Today’s tour takes us to the first of the American modernism galleries on the ground floor of the East Building, gallery 106C. #MuseumFromHome

See a list of all the works in the gallery: http://go.usa.gov/xvWv3 ">https://go.usa.gov/xvWv3&quo...

See a list of all the works in the gallery: http://go.usa.gov/xvWv3 ">https://go.usa.gov/xvWv3&quo...

Our tour is led by Catherine Southwick, curatorial associate in the Gallery’s department of American and British Paintings.

Here& #39;s Catherine giving a talk at a past #NGAnights.

Here& #39;s Catherine giving a talk at a past #NGAnights.

This gallery includes work by artist and teacher Robert Henri, known as the founder of the so-called Ashcan school of urban realism. Henri was a contemporary of John Sloan and the teacher of the two other artists featured in this gallery, George Bellows and Edward Hopper.

The works exemplify the range of personalities and styles that emerged from the American modernists first inspired by Henri.

Henri urged them to reject the prevailing taste for pleasant, uncontroversial subject matter in favor of grittier depictions of contemporary urban life.

Henri urged them to reject the prevailing taste for pleasant, uncontroversial subject matter in favor of grittier depictions of contemporary urban life.

But Henri was not interested in prescribing a specific style. He instead wanted his students to discover their own unique strategies for representing modern experience.

“Do whatever you do intensely,” he said to his students.

[John Sloan, detail of "Robert Henri, Painter, 1931]

“Do whatever you do intensely,” he said to his students.

[John Sloan, detail of "Robert Henri, Painter, 1931]

Henri’s urban snowscape is fundamentally different from those by impressionist artists of the same period.

[Camille Pissarro, “The Boulevard Montmartre on a Winter Morning,” 1897, @MetMuseum]

[Camille Pissarro, “The Boulevard Montmartre on a Winter Morning,” 1897, @MetMuseum]

Henri depicted an unremarkable side street near his studio, rather than a grand view of a major avenue. There is nothing narrative or sentimental about the image, and the somber palette creates an oppressive atmosphere.

Rather than representing the picturesque quality of snow, Henri’s snow is streaked with mud and gravel—the reality of snowfall in a big city.

Though this painting did sell at an exhibition in 1902, at the end of that year Henri resolved to focus on portraiture due to his overall lack of success with his city scenes.

As a portrait painter, Henri remained true to his belief in “art for life’s sake,” depicting sitters from varying backgrounds.

[“Catharine,” 1913]

[“Catharine,” 1913]

Learn more about Henri and explore several stunning examples of his portraits in the Gallery’s collection including “Young Woman in White” (1904) in our "American Paintings, 1900–1945" Online Edition: http://go.usa.gov/xvWdC ">https://go.usa.gov/xvWdC&quo...

John Sloan, along with fellow newspaper illustrators William Glackens, George Luks, and Everett Shinn, was encouraged by Henri to move from Philadelphia to New York around the turn of the century and become painters.

[Photo of Shinn, Henri, and Sloan from the @ArchivesAmerArt]

[Photo of Shinn, Henri, and Sloan from the @ArchivesAmerArt]

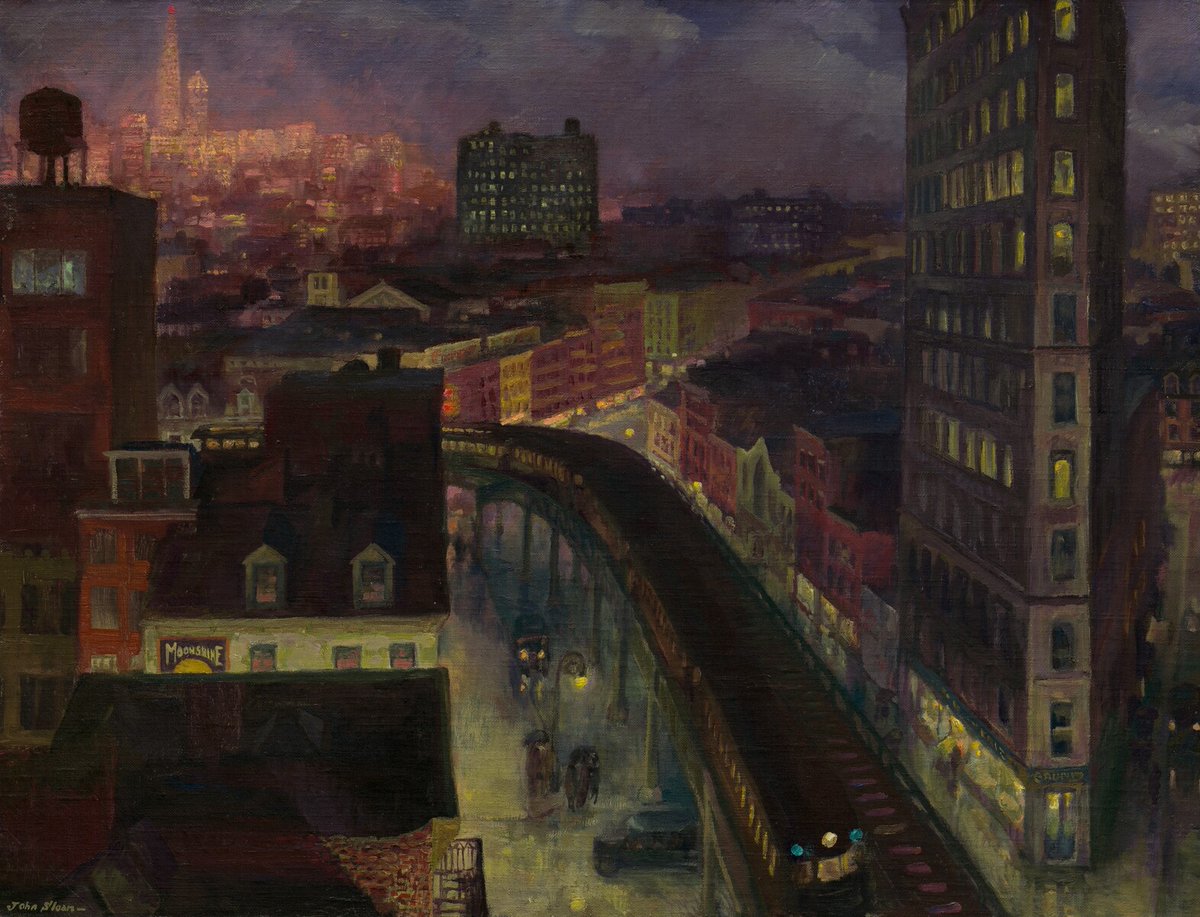

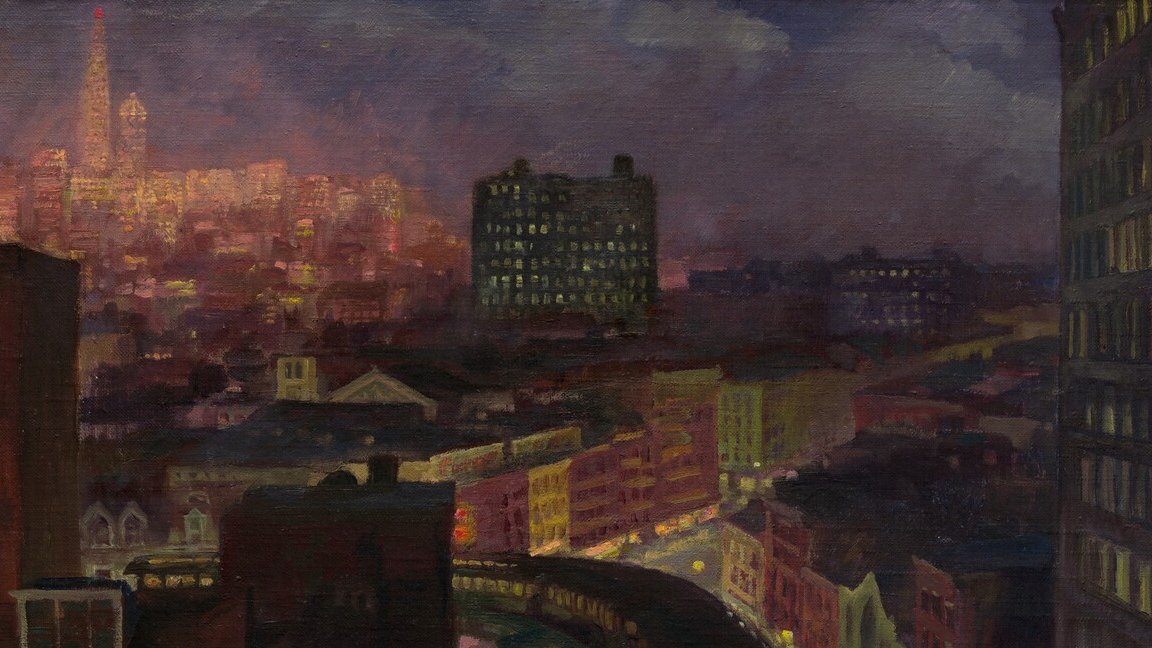

Gallery 106C includes Sloan’s “The City from Greenwich Village” (1922).

In Sloan’s own words, “the picture makes a record of the beauty of the older city, which is giving way to the chopped-out towers of the modern New York.”

In Sloan’s own words, “the picture makes a record of the beauty of the older city, which is giving way to the chopped-out towers of the modern New York.”

The view is from the roof of Sloan’s studio apartment and shows lower Sixth Avenue on a rainy evening.

An elevated train is barely contained within Sloan’s composition, about to move beyond the bottom edge of the canvas.

An elevated train is barely contained within Sloan’s composition, about to move beyond the bottom edge of the canvas.

From the artist’s viewpoint, we look over the Greenwich Village rooftops to the brilliantly illuminated skyscrapers, silhouetted on the horizon.

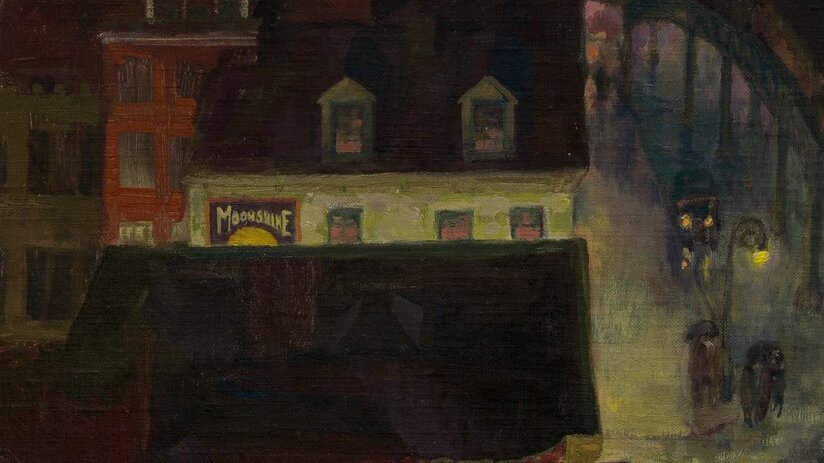

Notice the Moonshine advertisement (a fictional brand) on a building at the lower left. The cropped moon graphic wittily suggests what the city’s electric lighting obscures: natural moonlight.

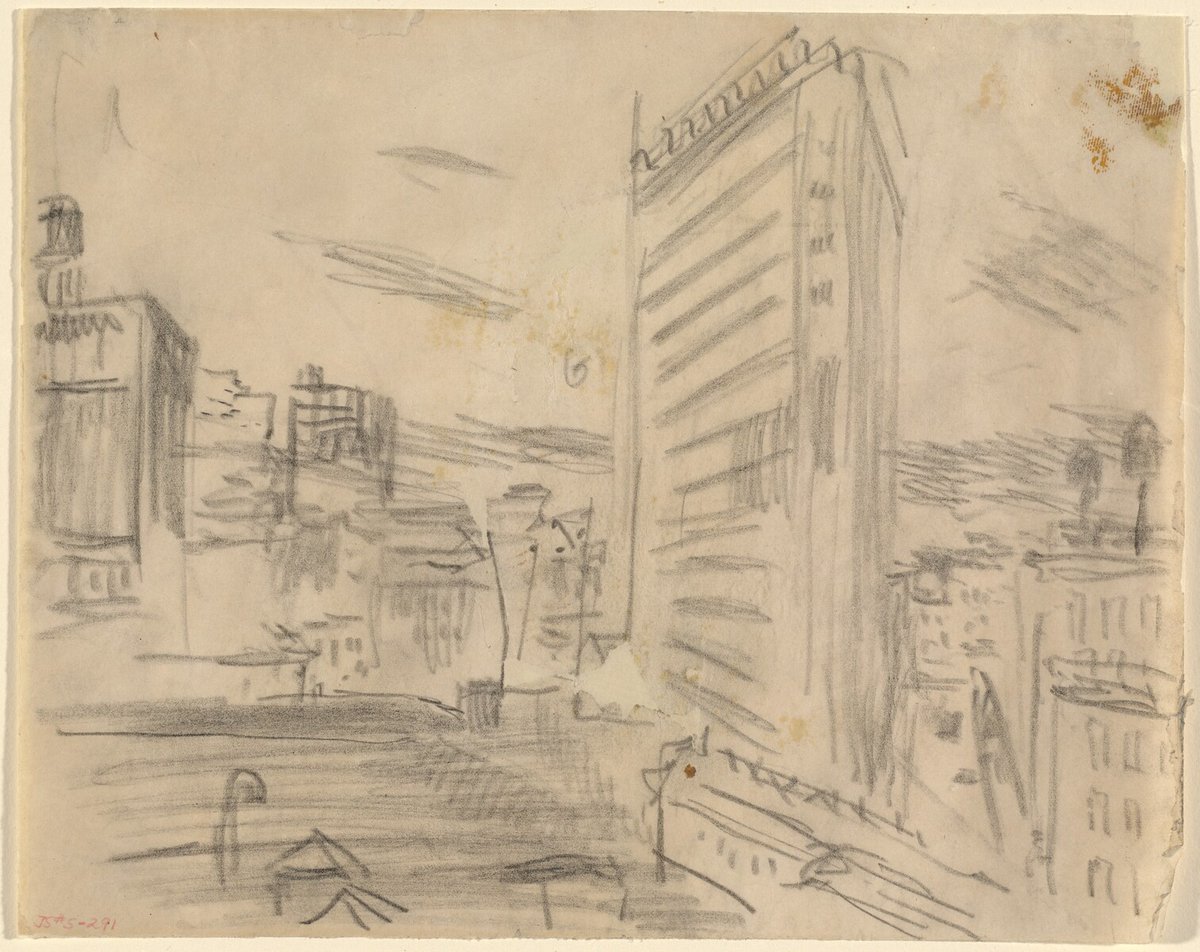

The Gallery’s collection also includes sketches made for the painting, including this one “Study for ‘The City from Greenwich Village,’ I” (c. 1922).

Explore all of the studies: http://go.usa.gov/xvWEB ">https://go.usa.gov/xvWEB&quo...

Explore all of the studies: http://go.usa.gov/xvWEB ">https://go.usa.gov/xvWEB&quo...

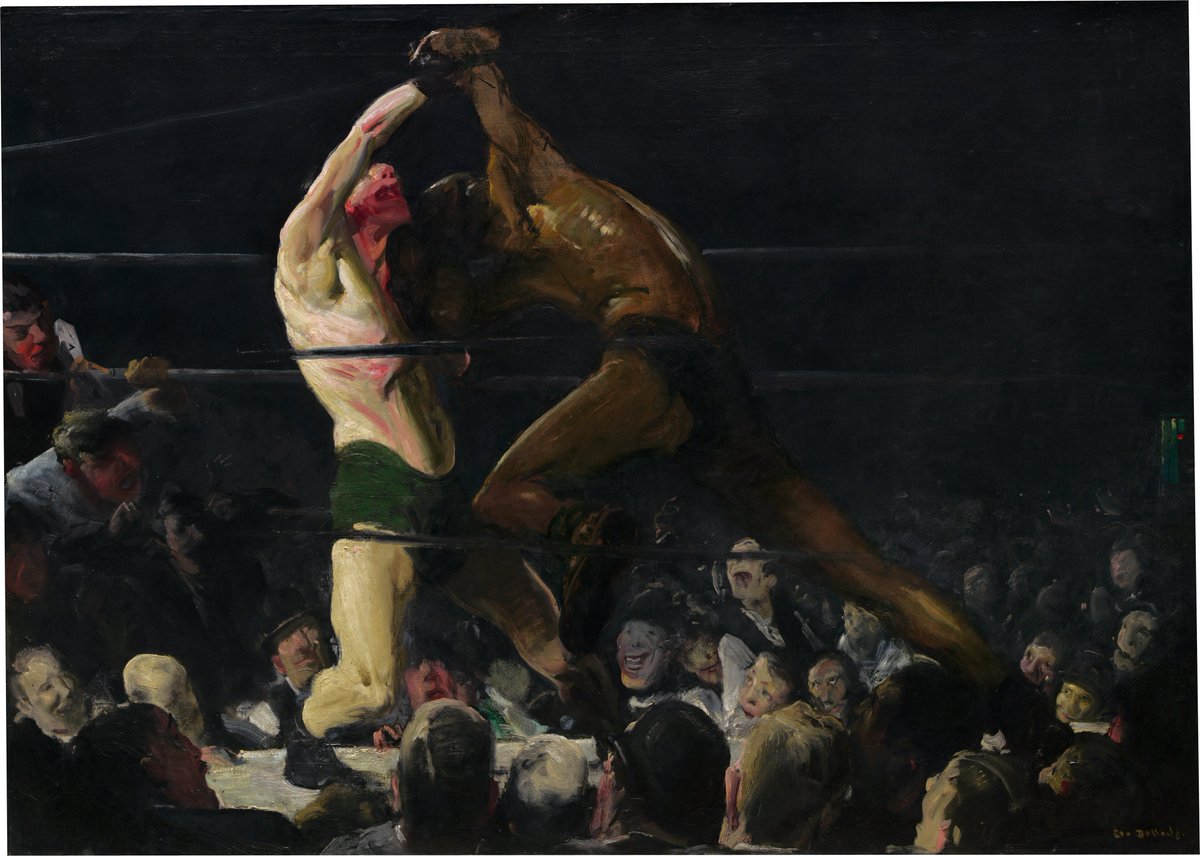

Now, we move to the work of George Bellows and the painting that has served as the cornerstone of the collection of American modernism at the Gallery, “Both Members of this Club” (1909).

Chester and Maud Dale were influential founding donors to the Gallery. At the time of our opening in 1941, works by living artists were officially not accepted into the collection. 20 years had to pass following an artist’s death for their works to be “eligible” for inclusion.

Dale, realizing that the 20-year anniversary of George Bellows’s death was approaching in 1945, purchased “Both Members of this Club” in late 1944 and donated it to the Gallery in January 1945 so that it could join the collection at the earliest possible moment.

“Both Members of This Club” is the third and largest of Bellows’s early prizefighting subjects. As public boxing matches were banned in New York state, the title refers to private athletic clubs’ practice of introducing the contestants to the audience as “both members.”

“Both Members of This Club” was likely an allusion to the well-known success of the African American professional prizefighter Jack Johnson, who had won the world heavyweight championship a year earlier.

The idea of a black boxing champion was so unsettling to the prejudiced social order of the time that many thought interracial bouts should be outlawed.

Painted at the height of the Jim Crow era, Bellows’s powerful image of a white fighter being pummeled by a black opponent was an exceptionally daring and provocative piece of social commentary.

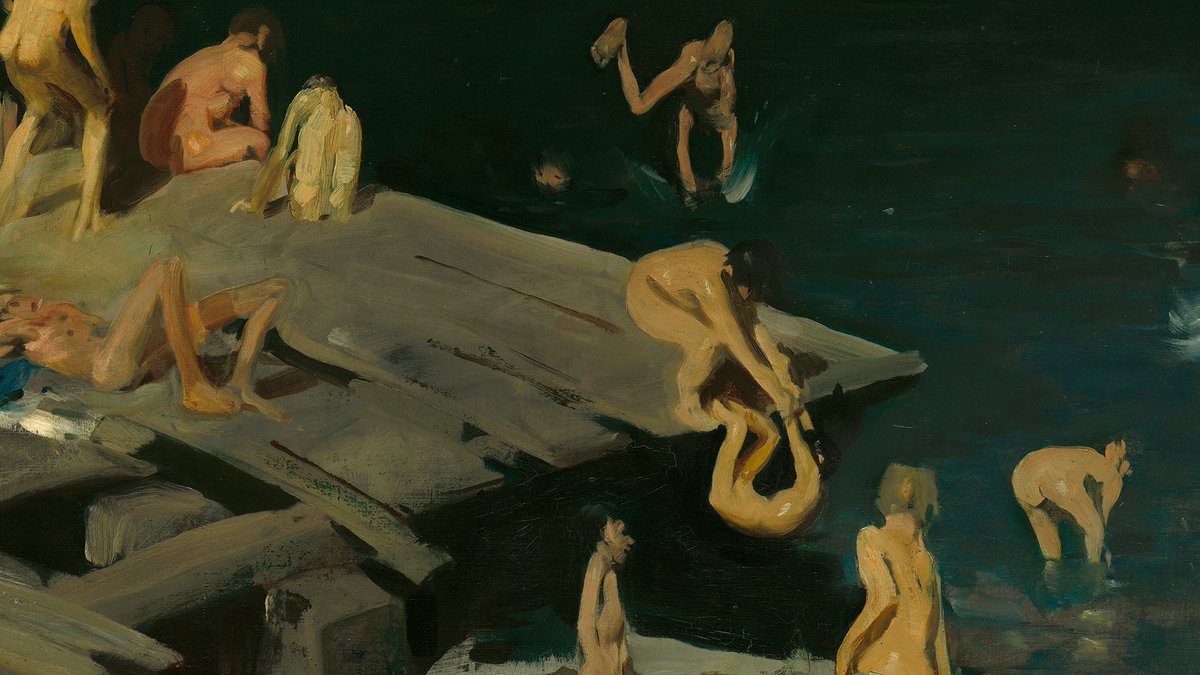

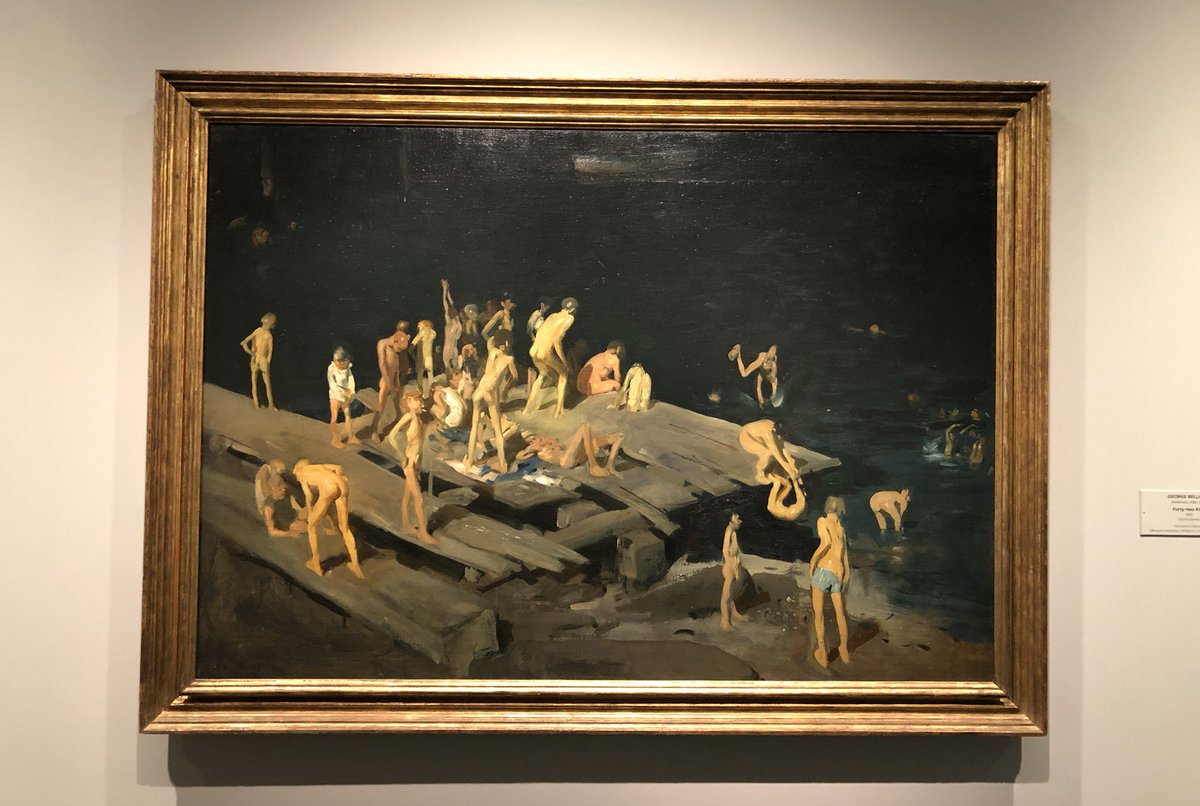

Bellows’s “Forty-two Kids” (1907) perfectly illustrates the artist’s adherence to his mentor Robert Henri’s credo of “art for life’s sake.”

Painted soon after he arrived in NYC from his native Ohio, the canvas depicts a band of nude and partially clothed boys engaged in a variety of antics—swimming, diving, sunbathing, smoking, and possibly urinating—on and near a dilapidated wharf jutting out over the East River.

In turn-of-the-century slang, "kids" referred to roaming young hooligans, who were frequently the children of working-class immigrants living in Lower East Side tenements.

["City children - bathing for free at the Battery, New York City" from the @LibraryofCongress]

["City children - bathing for free at the Battery, New York City" from the @LibraryofCongress]

The artist’s vigorous brushwork, conveying freshness and immediacy, is well suited to his outdoor urban subject.

The wharf is painted with broad, fluid strokes from a heavily laden paintbrush, and the figures are sketched with his characteristic economy of means.

The wharf is painted with broad, fluid strokes from a heavily laden paintbrush, and the figures are sketched with his characteristic economy of means.

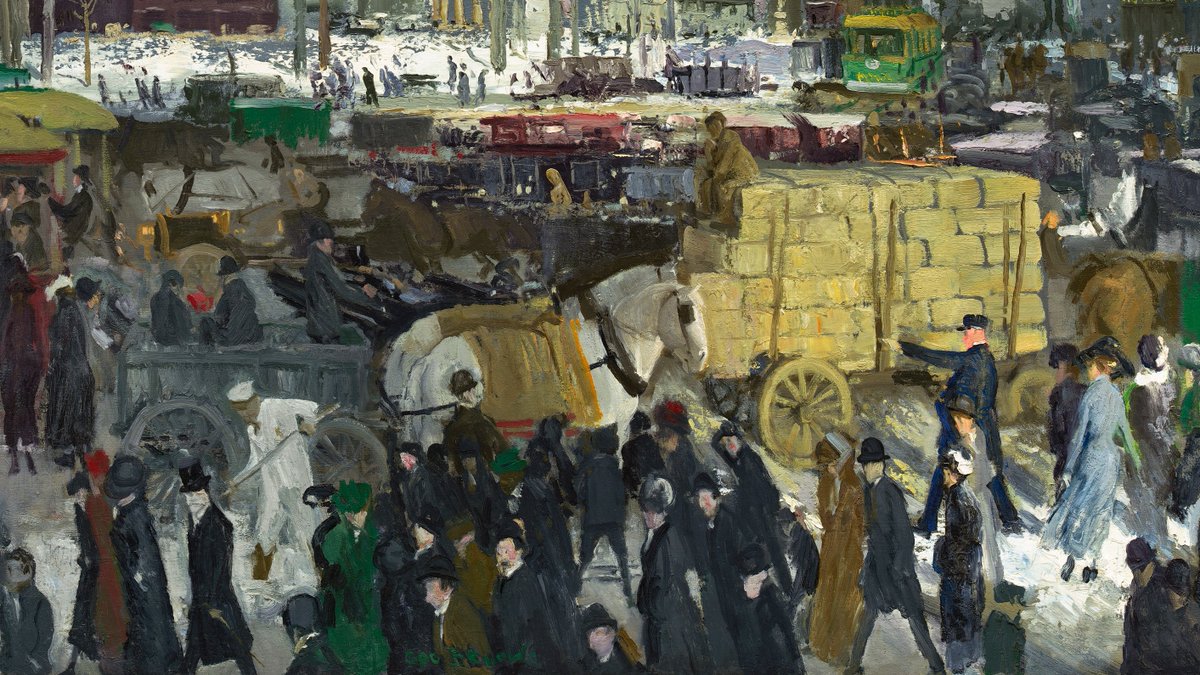

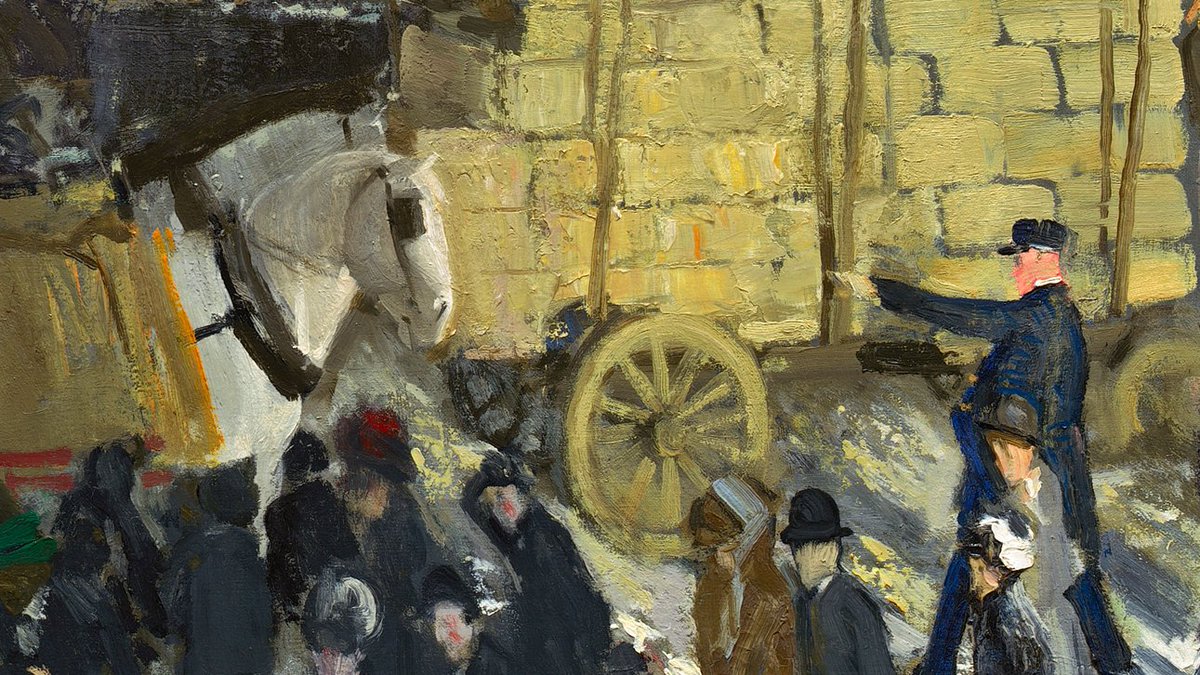

We turn next to Bellows’s “New York,” completed in 1911. This is a large, ambitious painting—the canvas is five feet wide—in which Bellows captures the New York City of his day.

Though the viewpoint is ostensibly the intersection of Broadway and 23rd Street looking uptown toward Madison Square, Bellows did not intend to represent a specific place in the city.

He instead drew on several bustling commercial districts to create an imaginary composite that would best convey the city’s frenetic pace.

In our current moment of social and physical distancing, the painting is a reminder of how the pandemic has changed our everyday lives.

Bellows would often include one figure who looks out of the painting, at the viewer. In “New York,” we find such a man at the bottom of the canvas, and his glance at us over his shoulder invites us into the scene.

In the middle of the crowd, there is a policeman trying in vain to direct both traffic and people. Horse-drawn carts pass him by, and pedestrians walk around him.

Among the skyscrapers, look for billboards that are nearly legible – but tantalizingly incomplete. Signage and lettering are everywhere, exemplifying the visual overload of the city.

In its portrayal of the frenetic pace and overstimulation of modern urban experience, this painting is as relevant today as it was in Bellows’s time.

We conclude the tour with two paintings by Edward Hopper, an artist whose works have been frequently referenced during this time of isolation and uncertainty.

These two paintings were made in 1939, one immediately after the other. The first is “Cape Cod, Evening.”

Hopper’s paintings have been compared to film stills, or moments of suspended narrative.

Hopper’s paintings have been compared to film stills, or moments of suspended narrative.

We encounter the two figures and the collie dog at an ambiguous moment. Their body language exudes tension, and the dog’s alert stance is foreboding. His gaze is directed at something we cannot see.

Hopper, usually evasive about his works’ interpretations, said, “The dog is listening to something, probably a whippoorwill or some evening sound.”

Adding to the sense of disquiet in the painting is the encroachment of the grove of blue-green locust trees upon the house. One tree is nearly touching the house, its branch outlined against the bay window.

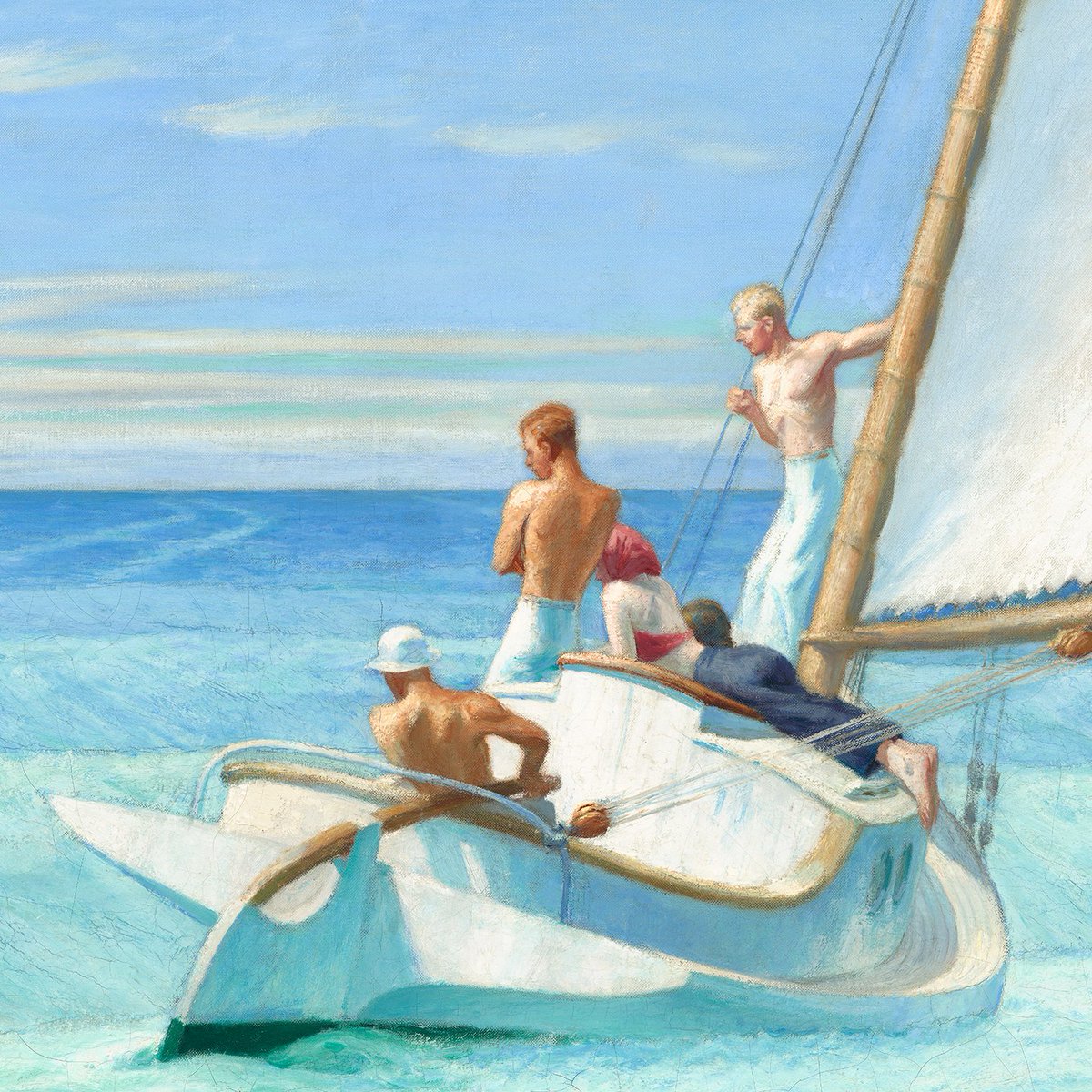

We can’t make out what lies beyond the forest, in the shadows. Hopper provides more questions than answers, both in this painting and in our final work, “Ground Swell.”

Despite its bright palette and seemingly serene subject, “Ground Swell” exemplifies the artist’s recurring themes of loneliness and escape.

The blue sky, sun-kissed figures, and vast rolling water strike a calm note in the picture. However, the disengagement of the figures from each other, and their preoccupation with the bell buoy placed at the center of the canvas, call into question this initial sense of serenity.

As Hopper was working on “Ground Swell,” in August and September of 1939, World War II broke out in Europe.

In 1940 Hopper mused about seeking solace during wartime in a passage that resonates today:

“Painting seems to be a good enough refuge from all this, if one can get one’s dispersed mind together long enough to concentrate upon it.”

“Painting seems to be a good enough refuge from all this, if one can get one’s dispersed mind together long enough to concentrate upon it.”

Thanks for following along on today’s tour of gallery 106C!

Learn more about this period of American painting in our “American Paintings, 1900–1945” Online Edition: http://go.usa.gov/xvWVr ">https://go.usa.gov/xvWVr&quo...

Learn more about this period of American painting in our “American Paintings, 1900–1945” Online Edition: http://go.usa.gov/xvWVr ">https://go.usa.gov/xvWVr&quo...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter

![But Henri was not interested in prescribing a specific style. He instead wanted his students to discover their own unique strategies for representing modern experience.“Do whatever you do intensely,” he said to his students.[John Sloan, detail of "Robert Henri, Painter, 1931] But Henri was not interested in prescribing a specific style. He instead wanted his students to discover their own unique strategies for representing modern experience.“Do whatever you do intensely,” he said to his students.[John Sloan, detail of "Robert Henri, Painter, 1931]](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/EVRWrI9XsDUytMU.jpg)

![Henri’s urban snowscape is fundamentally different from those by impressionist artists of the same period.[Camille Pissarro, “The Boulevard Montmartre on a Winter Morning,” 1897, @MetMuseum] Henri’s urban snowscape is fundamentally different from those by impressionist artists of the same period.[Camille Pissarro, “The Boulevard Montmartre on a Winter Morning,” 1897, @MetMuseum]](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/EVRXGh4WsAgATgC.jpg)

![Henri’s urban snowscape is fundamentally different from those by impressionist artists of the same period.[Camille Pissarro, “The Boulevard Montmartre on a Winter Morning,” 1897, @MetMuseum] Henri’s urban snowscape is fundamentally different from those by impressionist artists of the same period.[Camille Pissarro, “The Boulevard Montmartre on a Winter Morning,” 1897, @MetMuseum]](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/EVRXH2hXYAAEiuJ.jpg)

![As a portrait painter, Henri remained true to his belief in “art for life’s sake,” depicting sitters from varying backgrounds. [“Catharine,” 1913] As a portrait painter, Henri remained true to his belief in “art for life’s sake,” depicting sitters from varying backgrounds. [“Catharine,” 1913]](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/EVRYNH_WkAUQVzR.jpg)

![John Sloan, along with fellow newspaper illustrators William Glackens, George Luks, and Everett Shinn, was encouraged by Henri to move from Philadelphia to New York around the turn of the century and become painters.[Photo of Shinn, Henri, and Sloan from the @ArchivesAmerArt] John Sloan, along with fellow newspaper illustrators William Glackens, George Luks, and Everett Shinn, was encouraged by Henri to move from Philadelphia to New York around the turn of the century and become painters.[Photo of Shinn, Henri, and Sloan from the @ArchivesAmerArt]](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/EVRZ2gtWkAI6Cjh.jpg)

![In turn-of-the-century slang, "kids" referred to roaming young hooligans, who were frequently the children of working-class immigrants living in Lower East Side tenements.["City children - bathing for free at the Battery, New York City" from the @LibraryofCongress] In turn-of-the-century slang, "kids" referred to roaming young hooligans, who were frequently the children of working-class immigrants living in Lower East Side tenements.["City children - bathing for free at the Battery, New York City" from the @LibraryofCongress]](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/EVRhXi8X0AEF_tc.jpg)

![In turn-of-the-century slang, "kids" referred to roaming young hooligans, who were frequently the children of working-class immigrants living in Lower East Side tenements.["City children - bathing for free at the Battery, New York City" from the @LibraryofCongress] In turn-of-the-century slang, "kids" referred to roaming young hooligans, who were frequently the children of working-class immigrants living in Lower East Side tenements.["City children - bathing for free at the Battery, New York City" from the @LibraryofCongress]](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/EVRhXzkWAAArd68.jpg)