I& #39;ve been working on a post about disproportionate impact since before the lockdown. We now have an example where both the disease and the response will disproportionately impact low-income BIPOC. Is our mobility response proportionate? https://bike-lab.org/2020/04/14/disproportionality/">https://bike-lab.org/2020/04/1... 1/

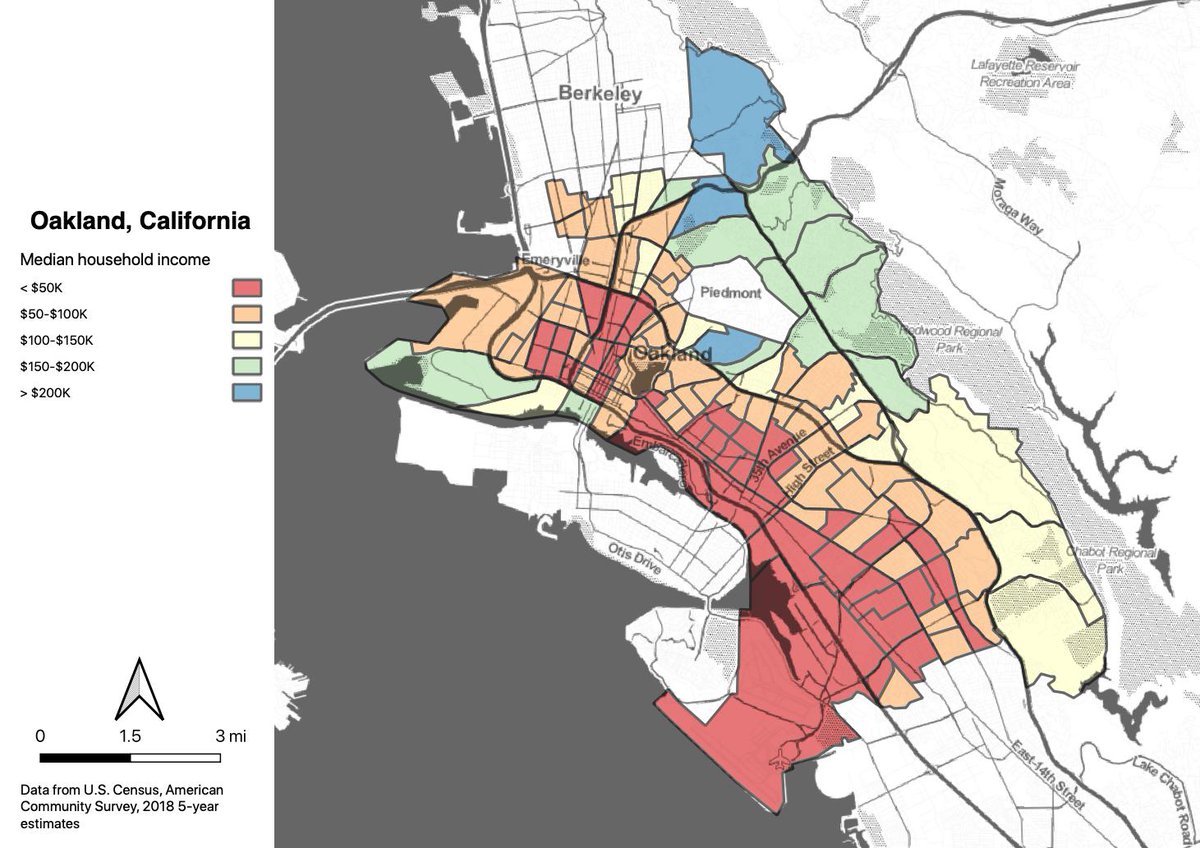

People are learning more about redlining. Those government-sponsored racial divisions still affect every societal ill. See the post for a set of maps; this one is median income, which looks just like the 1937 map. Health, education, crime are the same. 2/

We already see that BIPOC are substantially more likely to die from COVID-19, and we will later discover that are more likely to have lost their jobs, more likely to have lost their housing, more likely to have had interruptions in their education, and so on. 3/

All of it is sadly predictable, because that’s the way the system works. 4/

Disadvantaged communities are disproportionately impacted by all our societal harms. So the fact of disadvantage cannot be used as justification for a particular intervention, unless it is specifically rooted in addressing societal harms experienced by that community. 5/

@untokening& #39;s white paper on Mobility Justice and COVID-19, which you should read, has a number of points which are relevant to mobility in Oakland, including the Oakland Slow Streets program. 6/

"Do not plan future projects at a time when equitable public participation is impossible." Russo says "we& #39;ve already studied" these streets. But the bike plan doesn’t specify how they will be changed. It certainly doesn’t specify that they will be closed to through traffic. 7/

And while this program is specified as an emergency measure, it seems likely that it will be used as a prototype for more permanent street diverters, the sort of tactical urbanism that Russo championed in NYC. The communities haven’t really been consulted. 8/

Schaaf asserted that Oakland will not be issuing citations on Slow Streets. But Oakland has a decades-long history of being unable to control OPD, and in particular, being unable to stop OPD from persecuting Black people. And Gallo is explicitly calling for more policing. 9/

"Direct public funding to community bicycle shops that can distribute vehicles and provide repair at a neighborhood level." Here’s something Oakland really could be doing. We have community shops like Cycles of Change who could be funded to distribute bikes. 10/

The problem with disproportionate impact—besides its existence—is that its ubiquity limits its usefulness as a tool for analysis. If BIPOC communities are disproportionately impacted by everything, the fact of that impact can be used to justify practically anything. 11/

In Oakland, BIPOC bikes/peds are more likely to be hit by a car. But that fact is not a blanket justification for every possible intervention to protect pedestrians and cyclists, because they are also more likely to be impacted by every other social ill. 12/

West Oakland is the worst place in the East Bay for childhood asthma. Traditional bike advocacy argues that therefore, we should install more bike infrastructure in West Oakland, to increase physical activity levels and give people transportation options. 13/

But the reason childhood asthma is high in is primarily because of high levels of particulate pollution from the port and the freeways. Bike infrastructure isn’t going to fix those problems, and riding around in air with high levels of particulates could make asthma worse. 14/

And as I’ve noted before, the pairing of bike infrastructure with economic development in order to build political capital has led to bike infrastructure becoming associated with displacement and gentrification, with impacts primarily borne by low-income BIPOC. 15/

Bike advocacy has articulated a specific goal: a connected network of low-stress bikeways. Advocates are generally willing to assume that this goal is morally neutral and not connected to societal systems of oppression. 16/

But when you have already chosen your goal, and then you advocate for it by claiming it will address societal systems of oppression, you’re not elevating the struggle of oppressed people. You’re appropriating it. 17/

You have to begin with the lived experience of oppressed peoples, and give them agency in finding solutions. How do parents in West Oakland feel about high asthma rates in their children? How important is the problem to them? What would they like to see change? 18/

I don’t know the answers, but if you’re claiming to address the disproportionate impact of childhood asthma, you must ask those questions before you suggest a solution. And you must be willing to accept that the visions of the people affected may differ from yours. 19/

Low-income BIPOC are being disproportionately slaughtered by a global pandemic. They are also at disproportionate risk of long-term financial hardship due to the economic shutdown. Both the disease and the response disproportionately impact those communities. 20/

Is shutting down streets so that people can jog and walk their dogs a proportionate response? 21/

I was today years old when I found out that EBT cards can’t be used to buy groceries online. My white, professional-class family never had to interact with America’s social welfare systems, or to experience the ways that they contribute to oppression. 22/

In the age of COVID-19, they’re reducing access to healthy food and increasing exposure to risk of infection among already-vulnerable populations. And while I get to sit home and write grant proposals and blog posts, working-class people are out there getting exposed. 23/

I love riding bikes (and unicycles). It would be really hard on me if the U.S. were to decide to restrict outdoor recreation as Spain and Italy have. But I have to contextualize that as part of the crisis we’re in. 24/

My frustration at not being able to ride or walk the way I might want to is nothing compared to having to deal with housing insecurity, food insecurity, and the threat of serious illness and death. If I have to stay shut in for a few weeks, I can deal with it. 25/

I’m not saying that Oakland shouldn’t close streets to cars, but I am saying that it doesn’t feel like a proportionate response. It centers the needs of people like me who have the freedom to stay at home, instead of centering the needs of the most vulnerable. 26/

It’s not the only thing the city has done in response to the crisis, but it is the only one which has involved an in-person press conference, and it’s the only one which other cities are being pushed to emulate. That says a lot about who city leaders are speaking to. 27/

My challenge to advocates who want to address disproportionate impacts is to flip your script. Don’t start with a proposal; start by talking to the impacted groups. Try to understand their experiences and their priorities. 28/

Listen to what they have to say, learn about how they’re already coping, and see if you can figure out how your idea fits into their framework. If you do it the other way around, you’re contributing to their marginalization. 29/29

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter