Do you want to know a secret?

All history is subjective.

There, I said it. But we will not just leave it at that. It& #39;s time for #MethodologyMonday: the Objectivity Paradox. History as a particle and as a wave. A thread https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🧵" title="Thread" aria-label="Emoji: Thread"> 1/

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🧵" title="Thread" aria-label="Emoji: Thread"> 1/

All history is subjective.

There, I said it. But we will not just leave it at that. It& #39;s time for #MethodologyMonday: the Objectivity Paradox. History as a particle and as a wave. A thread

We start, as so many misfortunes, in the 19th century. In 1885 a German historian Leopold von Ranke wrote one of the most famous sentences in modern historiography:

bloß zeigen, wie es eigentlich gewesen

Bear with me, because everybody misunderstood him. 2/

bloß zeigen, wie es eigentlich gewesen

Bear with me, because everybody misunderstood him. 2/

In older English versions this sentence was translated as "merely to show how it really was". So understood it reeks of positivistic approach. The historian is there just to discover objective facts. If they do their job correctly they will uncover the "truth" about the past. 3/

What Ranke *actually* meant was "merely to show how it *essentially* was" - to spin a narrative web that will convey to its readers the essence of the past. Ranke understood very well that history is a subjective discipline and he was right. But wait! If this is the case... 4/

...how can historians pontificate about history at all? If all is subjective then surely historians have no right to say things like "nope, it wasn& #39;t like that" or to even claim that they can ascertain anything about the past. It turns out they can and there is a method to it. 5/

Throughout history of historiography many methods were developed in order to sort this paradox: if all historiography is subjective how can we know anything about the past at all? And how do we remain truthful if we know we are subjective? 6/

Historians are often uncomfortable about the objectivity paradox but do not mistake this healthy sense of unease for confusion. If you allow I& #39;ll again use a physics analogy to show just two strategies to deal with it. History as a collection of waves and as made of particles. 7/

Usual disclaimer: we will make certain comparisons and metaphors here. They might be risky but it& #39;s all for a good cause! 8/

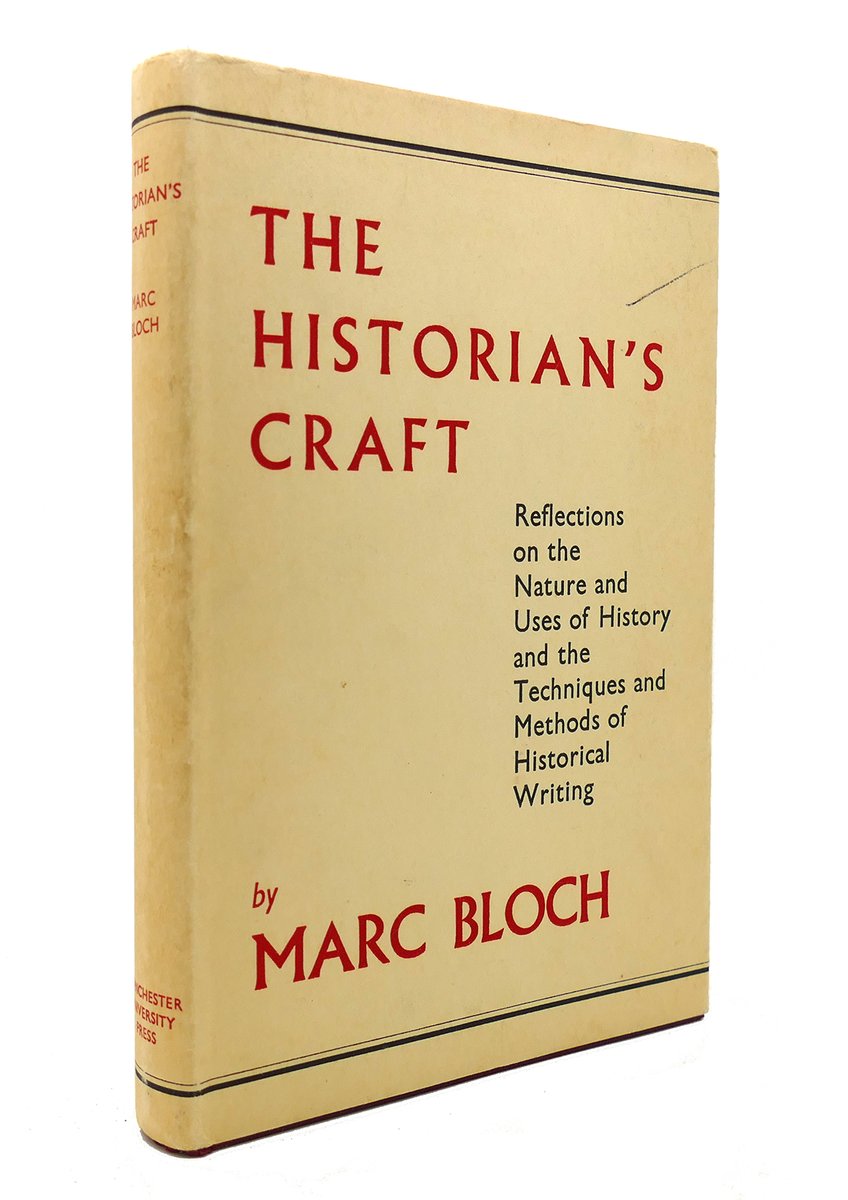

To grasp the first idea we look at the darkest of times. Between 1941 and 1943 Marc Bloch, a French-Jewish historian, hiding from the Gestapo, wrote The Historian’s Craft. It’s the best explanation of being a historian and lays down a model to solve the objectivity paradox. 9/

For Bloch it is important not to be judgmental but instead descriptive. This sounds like he advocated objective history, but the model is more complicated. The causes of history are to be looked for and not assumed: the solution is in seeing historian’s craft as a process. 10/

In this model history is a wave, an oscillating line, which allows the regressive method: a technique to draw what we cannot deduce directly from the sources of the time from other times. Because both the method and the subject were a line, history is a process of discovery 11/

Same as in the whole of Annales school the particular small “phrases” of history, seen through a methodological microscope, for Bloch bring very little. Only if we add them up to a wave they can be put into a narrative. But this adding up is not arbitrary! 11/

It has to be done in accordance to what we know from the sources and the methodological rules. Historians for Bloch are not mere detectives, they are not to discover “objective” little facts and present them in little display cases. They have a responsibility to add them up. 12/

So in "history as a wave" if the phrases do not add up according to the rules of method and the sources the resulting narrative is in discord, it presents a distorted image of the past and has to be discarded. If the model cannot be tested against the evidence it& #39;s wrong. 13/

As a little aside, please do read this amazing thread on Bloch by @medievalguy:

https://twitter.com/medievalguy/status/1140603613565325313?s=20

And">https://twitter.com/medievalg... now, on to the second part today. 14/

https://twitter.com/medievalguy/status/1140603613565325313?s=20

And">https://twitter.com/medievalg... now, on to the second part today. 14/

There is another model to deal with this dilemma. History as a set of particles. In 1961 British historian E. H. Carr published What is History? (he did not think small this Carr guy…) There he introduced the idea of “historical facts” and “facts of the past”. 15/

In this model facts of the past might well remain objective but they are directly inaccessible. The only way to get to them is through historical facts – products of historians themselves, inadvertently subjective and building together narratives that we call “history” 16/

This method, based on de Saussure’s linguistic structuralism, was better expressed in Polish historiography, where Topolski introduced “historiographical facts” and “historical facts”. Thus the multitude of interpretations is restrained by what can be found in the sources. 17/

You can already sense a common theme: yes, the historiography is always subjective. Yes, we look at the past through a glass darkly (or, replacing St Paul with Philip K. Dick, through a scanner darkly if we take into account digital methods) and our projections are subjective 18/

But what remains non-arbitrary is the method itself. Because ultimately yes, everything could have happened in the past, but only that what is accessible through the sources and the method can be put into historical narrative. The method serves as a restrictive constant. 19/

It might, at first, sound counterintuitive but this is the crux of the solution to the objectivity paradox. This allowed Bloch to vehemently oppose Nazi theories about the past: they were not only morally wrong but also because they were contrary to method and the source base 20/

This is why historians *can* say that “nope, it wasn’t like that” because through applying rigorous method they can check which models stand to the scrutiny of the sources and our accumulated knowledge about the past. History is not just a collection of random facts. 21/

Transparency about those methods and sources is key: historians must be able to show which glass or which scanner they use to look. Notice also that pretending to be objective can be more deceptive than admitting subjectivity. History is not a sleigh of hand. 22/

History is an evolving discipline. We& #39;ve developed other models to deal with the objectivity paradox (we& #39;ll touch upon them in the postmodern historiography thread). We know now that history is both a particle and a wave. New methods are being developed, we critique the old. 23/

We know that the sources we have are also subjective but we have rigorous source critique methods to evaluate them. This is why we can put them into models that we develop and test and why we can fight fake news about the past while remaining engaged in our interpretations. 24/

There is a final twist. As all past is political and all historical narratives subjective – products of their times – they remain relevant here and now. Through one of its greatest challenges history remains alive.

As Benedetto Croce said: all history is contemporary history 25/

As Benedetto Croce said: all history is contemporary history 25/

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter