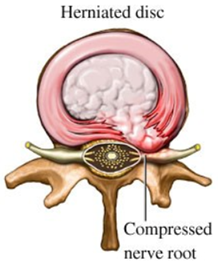

The classical explanation of annulus fibrosus failure is NOT the anatomy of failure in lumbar disc herniation (LDH).

@PeteOSullivanPT @PeterBrukner @kieranosull @MaryOKeeffe007 @function2fitnes @AdamMeakins

@PeteOSullivanPT @PeterBrukner @kieranosull @MaryOKeeffe007 @function2fitnes @AdamMeakins

Excuse my (hopefully) catching and maybe slight provocative heading. I am a physiotherapy student who wants to embark on this exploratory journey with the hopeful help of more experienced minds.

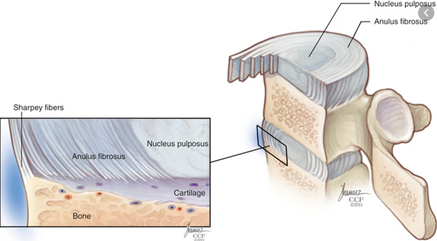

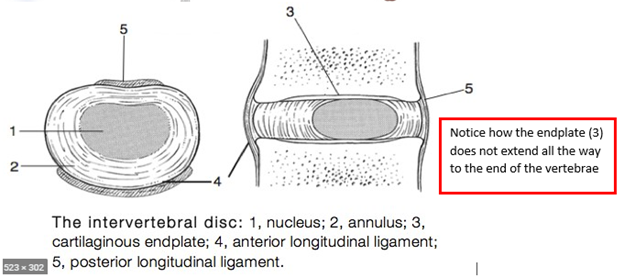

In this thread, I want to propose that the anatomy of failure is the end-plate (EP), rather than the annulus fibrosus (AF). Hopefully, this might add some clinical value and a proposed explanation as to why some patients do worse in the long-term following a disc herniation.

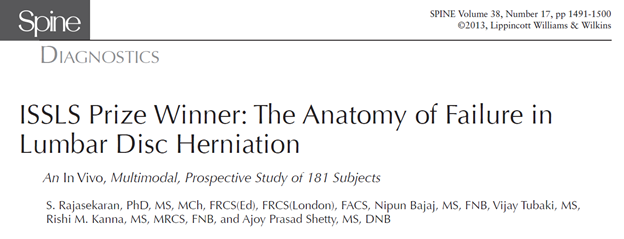

In 2013, Rajasekaran et al. published an in vivo paper where they studied 181 patients who were scheduled to undergo microdiscectomy at a single level. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23680832 ">https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23...

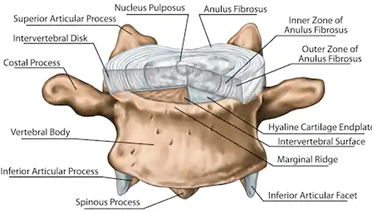

A variety of imaging instruments was used to evaluate the condition of the endplate and the annulus fibrosus, as well as histopathological analysis.

The surgeon inspected the disc in question for AF-tear. When no rupture was identified the surgeon carefully removed the herniated material, visualized it under a microscope and palpated for end-plate cartilage and bony fragments.

Histological evidence of end-plate material in the herniated disc was observed in 70 %.

The anatomy of failure is made elusive by the fact that the authors were only able to identify 12 % of the end-plate failures with plain radiographic identification. The identification increased to 58 % when CT was used.

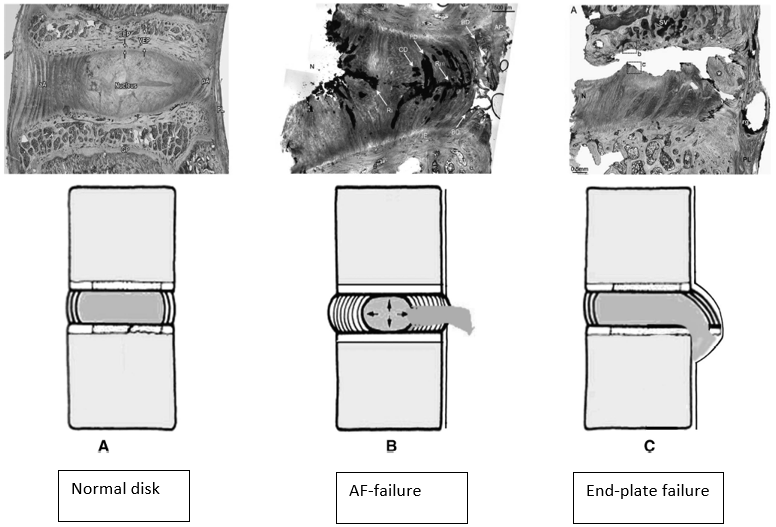

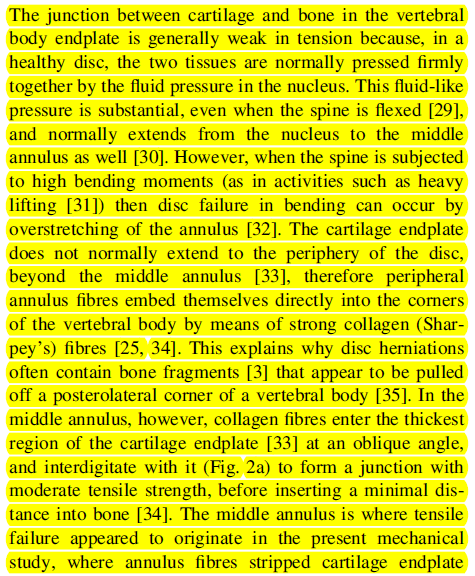

The results from the paper conclude that LDH was more commonly associated with end-plate failure (EPF).

65 % of LDH was due to EPF, whereas 35 % had intact end-plate, suggesting an AF disruption.

65 % of LDH was due to EPF, whereas 35 % had intact end-plate, suggesting an AF disruption.

A similar article was published in 2014 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24947181

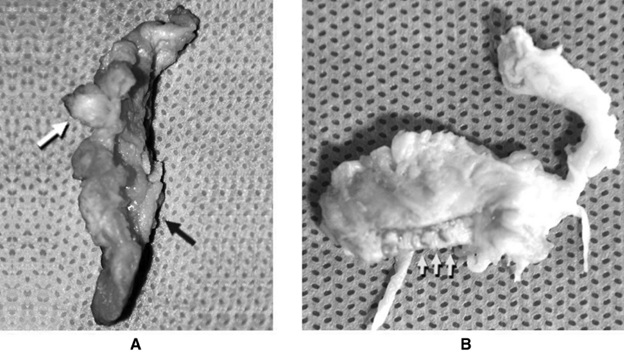

The">https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24... herniation was removed surgically from 21 patients.

Cartilage fragments in 10/21 specimens, on average 5 mm in length, comprised 25 % of the herniation area, and 2 had some bone attached.

The">https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24... herniation was removed surgically from 21 patients.

Cartilage fragments in 10/21 specimens, on average 5 mm in length, comprised 25 % of the herniation area, and 2 had some bone attached.

Moreover, cartilage was more common in herniations from patients with sciatica (7/10). These patients tended to have a longer history of symptoms, but patient groups were too small for reliable analysis.

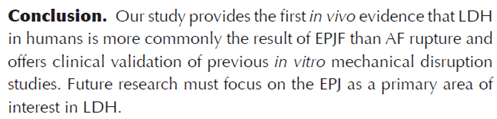

The paper also proposes an explanation as to why the EP fails. Here, I will let the paper speak for itself. See picture with highlighted text.

In general, the natural history of LDH is favorable. The paper from 2014 argues that: “Due to the relatively stable physical properties of hyaline cartilage, together with its ability to synthesize pro-inflammatory mediators such as TNF α, could explain why...

...clinical symptoms are more likely to persist in those patients with a cartilaginous herniation”.

Additionally, hyaline cartilage takes longer to reabsorb due to its tight collagen network and lack of proteoglycan loss when exposed to the exterior environment. This is in contrast to nucleus pulposus and annulus fibrosus which are more easily reabsorbed.

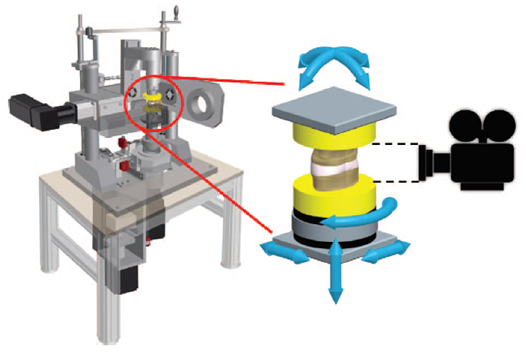

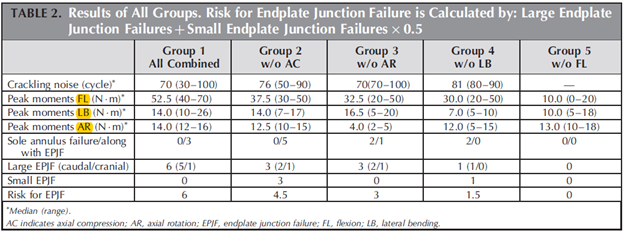

Roscher et al. placed 30 lumbar spine segments from sheep in a 6-degree-of-freedom disc loading simulator. The purpose of the study was to investigate how different loading combinations influence the mechanism and extent of intervertebral disc failure. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27187053 ">https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27...

A total of 21 specimens (70 %) failed of which the majority was EPF (76 %), whereas the rest were annulus failure. Moreover, the combination of flexion, lateral bending, rotation, and compression has the highest risk for caudal EPF.

Flexion without lateral bending and vice versa have the lowest failure rate, strengthening the proposition that lifting with a flexed back is safe.

I came across this literature while spending 2 months in an orthopedic hospital and found it very interesting. I will be looking forward to your response!

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter