I was thinking about that natural nuclear reactor in Gabon and thinking about iron asteroids and things and was wondering if it would be possible for there to somehow be a natural fusion reactor, somewhere out in the universe...

stars. I just invented stars. idiot.

stars. I just invented stars. idiot.

and yes, the NATURAL NUCLEAR REACTOR is real.

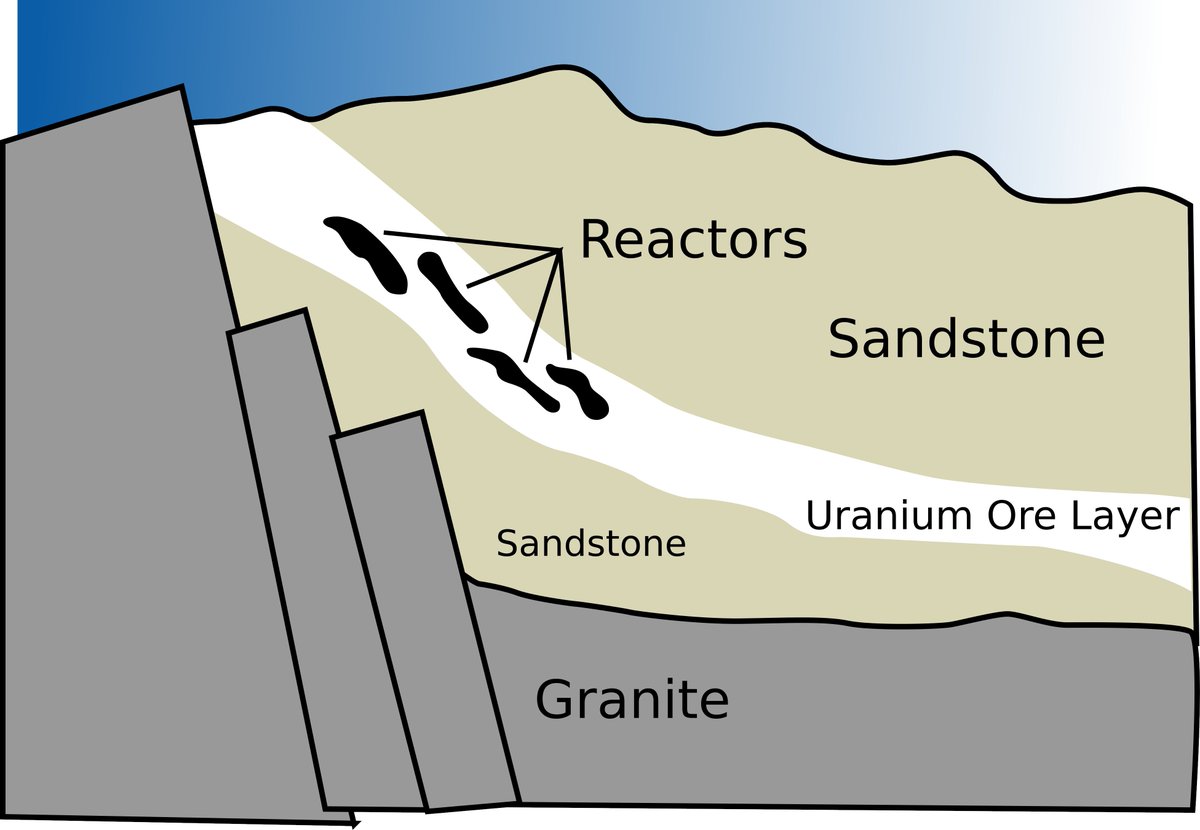

There are 16 known sites under Oklo, Gabon where natural nuclear reactors ran for hundreds of thousands of years, about 1.7 billion years ago.

There are 16 known sites under Oklo, Gabon where natural nuclear reactors ran for hundreds of thousands of years, about 1.7 billion years ago.

The way it worked is there is a mineral deposit that has a higher proportion of uranium than most other deposits, but that alone isn& #39;t enough to work as a reactor

so the super quick simplified model of how nuclear reactors work: You have fissile material like U-235, it splits, producing neutrons. These neutrons hit other U-235, triggering them to also split, creating more neutrons.

So it& #39;s a self-powering chain reaction.

So it& #39;s a self-powering chain reaction.

But the problem is that the neutrons coming out of U-235 when it splits have a lot of energy, and some of that energy is kinetic: they& #39;re moving fast (really fast: like 10% of the speed of light). And when they& #39;re moving fast they& #39;re not likely to actually hit another U-235

so to get a self-sustaining reaction, you want to slow them down.

So you need a neutron moderator. This is a medium you put the u-235 in, and it slows down these neutrons so they& #39;ll have a better chance to interact and cause more fission, and it becomes self-sustaining

So you need a neutron moderator. This is a medium you put the u-235 in, and it slows down these neutrons so they& #39;ll have a better chance to interact and cause more fission, and it becomes self-sustaining

Artificial nuclear reactors (you know, the normal kind) mostly use water. Often plain normal water (it& #39;s cheap and easy to get and you don& #39;t have to worry about pollution!) but heavy water is also used.

Graphite is another popular choice (and helped cause Chernobyl!)

Graphite is another popular choice (and helped cause Chernobyl!)

So while there& #39;s plenty of natural uranium ore around the world, it doesn& #39;t normally cause reactions, because whenever some of the uranium decays and shoots out neutrons, those neutrons are fast neutrons, and they& #39;re unlikely to trigger any further fission.

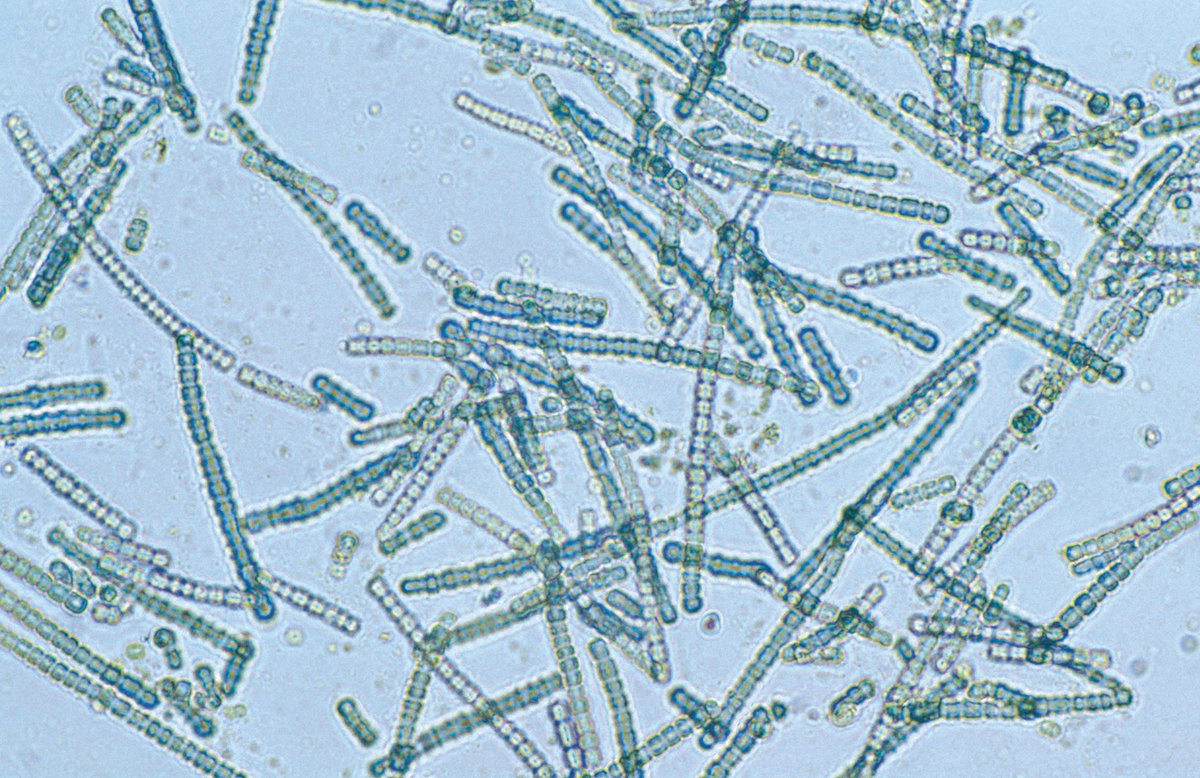

but in the Gabon deposits, the ore was particularly rich, and a recent development had caused the world to be full of oxygen: the Great Oxidation Event.

2.4-2.1 billion years ago, the atmosphere of earth went from barely any oxygen to about the current levels.

2.4-2.1 billion years ago, the atmosphere of earth went from barely any oxygen to about the current levels.

so now that there was tons of oxygen, uranium is water soluble... and that& #39;s what happened. Groundwater seeped into the uranium deposits and started slowing down the fast neutrons flying about

and they slowed down enough to trigger a self-powering fission chain reaction!

... for about 30 minutes.

Then it got warm enough to boil off all the water

... for about 30 minutes.

Then it got warm enough to boil off all the water

As soon as the water was steam, it was no longer as good at slowing down the neutrons, the amount of fission happening went down, and the chain reaction starved and stopped.

... for about 2 and a half hours.

... for about 2 and a half hours.

then it had cooled down enough that the steam had recondensed into water, it& #39;d flowed back into the uranium-rich areas, and the reaction started back up again.

So this cycle, lasting about 3 hours repeated over and over, for hundreds of thousands of years.

So it& #39;s natural reactors that lasted longer than THE ENTIRE HUMAN RACE

So it& #39;s natural reactors that lasted longer than THE ENTIRE HUMAN RACE

eventually these ore deposits were depleted enough that the reaction could no longer take place, and it stopped.

It& #39;s estimated about five tons of U-235 was used up by these natural reactors.

It& #39;s estimated about five tons of U-235 was used up by these natural reactors.

Fun fact: It& #39;s impossible for this to happen now!

It could only have happened 1.7 billion years ago.

It could only have happened 1.7 billion years ago.

Because uranium primarily comes in two isotopes: U-235 and U-238.

U-238 is not fissile, U-235 is.

But U-235 and U-238 are found in the same ore deposits, which is a pain if you want to use them for fission.

U-238 is not fissile, U-235 is.

But U-235 and U-238 are found in the same ore deposits, which is a pain if you want to use them for fission.

so for a bomb or a reactor, you have to enrich the uranium, which just means splitting out the U-235 and the U-238 so that you have a larger proportion of the useful U-235.

So today if you were to go dig up a uranium deposit, you& #39;d find that about 0.7% of it is U-235.

But if you did that 1.7 billion years ago, you& #39;d find that 3.1% would be U-235, which is more like the proportions you& #39;d find in a nuclear reactor today.

But if you did that 1.7 billion years ago, you& #39;d find that 3.1% would be U-235, which is more like the proportions you& #39;d find in a nuclear reactor today.

And the reason for that is simple:

U-235 has a half life of 0.7 million years,

U-238 has a half life of 4.7 billion years

U-235 has a half life of 0.7 million years,

U-238 has a half life of 4.7 billion years

so all the uranium (and all the other unstable elements for that matter) in the earth is slowly decaying, but at different rates because of different half-lifes.

Today, it& #39;s impossible to have a reactor with natural uranium ratios and water.

Today, it& #39;s impossible to have a reactor with natural uranium ratios and water.

you need either a better moderator (heavy water or graphite) or refined uranium, or both.

but 1.7 billion years ago, there was still relatively a lot of U-235 left, and thanks to some Cyanobacteria poisoning the atmosphere with all this "oxygen" crap, suddenly uranium was water soluble, and WHOOPS NATURAL REACTORS!

So, how this was discovered is also interesting:

Uranium had been mined in Gabon, and shipped to a uranium enrichment facility in Pierrelatte, France (for use in nuclear power)

And one of the things you do with uranium is you have to test the U-235/U-238 ratios

Uranium had been mined in Gabon, and shipped to a uranium enrichment facility in Pierrelatte, France (for use in nuclear power)

And one of the things you do with uranium is you have to test the U-235/U-238 ratios

and the reason is for nuclear non-proliferation:

If you& #39;re shipping X tons of raw uranium ore out of your mine to some other country who is going to refine it, are they really going to notice if you sneakily extract some of the U-235? it& #39;s only 0.7% of it!

If you& #39;re shipping X tons of raw uranium ore out of your mine to some other country who is going to refine it, are they really going to notice if you sneakily extract some of the U-235? it& #39;s only 0.7% of it!

and now you& #39;ve got some enriched uranium and you can start building a bomb.

So they use statistics to detect if this has happened: they measure the incoming ore ratios

So they use statistics to detect if this has happened: they measure the incoming ore ratios

because if the ore you& #39;re getting has had some of the U-235 taken out, it won& #39;t be 0.7% anymore, it& #39;ll be a little less, and you& #39;ll know they need to send in the investigators to see what dictator is trying to build a nuke

so the ore coming into the enrichment facility in Pierrelatte used mass spectometry to analyze the isotopic signature of the ore coming in. It should be be somewhere around the natural 0.7% range... but the samples from Oklo Mine in Gabon were 0.6%

And the other isotopes in the samples were also out of their natural proportions: There was less of the Neodymium-142 isotope (which is a common natural isotope), and more of the Neodymium-143 isotope (which is natural, but also created in nuclear reactions)

This was discovered in May of 1972, and the Commissariat à l& #39;énergie atomique (Atomic Energy Commission) began an investigation.

and in September of that year, they released their findings, that there had been a natural reactor under Gabon, and it& #39;d used up some of the U-235.

There& #39;s two other neat scientific ideas that were influenced by this discovery.

First, the fine structure constant, and secondly, the origin of the moon.

First, the fine structure constant, and secondly, the origin of the moon.

The fine-structure constant is a fundamental physical constant that characterizes the strength of the electromagnetic interaction between charged particles.

It& #39;s called alpha, and it& #39;s about 0.0072973525693.

It& #39;s called alpha, and it& #39;s about 0.0072973525693.

So while it can be measured by seeing how particles interact (and through some fun quantum effects), we don& #39;t really know why exactly it& #39;s that number. It just kinda is, because that& #39;s the way the universe works.

and you can also use the anthropic principle on it:

if this was a universe where it was a little bigger, stars wouldn& #39;t make carbon, and there& #39;d be no carbon-based life like us around to wonder about why it& #39;s the number it is.

if this was a universe where it was a little bigger, stars wouldn& #39;t make carbon, and there& #39;d be no carbon-based life like us around to wonder about why it& #39;s the number it is.

and if it was bigger than 0.1, there& #39;d be no stars (since fusion wouldn& #39;t work), and the universe would be a cold dark pile of hydrogen and a few other miscellaneous elements.

But the obvious question when you& #39;re presented with a measurable constant: IS IT ACTUALLY CONSTANT?

because we know that it& #39;s 0.0072973525693 TODAY, was it always that value? maybe this isn& #39;t a constant, maybe it& #39;s something that varies across the universe or over time?

because we know that it& #39;s 0.0072973525693 TODAY, was it always that value? maybe this isn& #39;t a constant, maybe it& #39;s something that varies across the universe or over time?

and we can& #39;t easily fly to the other end of the universe and run the experiments again, so we have to estimate, from telescopes.

And the general consensus for now (there are some dissenters) is that no change happens across either space OR time

And the general consensus for now (there are some dissenters) is that no change happens across either space OR time

except... what about both?

because when you& #39;re looking at something 50 million lightyears away you& #39;re also looking 50 million years back in time. And maybe it& #39;s changing over both space and time, so it only looks like it& #39;s not changing?

because when you& #39;re looking at something 50 million lightyears away you& #39;re also looking 50 million years back in time. And maybe it& #39;s changing over both space and time, so it only looks like it& #39;s not changing?

and it& #39;s not like we can aim a telescope at a mirror 40 million lightyears away and see what earth was like 80 million years ago (HI DINOSAURS)

EXCEPT! we know how the fine-structure constant affects nuclear reactions... and we have a nice example of a natural nuclear reactor that had run 1.7 billion years ago.

So we can look at the ratios of the other isotopes involved and measure what value alpha was!

So we can look at the ratios of the other isotopes involved and measure what value alpha was!

so that& #39;s been done, and the big groundbreaking result was... alpha was exactly the same, as far as we can measure.

Hey, a null result is still a result. Sometimes science is just proving that a theory is wrong.

Hey, a null result is still a result. Sometimes science is just proving that a theory is wrong.

but it& #39;s good to know.

if the fine structure constant had been changing over time, it means the early universe would have worked much differently than the universe works now, and that& #39;d be really important for figuring out the general "how did we get here?" sorts of questions

if the fine structure constant had been changing over time, it means the early universe would have worked much differently than the universe works now, and that& #39;d be really important for figuring out the general "how did we get here?" sorts of questions

as well as the "where will we go from here?" questions.

if it changed in the past, it& #39;ll probably change in the future, and that& #39;s probably not a good sign for continued life in this universe.

FORTUNATELY we seem to be in a universe with a nice, stable, alpha.

if it changed in the past, it& #39;ll probably change in the future, and that& #39;s probably not a good sign for continued life in this universe.

FORTUNATELY we seem to be in a universe with a nice, stable, alpha.

so the even weirder theory involving the gabon reactors:

So, remember how I said it was only possible 1.7 billion years ago because of the uranium ratios being higher?

Well, if you go back further and further in time, they were even higher.

So, remember how I said it was only possible 1.7 billion years ago because of the uranium ratios being higher?

Well, if you go back further and further in time, they were even higher.

eventually you get to a point where they& #39;re so high they don& #39;t need any neutron moderator, the uranium alone would start a reaction, potentially a very big, very fast one.

less like a "reactor" and more like "a bomb".

less like a "reactor" and more like "a bomb".

and that ties back to one of the Big Questions That Has Perplexed Man Since Before Time Immemorial:

Why is there a moon?

Why is there a moon?

Because the moon is weird.

Like, it& #39;s big! it& #39;s too big. It& #39;s almost a twin-planet to the earth.

And the more we& #39;ve learned about the moon, the weirder it& #39;s gotten.

Like, it& #39;s big! it& #39;s too big. It& #39;s almost a twin-planet to the earth.

And the more we& #39;ve learned about the moon, the weirder it& #39;s gotten.

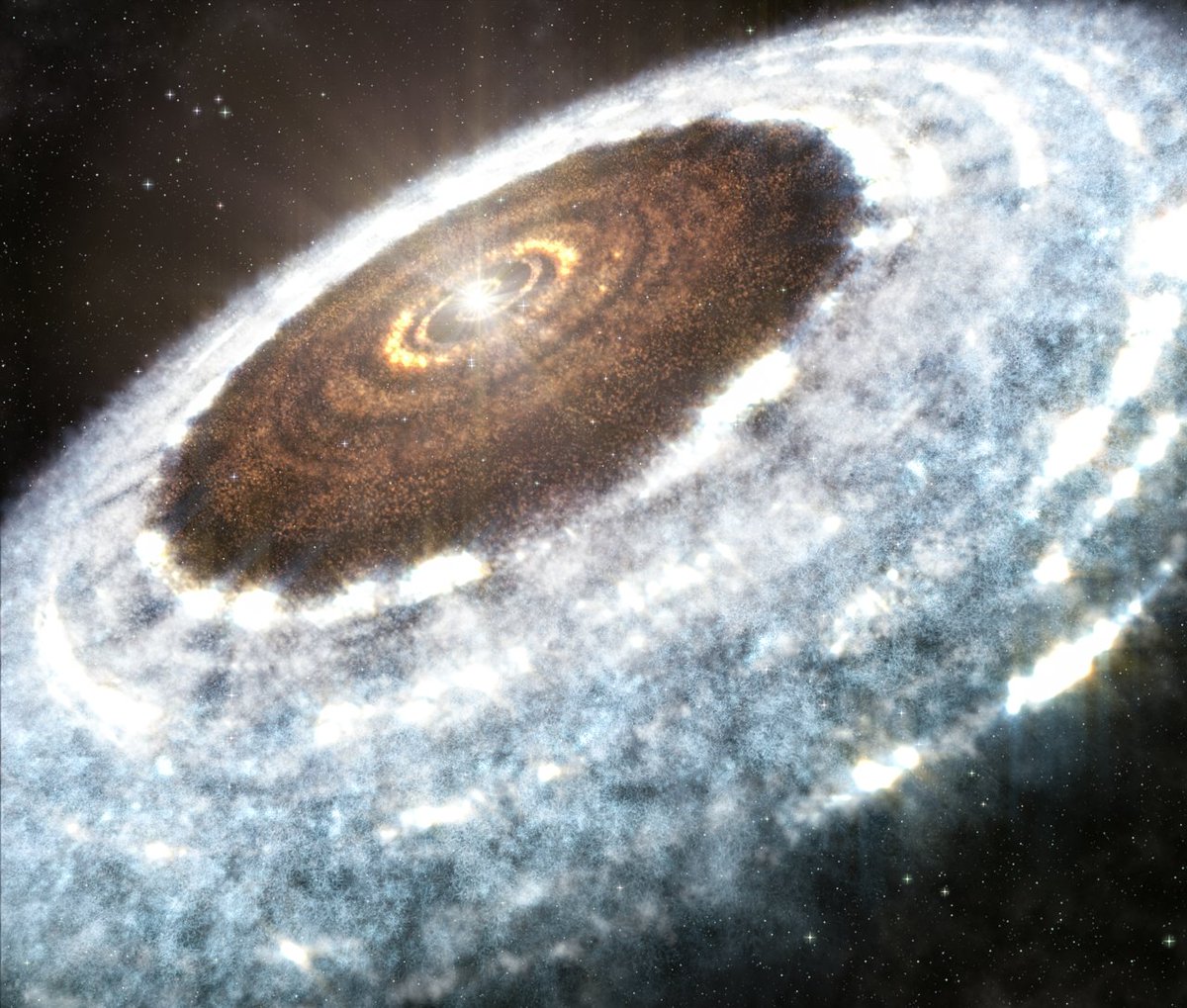

basically, when planets were forming, the protoplanetary disc condensed into a bunch of planets, and smaller chunks that didn& #39;t end up in planets ended up as moons and asteroids.

This is a complex fluid interaction, with slowly-forming proto-planets affecting each other, causing things like how we have an asteroid belt instead of a 5th rocky planet past Mars.

but when you do simulations of how this works, you don& #39;t end up with The Moon.

If there was that much material around the earth& #39;s part of the protoplanetary disc, it& #39;d either end up in the earth, or kept apart, and we& #39;d have several small moons, or many other outcomes

If there was that much material around the earth& #39;s part of the protoplanetary disc, it& #39;d either end up in the earth, or kept apart, and we& #39;d have several small moons, or many other outcomes

but instead, we have a big moon. Weird. Great.

So one earlier theory on "why the fuck is there a moon" was: MAYBE IT& #39;S NOT A MOON?

So one earlier theory on "why the fuck is there a moon" was: MAYBE IT& #39;S NOT A MOON?

I don& #39;t mean it& #39;s a spaceship or anything. Although there& #39;s plenty of sci-fi where that& #39;s the case... I mean that it didn& #39;t start as a moon.

Maybe it was some minor planet off in the asteroid belt or something and it got too close to Jupiter and Jupiter tossed it at us.

Maybe it was some minor planet off in the asteroid belt or something and it got too close to Jupiter and Jupiter tossed it at us.

very early on the Earth may have had a huge "atmosphere" of dust and gas that hadn& #39;t yet condensed, and this would have slowed down any Yeeted-Moon that was passing by, and maybe let it settle down into a stable orbit.

However, this theory got pretty much completely debunked because of one simple thing:

We went to the moon, and we grabbed some rocks, and then we took them back and we measured the fuck out of them.

We went to the moon, and we grabbed some rocks, and then we took them back and we measured the fuck out of them.

And the thing about that protoplantary disc that all the planets formed out of... it wasn& #39;t homogeneous.

Different elements and isotopes were located at different distances from the sun, and by measuring the ratios between them, we can figure out where something formed.

Different elements and isotopes were located at different distances from the sun, and by measuring the ratios between them, we can figure out where something formed.

So you could have three boring rocks in front of you:

one from earth, one from mars, one from venus

but stick them in a mass spectrometer, and you can figure out which is which, because of oxygen isotopes

one from earth, one from mars, one from venus

but stick them in a mass spectrometer, and you can figure out which is which, because of oxygen isotopes

and it turns out the moon formed... exactly where the earth did. It& #39;s not from the asteroid belt or farther out, it& #39;s the same as earth.

Which is again, very weird, because models of the protoplanetary disc don& #39;t show moons like The Moon forming!

Which is again, very weird, because models of the protoplanetary disc don& #39;t show moons like The Moon forming!

so then we have to figure out why it& #39;s there, and there& #39;s a couple theories, one of which is mostly accepted.

one of the theories is that it DID form out of the protoplanetary disc, it& #39;s just one of those really unlikely possibilities at the edges of the simulation.

This one has two problems:

angular momentum and the core of the moon.

This one has two problems:

angular momentum and the core of the moon.

generally all the planets are spinning because they formed out of a spinning disc, and therefore they& #39;re all spinning the same way... mostly.

It& #39;s a conservation of angular momentum thing: like when a spinning ice skater pulls in their arms, spinning faster

It& #39;s a conservation of angular momentum thing: like when a spinning ice skater pulls in their arms, spinning faster

a big spinning cloud of gas condensed down to some small rocks, and ended up spinning really fast because of it

The earth/moon system doesn& #39;t have enough angular momentum for it to still have the momentum from the formation. It should be much faster.

Now, it& #39;s slowing down over time, but it isn& #39;t old enough to explain why it& #39;s so slow now.

Now, it& #39;s slowing down over time, but it isn& #39;t old enough to explain why it& #39;s so slow now.

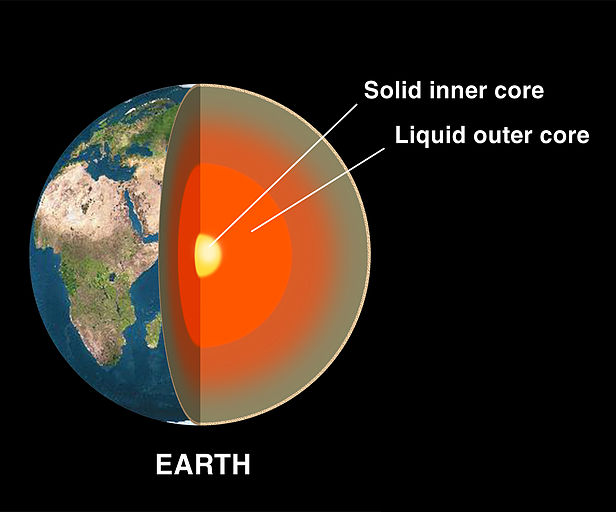

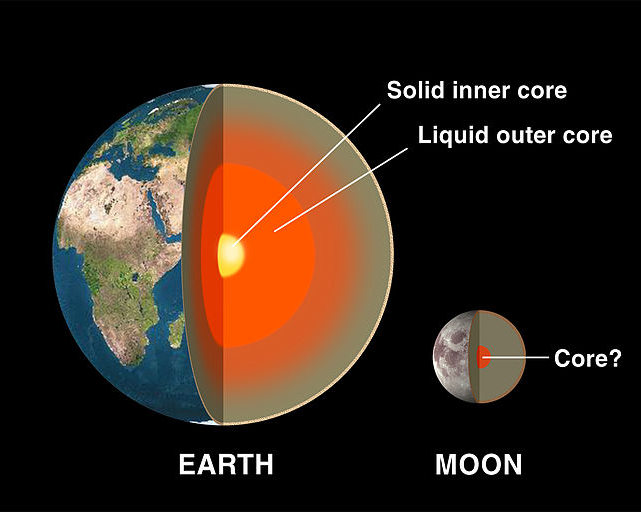

and also, the core: the earth has a big solid iron core. we think this started as a liquid iron core that slowly solidified... but we& #39;re not 100% sure.

(this is the inner core: there& #39;s a molten outer core around it)

(this is the inner core: there& #39;s a molten outer core around it)

and the combined inner core and outer core is about half the radius of the planet. it& #39;s huge.

And if the moon formed at the same place, under the same conditions, we& #39;d expect it have a similar core, right?

And if the moon formed at the same place, under the same conditions, we& #39;d expect it have a similar core, right?

EXCEPT we& #39;ve been able to do enough studies on moonquakes to see that the moon& #39;s core is tiny, compared to the Earth& #39;s.

That doesn& #39;t make sense if it did just accrete like the earth did, in the same area of the protoplantary disc

That doesn& #39;t make sense if it did just accrete like the earth did, in the same area of the protoplantary disc

So another theory for how the moon might have been created is fission (not that kind)

Early after the Earth formed, it was spinning rapidly, and maybe a big chunk of it just flew off because of the speed?

Early after the Earth formed, it was spinning rapidly, and maybe a big chunk of it just flew off because of the speed?

it was even suggested that maybe that& #39;s why there& #39;s a pacific ocean: that& #39;s where the big chunk of earth flew off, and now it& #39;s the moon.

Although now we know that the oceanic crust that makes up the pacific basin is really young, about 200 million years at most.

The moon has been around for longer than that, so no.

The moon has been around for longer than that, so no.

So about 4.6 billion years ago, the earth was about 90% as big as it is now, and something about the size of Mars (named Theia) smacked into us with a glancing blow.

Most of this planet merged in with the earth, but a lot of both planets just got thrown out into space

Most of this planet merged in with the earth, but a lot of both planets just got thrown out into space

and because of the angle of impact, this caused a long "arm" of material to come out of the molten planet tangle, which sheared off and stayed in the general area of the earth, slowly condensing into the moon.

this new moon was close in, but the tidal forces slowly pushed it out into the current orbit

This explains why the earth and moon are identical in isotope ratios, and why we have such a weird moon (since no other planets apparently got a good thwacking like we did). We& #39;re still working out the details, of course, some parts of the situation aren& #39;t nailed down 100%

like OK, we& #39;ve had a moon, but what about Second Moon?

because when you do a simulation of a mars-sized planet hitting a slightly-smaller earth, you usually get two moons, not one.

because when you do a simulation of a mars-sized planet hitting a slightly-smaller earth, you usually get two moons, not one.

one moon is possible, but unlikely. We clearly only have one moon (Cruithne doesn& #39;t count, damn it) so where& #39;s the other moon?

Either we then lost that moon, it merged with the earth or the moon later, or we& #39;re just really "lucky" and are in one of the unlikely 1-moon outcomes

Either we then lost that moon, it merged with the earth or the moon later, or we& #39;re just really "lucky" and are in one of the unlikely 1-moon outcomes

the isotope ratios being similar is what started this whole "the moon and the earth are from the same part of the protoplantary disc" idea but it also turns out they& #39;re TOO SIMILAR.

we expect that if Theia hit the Earth and merged, with parts of both getting tossed out and forming the moon, the moon would be more Theia than Earth in origin.

Theia would have had to have formed elsewhere, right?

but the isotope ratios between the earth and moon are too exact

Theia would have had to have formed elsewhere, right?

but the isotope ratios between the earth and moon are too exact

which suggests that either theia ended up mostly in the earth, instead of the moon (which is a whole & #39;nother mess of simulation unlikelyness) or that theia formed in the same area as the earth/moon and that& #39;s even less likely

so yeah.

We& #39;re pretty sure this is what happened... but we know there are some details we need to hammer down

We& #39;re pretty sure this is what happened... but we know there are some details we need to hammer down

and finally, the Gabon connection:

WHAT IF THERE WAS NO THEIA?

WHAT IF THERE WAS NO FAST-SPINNING PACIFIC-OCEAN-YEET?

NO CAPTURED DWARF PLANET?

NO UNLIKELY ACCRETION?

WHAT IF THERE WAS NO THEIA?

WHAT IF THERE WAS NO FAST-SPINNING PACIFIC-OCEAN-YEET?

NO CAPTURED DWARF PLANET?

NO UNLIKELY ACCRETION?

The moon is clearly made from the same material as the earth, but if it didn& #39;t come from the fast-spinning early planet or getting hit by another planet, how did it get up there in space?

have you ever tried to lift a big rock? they& #39;re heavy.

The moon is HUGE.

how do you get so much rock shoved up into space?

The moon is HUGE.

how do you get so much rock shoved up into space?

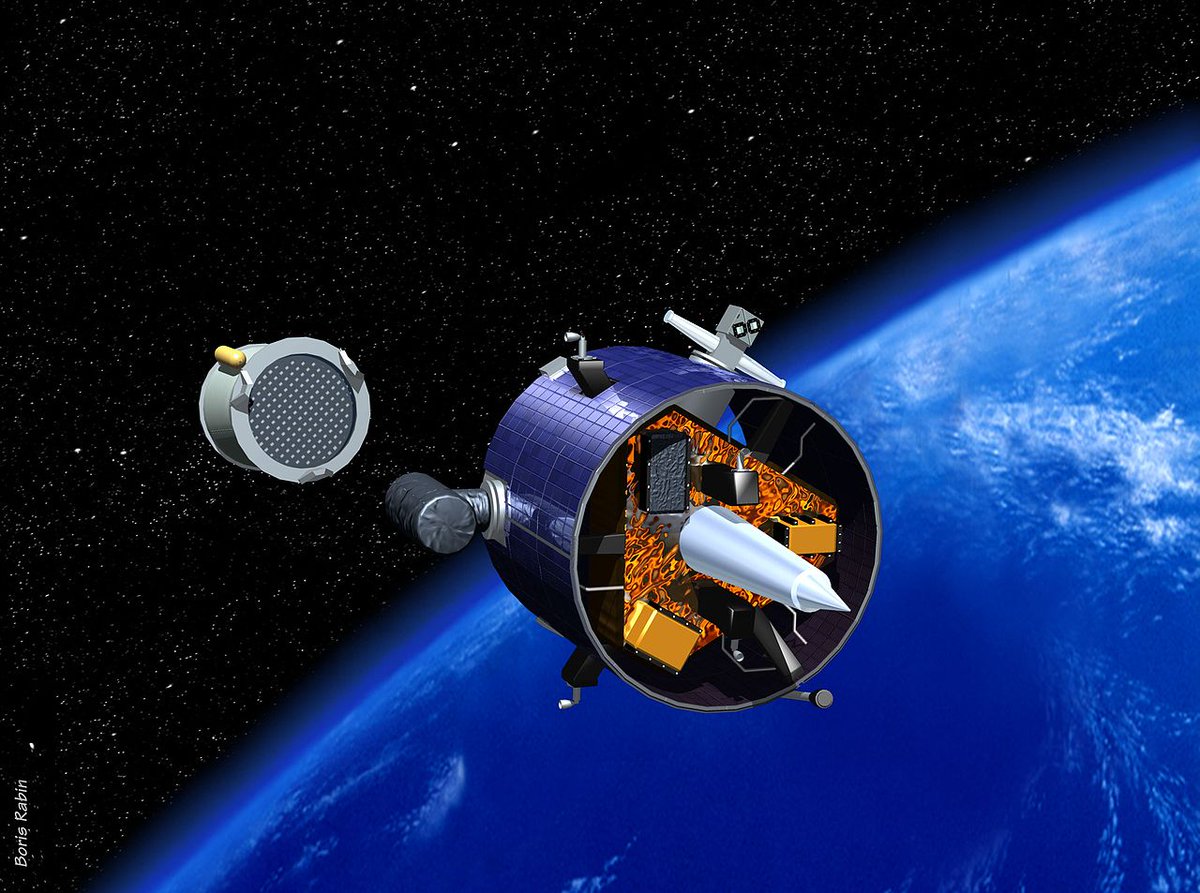

So in 1998 NASA launched the Lunar Prospector mission, which put a small probe into a lunar polar orbit, to measure the surface composition of the moon, looking for radioactive materials and lunar ice.

Because of how the moon rotates, the poles have craters which are forever in shadow. And it& #39;s long been suspected that there could be ice down there.

You can& #39;t have liquid water on the moon& #39;s surface, and the water vapor would torn apart by sunlight, and the hydrogen would float out into space.

But ice... you could have ice! other than the sun would melt it, then it& #39;d turn to water vapor, then poof goes the hydrogen

But ice... you could have ice! other than the sun would melt it, then it& #39;d turn to water vapor, then poof goes the hydrogen

but if you& #39;re in a crater that& #39;s always in shadow, there& #39;s no sun, the ice stays ice, and the moon might have ice that& #39;s been there basically since it formed.

Which& #39;d be cool to know about for a lot of reasons, thus Lunar Prospector.

Which& #39;d be cool to know about for a lot of reasons, thus Lunar Prospector.

correction: the ice wouldn& #39;t have been there since it formed, it& #39;d be deposited there from meteroids and comets.

in any case, Lunar Prospector did find polar ice, and we estimate there& #39;s about 800 billion gallons of it.

But it also found thorium, and a somewhat surprising amount of it.

But it also found thorium, and a somewhat surprising amount of it.

Thorium can also be used in nuclear reactions, and is also common in the earth& #39;s crust.

So in 2010, two Dutch scientists named Rob de Meijer and Wim van Westrenen suggested a different origin for the moon, inspired by both the Thorium concentrations on the moon and the Gabon reactors:

when the proto-earth was molten and rapidly spinning, the ratios of uranium-235 to U-238 were much higher, and there was lots of thorium in there too.

The spinning would have concentrated them in a ring around the equator, between the core and mantle

The spinning would have concentrated them in a ring around the equator, between the core and mantle

and if those concentrations were high enough, this could have caused a chain reaction, possibly one that served to keep intensifying itself as the heat generated (in the already very hot MOLTEN ROCK protoearth) concentrated it further

and eventually this may have reached a concentration that acted as a very poor (but fucking huge) nuclear bomb, and it literally EXPLODED THE MOON OUT INTO ORBIT

which I imagine freaked out any passing aliens.

You& #39;re flying around a solar system that has just finally formed a few rocky planets, still molten, no atmospheres or liquid water yet, it might be a nice place in a couple billion more years, and one of the planets nukes itself!

You& #39;re flying around a solar system that has just finally formed a few rocky planets, still molten, no atmospheres or liquid water yet, it might be a nice place in a couple billion more years, and one of the planets nukes itself!

were you wrong about it being lifeless and primordial? is there life here, or other alien ships visiting and taking shots at you?

Nope, just a weird planet that likes to do nuclear fission on its own. totally normal!

Nope, just a weird planet that likes to do nuclear fission on its own. totally normal!

anyway this theory is considered... quite unlikely.

But interestingly, it& #39;s not just a complete "WHAT IF?"

it& #39;s testable!

They predicted that there& #39;d be more helium-3 and xenon-136 on the moon if this is how it got there.

But interestingly, it& #39;s not just a complete "WHAT IF?"

it& #39;s testable!

They predicted that there& #39;d be more helium-3 and xenon-136 on the moon if this is how it got there.

this& #39;d be because those elements would be produced by the georeactor before it went boom, so if the moon was sploded into orbit, it& #39;d be full of & #39;em.

the only problem with testing this is that the solar wind already dumps tons of these isotopes onto the moon, so you& #39;d have to figure out how to compensate for the natural-solar-wind xenon-136 and helium-3, in order to measure how much had been there from the beginning

still, it& #39;s a neat, amusing idea.

anyway I& #39;m gonna stop ranting about natural reactors and the moon now.

If you wanna support me ranting about SCIENCE feel free to send me a dollar or two on ko-fi: https://ko-fi.com/fooneturing ">https://ko-fi.com/fooneturi...

If you wanna support me ranting about SCIENCE feel free to send me a dollar or two on ko-fi: https://ko-fi.com/fooneturing ">https://ko-fi.com/fooneturi...

or set up a Monthly Dollar on patreon: https://www.patreon.com/foone ">https://www.patreon.com/foone&quo...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter