Thread: Almost 102 years ago, another worldwide pandemic hit Chicago.

We searched through almost 1,000 pages of the Chicago Tribune’s archives to compare it with today’s coronavirus crisis.

The similarities are shocking. https://www.chicagotribune.com/coronavirus/ct-opinion-flashback-1918-flu-pandemic-timeline-htmlstory.html">https://www.chicagotribune.com/coronavir...

We searched through almost 1,000 pages of the Chicago Tribune’s archives to compare it with today’s coronavirus crisis.

The similarities are shocking. https://www.chicagotribune.com/coronavirus/ct-opinion-flashback-1918-flu-pandemic-timeline-htmlstory.html">https://www.chicagotribune.com/coronavir...

The “Spanish flu” (though there is no evidence it began in Spain) sickened half a billion people.

At least 50 million people — including 675,000 in the United States and 10,000 in Chicago — were killed by this strain of the H1N1 virus.

At least 50 million people — including 675,000 in the United States and 10,000 in Chicago — were killed by this strain of the H1N1 virus.

The 1918 flu pandemic brought many of the same restrictions for the general public that we are experiencing today.

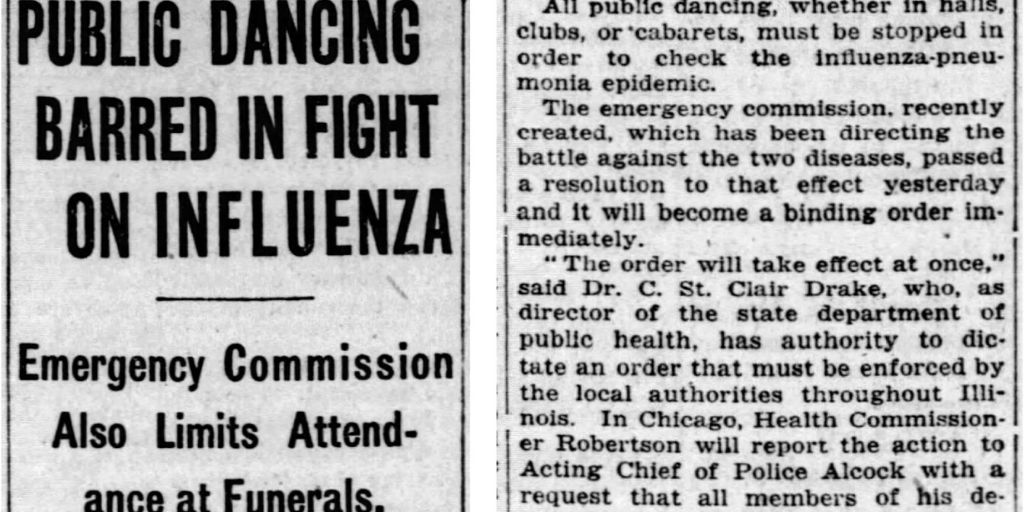

Many nonessential businesses were closed.

Funerals could only be attended by immediate family members.

And nightly dances in the city were canceled for the first time in decades.

Funerals could only be attended by immediate family members.

And nightly dances in the city were canceled for the first time in decades.

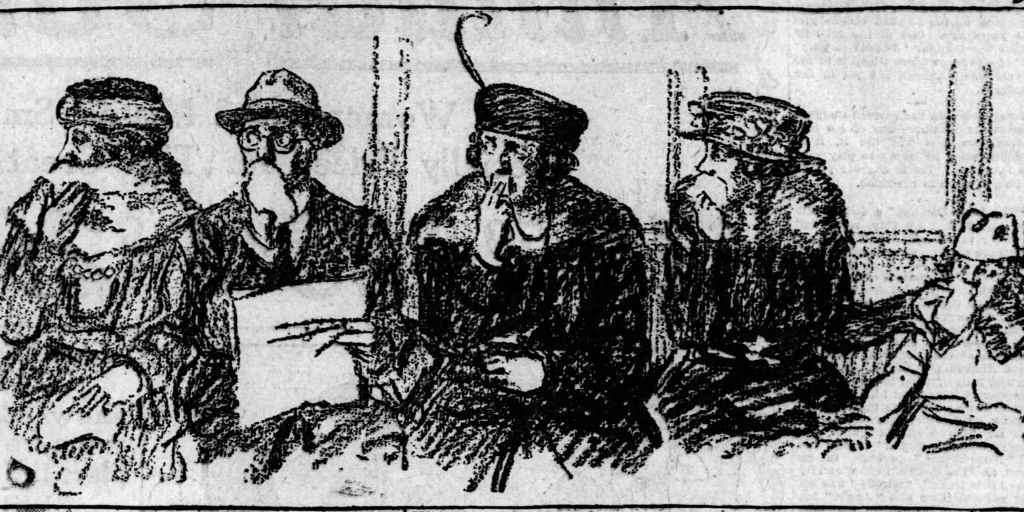

Smoking was no longer allowed on streetcar or elevated trains after the flu pandemic arrived in Chicago in September 1918.

And nervous travelers wouldn’t hesitate to stare down an errant cougher.

And nervous travelers wouldn’t hesitate to stare down an errant cougher.

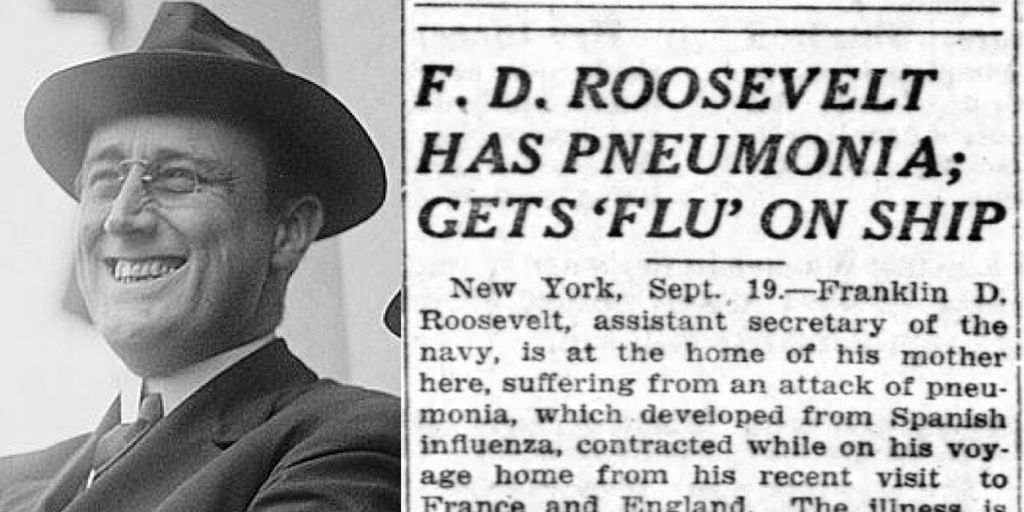

No one was immune to the virus — not the German kaiser, nor the British prime minister or a future U.S. president.

Diagnosing and caring for the sick was challenging in 1918.

Resources and staff were limited.

At the time, no test or vaccine existed and neither did breathing machines. Doctors could do little but provide supportive care.

Resources and staff were limited.

At the time, no test or vaccine existed and neither did breathing machines. Doctors could do little but provide supportive care.

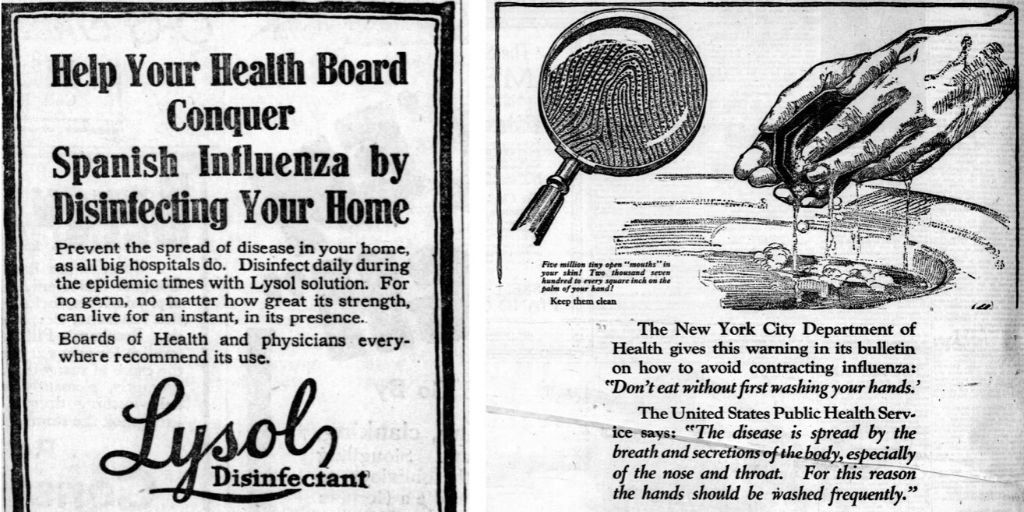

Keeping the home clean was also a concern during the 1918 flu pandemic.

Lysol was recommended by physicians for use as a disinfectant — not as an injection.

Frequent hand washing with soap was thought to stop the spread of germs.

Lysol was recommended by physicians for use as a disinfectant — not as an injection.

Frequent hand washing with soap was thought to stop the spread of germs.

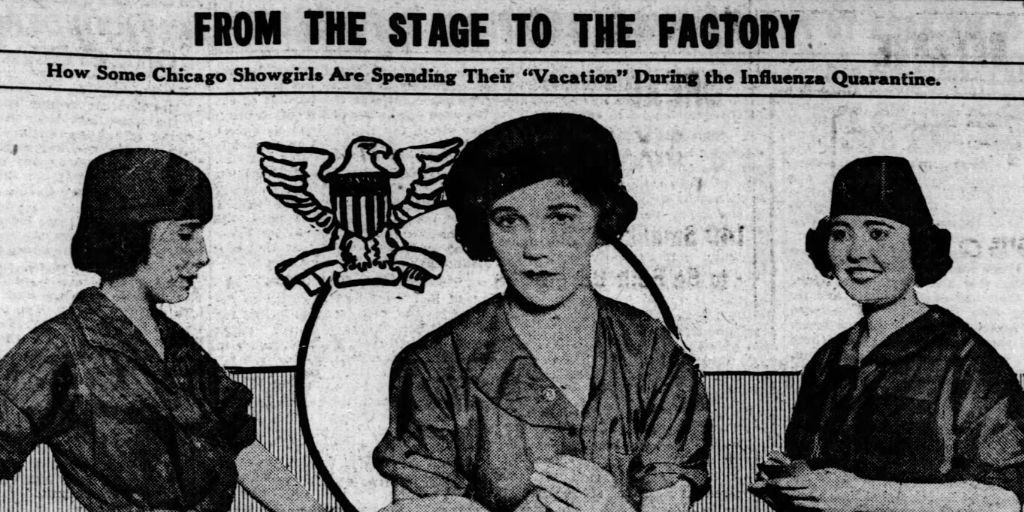

For some who were out of work, picking up a new job meant helping with the country’s World War I efforts.

With theaters and cabarets closed, actresses and dancers worked at munitions plants.

With theaters and cabarets closed, actresses and dancers worked at munitions plants.

After several intense months, the worst of the flu pandemic had passed in Chicago. What’s the takeaway for those of us staying at home?

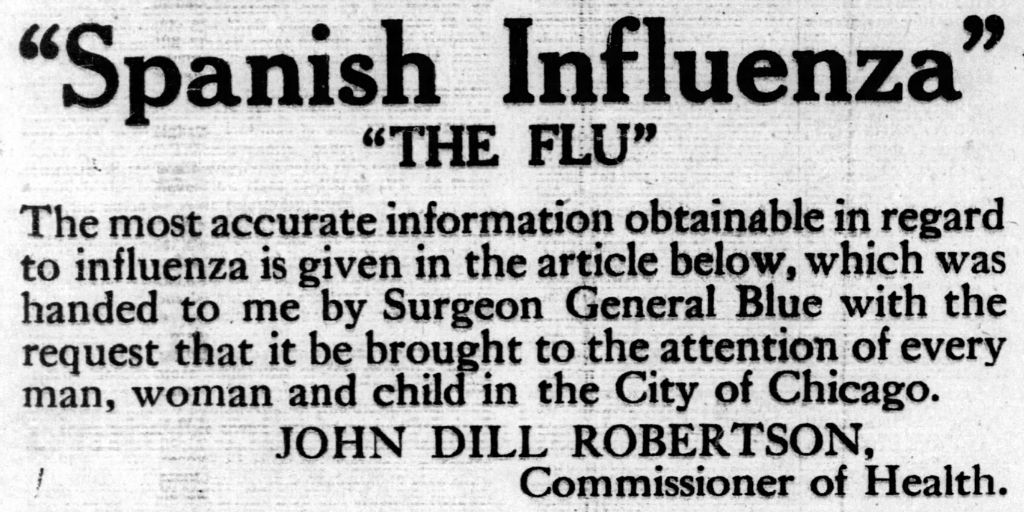

As Dr. John Dill Robertson, Chicago’s health commissioner in 1918, said:

“Cover up each cough and sneeze,

If you don& #39;t you& #39;ll spread disease.”

As Dr. John Dill Robertson, Chicago’s health commissioner in 1918, said:

“Cover up each cough and sneeze,

If you don& #39;t you& #39;ll spread disease.”

Read more about how the 1918 flu pandemic mirrors today’s coronavirus crisis here: https://www.chicagotribune.com/coronavirus/ct-opinion-flashback-1918-flu-pandemic-timeline-htmlstory.html">https://www.chicagotribune.com/coronavir...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter