Is the corpus of ancient Arabic poetry authentic? Since the manuscript evidence is rather late, centuries after the traditional dates of composition, can we be sure that the poems are really pre-Islamic? Let’s read a few lines of Labīd’s Mu& #39;allaqah and see. ~AA, day 1 @safaitic

Labīd b. Rabīʿah (~d. 661 CE) (is said to have) authored one of the pre-Islamic masterpieces. His ode begins with a description of the landscape and abandoned campsites. The vivid imagery and references are enhanced once we view them through an epigraphic/archaeological lens. ~AA

In line 8, he describes how the torrents ‘lay bare’ the marks of the tent. The image is compared to "zubur", usually translated as ‘writing’.

"like the zubur, the pens of which renew its content”.

Most imagine a pen writing with ink on parchment or papyrus. ~AA

"like the zubur, the pens of which renew its content”.

Most imagine a pen writing with ink on parchment or papyrus. ~AA

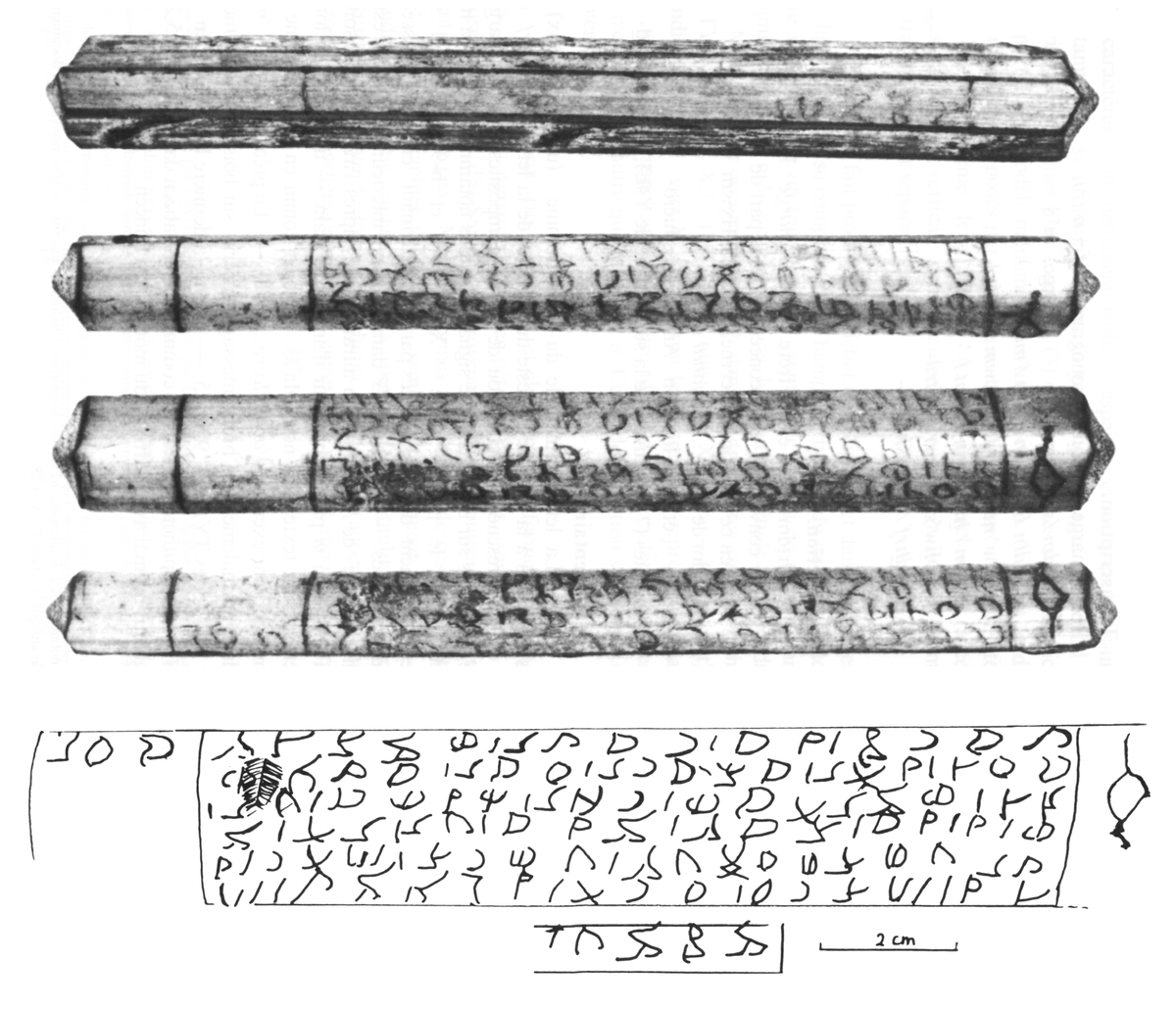

But in Ancient South Arabia, day-to-day documents were carved on wooden sticks and palm-leaf stalks with a stylus. The Sabaic verb used for this type of writing, cutting with a blade, is zbr. Islamic-period sources recognize the Yemeni origin of the root but take it as ‘book’.~AA

South Arabian zbr writing fits the context much better. The torrents carve the landscape, clearing away debris and revealing the engraved remains of the camp. The blade cutting into a zabūr document is a fantastic analogy. This method of writing continued to the 6th c. CE. ~AA

In line 10, the poet despairs at the ruins of the camp, stating:& #39;

& #39;how should we question immortal stones whose speech is unintelligible’?

Compare Labīd& #39;s line to this photo of an ancient campsite (~1st c. CE, NE Jordan), where the stones are covered in a lost script. ~AA.

& #39;how should we question immortal stones whose speech is unintelligible’?

Compare Labīd& #39;s line to this photo of an ancient campsite (~1st c. CE, NE Jordan), where the stones are covered in a lost script. ~AA.

His line implies that the stones contain knowledge about those long gone but Labīd couldn& #39;t understand them. More than ½ a millennium earlier, a man named Ḫoṭaysat son of Sakrān did the same thing, stopping at the abandoned campsite in the previous photo. ~AA.

But he could understand their language. He found the name of a loved one, Garmʾel son of Ḏeʾb, inscribed on a perimeter rock (in large letters). He wrote on the same stone:

"By Ḫoṭaysat....and he found the trace of Garmʾel (wgd ʾṯr) and said woe! (w-ql ḫbl)" ~AA.

"By Ḫoṭaysat....and he found the trace of Garmʾel (wgd ʾṯr) and said woe! (w-ql ḫbl)" ~AA.

By Labīd’s time, the language of the stones was forgotten, and with it the identity of those who were there before him. His lamentation seems to preserve a faint memory of a bygone era, when writing was an integral part of landscape and memory. See: https://twitter.com/Safaitic/status/1085540463858405377?s=20.">https://twitter.com/Safaitic/... ~AA.

Pre-Islamic mythology is found in the poems as well. One of Labīd’s famous lines ( #39):

‘Indeed, the arrows of Fate never miss their mark’

Fate = Mny is the primary adversary of the living in the pre-Islamic inscriptions (Safaitic). It lies in wait (tnẓr) like a hunter.~AA

‘Indeed, the arrows of Fate never miss their mark’

Fate = Mny is the primary adversary of the living in the pre-Islamic inscriptions (Safaitic). It lies in wait (tnẓr) like a hunter.~AA

Unlike the gods, “It can& #39;t be reasoned with. It doesn& #39;t feel pity, or remorse, or fear! And it absolutely will not stop, ever, until you are dead!” We will go into Fate on another day, but see this thread if you cant wait: https://twitter.com/Safaitic/status/1010104623934377984?s=20.">https://twitter.com/Safaitic/... ~AA

The material traditionally attributed to the pre-Islamic period is diverse and should not be treated as

a homogeneous mass. And so the question as I asked at the beginning is much too simplistic. ~AA.

a homogeneous mass. And so the question as I asked at the beginning is much too simplistic. ~AA.

But evidence of the sort I have presented does suggest that some of this material must be pre-Islamic as it preserves cultural knowledge long lost by the time medieval scholars began to write commentaries. ~AA.

Bibliography

Photo of Zabur txt: http://dasi.cnr.it/index.php?id=30&prjId=1&corId=0&colId=0&navId=599501291&recId=4164&mark=04164%2C003%2C005

Landscape">https://dasi.cnr.it/index.php... photos and inscriptions from my fieldwork; details here: https://twitter.com/Safaitic/status/1149297944195141634?s=20.

Labid& #39;s">https://twitter.com/Safaitic/... poem in english: https://academic.oup.com/jss/article-abstract/6/1/97/1664545?redirectedFrom=PDF

Labid& #39;s">https://academic.oup.com/jss/artic... Arabic text: https://ar.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D9%85%D8%B9%D9%84%D9%82%D8%A9_%D9%84%D8%A8%D9%8A%D8%AF_%D8%A8%D9%86_%D8%B1%D8%A8%D9%8A%D8%B9%D8%A9">https://ar.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D9%...

Photo of Zabur txt: http://dasi.cnr.it/index.php?id=30&prjId=1&corId=0&colId=0&navId=599501291&recId=4164&mark=04164%2C003%2C005

Landscape">https://dasi.cnr.it/index.php... photos and inscriptions from my fieldwork; details here: https://twitter.com/Safaitic/status/1149297944195141634?s=20.

Labid& #39;s">https://twitter.com/Safaitic/... poem in english: https://academic.oup.com/jss/article-abstract/6/1/97/1664545?redirectedFrom=PDF

Labid& #39;s">https://academic.oup.com/jss/artic... Arabic text: https://ar.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D9%85%D8%B9%D9%84%D9%82%D8%A9_%D9%84%D8%A8%D9%8A%D8%AF_%D8%A8%D9%86_%D8%B1%D8%A8%D9%8A%D8%B9%D8%A9">https://ar.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D9%...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter