THREAD. 1) My book ‘War Veterans and Fascism in Interwar Europe’ explains whether and how ex-combatants became members and supporters of fascist movements and regimes after the First World War. This question has been the matter of discussion by historians for a long time...

2) Following George L. Mosse’s thesis of the postwar “brutalization of politics”, historians pointed out the high levels of involvement of veterans in right-wing paramilitary organizations and political violence.

3) These facts made historians believe there was some sort of essential connection between veterans and the fascist ideology and movements.

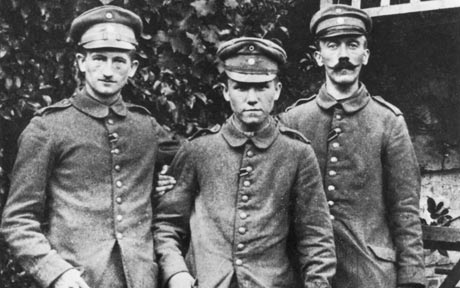

After all, Hitler, Mussolini and most prominent fascists were former soldiers, right?

After all, Hitler, Mussolini and most prominent fascists were former soldiers, right?

4)But other historians have demonstrated that numerous veterans joined pacifist and democratic movements in many countries. Veterans also created internationalist organizations striving for cooperation and peace. The majority of exsoldiers never joined fascist parties.

5)This struck me as a historical paradox:

While most fascists were veterans… most veterans were not fascists.

The “brutalization” thesis seemed to work in some countries but not in others.

So how to resolve the contradictions and endless arguments around it?

While most fascists were veterans… most veterans were not fascists.

The “brutalization” thesis seemed to work in some countries but not in others.

So how to resolve the contradictions and endless arguments around it?

6) In my research I decided to transcend the “brutalization” paradigm and use an entirely new approach to examine the relationship between veterans & fascism. I used two methods:

7) First, I looked at “veterans” as a constructed idea, the object of political struggles and symbolic appropriation.

8) Second, to ensure the validity of my interpretation in different “national cases”, I went beyond the common “comparisons” between countries. I applied a transnational perspective instead: focus on transfers and networks.

9) The key question is, how did veterans ever become associated to far-right politics in the first place? This outcome was never predetermined. In 1918, millions of Great War veterans were rather seen as a potentially social-revolutionary group, as the Russian revolution showed.

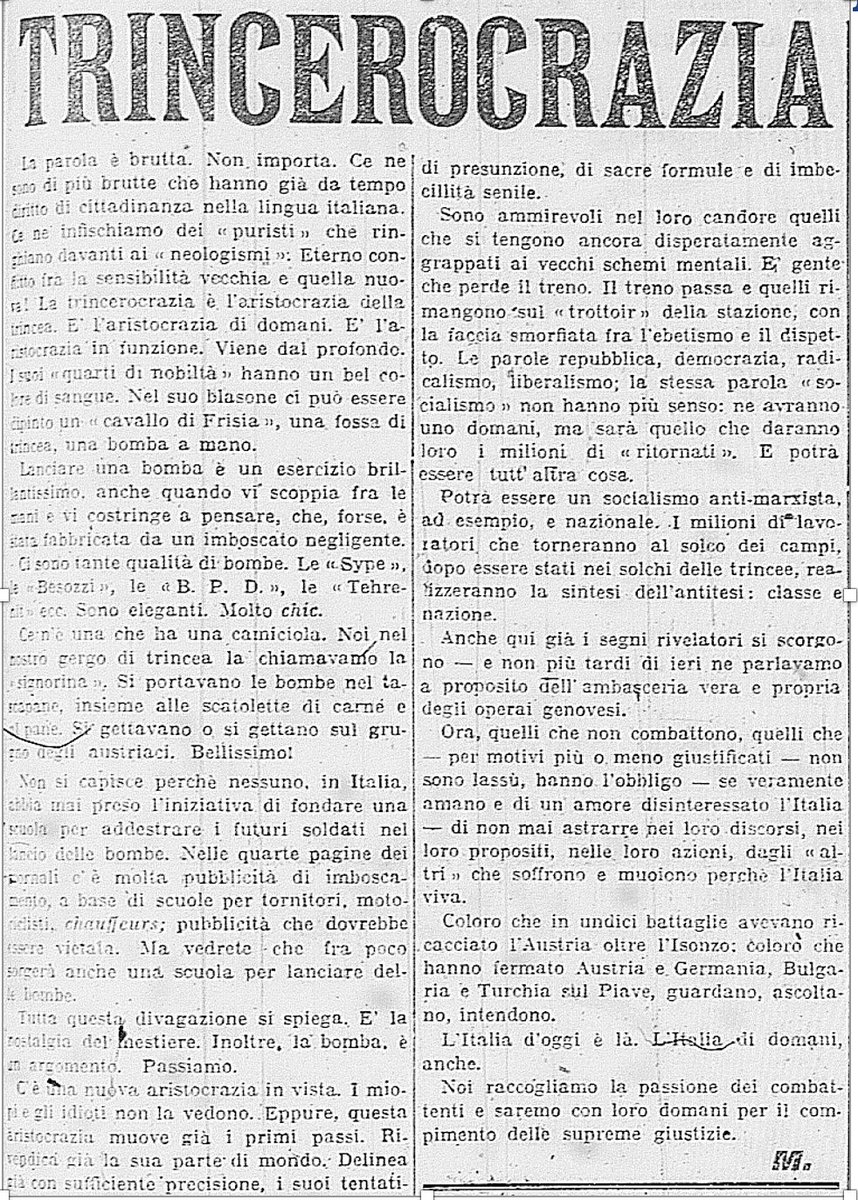

10) I demonstrated how symbolic appropriation of the “veteran” symbol took place in Europe during 1919. It was a transnational process, but had the clearest consequences in Italy, where Mussolini and the fascists strived to gain veterans to their ranks.

11) Thus a stereotype formed: the “antibolshevik veteran”. This stereotypical perception of veterans was closely associated to the rising Italian fascist movement, but disseminated transnationally, starting to influence politics in countries such as Germany and France.

12) When fascists took power through the March on Rome (1922), the stereotype became a fully-fledged political myth.

13) It’s what I called the “Myth of the Fascist Veterans”. A narrative that presented fascists as veterans who had smashed the Bolshevik revolutionary threat, restored “victory” and obtained a leading role in their country. This narrative circulated transnationally.

14) In the 1920s under Mussolini, Italian veterans experienced forced fascistization and a loss of rights and liberties. But the Myth of the Fascist Veterans was embraced by right-wing groups in Germany (Stahlhelm) and France (Faisceau, etc.).

15) Fascism gained popularity. It certainly attracted some veterans. But people generally believed not only that fascists were veterans, but also that veterans were potential fascists.

16) In the 1930s, history got complicated. Fascism took advantage of international veterans’ networks to expand its influence in Europe. Nazi Germany followed a similar path, Nazifying veteran politics. Yet antifascists tried to break the fascist hegemony over the veteran symbol.

17) However, fascists and Nazis successfully manipulated veteran politics and discourses. The Spanish and Ethiopian Wars renewed fascist myths about the war experience. In France, the veterans’ embrace of authoritarianism was largely a result of fascist influence.

18) By the late 1930s, a totalitarian model of veteran politics had developed in Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany. Francoist Spain fully embraced it with its veterans from the civil war. After June 1940, Pétain resorted to the veterans’ support in another dictatorship: Vichy France

19) In conclusion, not “brutalization”, but the manipulation of a complex of transnational, culturally-constructed and mythical ideas of the war veteran(s) shaped the historical relationship between veterans and fascism.

21) By 1940, even if most individuals who had fought in the First World War had never been the violent anti-democrats, ultra-nationalist anti-Bolsheviks that fascism claimed, the symbol of the fascist and the symbol of the veteran had merged in the minds of many Europeans.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter