ॐ पूर्णमदः पूर्णमिदं पूर्णात्पूर्णमुदच्यते ।

पूर्णस्य पूर्णमादाय पूर्णमेवावशिष्यते ॥

If we remove infinity from infinity, what is still prevailing is infinity.

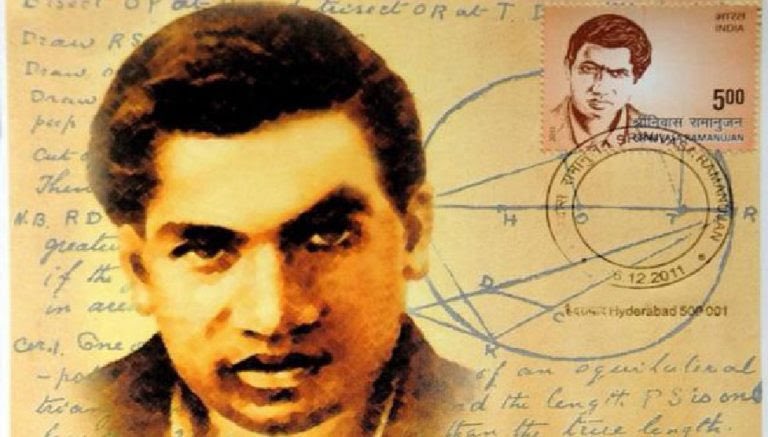

The Man who knew Infinity - Remembering Ramanujan on his 100th Death Anniversary today.

पूर्णस्य पूर्णमादाय पूर्णमेवावशिष्यते ॥

If we remove infinity from infinity, what is still prevailing is infinity.

The Man who knew Infinity - Remembering Ramanujan on his 100th Death Anniversary today.

Though Ramanujan lived only for 32 short years, but he made such an impact on Mathematics that he still continues to be an inspiration for mathematicians across the world.

He was a prodigy and a mathematical genius. He emerged from extreme poverty to become one of the most influential mathematicians. As a boy he refused to learn anything but mathematics,was almost entirely self taught and his pre-Cambridge work is contained in a series of Notebooks

The work he did after returning to India in 1919 is contained in the misleadingly named Lost Notebook. It was lost and later found in the Wren library. While in England Ramanujan became the second Indian Fellow of the Royal Society, he was also the youngest fellow at that time.

Srinivasa Ramanujan had his interest in mathematics unlocked by a book. It wasn’t by a famous mathematician, and it wasn’t full of the most up-to-date work, either. The book was A Synopsis of Elementary Results in Pure and Applied Mathematics by George Shoobridge Carr.

The book consists solely of thousands of theorems, Ramanujan encountered the book in 1903 when he was 15 years old

That book was not an orderly procession of theorems all tied up with tidy proofs encouraged Ramanujan to jump in and make connections on his own. However, since the proofs included were often just one-liners, Ramanujan had a false impression of the rigor required in mathematics.

Despite being a prodigy in mathematics, Ramanujan did not have an auspicious start. He obtained a scholarship to college in 1904, but he quickly lost it by failing in nonmathematical subjects. Another try at college in Madras also ended poorly when he failed his First Arts exam.

It was around this time that he began his famous notebooks. He drifted through poverty until in 1910 when he got an interview with R. Ramachandra Rao, the secretary of the Indian Mathematical Society. Rao was at first doubtful about Ramanujan but eventually recognized his ability

Ramanujan rose in prominence among Indian mathematicians, but his colleagues felt that he needed to go to the West to come into contact with the forefront of mathematical research. Ramanujan started writing letters of introduction to professors at the University of Cambridge.

His letters went unanswered, but his third to G.H. Hardy—hit its target. He included nine pages of mathematics. Some of these Hardy already knew; others were completely astonishing to him,that culminated in Ramanujan coming to study under Hardy in 1914 who became his Mentor.

Once Hardy took a cab to visit Ramanujan.he told Ramanujan that the cab number, 1729, was “rather a dull one.” Ramanujan said, “No, it is very interesting number. Its smallest number expressible as a sum of two cubes in two different ways. That is, 1729 = 1^3 + 12^3 = 9^3 + 10^3.

This is now called the Hardy-Ramanujan number, and The next number in the sequence, the smallest number that can be expressed as the sum of two cubes in three different ways, is 87,539,319.

Ramanujan& #39;s work today have use in particle physics or in the calculation of π up to very large number of decimal places but Ramanujan did mathematics for its own sake, for the thrill that he got in seeing and discovering unusual relationships between various mathematical objects

He provided solutions to problems that were then considered unsolvable. some of his work was so ahead of his time that we are still understanding its relevance. Ramanujan found a formula for computing π (pi) that currently is basis for the fastest algorithms used to calculate π.

Ramanujan frequently said, "An equation for me has no meaning, unless it represents a thought of God."Like ancient Indian mathematicians, Ramanujan only noted the results and summaries of his works; no proof was worked out for the formulae he came up with.

He credited his work to the divine providence of Mahalakshmi of Namakkal, a family goddess whom he looked to for inspiration.

Plenty of mathematicians, Hardy knew, could follow a step-by-step discourses unflaggingly—yet counted for nothing beside Ramanujan.

Years later, he would contrive an informal scale of natural mathematical ability on which he assigned himself a 25 and Littlewood a 30. To David Hilbert, the most eminent mathematician of the day, he assigned an 80. To Ramanujan he gave 100.

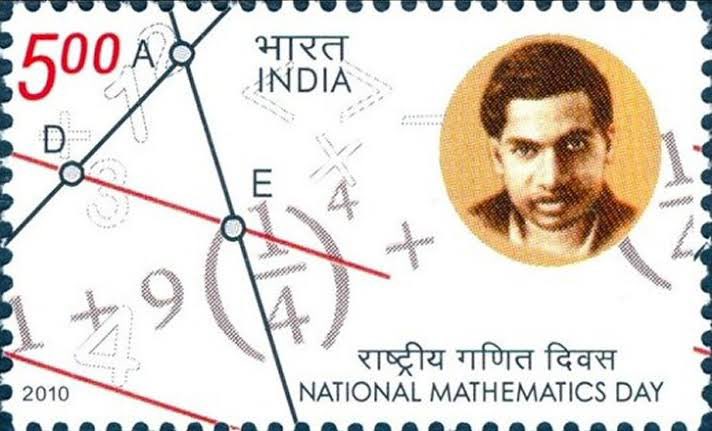

He was a Pure Mathematician unlike Newton. Had Ramanujan been born 10-20 years later, his impact on world of Mathematics,Physics and Computing would have been different. In honor of his accomplishments, his birthday 22nd December is celebrated at National Mathematics Day.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter