= Jiang Cheng’s siege as gossip frames it =

- quote, don’t reply

- open to corrections and additions!

- this relies on the novel verse, not CQL, where he’s more outright vilified

- get ready for a little history and also poetry

- Sources from Baidu and the MDZS novelization

- quote, don’t reply

- open to corrections and additions!

- this relies on the novel verse, not CQL, where he’s more outright vilified

- get ready for a little history and also poetry

- Sources from Baidu and the MDZS novelization

In the first chapter, we are informed that Jiang Cheng lead the siege that contributed to Wei Wuxian’s d**th, and get a view of local gossips discussing their connection to each other as well as the specific nature of his role in Wei Wuxian& #39;s demise.

EXR had translated his act of besieging the Burial Mounds as “putting an end to his own relative for the greater good”, however, this doesn’t quite encompass the scope of the original phrase used in Chinese.

The original phrase in Chinese being used was “大义灭亲”, which, while “putting an end to his relative for the greater good” does, in a sense, fulfill the bare meaning of this term, it’s an idiom, which is usually attached with a story to help make sense of it.

These stories help contextualize the value and culture quite a lot. This one took place in the Wey State during the Spring-Autumn Period. Duke Zhuang I of Wei had three sons, and he loved his third son and coddled him so much he became a cruel and entitled person with a temper.

Shi Que, an official, had attempted to advise Duke Zhuang to rein in his son, but the Duke never heeded. Shi Que’s own son Shi Hou befriended the third son Zhou Xu. Also at some point, the eldest brother, Duke Huan, succeeded their father.

(Shi Que, Zhou Xu, Shi Hou)

(Shi Que, Zhou Xu, Shi Hou)

In 719, Zhou Xu gathered a group of Wey exiles and assassinated his elder brother, Duke Huan of Wey, in an attempt to seize the throne. Shi Que had enlisted the power of the Duke of Chen to trap and execute the usurper, and then also had executed his son for his role in the coup.

This is the story of “大义灭亲”, originally used to describe a father ordering the execution of his own corrupt son to stop a tyrant from taking power, and refers to the need to overlook someone& #39;s familial ties or friendship to oneself to uphold justice

In a modern context (as helped put into perspective by my roommate, thanks roomie! <3) one might say, imagine if you had a sibling you were really close to and treasured. Imagine if this sibling comes to you one day confessing they m*rd*r*d someone in cold blood.

大义灭亲 means if your sibling had asked you to help them escape or hide from authorities for their crime, you would refuse to do this and turn them in. No matter how close you once were, no matter how much you loved them. Because to do so is to help a m*rd*r*r walk free.

大义灭亲, thus refers to Jiang Cheng having to put aside his childhood sentimentality and his closeness to Wei Wuxian to bring him down /for the sake of justice/. As Sansa Stark says in this poorly cropped and no doubt grainy pic, it& #39;s not what he wants, it& #39;s what honor demands.

And what does honor demand?

That he avenge the wrongful d**ths of his sister and his brother-in-law.

That he answer to the rest of the sects of the bloodshed Wei Wuxian brought upon them, and in a way, take responsibility for this as Wei Wuxian& #39;s former liege and brother.

That he avenge the wrongful d**ths of his sister and his brother-in-law.

That he answer to the rest of the sects of the bloodshed Wei Wuxian brought upon them, and in a way, take responsibility for this as Wei Wuxian& #39;s former liege and brother.

People like to cast blame on Jiang Cheng because he led the siege, but at this point, Wei Wuxian was so far gone he lost control of his powers to the extent of k***ing his brother in law, k*** 3000 people, and lashed out at the man who would stand against the world for him.

In other words, Wei Wuxian was heavily unstable, in possession of a weapon of mass destruction, and had already set precedent by committing an unbelievable bloodbath. There were few realistic options Jiang Cheng could choose for dealing with him at this point beyond the siege.

I also want to note a confirmation (or at least accusation) that he besieged Wei Wuxian not out of hatred, but out of what duty demanded of him with this difference in translation. In particular, I want to examine the phrase "青梅竹马" people use to describe their relationship.

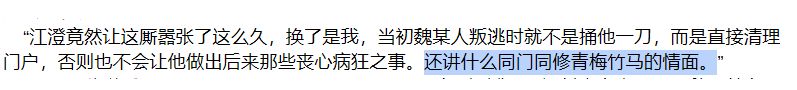

Essentially, this gossip insists that Jiang Cheng was far too lenient with Wei Wuxian even after his defection and if it were him, he wouldn& #39;t have just left it at a st*b but gone the full nine yards. He finishes by asking who even cared about how close they were as children.

The phrase used, 青梅竹马, comes from a Tang poem by Li Bai, 《长干行》, about a husband and wife who were childhood sweethearts, but the passage from which it came describes two young children in the peak of their innocence.

郎骑竹马来,

绕床弄青梅,

同居长干里,

两小无嫌猜。

郎骑竹马来,

绕床弄青梅,

同居长干里,

两小无嫌猜。

Translated, it means

You came around on your bamboo horse

Encircling chairs and benches and dangling in your hand was a branch of green plums.

We both lived in the region of Changgan,

Two youngsters who hadn& #39;t thought much.

From: https://28utscprojects.wordpress.com/2011/01/20/043/ ">https://28utscprojects.wordpress.com/2011/01/2...

You came around on your bamboo horse

Encircling chairs and benches and dangling in your hand was a branch of green plums.

We both lived in the region of Changgan,

Two youngsters who hadn& #39;t thought much.

From: https://28utscprojects.wordpress.com/2011/01/20/043/ ">https://28utscprojects.wordpress.com/2011/01/2...

It paints a picture of an idyllic childhood, one that the gossip acknowledges that Jiang Cheng and Wei Wuxian must have shared-- (a childhood that Jiang Cheng proves through the text he wishes he could go back to) but one which Jiang Cheng should have done away with memories of.

Essentially, through the opening, it& #39;s established that Jiang Cheng besieged Wei Wuxian out of duty, and he does this DESPITE his love for his brother (a sentiment that he& #39;s criticized for), and it sets up his later conflicts between being honorable and protecting his brother.

= End thread =

Feel free to comment any questions, corrections, etc. under this tweet!!

Feel free to comment any questions, corrections, etc. under this tweet!!

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter