Spices, Easter cooking, early medieval world. How important it was to spice up your meal in the 8th century (if you could afford it) and what does it tell us about the relationship of Western Europe with spices? Plus spices as a medieval fad. A thread. #Medieval #Foodie 1/

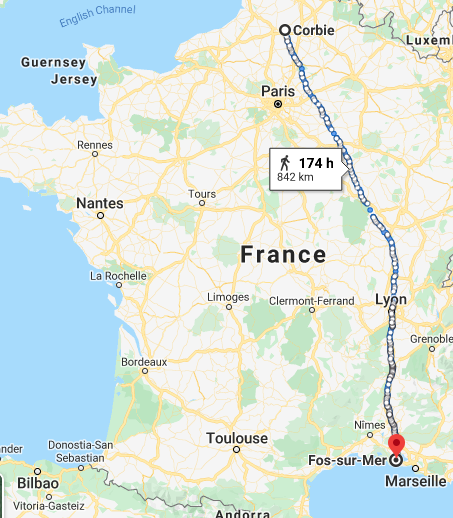

We start here, in Corbie, Northern France. In 716 a Merovingian king Chilperic II (they had the best names) confirmed the privileges granted by Chlothar III (652–73) to the abbey. They included an exemption on tax on certain goods in the royal toll station on the Rhone in Fos 2/

Now it& #39;s a bit of a ride from Fos to Corbie so the privilege stipulates also a whole set of provisions for the transport of the said goods. Carts, escort and so on. You don& #39;t want to take any chances. 3/

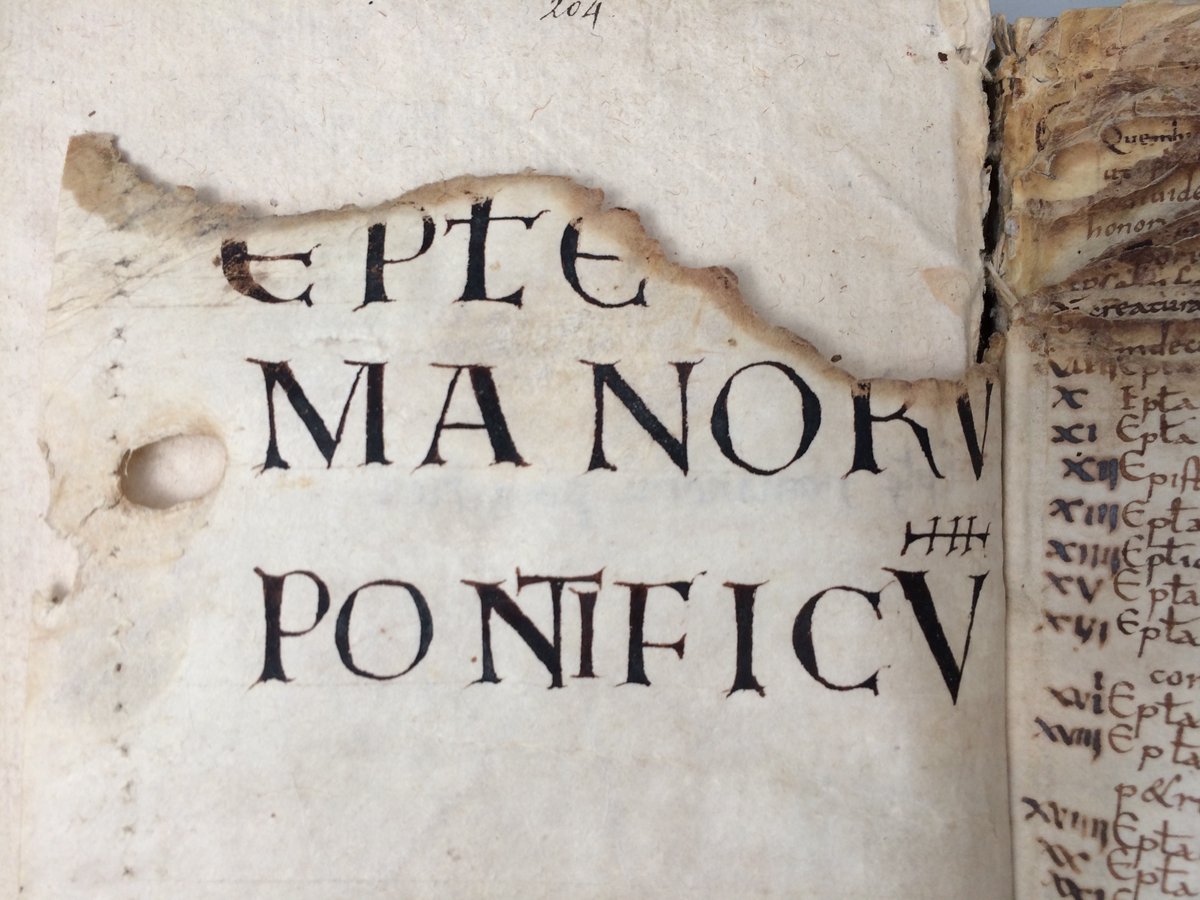

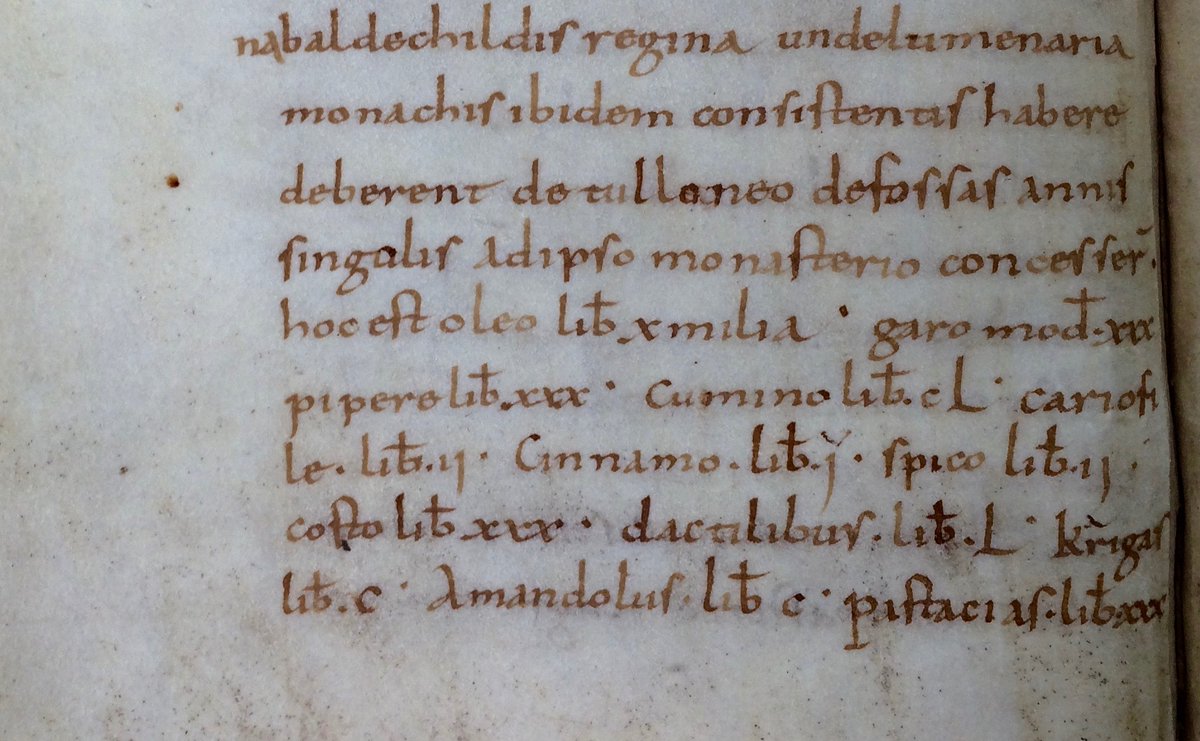

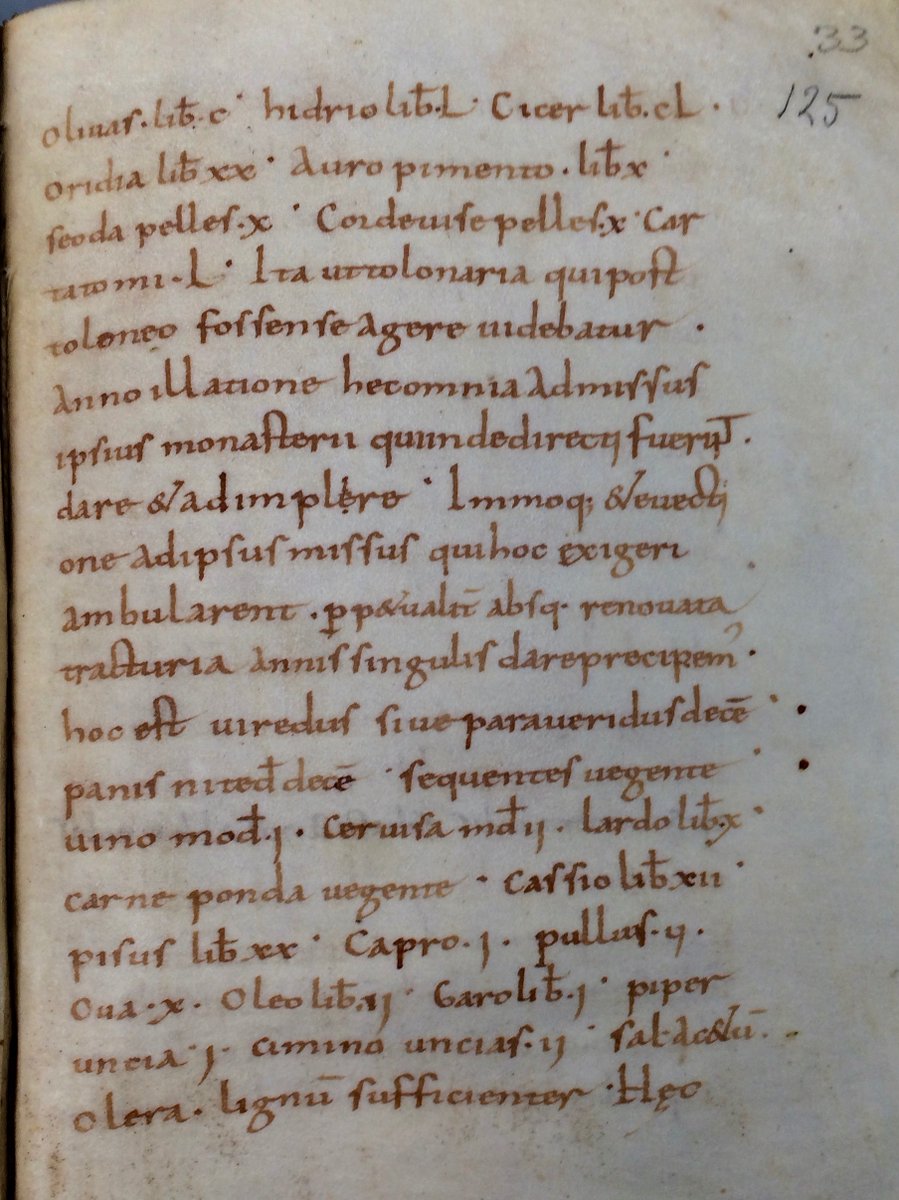

The list of those goods is very interesting. And we have it thanks to a copy of this charter preserved in a 9th century manuscript made in Corbie (Berlin Phill 1776). This ms is, nerd alert, awesome. It contains letters of the popes (which makes it an important book!) 4/

At the end of it four privileges are preserved, including the one by Chiliperic II. It& #39;s mostly tax exemptions (booooring), but among those we get a list of materials that the abbey of Corbie had the right to import, toll-free. And boy is it cool. 5/

The quantities are on the massive side.

10 000 pounds of oil

30 drums of garum (think fish sauce but gross)

30 pounds of pepper

150 pounds of cumin

2 pounds of cloves

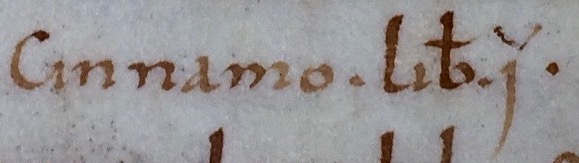

1 pound of cinnamon (dutifully corrected to: 5!)

plus various amounts of almonds, pistachios and dates 6/

10 000 pounds of oil

30 drums of garum (think fish sauce but gross)

30 pounds of pepper

150 pounds of cumin

2 pounds of cloves

1 pound of cinnamon (dutifully corrected to: 5!)

plus various amounts of almonds, pistachios and dates 6/

The list goes on: there is rice (20 pounds), chickpeas (150 pounds) and Cordova leather. And: 50 sheets of papyrus ("carta tomi L")! 7/

Now this is not a small amount of spices and nuts. Some of it, like cloves, as @siwaratrikalpa can tell you in way more detail, would come (through many intermediaries) all the way from Indonesia. There are a lot of questions though. 8/

Some scholars have pointed out (Loseby 1992)¹ that this is just a wish list in 716. That yes, it does represent vivid trade in eastern commodities through the port of Marseille but in the 7th century and not the 8th. 9/

¹ There will be a bibliography at the end, bear with me.

¹ There will be a bibliography at the end, bear with me.

But you see we know that spices were a bit of an early medieval fad, a Thingᵗᵐ that the cool people would use. They were seen as fashionable remedies (just like your turmeric latte nowadays) but also used in cooking! 10/

In fact we know from Cuthbert& #39;s letter describing the death of Bede that among his most treasured possessions was a box containing some pepper. And Bede died in 735.

BL Yates Thompson MS 26 (probably not Bede, but long assumed to be Bede) 11/

BL Yates Thompson MS 26 (probably not Bede, but long assumed to be Bede) 11/

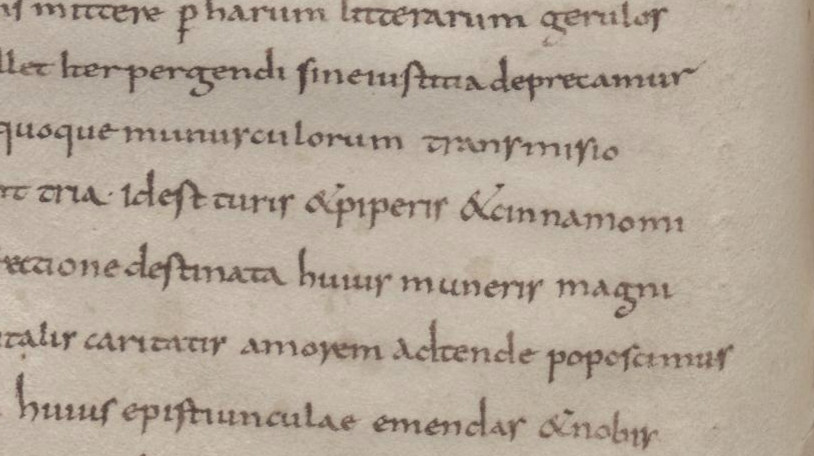

Now let us say you are writing a letter to your mentoress. You are with St Boniface on the Continent busily evangelising and it& #39;s 730s. You need to send gifts! What do you send? Well, frankincense, pepper, and cinnamon of course!

Wien, ÖNB, Cod. 751, 9th century 12/

Wien, ÖNB, Cod. 751, 9th century 12/

This is from a letter by Denehard, Lul, and Burchard to abbess Cuneburg, a very powerful figure in 8th century Wessex. They write from the area of today& #39;s Germany and really want to flatter her so obvs, just the best stuff can be sent. 13/

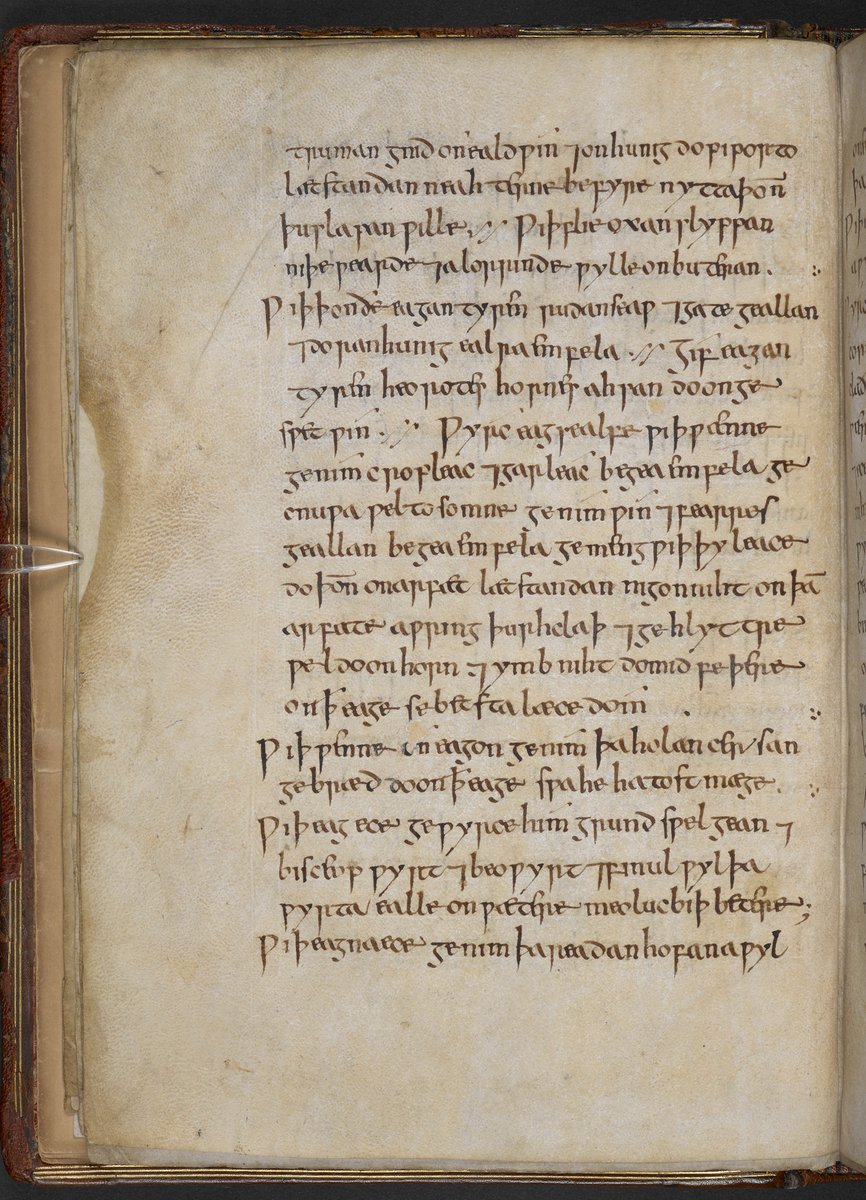

Ok, so we know that spices were present in Western Europe at the time when the grant was renewed. Bald& #39;s Leechbook (a collection remedies from EM England) mentions pepper, ginger, and cumin among the ingredients. 14/

BL Royal MS 12 D XVII

BL Royal MS 12 D XVII

We also know ( @HistorianofArch 2019) that other monasteries received similar grants allowing them to at least entertain the most important guest with finely spiced meals. 15/

For the scribe who copied the grant into Phill. 1776 clearly being correct in the amounts that the monastery could receive was important: here the amount of cinnamon was corrected from 1 to 5 pounds.² 16/

² Palaeography saves lives.

² Palaeography saves lives.

So yes, it is very much probable that the toll station in Fos did not process those exact quantities of spices in 716. But clearly *some* were still available. And we know from other sources that spices like pepper, cumin and cinnamon, although luxurious, were present. 17/

Yes, they were only available to a certain segment of the society and yes, there was a marked decline in imports after the end of the 7th century (Loseby 2000), and the amounts were small by today& #39;s standards, but they were a fixture in early medieval Europe. 18/

The next time you put a little cumin in your sauce or bake a cinnamon bun (pictured) remember that those spices and the people and the exchanges that brought us those spices are with us for a long time! 19/

A Very Short Bibliography

Sources:

Chilperic& #39;s privilege #page/424/mode/1up">https://www.dmgh.de/mgh_dd_merov_1/index.htm #page/424/mode/1up

Letter">https://www.dmgh.de/mgh_dd_me... from Denehard, Lul, and Burchard https://epistolae.ctl.columbia.edu/letter/351.html

Bald& #39;s">https://epistolae.ctl.columbia.edu/letter/35... Leechbook (old edition, not the best translation) https://archive.org/details/leechdomswortcun02cock">https://archive.org/details/l...

Sources:

Chilperic& #39;s privilege #page/424/mode/1up">https://www.dmgh.de/mgh_dd_merov_1/index.htm #page/424/mode/1up

Letter">https://www.dmgh.de/mgh_dd_me... from Denehard, Lul, and Burchard https://epistolae.ctl.columbia.edu/letter/351.html

Bald& #39;s">https://epistolae.ctl.columbia.edu/letter/35... Leechbook (old edition, not the best translation) https://archive.org/details/leechdomswortcun02cock">https://archive.org/details/l...

Literature (there is a lot on the subject, this is just a glimpse):

Effros (2019) https://books.google.de/books?id=782kDwAAQBAJ&dq

Latouche">https://books.google.de/books... (2013) https://books.google.de/books?id=vR38AQAAQBAJ&dq

Loseby">https://books.google.de/books... (1992) https://www.jstor.org/stable/301290

Loseby">https://www.jstor.org/stable/30... (2000) #v=onepage&q&f=false">https://books.google.de/books?id=F6FbuKU3ZAYC&printsec=frontcover #v=onepage&q&f=false

Pirenne">https://books.google.de/books... (1937) https://books.google.de/books?id=zLGeWH7WPmUC&dq">https://books.google.de/books...

Effros (2019) https://books.google.de/books?id=782kDwAAQBAJ&dq

Latouche">https://books.google.de/books... (2013) https://books.google.de/books?id=vR38AQAAQBAJ&dq

Loseby">https://books.google.de/books... (1992) https://www.jstor.org/stable/301290

Loseby">https://www.jstor.org/stable/30... (2000) #v=onepage&q&f=false">https://books.google.de/books?id=F6FbuKU3ZAYC&printsec=frontcover #v=onepage&q&f=false

Pirenne">https://books.google.de/books... (1937) https://books.google.de/books?id=zLGeWH7WPmUC&dq">https://books.google.de/books...

P.S. Some excellent literature additions from @monicaMedHist:

https://twitter.com/monicamedhist/status/1248870097260646402?s=21">https://twitter.com/monicamed... https://twitter.com/monicaMedHist/status/1248870097260646402">https://twitter.com/monicaMed...

https://twitter.com/monicamedhist/status/1248870097260646402?s=21">https://twitter.com/monicamed... https://twitter.com/monicaMedHist/status/1248870097260646402">https://twitter.com/monicaMed...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter