I took a look back through the @WinnipegNews archives to see what life was like in Winnipeg during the 1918 Spanish Flu Pandemic. So much of it is strikingly familiar and could be lifted off those old pages and reprinted today.

– a very long thread (I know you have time) 1/50

– a very long thread (I know you have time) 1/50

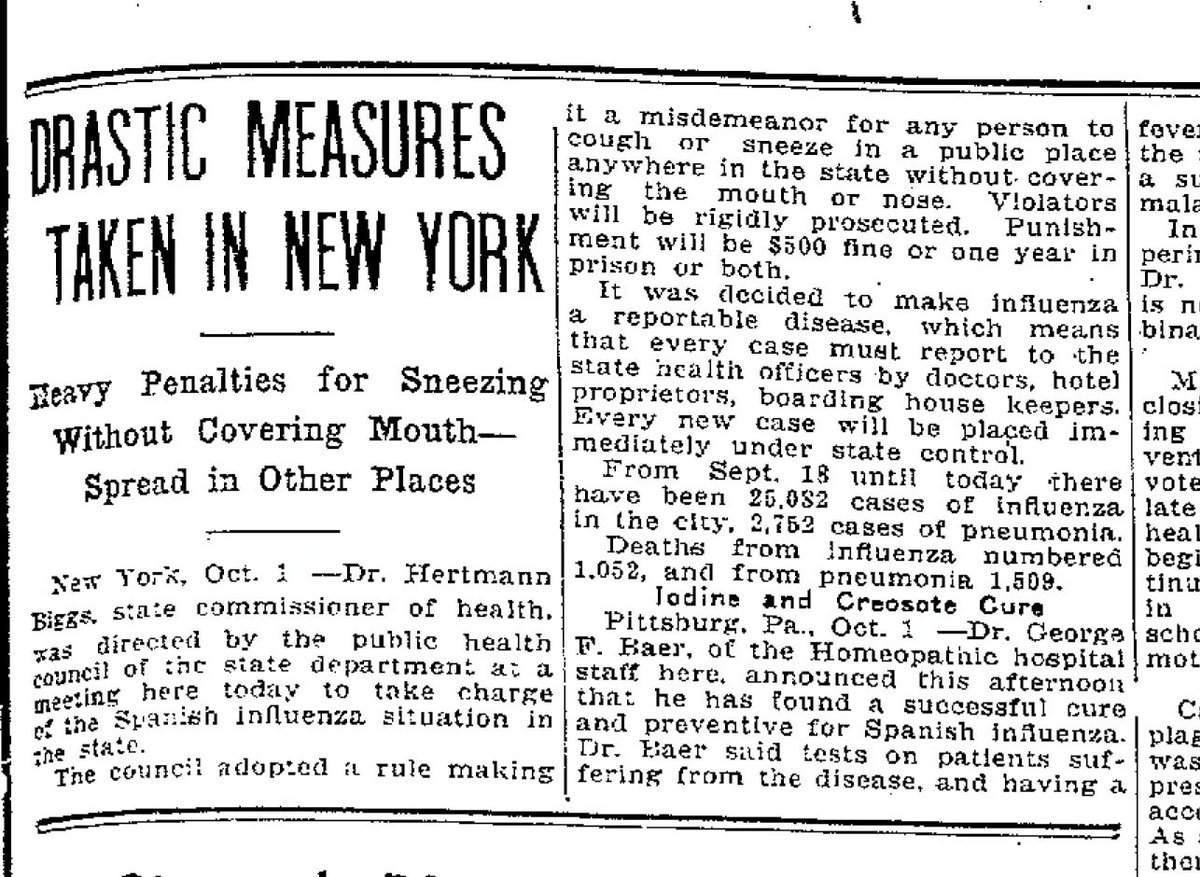

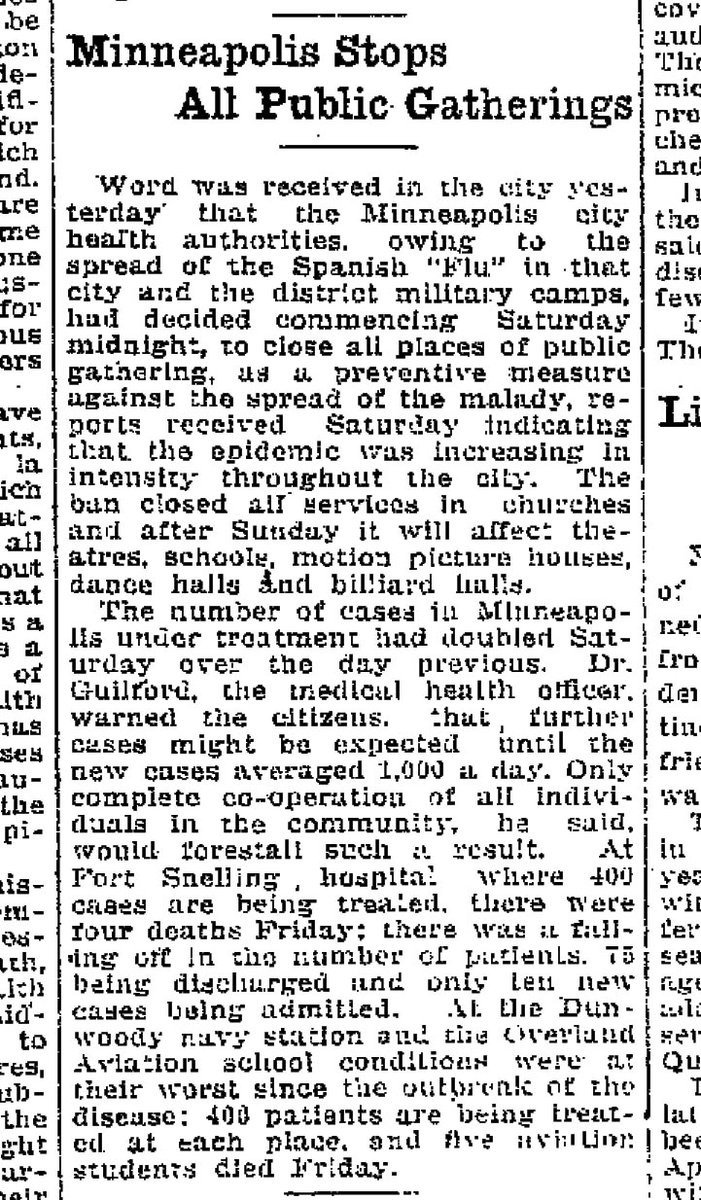

At first the local news was watching in disbelief as headlines from other places showed a devastating pandemic sweeping across the world. First on another continent and then to the eastern United States. Like today, New York was a hot spot reporting 25,000 cases in a few weeks.

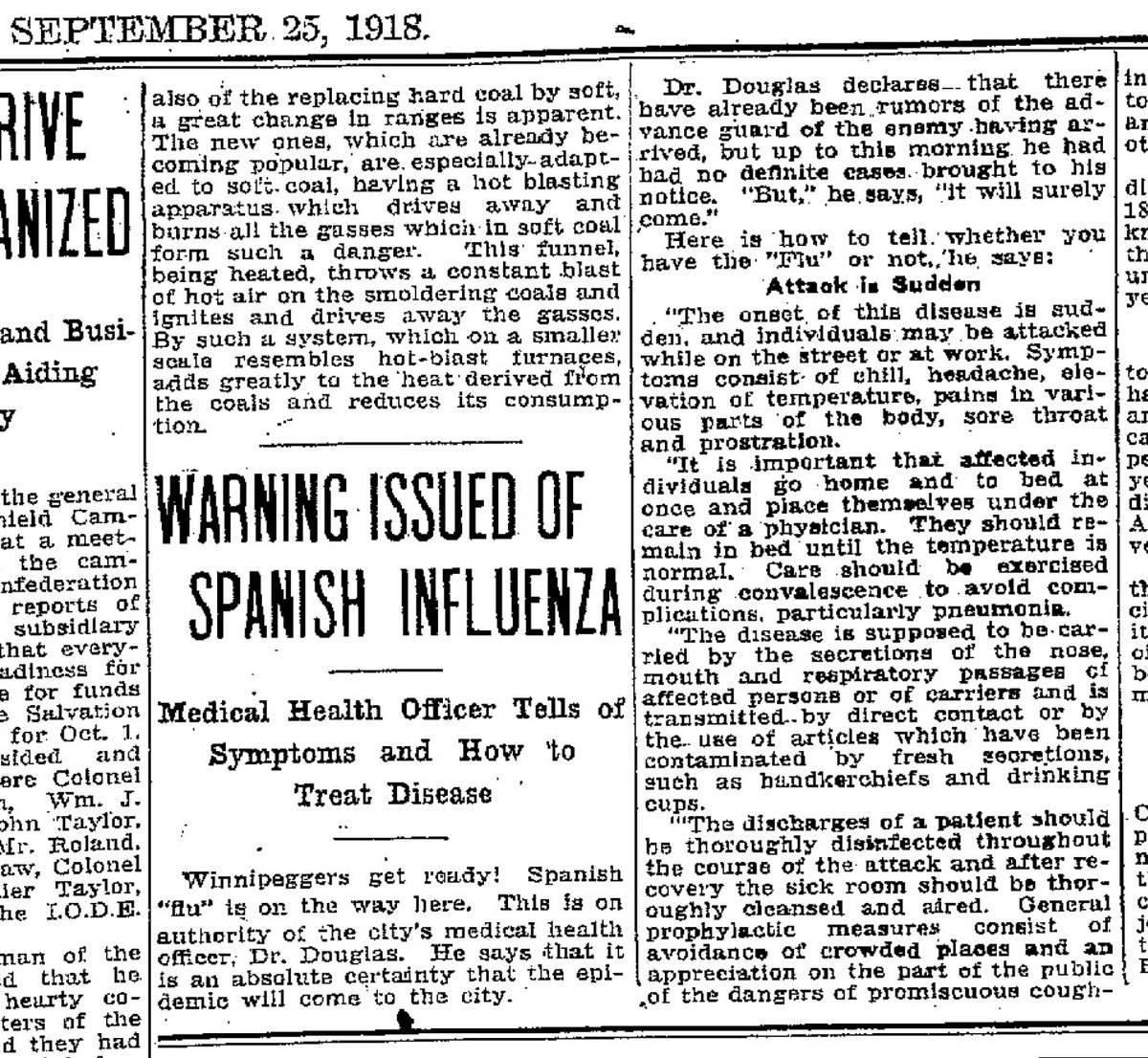

‘Winnipeggers get ready!’ - By the last week of September 1918, a statement was issued by the medical health officer, warning that the pandemic was coming and explaining what could be expected.

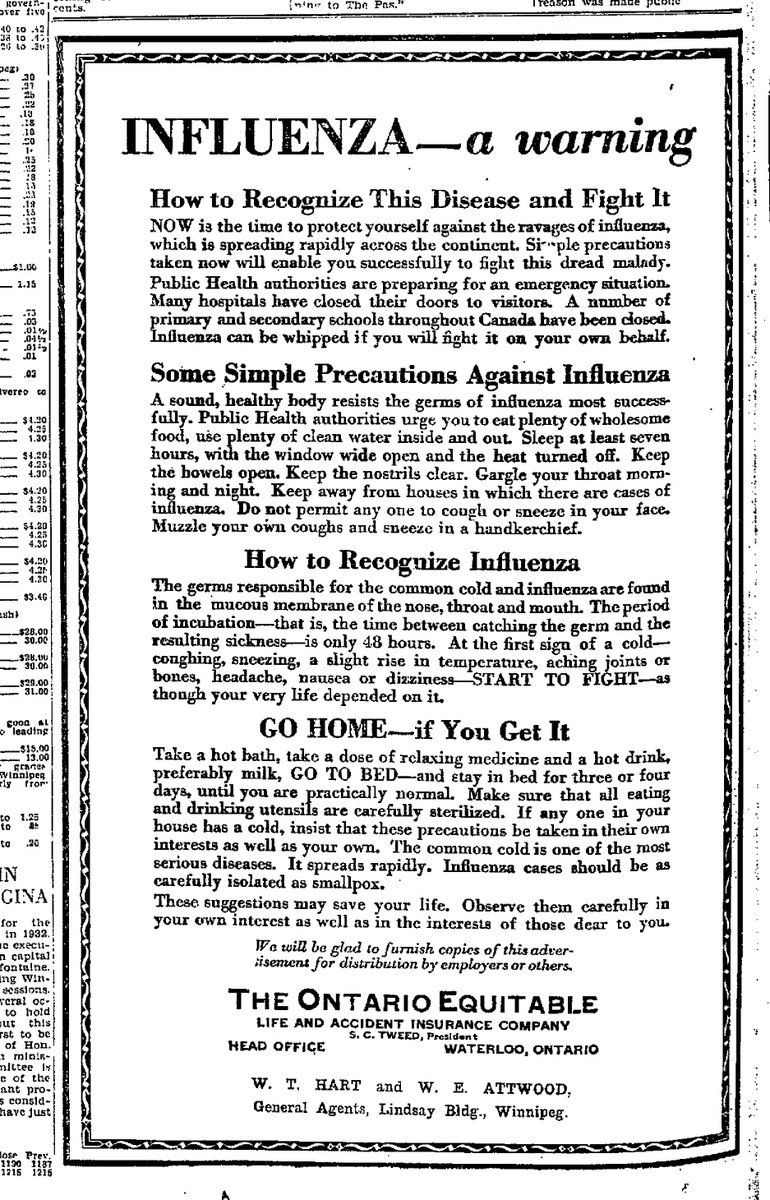

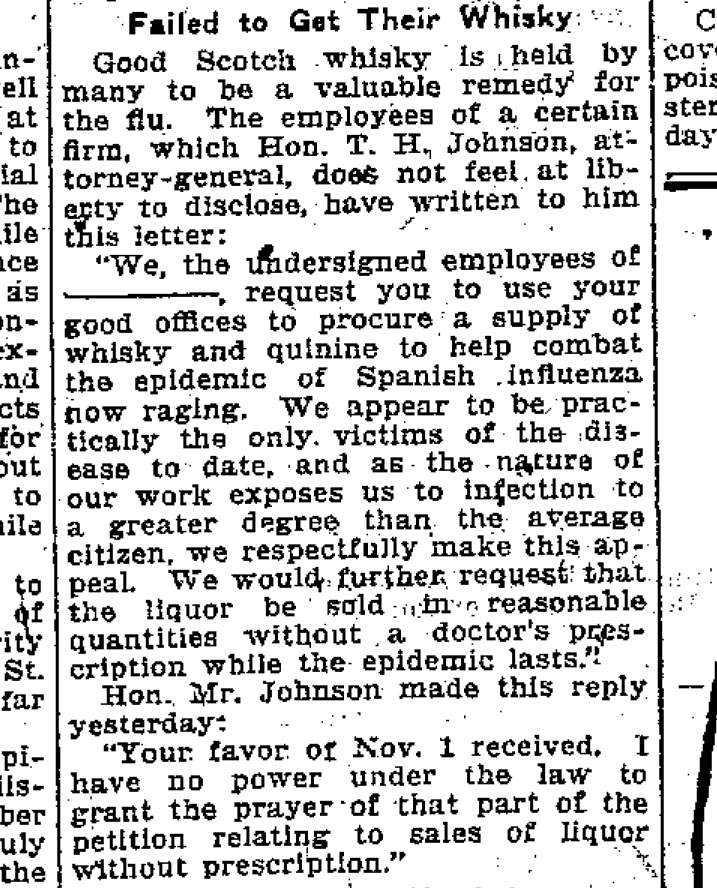

By early October a few cases began to appear in Winnipeg, without major headlines. The newspaper was filled with advertisements for various remedies in preparation. Whiskey was widely debated as a treatment.

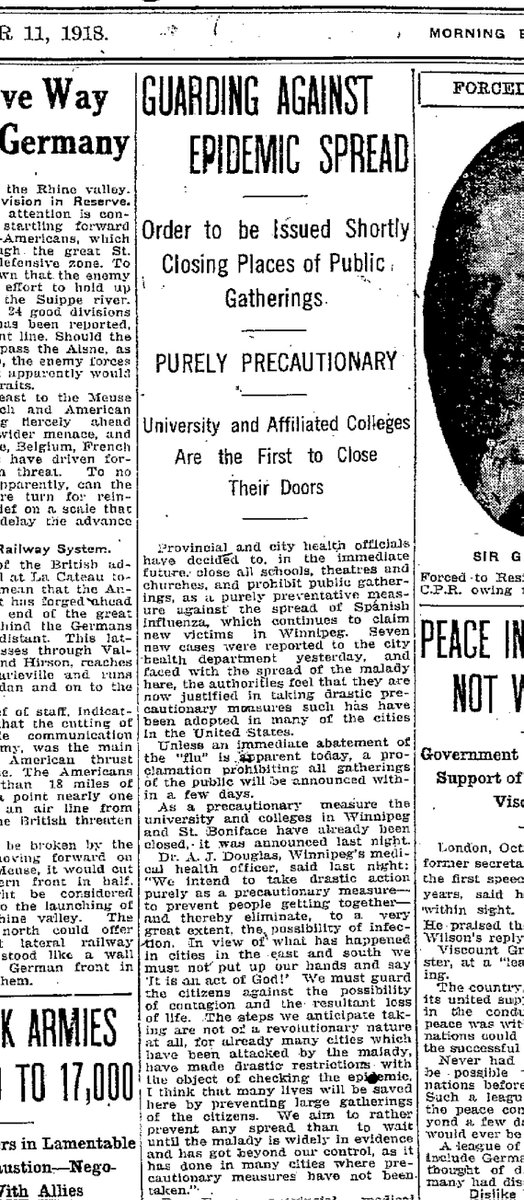

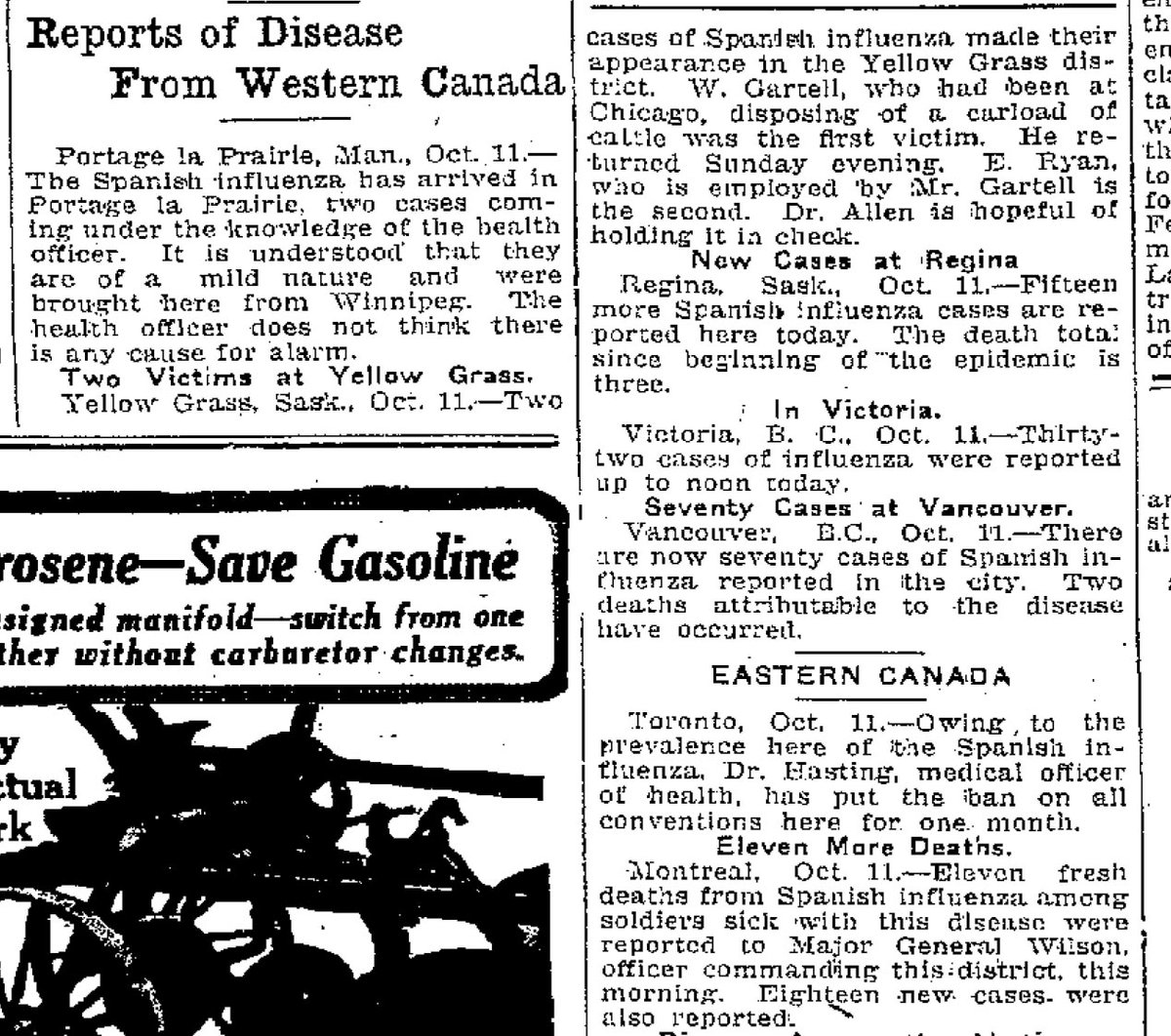

Similar to today, the virus arrived in Manitoba later than in most places, so with only a few confirmed cases, the city moved quickly. On October 11 the front page warned of impending closures.

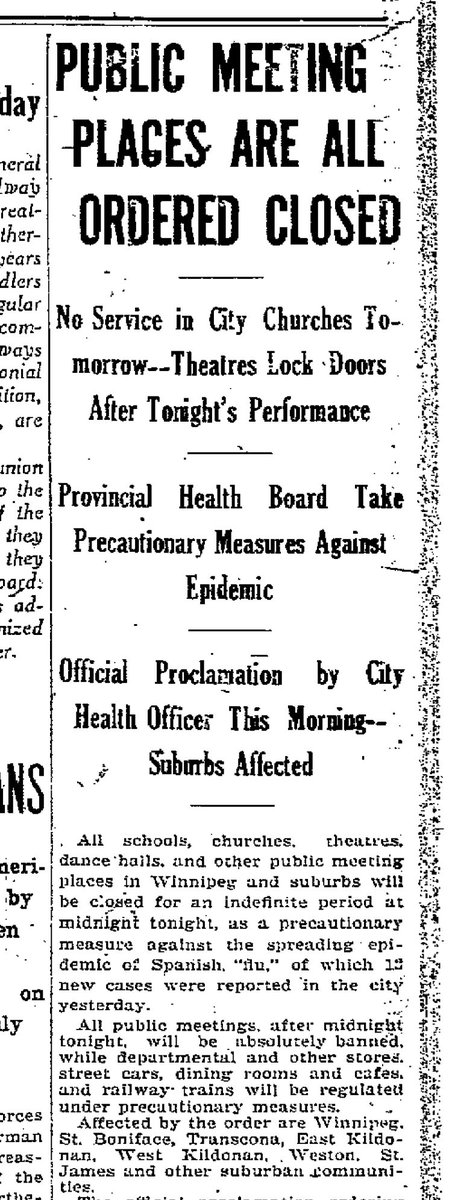

Framed as precautionary, the very next day, October 12, 1918, the order went out to close all public places to reduce the spread of the Spanish Flu in Winnipeg.

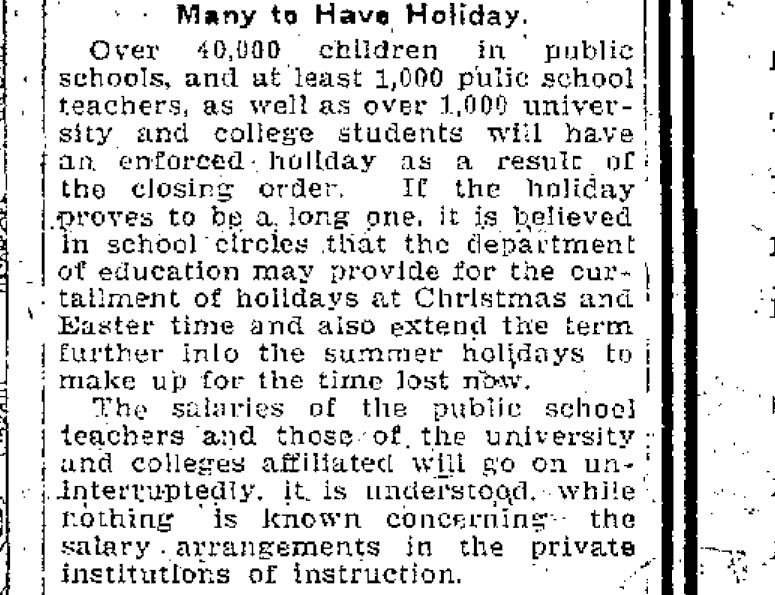

Schools were closed, giving 40,000 students, 1,000 teachers, and 1,000 university students an ‘enforced holiday’. Teacher’s pay was uninterrupted.

An interesting quote from church groups imploring people to act. ‘That one takes reasonable precautions is not a mark of fear; to refuse to take them is a mark of folly. Sometimes the fear of fear, assumes such proportions that it becomes folly’.

Motion picture houses and Legitimate theatres were closed. 400 to 500 men and women were put out of work.

Vaudeville acts and other touring groups to play at Winnipeg’s various theatres by-passed the city, heading to other places that had not yet been closed.

Similar to today, gathering in groups on the streets was prohibited and restaurants were limited in their operations.

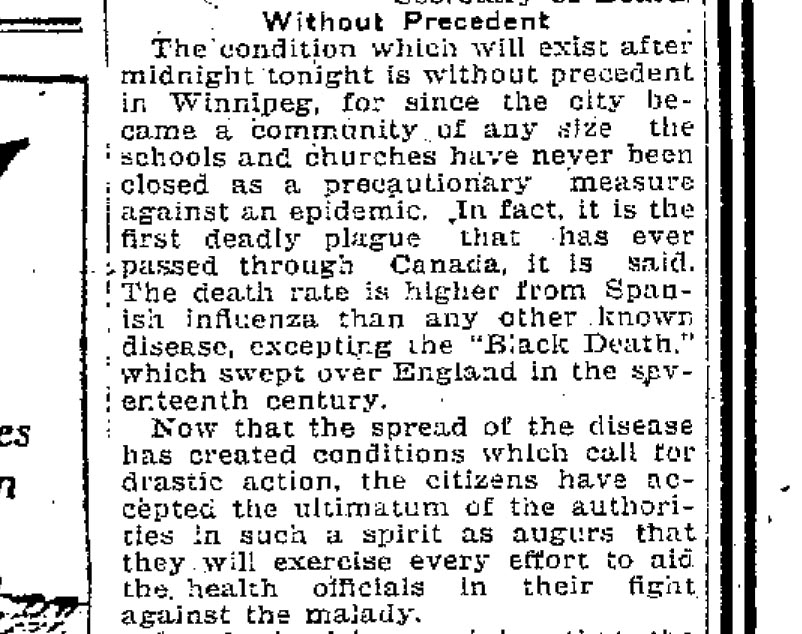

The move was ‘without precedent, for since the city became a community of any size, the schools and churches have never been closed’.

The economic hardships of a shutdown were well understood, but seen as necessary to protect public health.

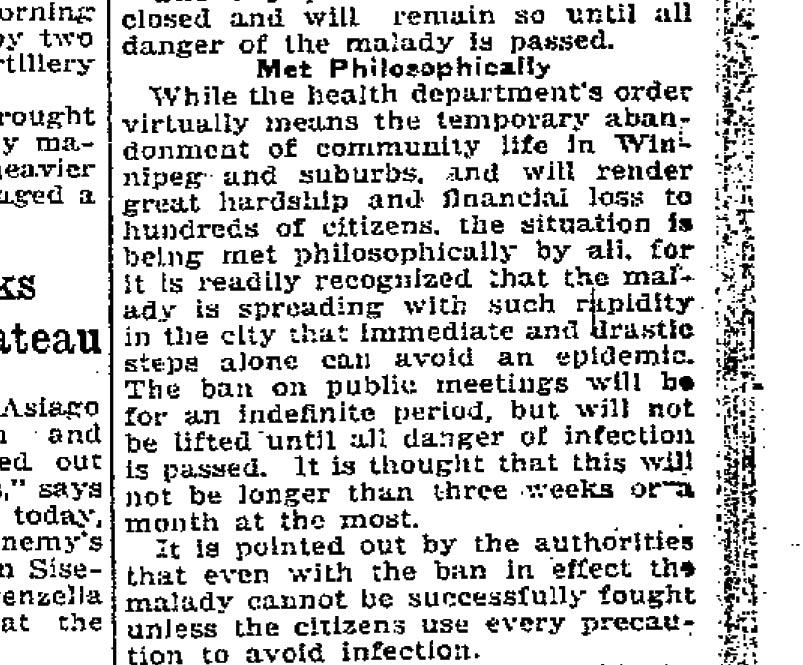

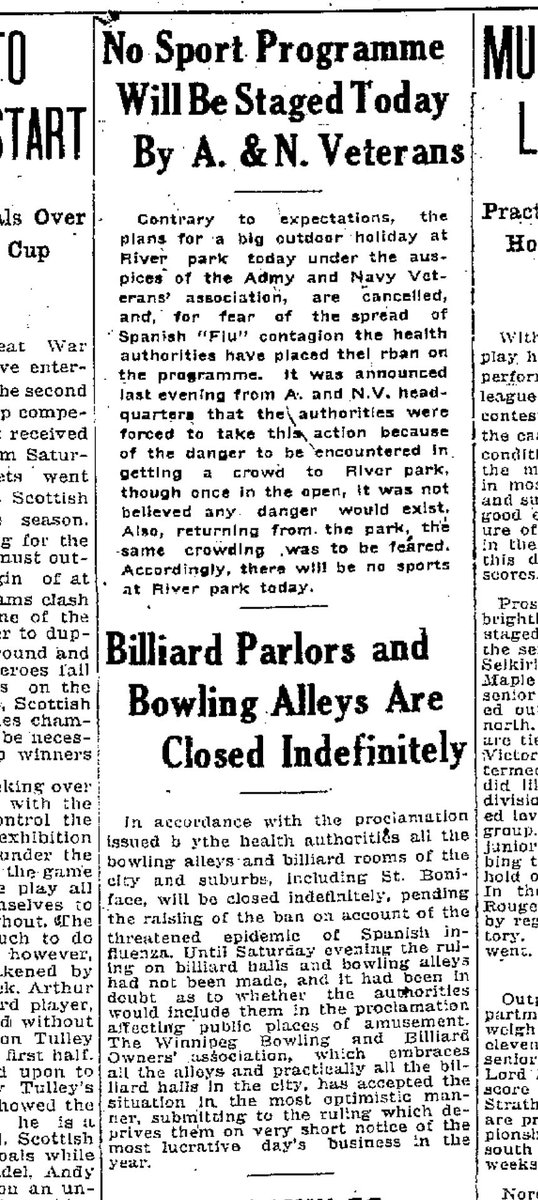

As the days passed, other things like sporting events, bowling alleys and billiard rooms (which were considered sports) were closed and cancelled.

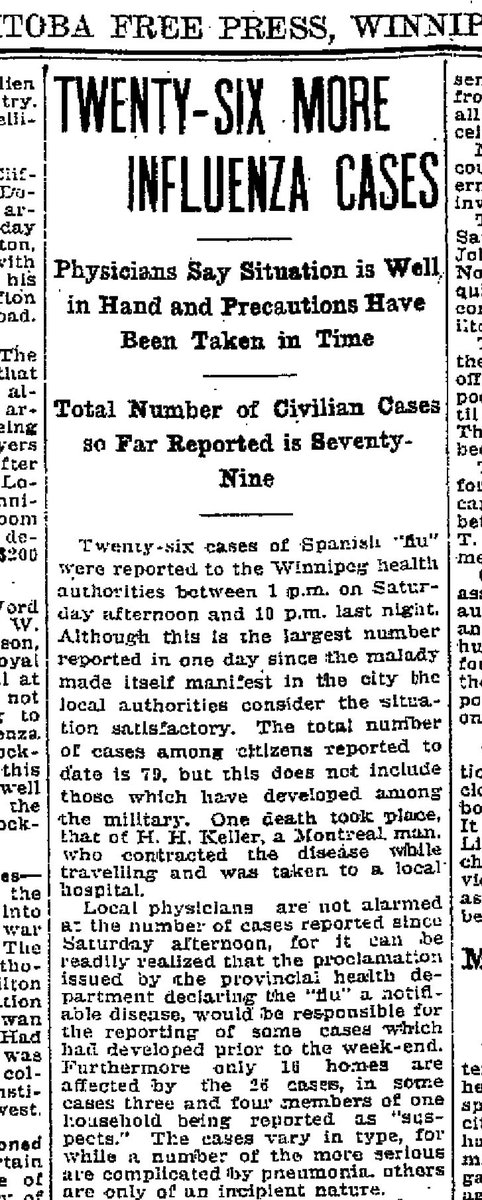

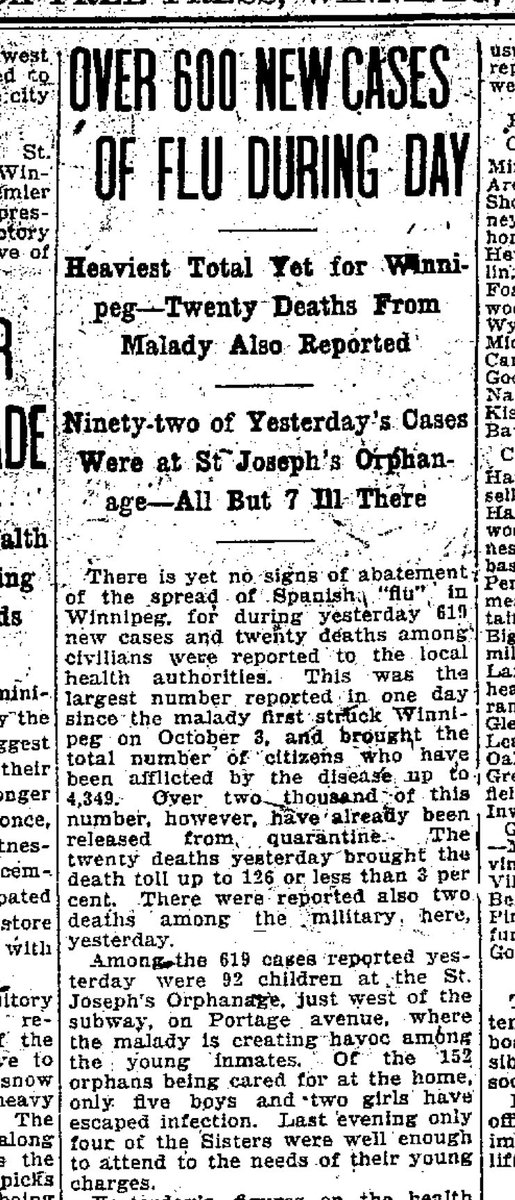

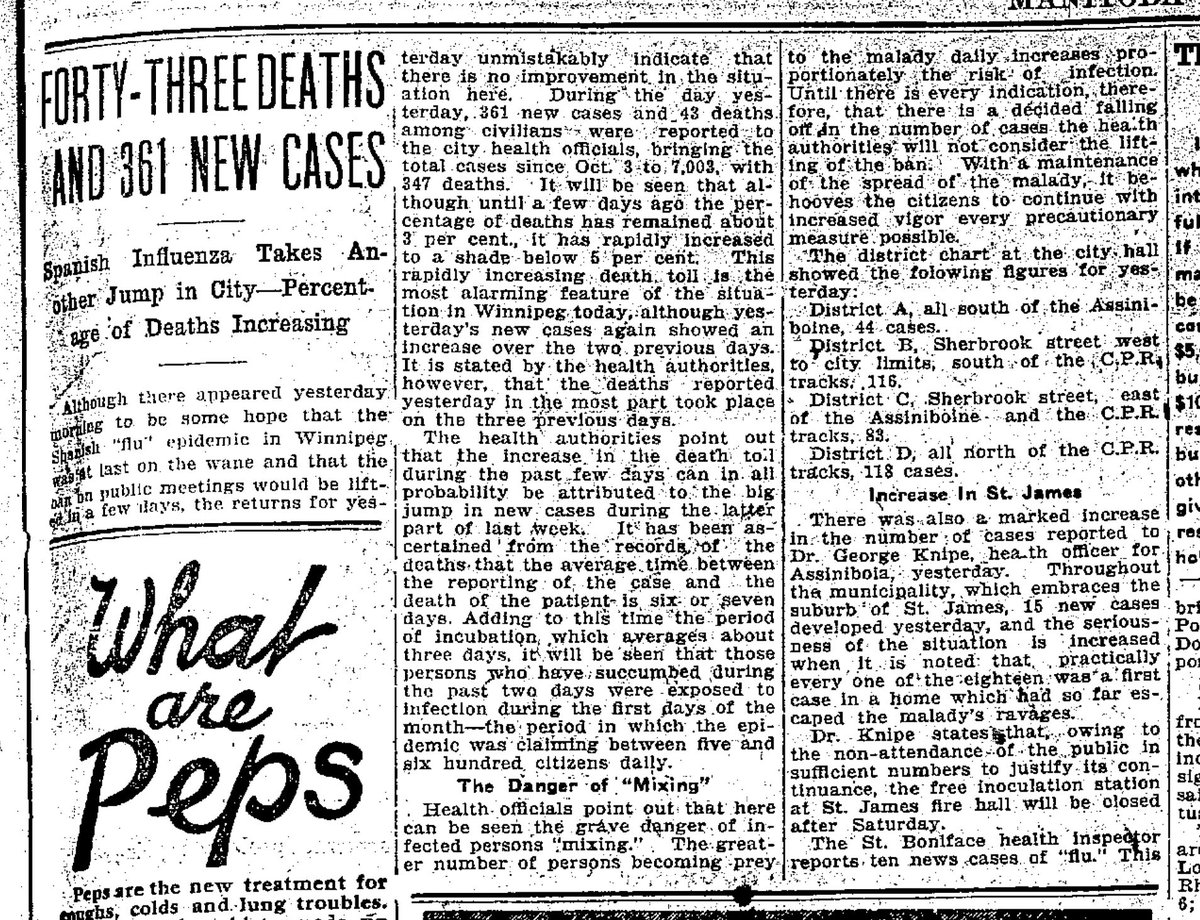

From October 12 on, the Spanish Flu pandemic in Winnipeg began to grow. Very much like today, the headlines each day counted the number of new and cumulative cases and deaths, always looking for the trend. (Oct 14)

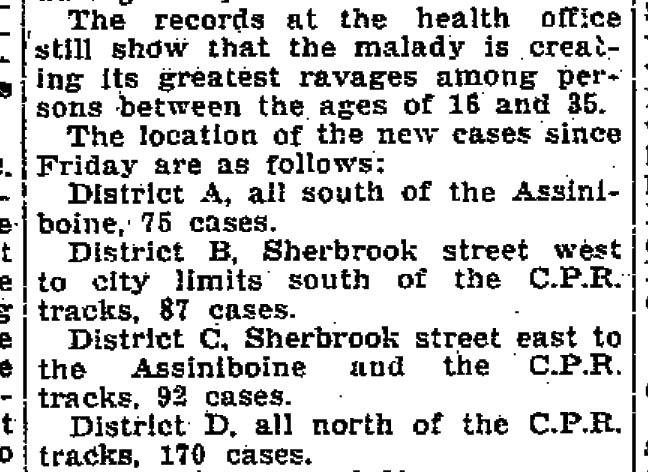

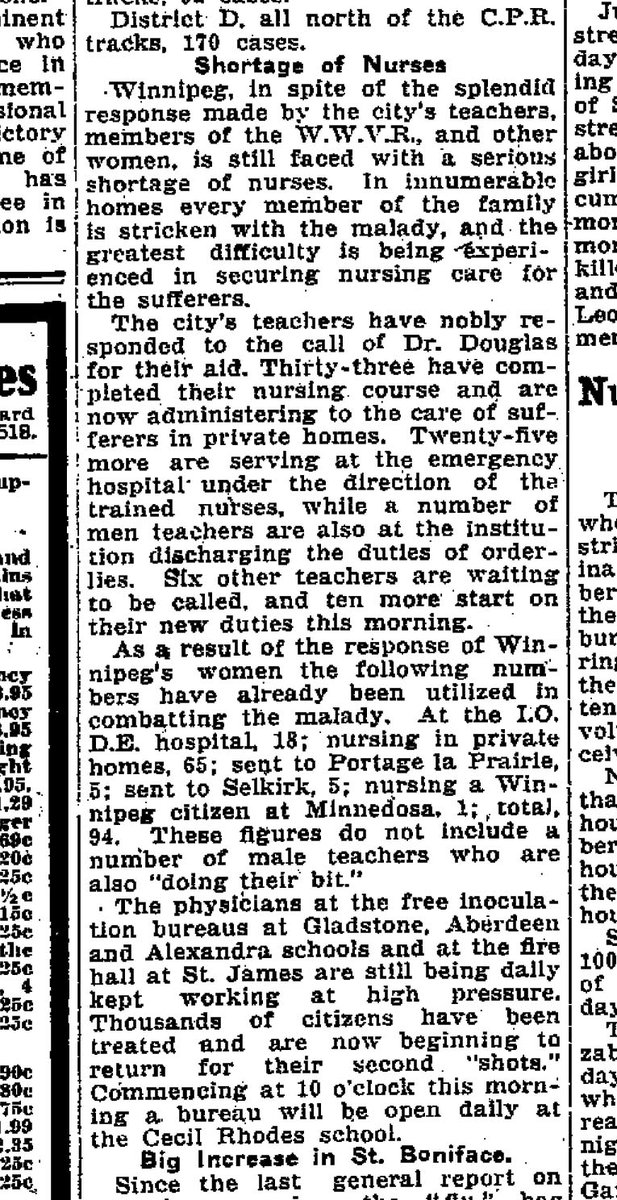

New cases were tracked in different quadrants of the city, reported each day. The North End was hit hardest.

On October 17 the health authority allowed city council to meet to pass bills to help struggling businesses.

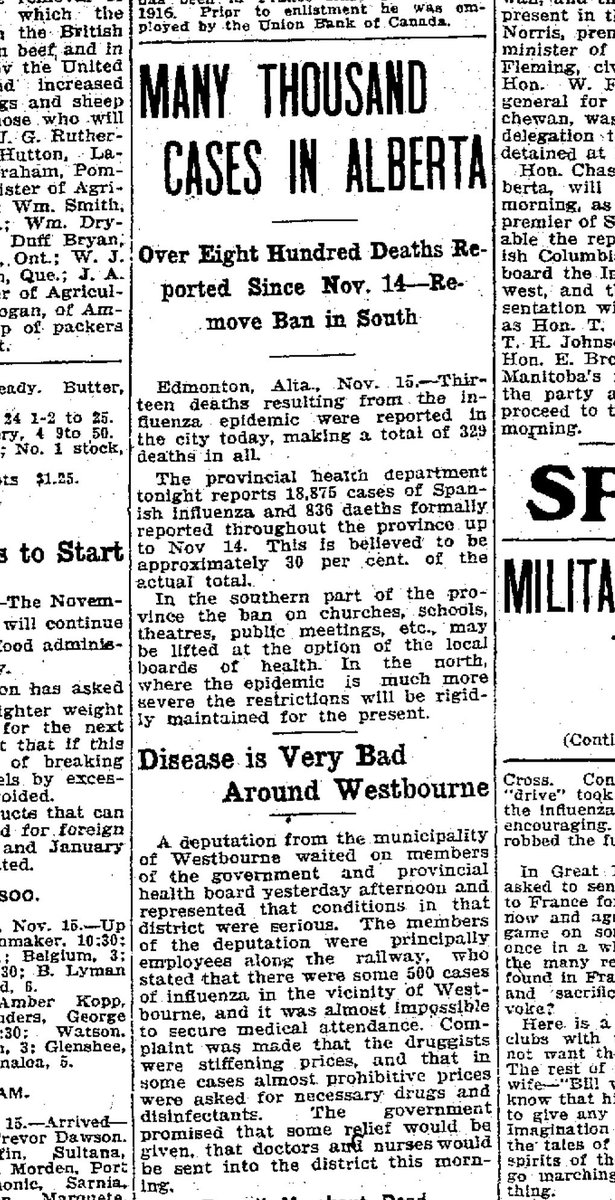

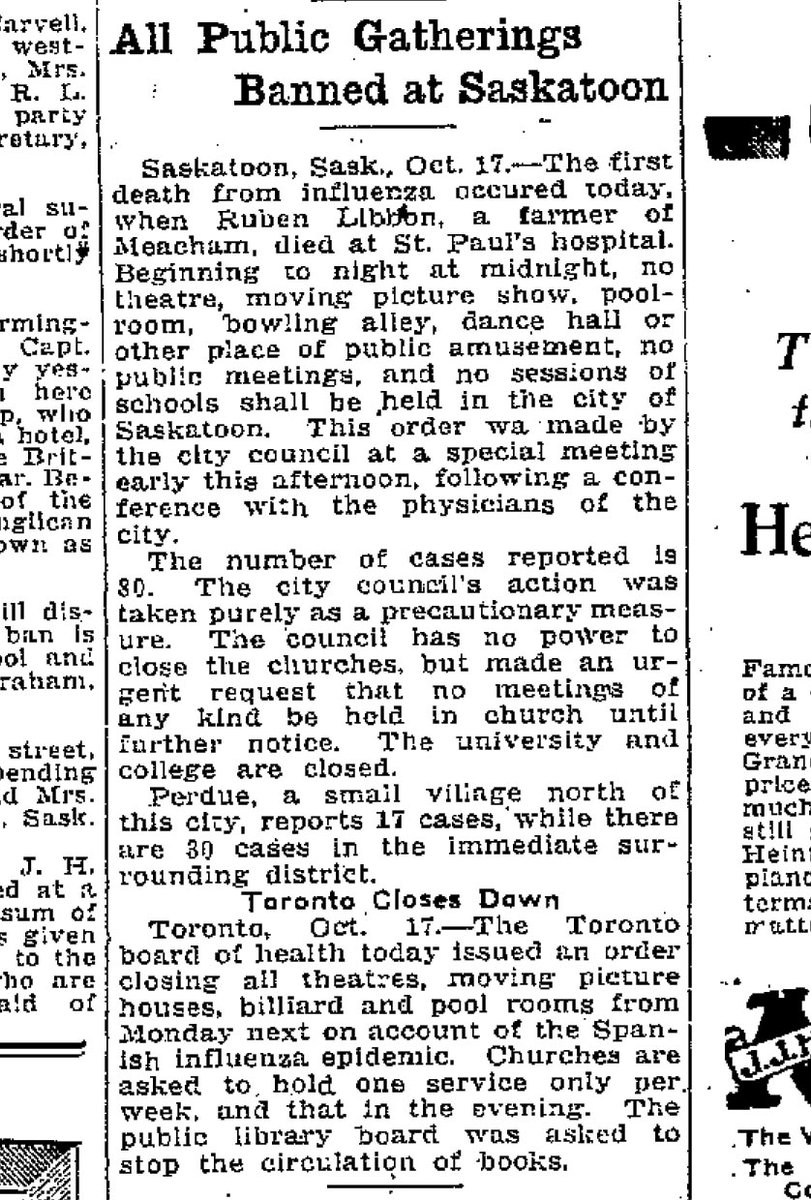

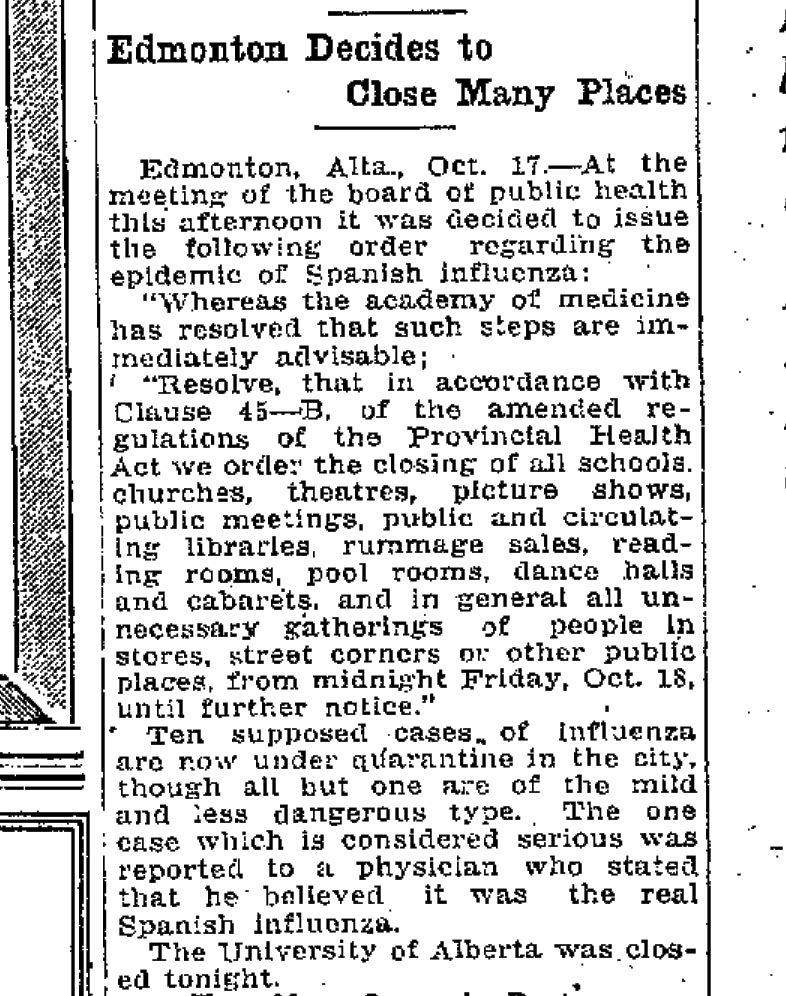

The newspapers watched closely what was happening across Canada. The fight against Spanish Flu was seen as a patriotic battle. This was happening at the same time as the war was ending.

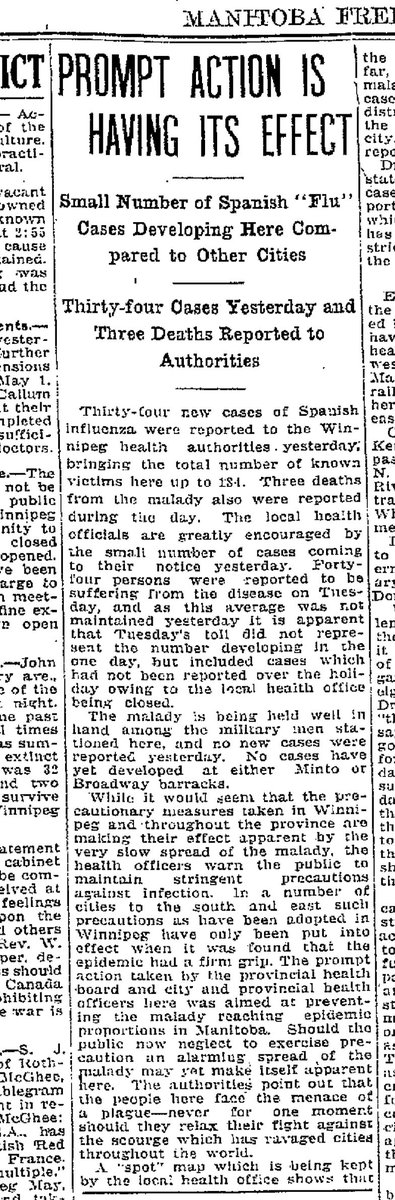

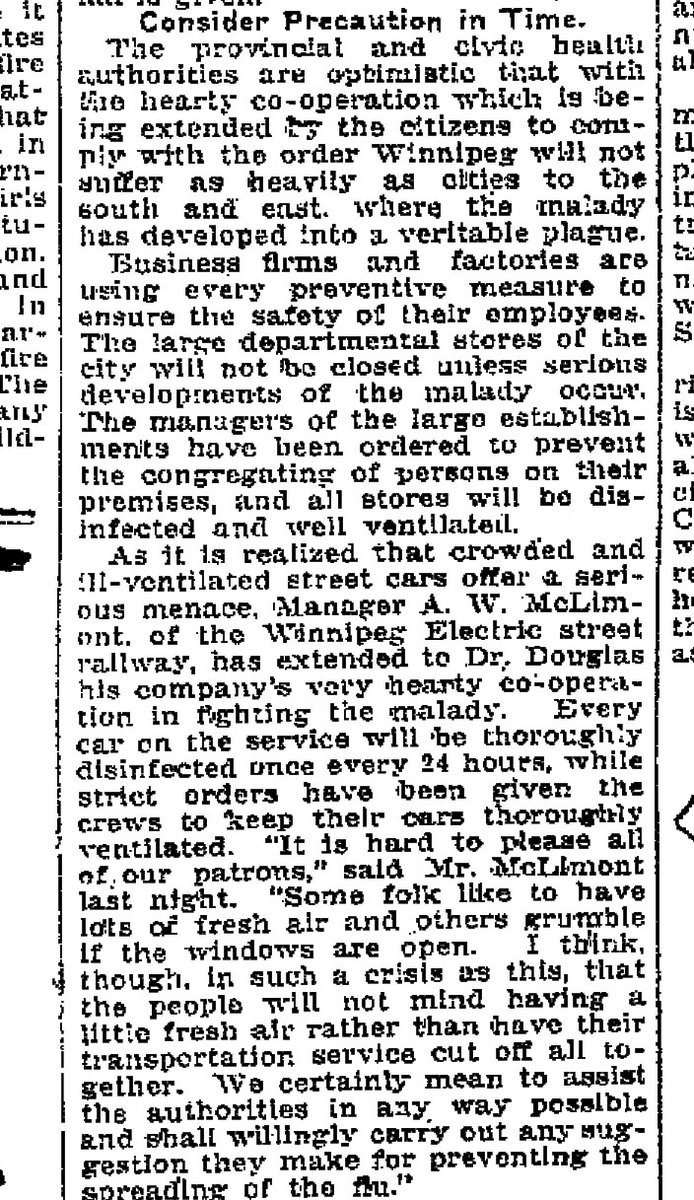

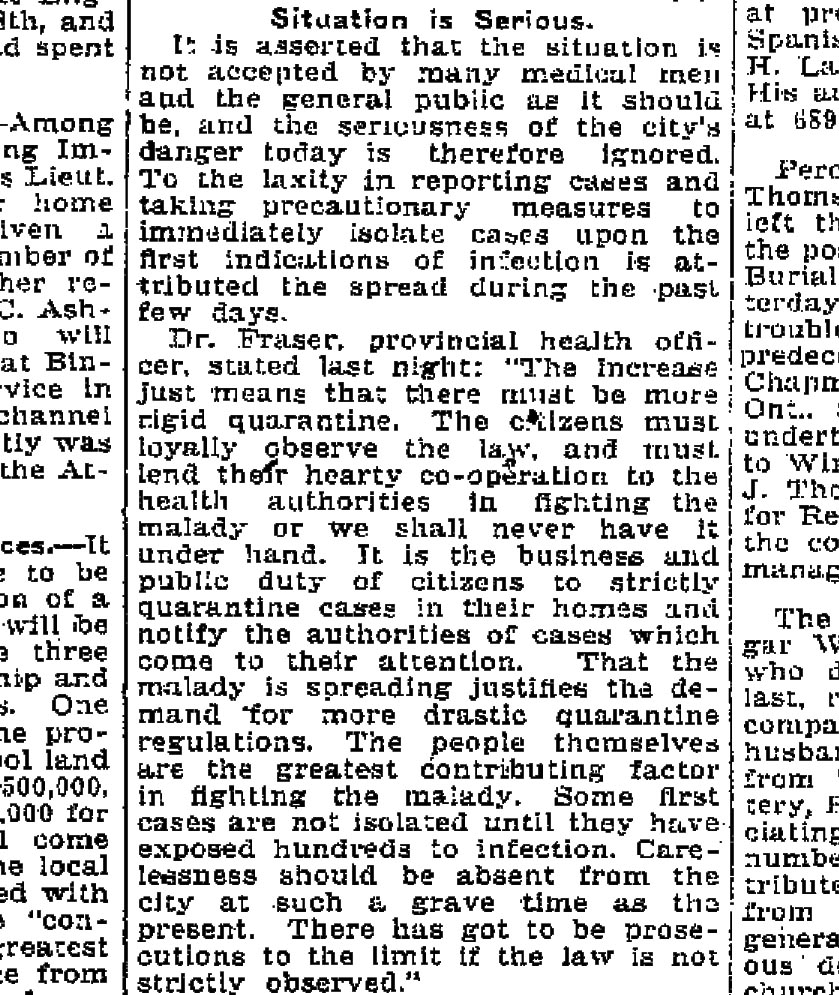

Like today, because cases grew slowly, there was early optimism in mid-October that the swift action of closing down the city immediately, learning from other cities because of its late arrival, meant they were flattening the curve and might be spared the brunt of the pandemic.

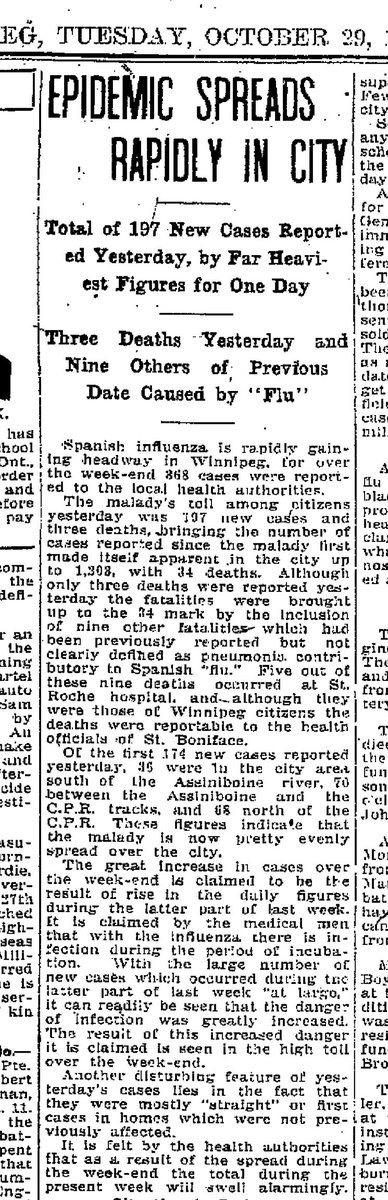

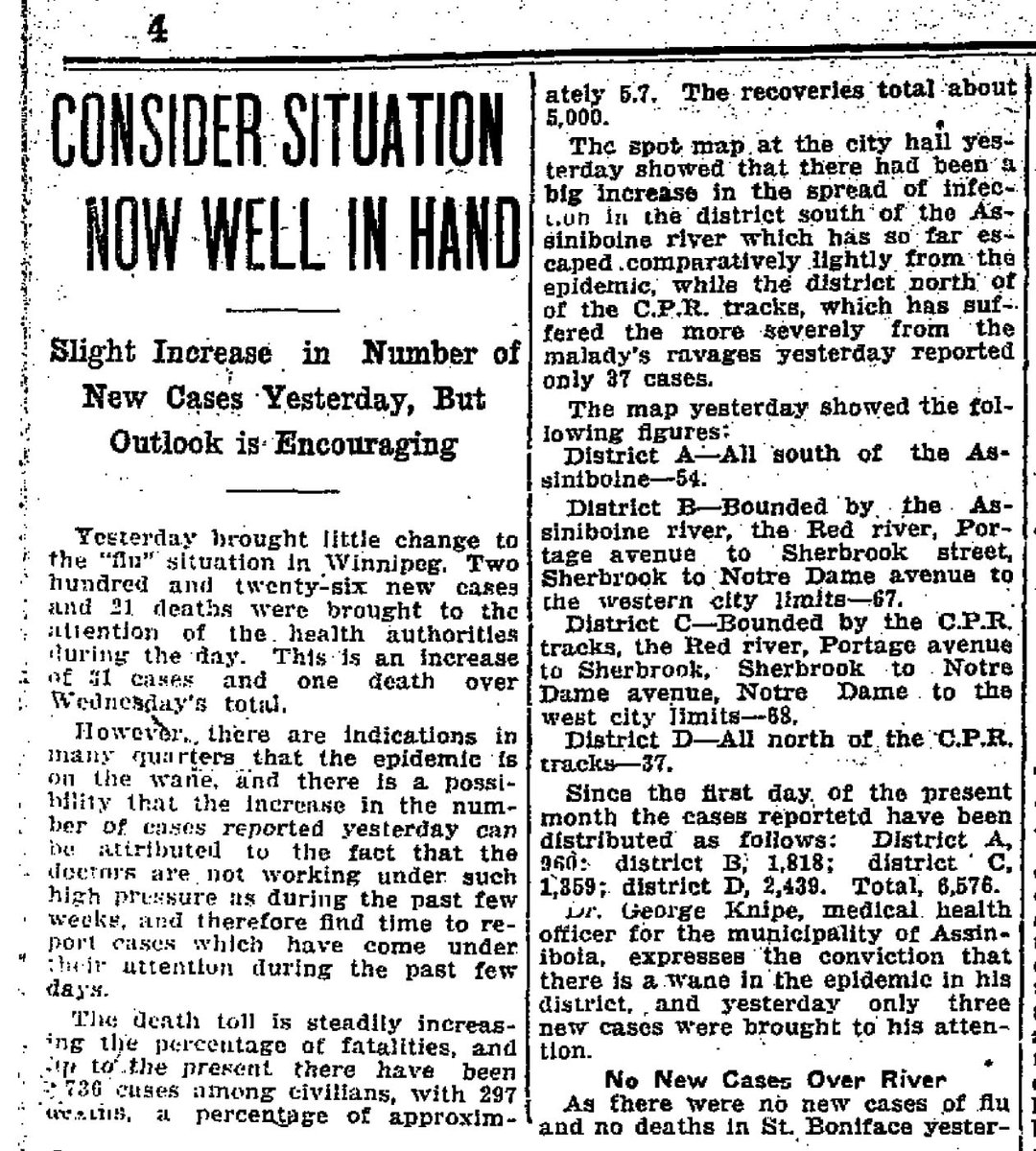

If the number of new cases went down one day, the headlines expressed optimism that the pandemic was passing, that optimism dashed as cases would invariably explode in the days to come. These headlines are from two consecutive days in late October.

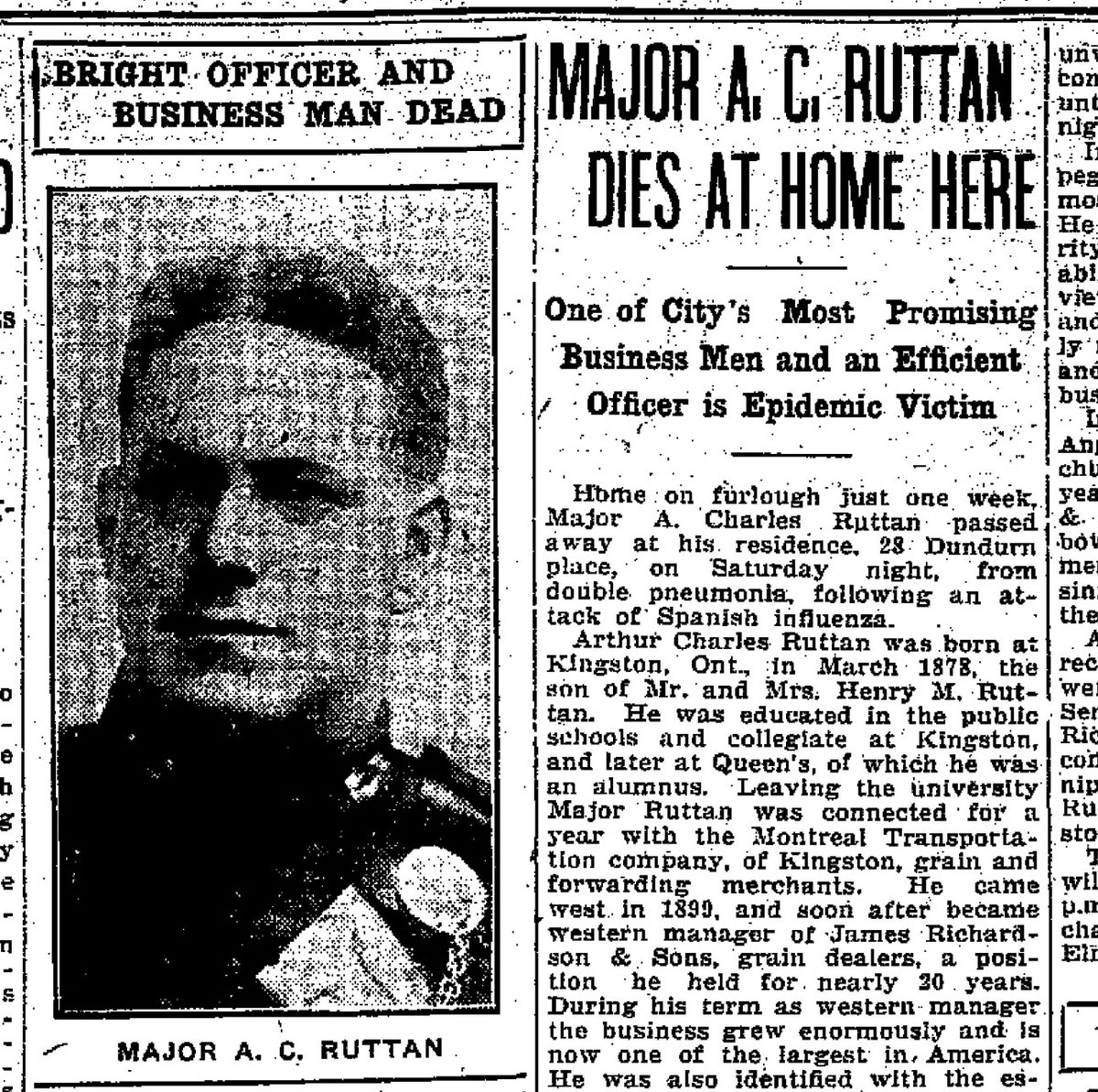

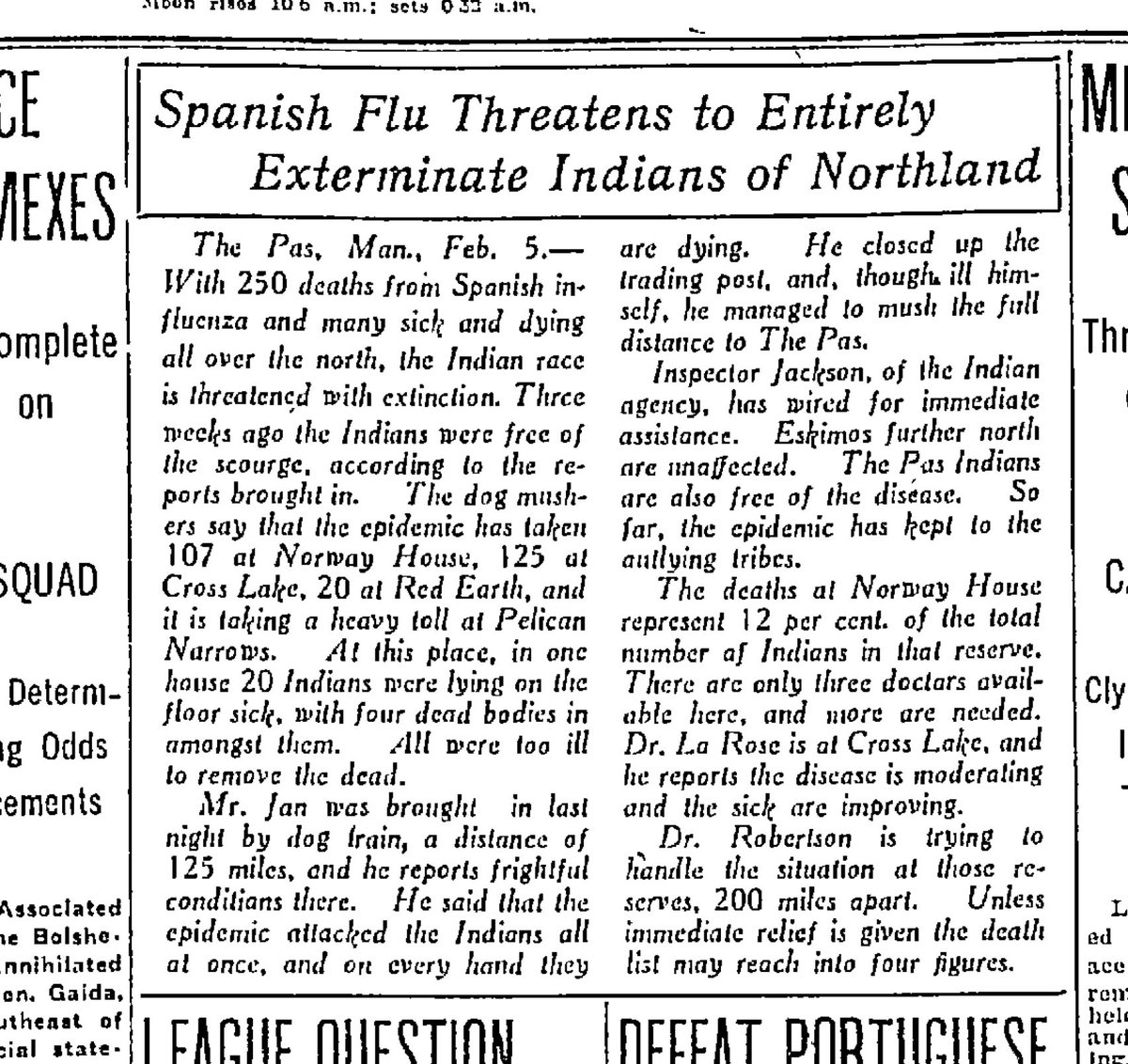

By late October thousands of Winnipeggers were sick and in quarantine. The newspaper became filled with notices of those who had succumbed to the virus.

Hospitals began to fill and run out of beds for patients. Two new makeshift hospitals were constructed within a week. They were almost immediately filled.

The Grain Exchange even took the drastic measure of restricting the smoking room to one person at a time.

In an 1918 version of on-line classes, the universities began assigning students work through the mail. ‘It is not expected that there will be any reduction in the amount of work to be covered’

Articles with instructions on how to treat the Spanish Flu appeared regularly. ‘Avoid crowds, coughs and cowards, but fear neither germs nor Germans.’ – remember the Great War was happening at the same time.

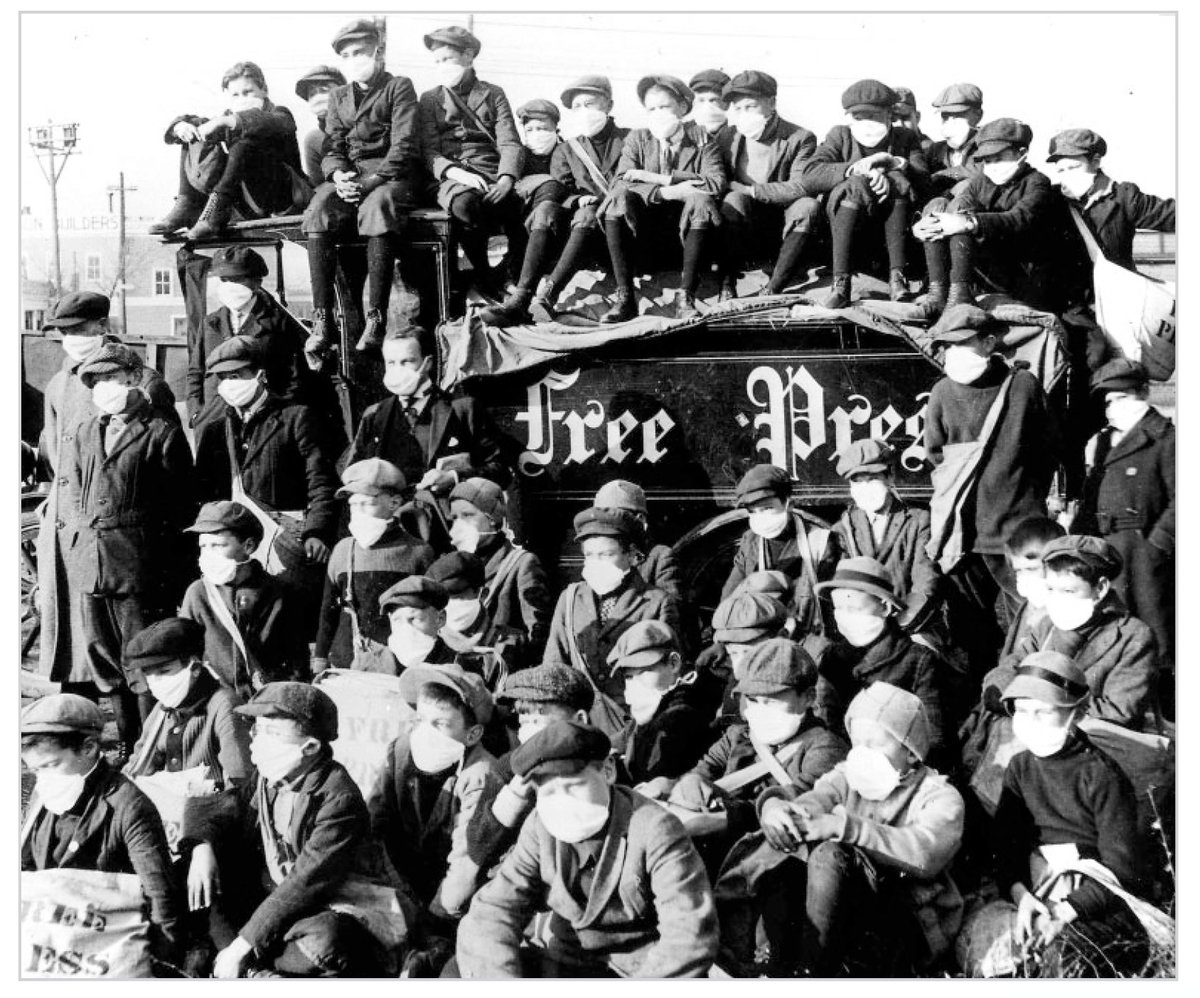

Like today, there was debate about wearing masks in public places, with the health officer proclaiming that everyone riding in street cars should be wearing one.

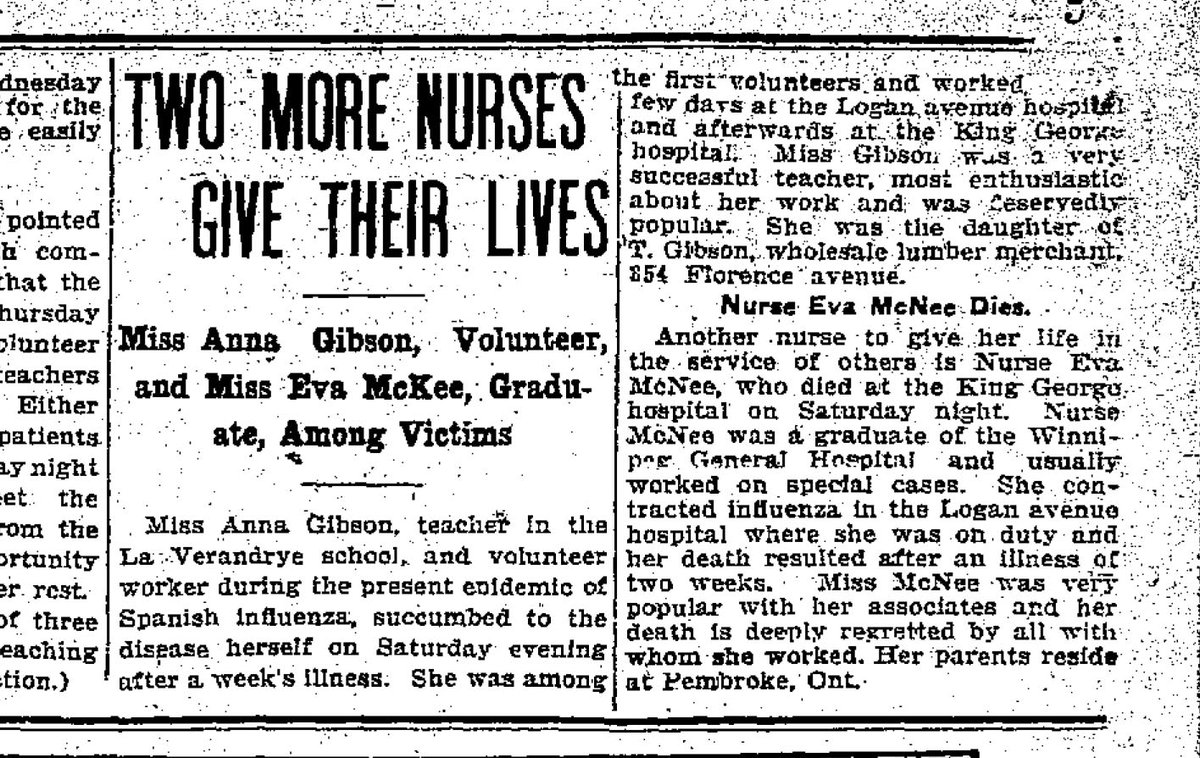

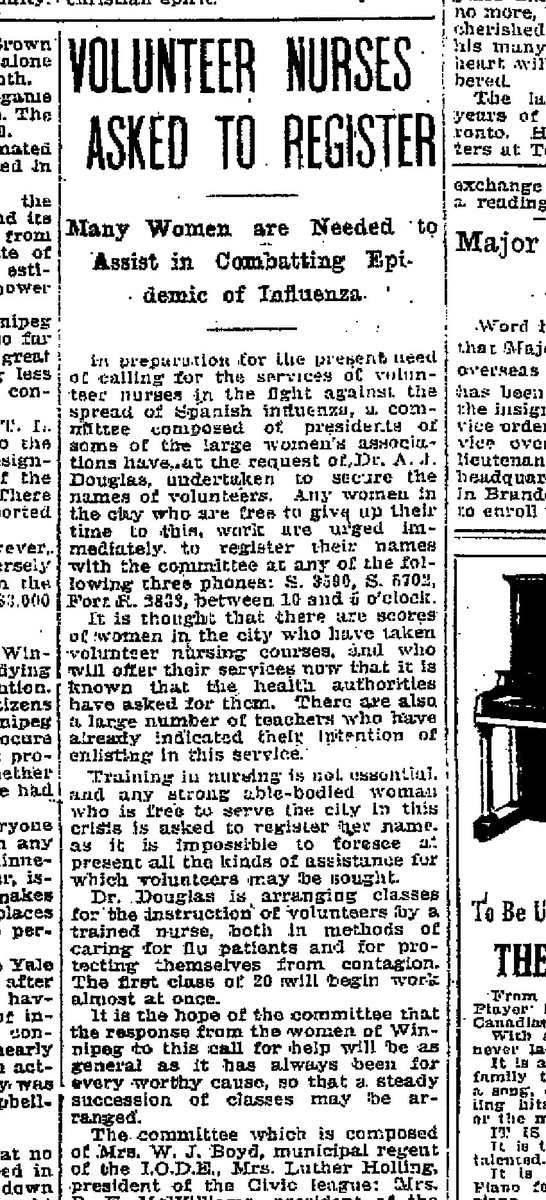

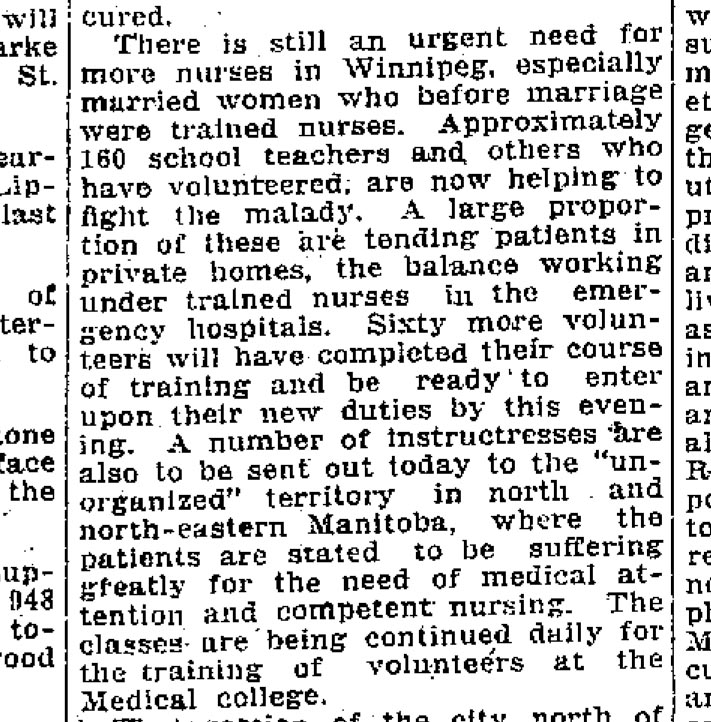

The city put out a desperate call to women to become volunteer nurses, included those trained as nurses before marriage. Emergency training classes were organized. Teachers (because they were mostly women) were asked to volunteer. Most bravely did.

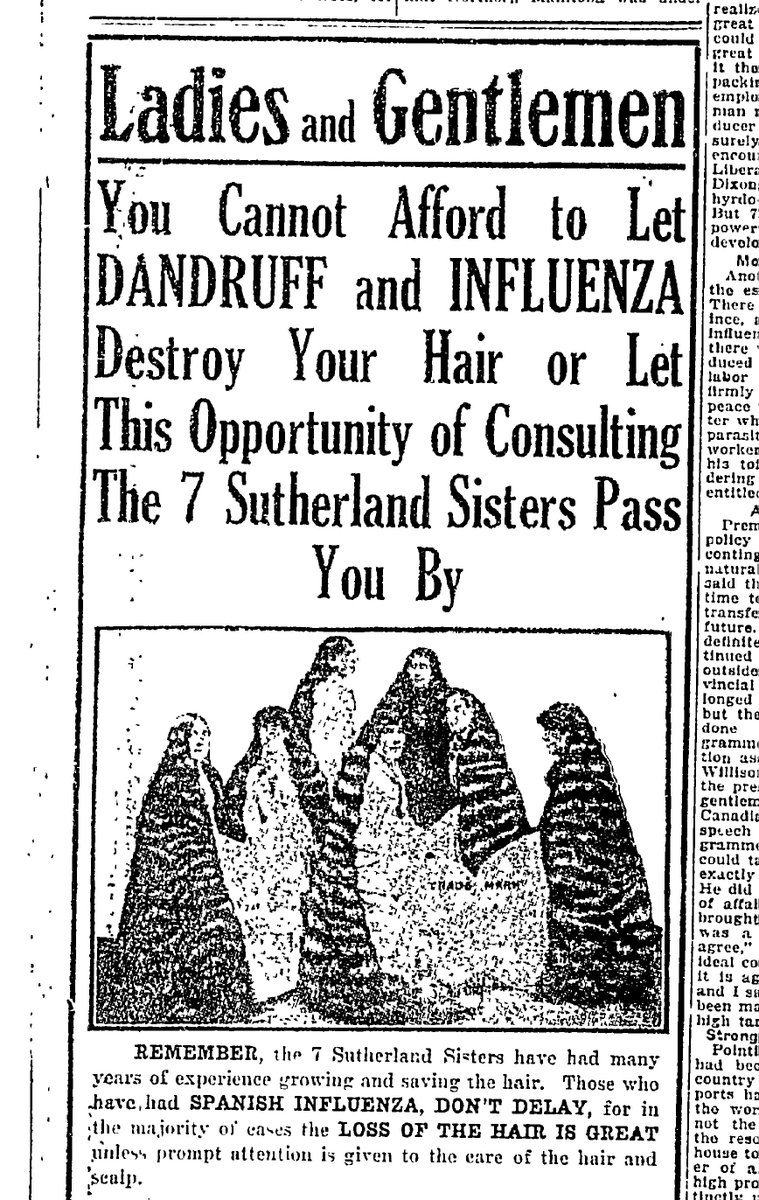

The effects of the lock down were taking their toll. People were concerned about their hair (some things don’t change).

Theatre employees were desperately asking for help from the city, theatre operators asking for help from landlords.

Might as well have the flu as to be bored to death – but a box of Affinite Chocolates and a good book or magazine will make staying at home nights a real treat.

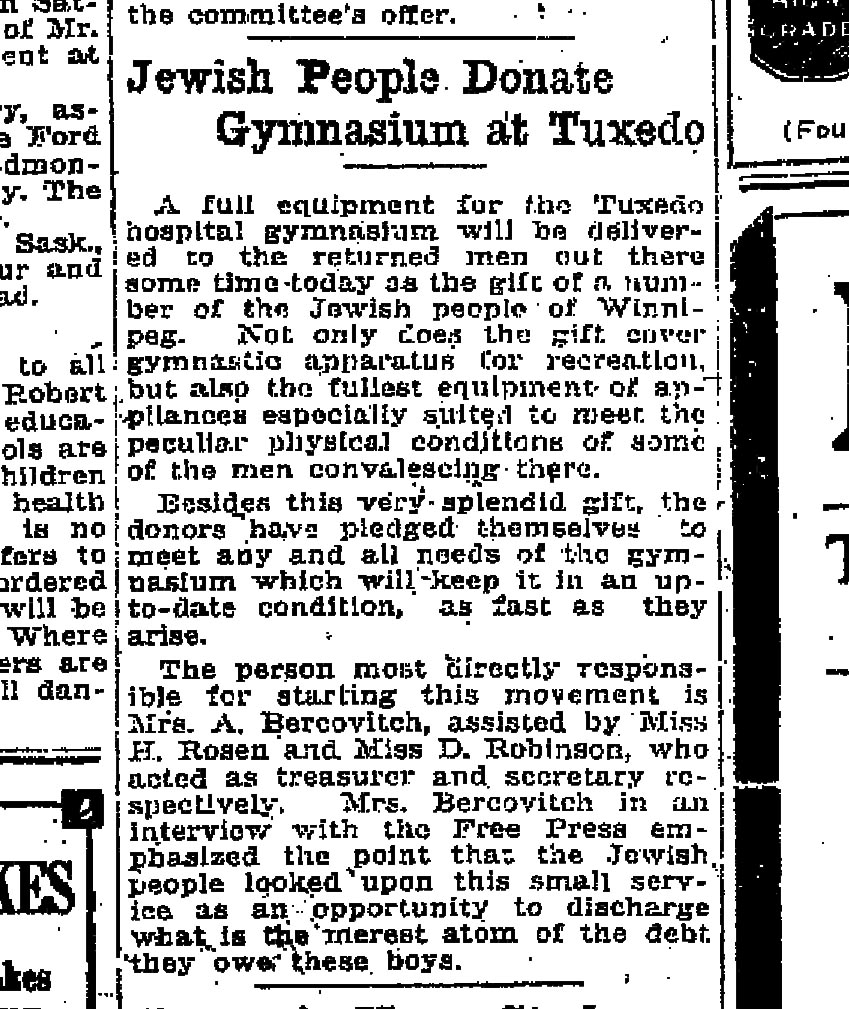

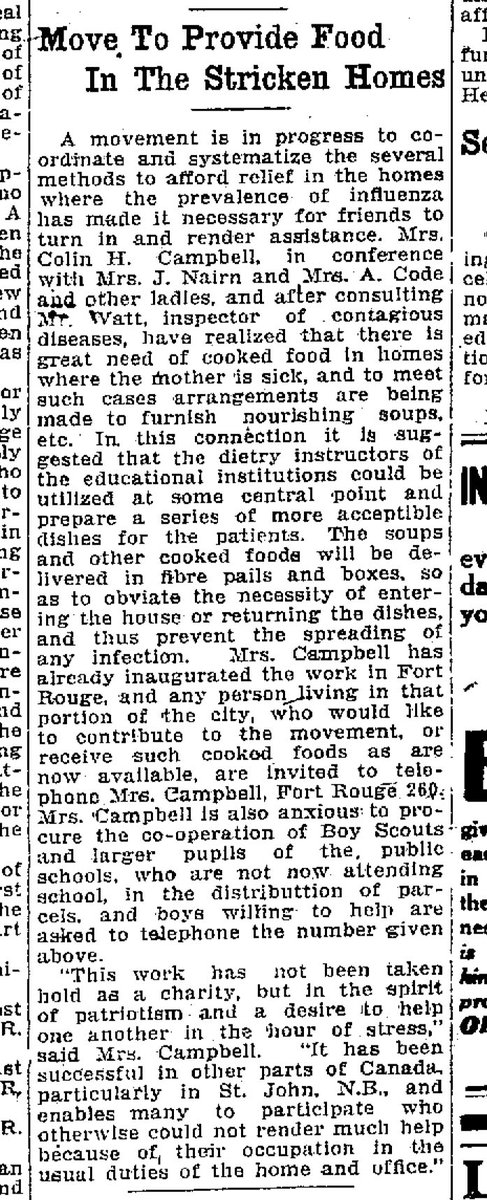

The community banded together in crisis. The Jewish community donated gym equipment to the hospital, and women organized to provide food to families in which the mother had been struck down with illness.

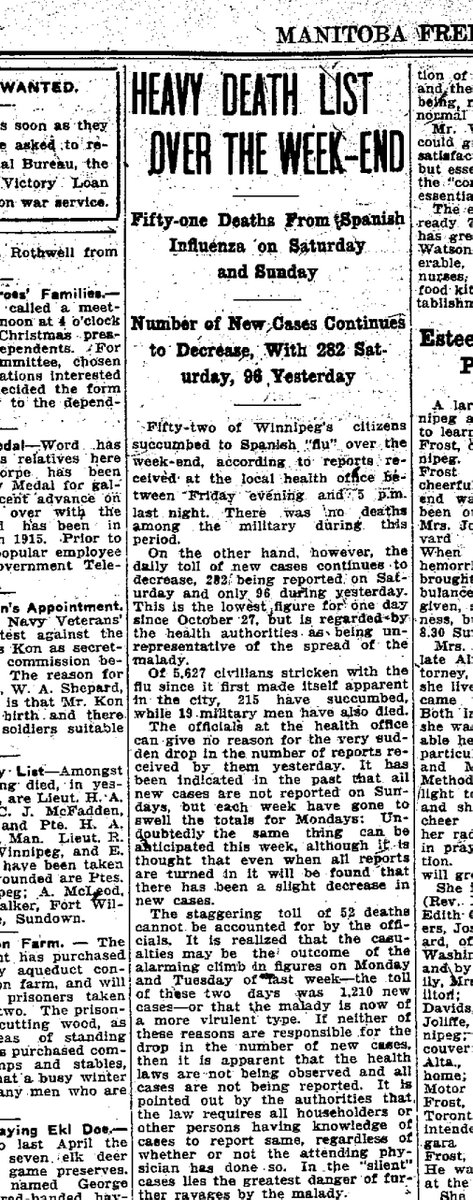

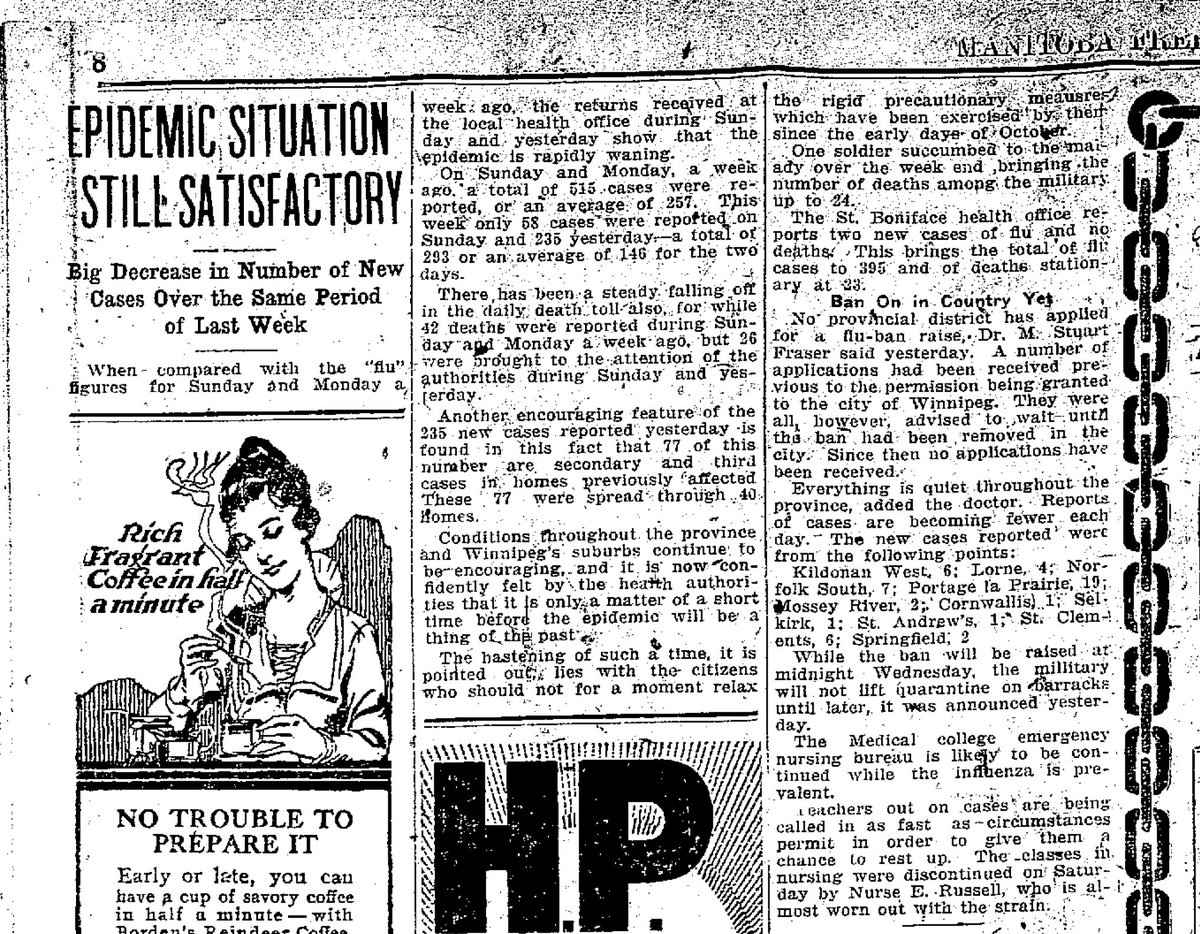

By mid-November the daily death toll was still very high, more than 50 deaths per day, but the occurrence of new cases appeared to be levelling off.

By November 22 the debate had begun to lift the lock down and let people move around more freely again. The spread was quickly decreasing.

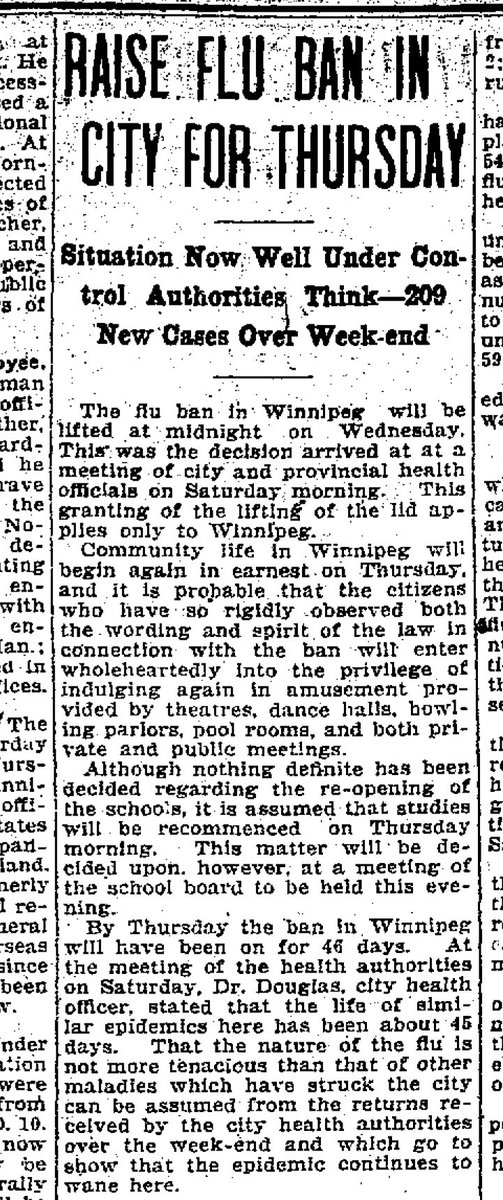

On November 28 the Flu Ban was lifted. It had been in place for 46 days. New cases and deaths were still occurring by the hundreds but it was on the decline and the desire was strong to return to normal.

Schools were kept closed for another week, so the teachers that had become nurses could continue helping the sick.

As the Flu Ban was lifted, 9,131 people had been struck by the Spanish Flu and 550 Winnipeggers had died in the previous seven weeks. More than 3,000 more people would become sick and 300 more would die before the pandemic was over by mid 1919.

Some precautions remained in place. Shoppers were urged by the health authority to do their Christmas shopping early and distribute it over a longer period of time to reduce the typical December crowds.

In the end, more than 12,000 people got sick and 824 people died of the Spanish Flu in Winnipeg. Across the world 50 million people died, making it a larger killer than the Great War.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter