Farm to table, the US has the most productive food supply chain in the world.

However, as consumers& #39; relationship to the source of their food have shifted, it has driven an increase in misinformation and fear.

Let& #39;s plant some knowledge.

Thread.

First, the most salient fact of all: the US produces more than 4,000 cal worth of food per person, per day.

However, the USDA estimates (as of 2010) that 37.5% (1,500 cal) of that production goes to waste.

Clearly, US farmers and importers have made food abundant.

2/

However, the USDA estimates (as of 2010) that 37.5% (1,500 cal) of that production goes to waste.

Clearly, US farmers and importers have made food abundant.

2/

What the US fundamentally faces then is not raw supply of (potential) food products.

There are three issues that contribute to food fear in the US:

1. Consumption habits

2. Distribution of demand for US ag products

3. Transportation/infrastructure

3/

There are three issues that contribute to food fear in the US:

1. Consumption habits

2. Distribution of demand for US ag products

3. Transportation/infrastructure

3/

Now when I say US farmers and ranchers are wildly productive, I mean it.

The US leads the world in agriculture innovation - from more efficient equipment to precision agronomy to scientific breakthroughs, the average farm in the US skews more high-tech each year.

4/

The US leads the world in agriculture innovation - from more efficient equipment to precision agronomy to scientific breakthroughs, the average farm in the US skews more high-tech each year.

4/

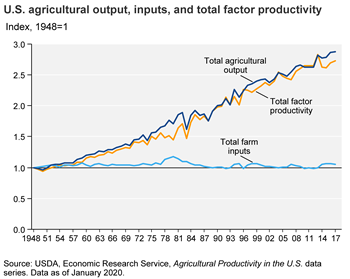

Consider this chart: based on the relative amount of inputs per acre (seed, chem, fertilizer, fuel, land, and labor), the US has remained static since 1948.

But thanks to better practices, equipment, and technology, output has tripled.

This is a marvel of human ingenuity.

5/

But thanks to better practices, equipment, and technology, output has tripled.

This is a marvel of human ingenuity.

5/

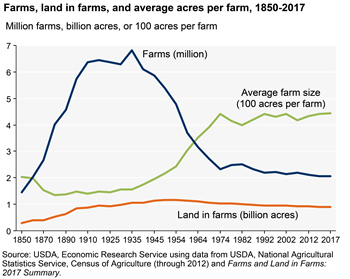

However, fewer families are farming than ever.

US farms peaked in 1935 at 6.8 million against a total US pop of 127.3 million. A huge percentage of the US was involved in ag in some way.

By 2017, there were only 2.05 million farms to feed 325.7 million people.

6/

US farms peaked in 1935 at 6.8 million against a total US pop of 127.3 million. A huge percentage of the US was involved in ag in some way.

By 2017, there were only 2.05 million farms to feed 325.7 million people.

6/

In short, the US is producing more food than ever, with fewer growers than ever.

The type of grower has shifted as well.

Farming is still a family business, overall. But thanks to macroeconomic factors, the trend is towards much larger, corporate-style farms.

7/

The type of grower has shifted as well.

Farming is still a family business, overall. But thanks to macroeconomic factors, the trend is towards much larger, corporate-style farms.

7/

The "whys" of this trend are hotly-disputed in the ag community.

Having spent some years at the nexus of the debate (even being called a few names on http://AgTalk.com"> http://AgTalk.com for working with mega-farms), I can say that there is no one or two single issues.

It& #39;s many.

8/

Having spent some years at the nexus of the debate (even being called a few names on http://AgTalk.com"> http://AgTalk.com for working with mega-farms), I can say that there is no one or two single issues.

It& #39;s many.

8/

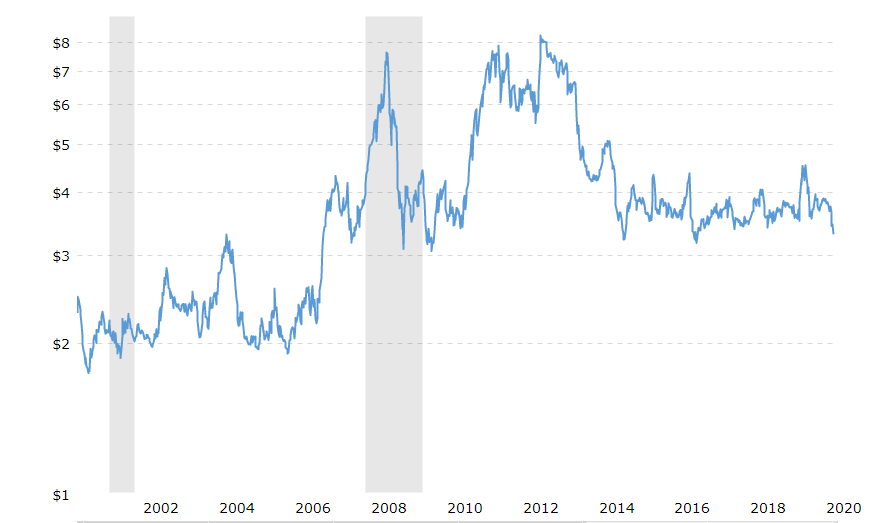

And at this point, the trends are likely irreversible.

When corn prices decoupled from reality in 2006 thanks to an explosion in demand for ethanol, it started an upswing in market, input, and land prices.

Everything got more expensive, even as crop prices came back down.

9/

When corn prices decoupled from reality in 2006 thanks to an explosion in demand for ethanol, it started an upswing in market, input, and land prices.

Everything got more expensive, even as crop prices came back down.

9/

Likewise, the US enjoyed a strong uptick in exports of not just the crops themselves, but co-products of refining such as DDGS and soybean meal (SBM).

These became cheap, high-demand protein sources for Asia to feed their growing poultry flocks and herds of swine/beef.

10/

These became cheap, high-demand protein sources for Asia to feed their growing poultry flocks and herds of swine/beef.

10/

China in particular became the demand bull, especially from 2010-2014.

But as I& #39;ve written about before, that golden age was the calm before the storm.

At the end of 2013, China declared asymmetric war on their own food insecurity.

11/ https://twitter.com/man_integrated/status/1195050562728943619">https://twitter.com/man_integ...

But as I& #39;ve written about before, that golden age was the calm before the storm.

At the end of 2013, China declared asymmetric war on their own food insecurity.

11/ https://twitter.com/man_integrated/status/1195050562728943619">https://twitter.com/man_integ...

Separate from the US staple crops of grains/soy, the news is no better for the livestock, produce, and dairy sectors.

The major distinction is that the primary markets for corn/soy are processors who convert them into food ingredients, biofuel, or animal feed.

12/

The major distinction is that the primary markets for corn/soy are processors who convert them into food ingredients, biofuel, or animal feed.

12/

The supply chains for these are fairly static. Grains/soy tend to move in bulk once or twice, then be turned into a new product. Demand is also less elastic.

X qty to become animal feed.

X qty to become food ingredients.

X qty to become biofuels.

They are less unstable.

13/

X qty to become animal feed.

X qty to become food ingredients.

X qty to become biofuels.

They are less unstable.

13/

The other products are more sensitive to demand disruptions (such as economic slowdown or COVID-19) because they are much closer to the consumer& #39;s table.

Meat is butchered and sold. Dairy is processed once, then sold. Produce is processed not at all, or once, then sold.

14/

Meat is butchered and sold. Dairy is processed once, then sold. Produce is processed not at all, or once, then sold.

14/

Whereas grains/soy are processed into thousands of products (starches, sweeteners, additives, protein, vegan), livestock, dairy, fruits, nuts, and veggies more or less begin and end as the same thing.

There& #39;s few intermediate markets to absorb price shock or demand decline.

15/

There& #39;s few intermediate markets to absorb price shock or demand decline.

15/

Thus, US consumer behavior is closely tied to these more-sensitive food items.

So too are the supply chains to move these products from farm to table more specialized.

Produce must be segregated by quality. Liquids move in expensive tankers. Meat must stay cold.

16/

So too are the supply chains to move these products from farm to table more specialized.

Produce must be segregated by quality. Liquids move in expensive tankers. Meat must stay cold.

16/

Grain or soybeans can be put into a barge, sailed downriver for two weeks, load to a ship, then end up in Asia another month later with little spoilage.

But these other products must be "turned" as fast as possible through direct sales, reprocessing, or freezing.

17/

But these other products must be "turned" as fast as possible through direct sales, reprocessing, or freezing.

17/

If restaurants and schools have reduced consumption, they& #39;re buying less from suppliers, who buy less at the farm level.

Hence the stories we& #39;re now seeing about massive spoilage on-farm.

The risk has been transferred from the end of the supply chain to the front of it.

18/

Hence the stories we& #39;re now seeing about massive spoilage on-farm.

The risk has been transferred from the end of the supply chain to the front of it.

18/

So when we see stories about food insecurity in the US arising from COVID-19, what we& #39;re seeing is a demand disruption for perishable goods.

It& #39;s very important to note that more people aren& #39;t starving to death specifically due to this supply chain disruption.

19/

It& #39;s very important to note that more people aren& #39;t starving to death specifically due to this supply chain disruption.

19/

Another disruption is that of transport capacity, especially for perishable items.

Refrigerated trucks ("reefers") carry much of the dry/packaged goods, and specialty tankers carry bulk liquids like milk.

Change in demand increases prices and disclocates assets.

20/

Refrigerated trucks ("reefers") carry much of the dry/packaged goods, and specialty tankers carry bulk liquids like milk.

Change in demand increases prices and disclocates assets.

20/

The more specialized the transport, the less capacity can "flex".

A regular dry van trailer can move nearly any cargo.

A tanker can only move a few products. The assets depend on reliable volumes. Carriers who can& #39;t make money will change trailers and carry something else.

21/

A regular dry van trailer can move nearly any cargo.

A tanker can only move a few products. The assets depend on reliable volumes. Carriers who can& #39;t make money will change trailers and carry something else.

21/

Lastly, an issue affecting meat is the stoppage of in-person livestock auctions, where a good portion of business occurs in that sector.

Reduction in meat packing capacity is also an issue.

However, these are temporary issues - unless the economy stays shut down.

22/

Reduction in meat packing capacity is also an issue.

However, these are temporary issues - unless the economy stays shut down.

22/

For people newly facing food insecurity, it& #39;s more a result of less money to buy food because of reduced (or eliminated) income.

For farmers it& #39;s an emergent revenue crisis that is doubly galling after seeing $6 trillion go to a variety of political interests.

23/

For farmers it& #39;s an emergent revenue crisis that is doubly galling after seeing $6 trillion go to a variety of political interests.

23/

The upshot is that farms are hardest-hit right now, even as shelves remain mostly full. A continued slowdown during planting season will have a durable impact for the rest of the year, even if the economy recovers somewhat.

We need to address this potential crisis.

24/

We need to address this potential crisis.

24/

First, farmers are beginning their spring crop cycle in the greatest economic uncertainty most have ever faced.

The USDA needs to take all measures to financially protect producers for the & #39;20-21 marketing cycle, especially w/ robust direct payments at the farm level.

25/

The USDA needs to take all measures to financially protect producers for the & #39;20-21 marketing cycle, especially w/ robust direct payments at the farm level.

25/

Second, waive all hours of service and weight limit restrictions for drivers carrying food or food-adjacent goods (packaging, for example).

Third, price caps on inputs and taxes.

Fourth, subsidies for freight payors moving food products.

26/

Third, price caps on inputs and taxes.

Fourth, subsidies for freight payors moving food products.

26/

Fifth, renegotiation of loans and restructuring of debt to reduce cash flow burden and extend repayment terms.

Sixth, institute national food stockpile program under the guidance of a National Quartermaster.

27/

Sixth, institute national food stockpile program under the guidance of a National Quartermaster.

27/

Seventh, offer a "Mongomery GI Bill" for young adults staying on farm, w/ emphasis on high-tech skills training, income support, and use of farm as innovation clusters for new best practices, cropping techniques, and animal management.

Eighth, rural hi-speed internet. NOW.

28/

Eighth, rural hi-speed internet. NOW.

28/

Ninth, replace missing migrant workers on-farm with paid prison laborers - qualified by good behavior and nature of offense.

Tenth, summer work programs for teenagers and college students at local farms, subsidized by colleges, schools, and extension programs.

29/

Tenth, summer work programs for teenagers and college students at local farms, subsidized by colleges, schools, and extension programs.

29/

I& #39;m not presently interested in a debate about GMO& #39;s, ecological impact, luxury diets, etc.

We& #39;ll fight those battles later.

We have a system in place, and letting it burn down will cause more misery than it solves.

Serious changes do need to be made, at the right time.

30/

We& #39;ll fight those battles later.

We have a system in place, and letting it burn down will cause more misery than it solves.

Serious changes do need to be made, at the right time.

30/

These recommendations are a mix of right-now and long term proposals.

The fact is that whatever happens with COVID-19, the most essential link in our food supply chain is already being crushed, especially after years of struggle.

Our future depends on saving our farms.

31/

The fact is that whatever happens with COVID-19, the most essential link in our food supply chain is already being crushed, especially after years of struggle.

Our future depends on saving our farms.

31/

Addendum:

This song came out in 1985 during one of the worst financial crises ever endured by American farms.

It& #39;s as timely now as it was then. https://youtu.be/joNzRzZhR2Y ">https://youtu.be/joNzRzZhR...

This song came out in 1985 during one of the worst financial crises ever endured by American farms.

It& #39;s as timely now as it was then. https://youtu.be/joNzRzZhR2Y ">https://youtu.be/joNzRzZhR...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter