The way we think about trends is broken and it& #39;s affecting our reaction to COVID-19. We can learn from the research on prison history and mass incarceration. THREAD!

Point 1: When reviewing COVID-19 data, we put too much emphasis on national-level, aggregate trends (how many deaths in the US v broken down by state). But national-level trends can be driven by one or two states (like New York in this case). /2

When the national incarceration rate went down in 2011, this was big news. But the decline was mostly due to cuts to California& #39;s prison population. Many other states *increased* their prison populations. /3

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/15564886.2015.1078185?journalCode=uvao20">https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/1...

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/15564886.2015.1078185?journalCode=uvao20">https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/1...

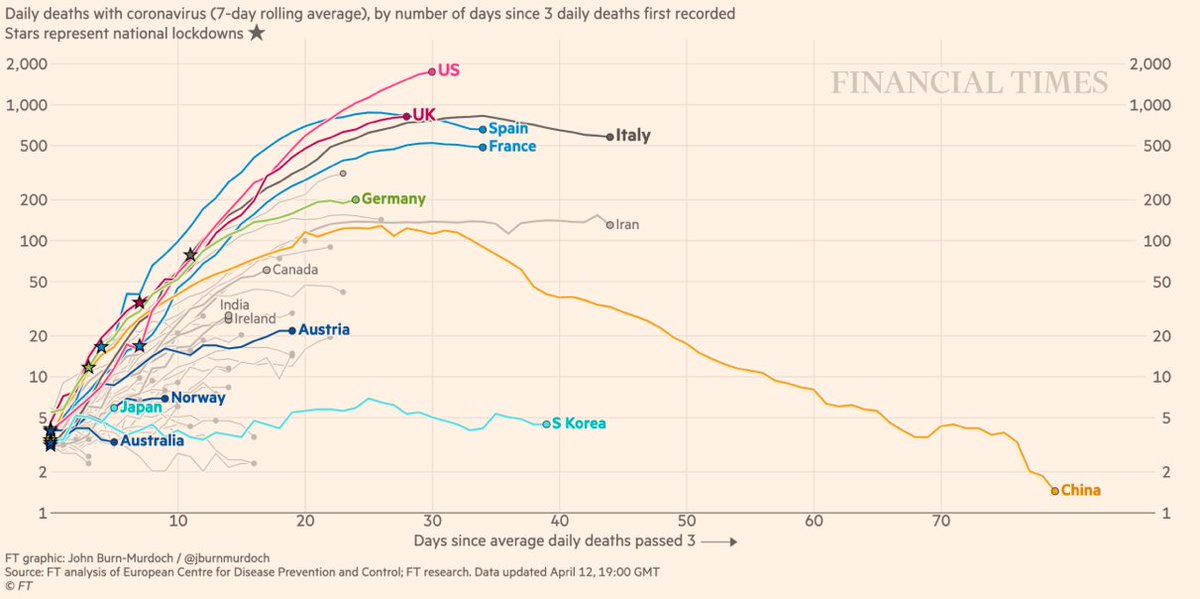

National-level data also leaves out counter-trends and pockets of slow, gradual change. (FT map below.) /4

While the rest of the country was celebrating prisoner rehabilitation, building "correctional institutions," and changing the name of guards to "correctional officers, the South still relied on plantation-style prisons (like Cummins Farm below) that replicated slavery. /5

By the time national-level trends seem like they are wrapping up, these lagging states (or areas of states, like rural areas) can be just getting going on the trend. /6 https://twitter.com/DrRobDavidson/status/1249679726538625026">https://twitter.com/DrRobDavi...

In the 1970s, Arizona hopped on the rehabilitative band wagon. This was around the time the California--which led the charge in favor of rehabilitation--was rejecting rehabilitation in favor of punishment. /7 https://www.sup.org/books/title/?id=17521">https://www.sup.org/books/tit...

When these lagging states get going on the seemingly passé trend, they can be facing different conditions. Federal funding for testing is ending now but some states that didn& #39;t see a lot of cases initially (and some pockets like prisons) are seeing accelerating numbers of cases.8

This gets me to Point 2: We put history into boxes. In thinking about COVID-19, we are quick to do the same (e.g., talk of the "peak" or when this is all going to end and get back to normal). /9

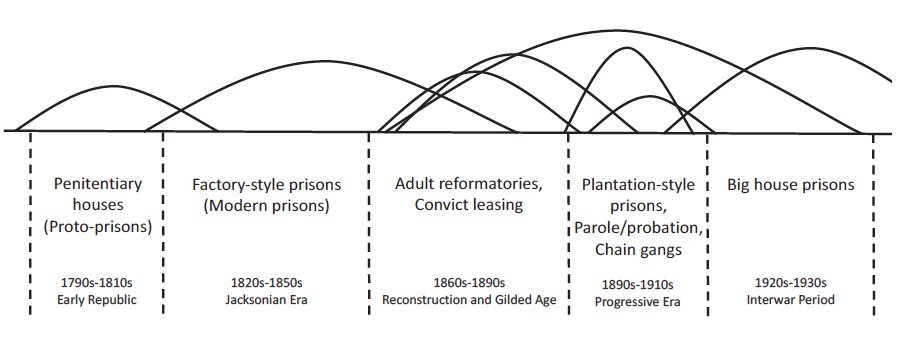

Here& #39;s an example from prison history. When talking about the rise of new types of prisons, we put them into periods, e.g., 1790-1820 or 1890-1920. But the rise and spread of these prisons usually begins before and ends after these periods. /10

This is important bc late adopters (or late-emerging COVID-19 hotspots) face different conditions than innovators and early adopters (the places that saw a lot of cases early on). /11

In the case of prison adoption, different factors drove adoption in the 1810s/20s v. 1840s/50s. The former were driven more for ideological/penological reasons. They had a real need (what they saw as need) for prisons. /12 https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/lasr.12136">https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/1...

The latter were not. They were states that didn& #39;t exactly need a particular model of prison, or even a prison generally. They adopted these prisons to look legitimate. (This is not unique to prison adoption, btw. See link below for ex.) /13

https://www.jstor.org/stable/4623368?seq=1">https://www.jstor.org/stable/46...

https://www.jstor.org/stable/4623368?seq=1">https://www.jstor.org/stable/46...

Again, late-stage COVID-19 hotspots will be facing different conditions than early stage. Perhaps more prepared, more available data, know what to expect. But also already drained, fewer resources, etc. Plus, pre-existing differences like possibly less infrastructure. /14

Perhaps most importantly, though, our tendency to box history means people will be too quick to say this is "over." They& #39;ll do this when it& #39;s over in NYC and Seattle, but it won& #39;t be over for Mississippi or Iowa or prisons and other places flying under the radar right now. /15

This is why I& #39;m so worried about all this talk of hitting the "peak." The data seem to be driven mostly by NYC (like California in our national prison population ex). But other places haven& #39;t peaked yet. /16

And the big consequence is if we loosen up social distancing too early and "reopen" the country bc the places getting the attention now are getting better--and the places that are several weeks behind don& #39;t have many visible cases yet. /17

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter