, staffers at the Appleton Evening Crescent, for instance, lamented those who, more or less, accused the newspaper of spreading fake news — as bodied piled up in Philadelphia.

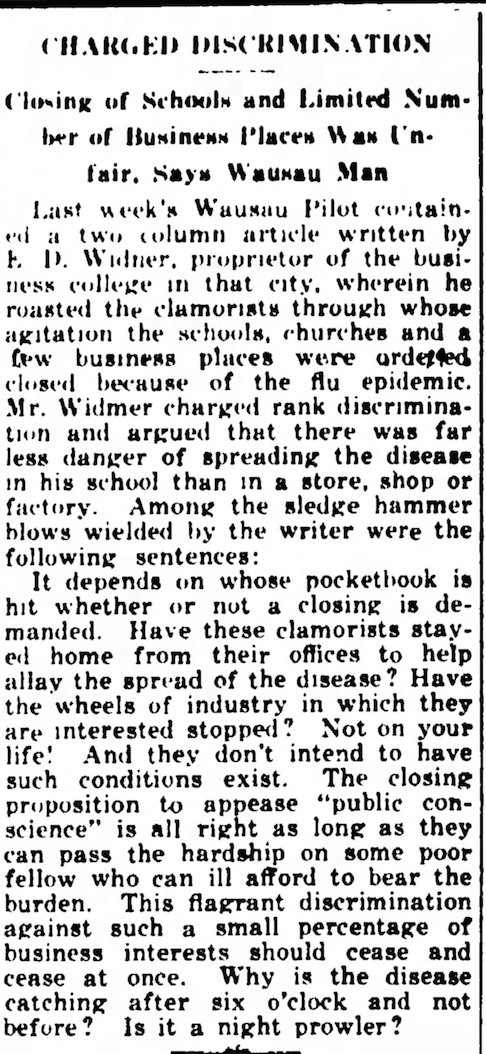

Or like on Christmas 1918, when the Gazette of Stevens Point printed this opinion:

"The closing proposition to appease "public conscience" is all right as long as they can pass the hardship on some poor fellow who can ill afford bear the burden."

"The closing proposition to appease "public conscience" is all right as long as they can pass the hardship on some poor fellow who can ill afford bear the burden."

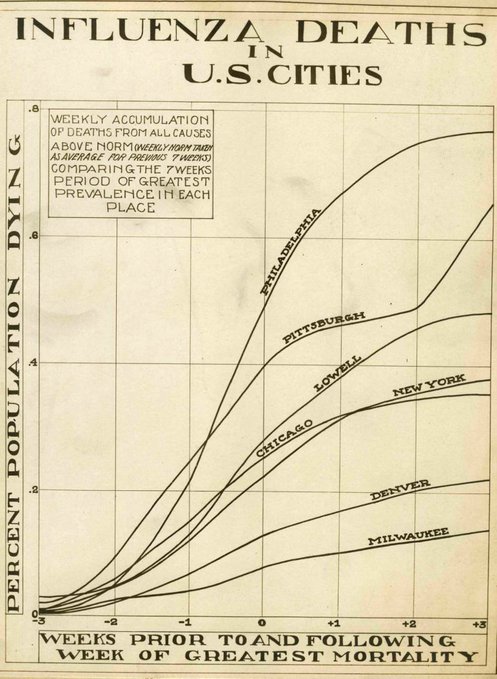

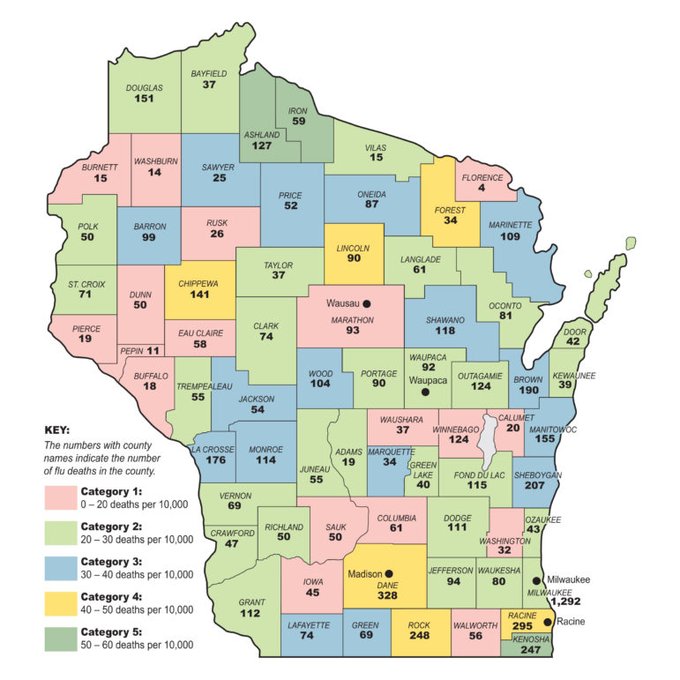

The (misnamed) Spanish flu would ultimately kill 8,459 and sicken 103,000 of Wisconsin& #39;s 2.6 million residents at the time. But historians say the relatively early statewide action limited deaths from a disease that killed 675,000 nationally.

And Milwaukee was seen as having one of the most effective responses from big U.S. cities, even though Milwaukee County still recorded 1,292 deaths during the 1918 pandemic.

BUT...

Pockets of 1918 Wisconsin offer examples of a warning we& #39;re hearing today: That a virus with no vaccine or cure might hit in waves, meaning that reopening too quickly can generate new hotspots in communities that thought they were safe.

Pockets of 1918 Wisconsin offer examples of a warning we& #39;re hearing today: That a virus with no vaccine or cure might hit in waves, meaning that reopening too quickly can generate new hotspots in communities that thought they were safe.

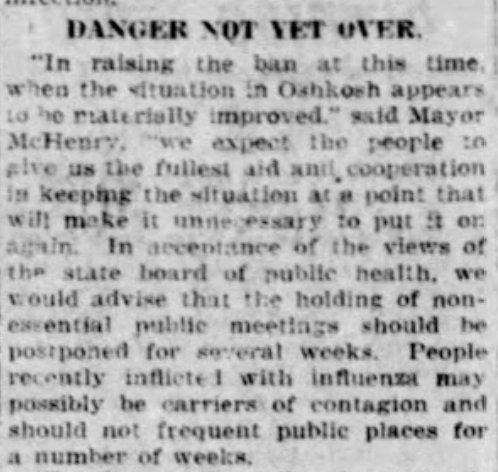

Take Oshkosh, which which reopened on Nov. 4, 1918 after the state allowed local governments to decide when to do so. Mayor Arthur C. McHenry warned that the state was not out of the woods.

But...

But...

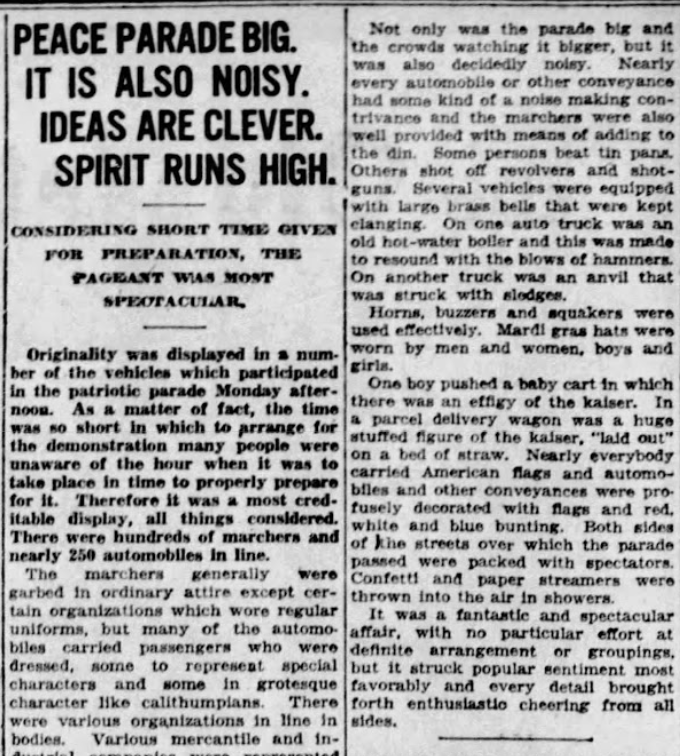

McHenry and everyone else quickly forgot those words *just one week later* once news spread of peace with Germany.

There were drums! Fifes! Bells! Buzzes! Men striking an anvil with sledges (!) as people flooded previously empty streets.

McHenry joined with city employees.

There were drums! Fifes! Bells! Buzzes! Men striking an anvil with sledges (!) as people flooded previously empty streets.

McHenry joined with city employees.

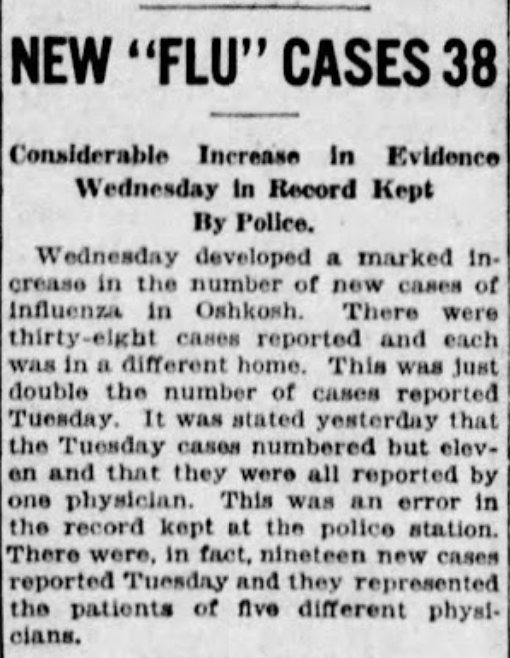

And just days later, a surge in flu cases, and Oshkosh once again shut its schools and public gatherings. It wouldn& #39;t reopen schools until Dec. 3, with a ban on sniffling students.

The town of roughly 30K would report a total of 2,083 flu cases by Dec. 11.

The town of roughly 30K would report a total of 2,083 flu cases by Dec. 11.

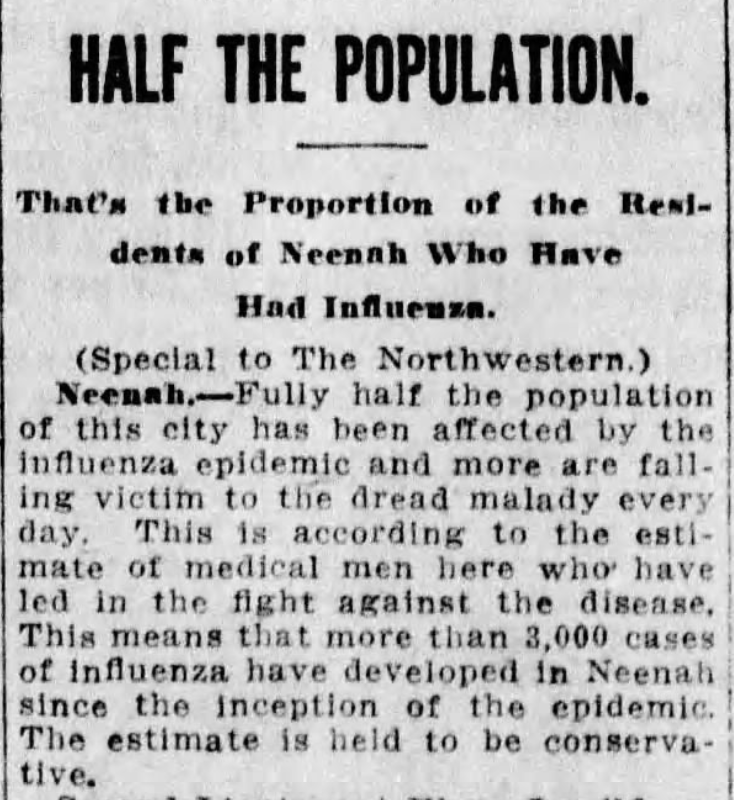

Nearby Neenah followed a similar path, holding a big parade. A month later, the Daily Northwestern reported that “fully half the population” of Neenah was touched by the flu.

Lots more detail in our full story here: https://www.wisconsinwatch.org/2020/04/wisconsins-pandemic-past-and-coronavirus-future/">https://www.wisconsinwatch.org/2020/04/w...

And for a super great dive into Wisconsin& #39;s 1918 flu pandemic response, see this 2000 Wisconsin Magazine of History piece, written by historian Steven B. Burg (quoted in my story) and republished by @wiscontext: https://www.wiscontext.org/virus-shut-down-wisconsin-great-flu-pandemic-1918">https://www.wiscontext.org/virus-shu...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter