Today’s SCOTUS decision in Ramos v. Louisiana is complicated. Different combinations of Justices agreed on different issues. The most important outcome is that it is now a constitutional rule that a person cannot be sent to prison unless 12 jurors unanimously agree about guilt.

Justice Gorsuch wrote the majority opinion. Justices Ginsburg, Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kavanaugh joined different sections of the majority opinion. Justice Thomas wrote his own separate opinion where he agreed with the outcome but used different legal reasoning.

Justice Alito wrote the dissenting opinion. Chief Justice Roberts joined the entire dissent. Justice Kagan joined all but one section of the dissent.

So, in terms of the outcome, the vote was 6-3. Justices Gorsuch, Ginsburg, Breyer, Sotomayor, Kavanaugh, and Thomas voted to get rid of non-unanimous jury verdicts. Justice Alito, Chief Justice Roberts, and Justice Kagan essentially voted to keep non-unanimous jury verdicts.

Evangelisto Ramos, the person who brought this legal challenge, was convicted by a jury vote of 10-2. Two of the jurors thought that he was not guilty. Under Louisiana (and Oregon) law at the time, that was enough to send Mr. Ramos to prison for the rest of his life.

Justice Gorsuch explained the racist origins of these non-unanimous jury laws. Louisiana’s non-unanimous jury law was enacted at a constitutional convention in 1898. It says right in the record of the convention that the purpose was to “establish the supremacy of the white race.”

Louisiana state courts have already ruled that the purpose behind the non-unanimous jury law was “to ensure that African American juror service would be meaningless.” The same was true in Oregon, where non-unanimous jury laws were enacted during the rise of the Ku Klux Klan.

Non-unanimous juries were a deviation from the norm. At the time the U.S. Constitution was written, unanimous juries had been required under the law for over 400 years. Everyone knew that a jury had to vote unanimously before a person could be criminally punished.

Things took a strange turn in 1972 when the Supreme Court considered two related cases—Apodaca v. Oregon and Johnson v. Louisiana. Four justices said unanimous juries were required. Four other justices said unanimity wasn’t worth it. What about the ninth vote?

The ninth justice decided to split the baby. He said that unanimous juries were required, but that requirement didn’t apply to the states. This idea was based on a legal theory that had already been rejected by a majority of the Court multiple times before (and after) 1972.

The majority in today’s Ramos decision heavily criticized the 1972 Apodaca decision as wrongly decided. Justice Gorsuch wrote that the 1972 Court only spent one paragraph analyzing the legal problem. And the ninth justice who split the baby in 1972 refused to follow the law.

Justice Gorsuch also criticized Justice Alito’s dissent, writing that aspects of Alito’s opinion were “overstatements” that must have been “intended for dramatic effect.”

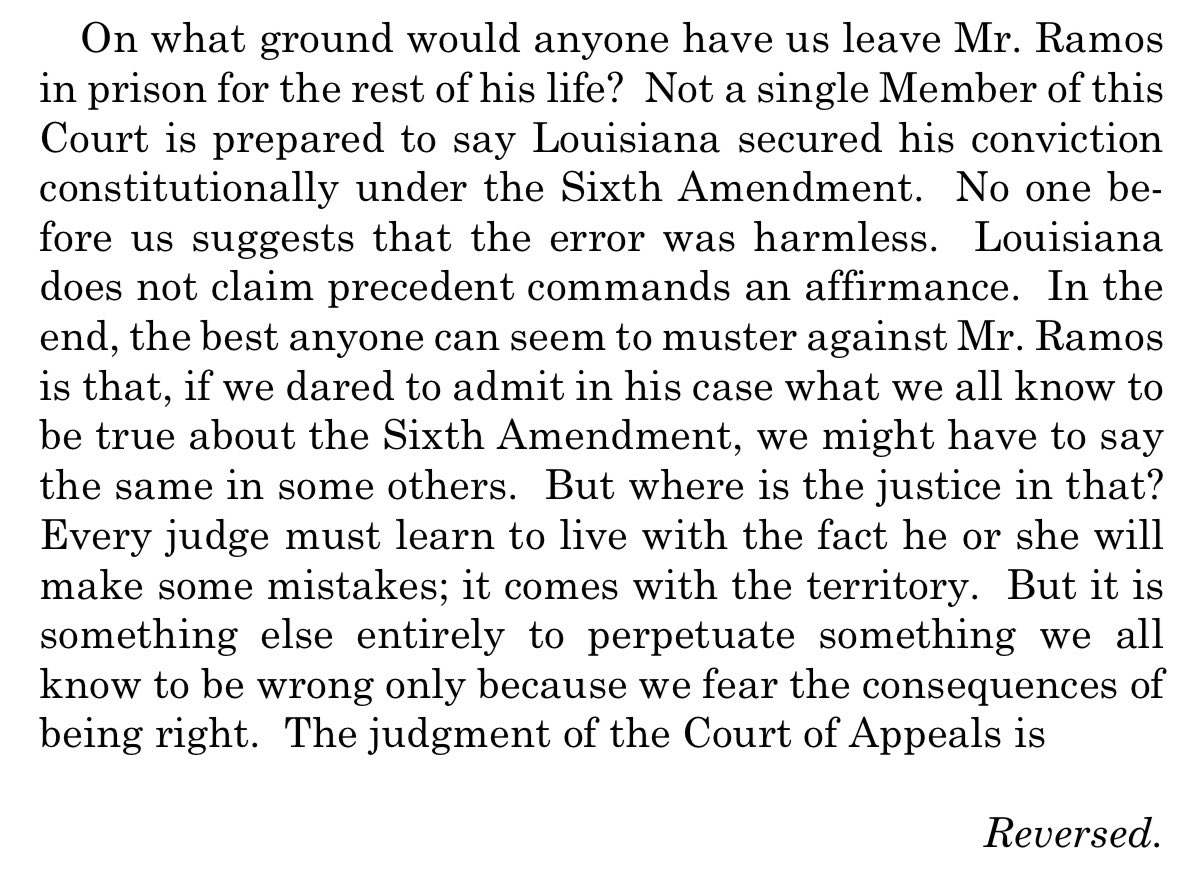

At the end of the majority opinion, Justice Gorsuch summed the case up well. It’s worth reading in full:

Justice Sotomayor filed a concurring opinion. She did two interesting things. First, she took some of the dissenters to task for their willingness to overrule longstanding precedent in some partisan cases but not on this question of fundamental constitutional rights.

Second, Justice Sotomayor pointed out that it was important for the Court to address the racist origins of non-unanimous jury laws precisely because states have never truly grappled with this history of racial bigotry.

Justice Kavanaugh also wrote a concurring opinion about his view of when the Court should overrule precedent. Kavanaugh concluded that the 1972 Apodaca decision allowing non-unanimous jury verdicts was “egregiously wrong” and that it is time to overrule it.

Justice Thomas wrote an opinion concurring with the outcome. Thomas thinks that the decision to get rid of non-unanimous jury verdicts is correct, but he would have used a different clause in the Constitution to get to that result.

Then there’s Justice Alito’s dissent. Alito begins by claiming that no Justice has ever said that Apodaca should be overturned. But that’s not quite accurate. A majority of the Court has said that juries must be unanimous several times after 1972, directly contradicting Apodaca.

Alito wrote that the majority was wrong to acknowledge the racism behind non-unanimous jury laws. He said that the majority acted in line with “the worst current trends” by not engaging in “rational and civil discourse.” How is pointing out racism a bad trend or irrational?

Justice Gorsuch responded to Alito’s criticism: “Our shared respect for ‘rational and civil discourse’ cannot supply an excuse for leaving an uncomfortable past unexamined.”

Justice Alito’s dissent argues that the old rule of non-unanimous juries should be kept because overruling it would mean that states have to retry people who were convicted in violation of the Constitution. Gorsuch responds: “The [dissent’s] worries outstrip the facts.”

Justice Gorsuch characterizes the dissent’s argument well. Basically, Alito’s dissent argues that if the Court does what everyone knows is right in this case, then the Court might have to do the right thing in other cases as well. Think about the moral clarity there.

This reminds me of Justice William Brennan’s incisive observation in McCleskey v. Kemp: the U.S. Supreme Court is often afraid of delivering “too much justice.” Luckily, that fear did not win the day this time.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter