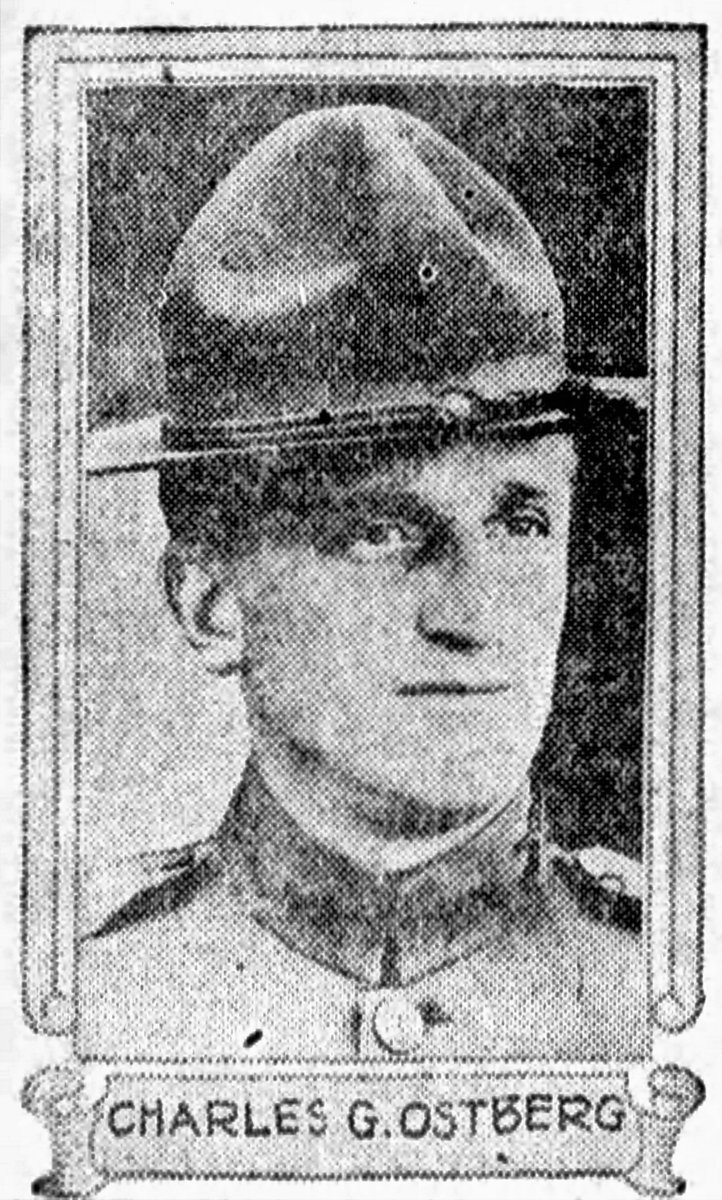

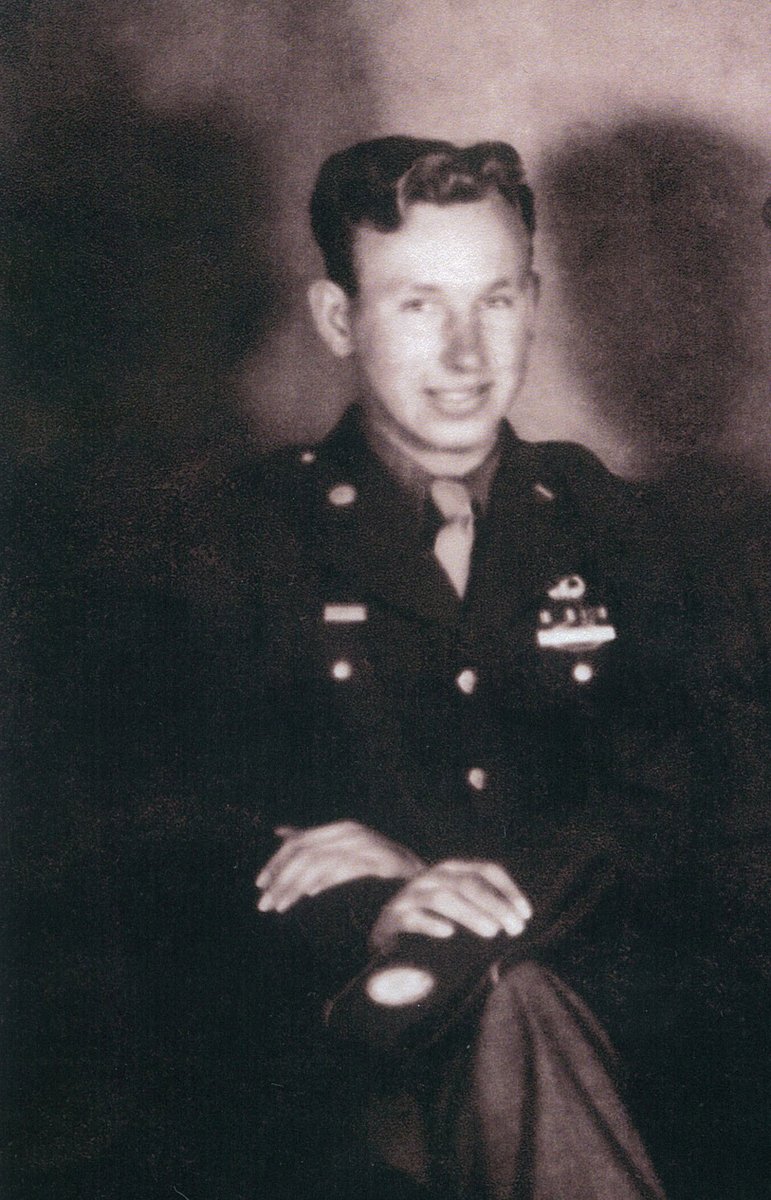

The Saga of Lieutenant Colonel Edwin J Ostberg and the family that gave a lot. Edwin Joseph Ostberg was born March 19th 1914 in New York, to Charles Gustav and Elizabeth Ostberg. His father, Charles Gustav, was a Swedish immigrant, and enlisted in the United States Army at /1

at the outbreak of WWI. He would go on to serve as a 1st Lieutenant with the 106th Infantry Regiment of the 27th Infantry Division, "O& #39;Ryans Roughnecks". On September 27th 1918 he was Killed in Action in an attack on the outer defenses of the Hindenberg Line. At the time of /2

his fathers death Edwin was just four years old. His mother suffered greatly from the loss, and died herself at quite a young age in 1937 having worked as a switchboard operator in New York, single-handedly raising her son to become the sort of man she had hoped he would be. /3

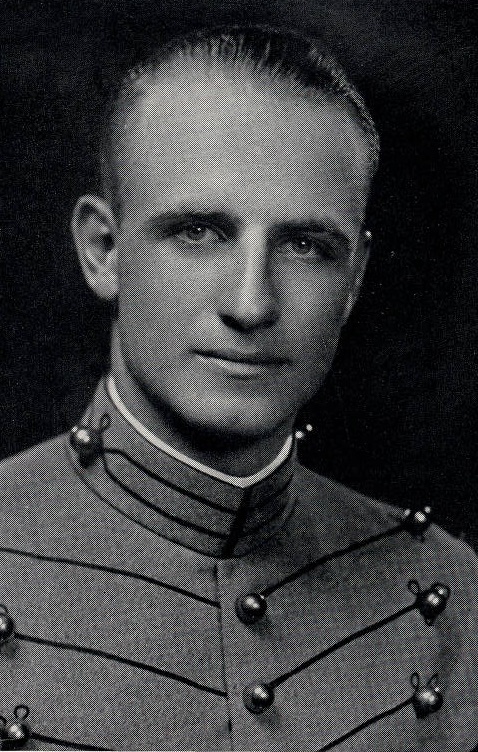

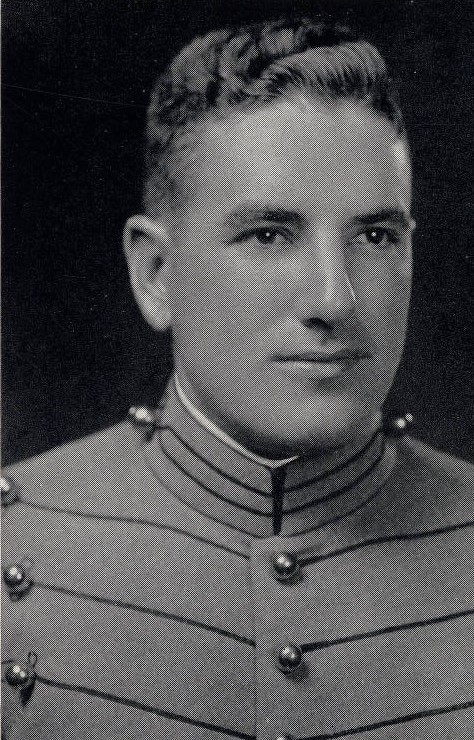

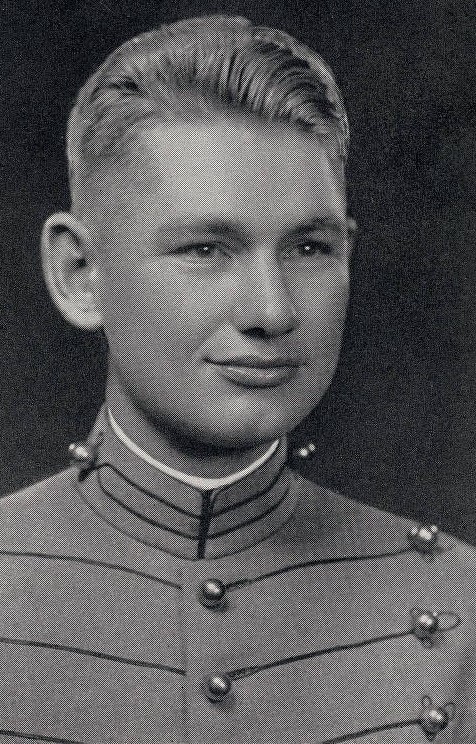

Wanting to be just like the father he had no memories of, Edwin applied for, and successfully enrolled at the US Military Academy at West Point, graduating in 1939. Graduating from West Point that same year was Robert George Cole, who later won the Medal of Honor with the /4

101st Airborne Division in Normandy, before being KIA on on September 18th 1944 near Best, Holland. Another to graduate that year was James Louis LePrade who was KIA in Noville, Belgium, again with the 101st Airborne Division. All three, including Edwin, had been Battalion /5

Commanders in Parachute Infantry Regiments in WWII. Following various appointments with the US Army, Edwin volunteered to serve as a Paratrooper, and was later assigned to a post Commanding the 1st Battalion in the newly formed 507th Parachute Infantry Regiment. Prior to /6

this, and before the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, he had married his sweetheart Marjorie, and together they took the journey through his military career. On March 11th 1942 he was stationed at Fort Benning, Georgia, to undergo jump training with hundreds of other recruits. /7

That day his first and only child, Betsy, was born. Almost exactly around the time of her 2nd Birthday, (the now) Lieutenant Colonel Edwin J Ostberg and his Regiment were in transit from Northern Ireland to England. Soon they would be camped in the grounds of Tollerton Hall, /8

Nottinghamshire, to be their base for nearly 3 months as they prepared to play their part in the invasion of Normandy. The photo shows the Regiments senior Officers at Tollerton, Ostberg is lower left. On 6 June 1944 Ostberg jumped with his 1st Battalion over Normandy from /9

aircraft of the 442nd Troop Carrier Group flying out of RAF Fulbeck, in Lincolnshire. Having landed in the wrong place, Ostberg was with Lieutenant Colonel Art Maloney (Regimental XO) and some 150 who converged on the rail-line running behind La Fiere with Brigadier General /10

James Gavin. Gavin wanted to move on La Fiere immediately. Seeing that the Bridge and Manoir at La Fiere was under attack by 1/505 under Major Kellam (and as we know now various others) he took a group of 75 men, including Ostberg, further South along the rail-line to Chef Du /11

Pont, where another crossing of the Merderet was a Divisional objective. Moving rapidly on the Bridge itself before the increasingly present German occupiers could organise a defence, Ostberg led the large Group less one Squad and attacked. German Machine-Guns on the opposite /12

bank opened up, hitting Ostberg in the chest, the impact throwing him off the Bridge (which, at the time, had no sides/railings) into the Merderet below. Three men, Robert Vannatter (photograph), Roy Creek, and Glen LaPine, helped Ostberg from the river, and back to a safer /13

spot. Ostberg was later evacuated, having suffered a collapsed lung, and wounds to his arm. On account of his injury, it was advised that he no longer serve in a Parachute unit. In July 1944 the 507th PIR returned to Tollerton Hall following circa 35 days of Combat in France /14

and began to recover. Personnel were sent out on furlough, and casualties began to return. At this time, Ostberg was recovering with the 94th General Hospital. In August 1944, Ostberg was relieved of his Command of the 1st Battalion, and sent back to the U.S for a post in the /15

ZI. Just prior to doing so, and slightly prior to his Regiments reassignment to the 17th Airborne Division, he returned to Tollerton Hall, and stood atop the balcony overhanging the Halls main door, and addressed his Battalion. Fundamentally, this was a goodbye. Ostberg had /16

the respect of Brigadier General Gavin, who corresponded regularly with his daughter Betsy in the post-war years. So keen was Gavin to have an Officer of his calibre back with the Division that in November 1944 he facilitated his return to the Division as part of his staff. /17

With the Battle of the Bulge around the corner, Ostberg was back where the action was, and when on January 4th 1945 when the CO of the 2nd Battalion, 325th Glider Infantry Regiment, Major Richard M Gibson was wounded, Gavin sent Ostberg forward to take over his Battalion. /18

On February 2nd 1945 the 325th moved out of the Hunniger Wald on the Belgian/German border and commenced an attack on the Siegried Line at Neuhof and Udenbreth with tank support. The 1st Battalion suffered such a number of casualties that when it finally breached the German /19

defences on the Siegfried line itself, it didn& #39;t have enough men to clear the village, and was in danger of being pushed back. Here the 1st Battalion and its tank support halted, as Colonel Billingslea ordered the 2nd Battalion under Ostberg to push through their lines. /20

Reaching the crossroads in the center of the town, Ostberg spotted the stationary US tanks and seeing German infantry on the move in the distance, mounted one and began operating the turret-mounted .50cal MG. No sooner had he started firing when an 88 smashed into the tank, /21

throwing Ostberg clear. He was killed immediately, with shrapnel having ripped through his neck to the point of near decapitation. Days later the 82nd was relieved by elements of the 99th Infantry Division and trucked to the rear. In a letter to Ostbergs daughter, /22

General Gavin said that it was his belief that had Ostberg survived that day, he& #39;d have survived the war. Fighting for the 82nd seldom got as severe again for the remainder of WWII. I have mixed opinions on Ostberg and his actions, and would welcome the thoughts of others. On /23

two occasions he put himself in the sort of position that, IMO, a Lieutenant Colonel perhaps shouldn& #39;t have been. The same applies to a number of others in similar command positions in the Airborne Divisions in WWII, such as LTC Robert Cole. Whilst evidently courageous, do

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter