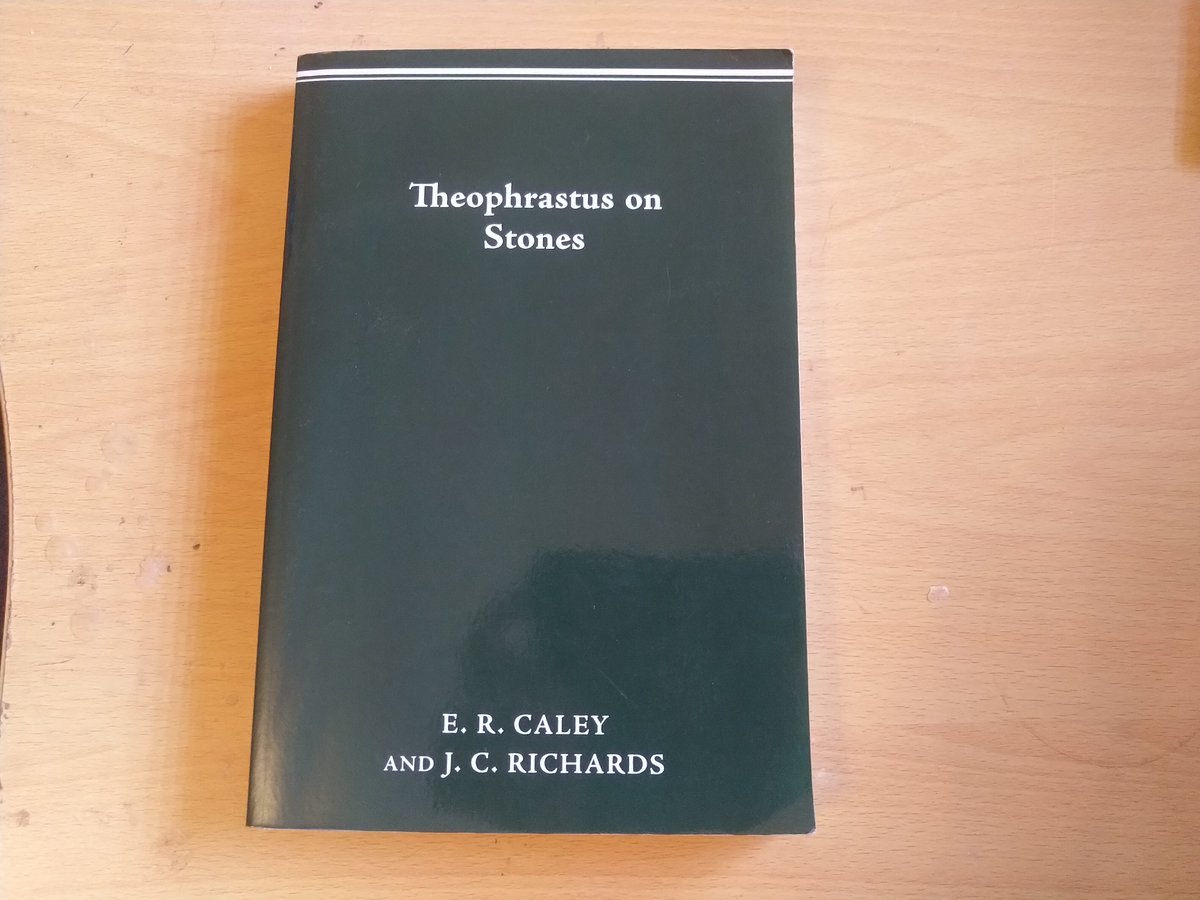

Thread: The books that matter. These are extant texts; I might do another one for modern books. First, Theophrastus - in reality, only a few pages of descriptions of minerals, but with a detailed commentary by the translators. Caley also translated the Leyden & Stockholm papyrii.

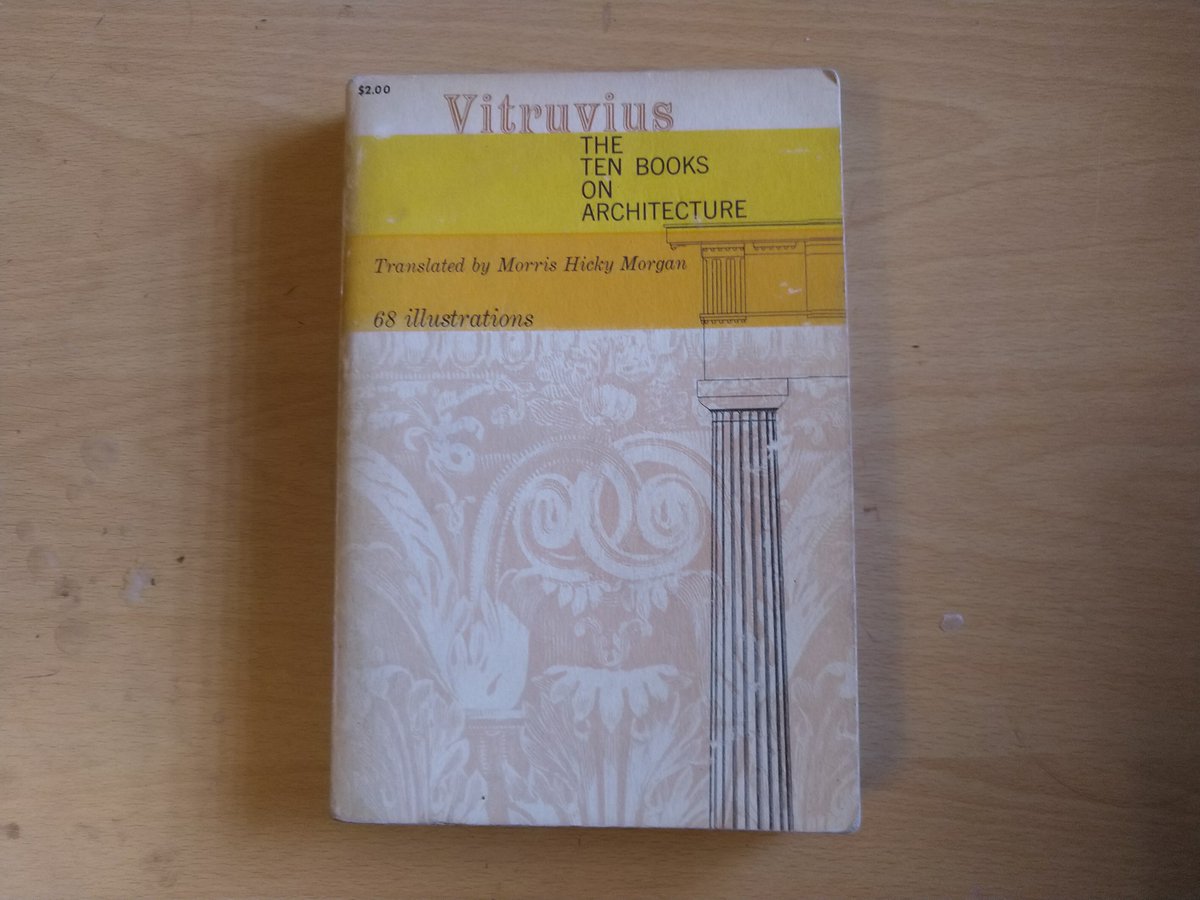

Vitruvius. You may be thinking...these are not metalworking texts, but this, & #39;On Stones& #39;, and & #39;De Materia Medica& #39; touch on relevant subjects, and are full of interesting details about the uses of different minerals and synthesised chemicals, before the Middle Ages.

Then, a gap. I don& #39;t have a print copy of the Leyden & Stockholm papyrii, but it would go here. Recipes for fraudulent work with precious metals and gemstones, as well as other things. There were perhaps other documents, that bridge the centuries, but this gap is a long one.

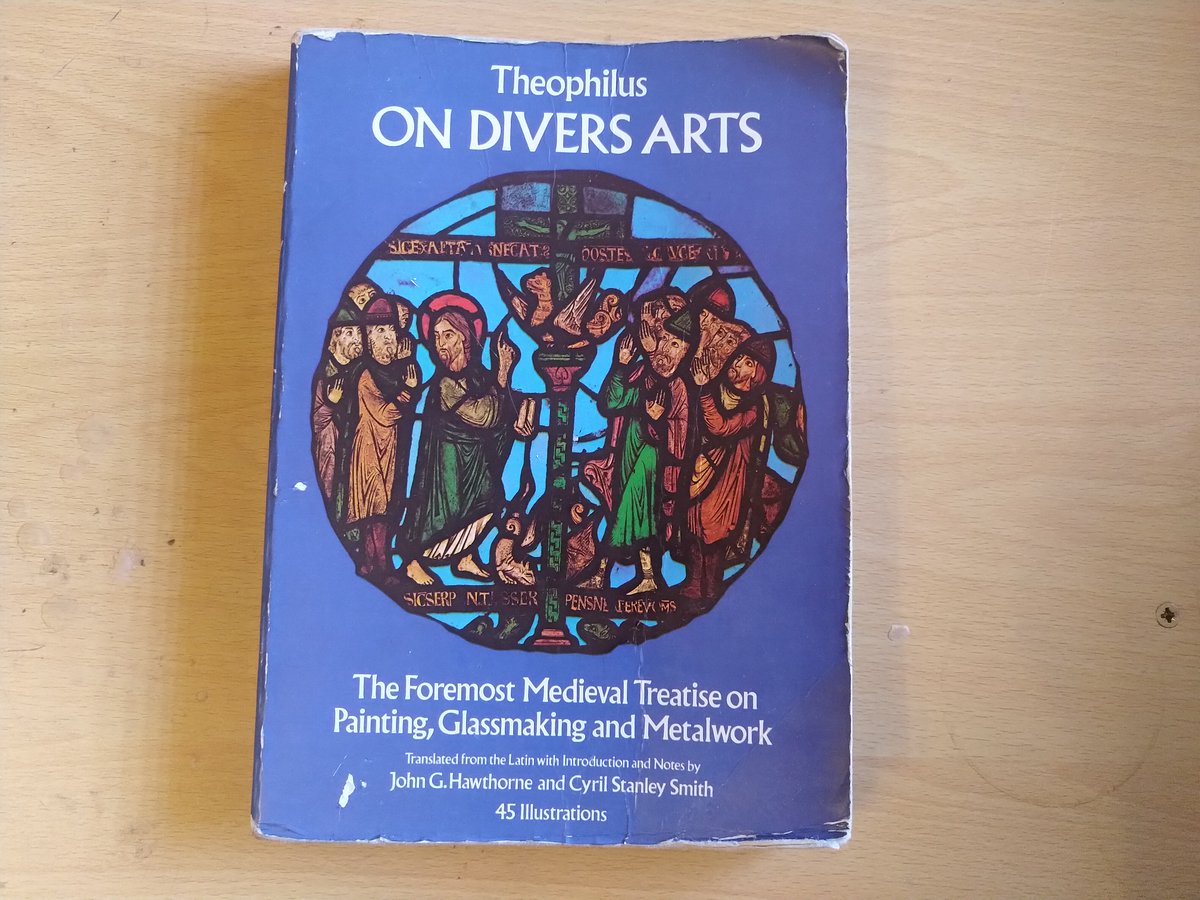

In the early 12thC, we get this, which is the BEST BOOK EVER. 3 sections, on painting, glass, and metal, and written so that you can establish a monastic workshop of your very own. This is a technical translation, by the American metallurgist, Cyril Stanley Smith.

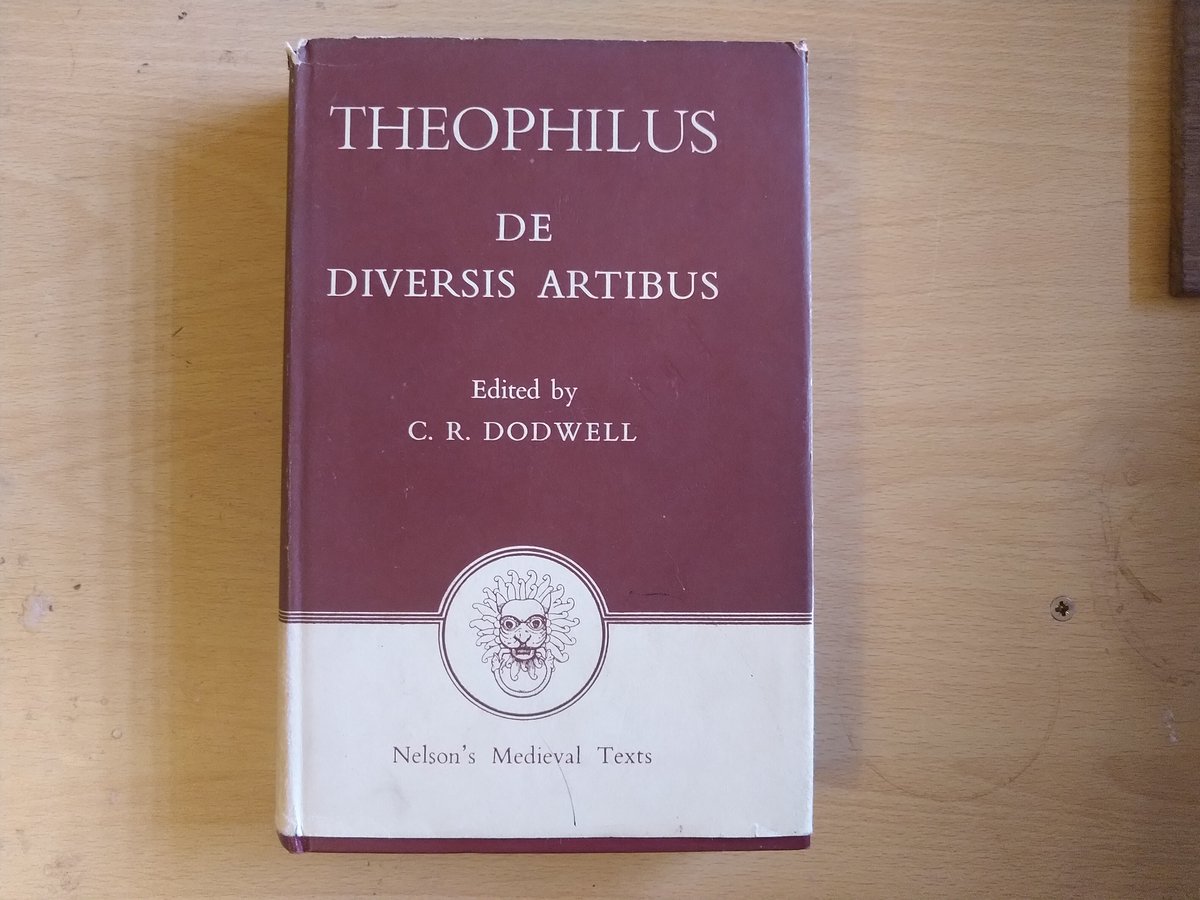

This is Dodwell& #39;s linguistic translation of the same, which includes the Latin text, which faces the English translation on every page. Even someone as clueless as me can benefit from this - but it& #39;s not the copy that I read for fun*!

* For any given value of & #39;fun& #39;.

* For any given value of & #39;fun& #39;.

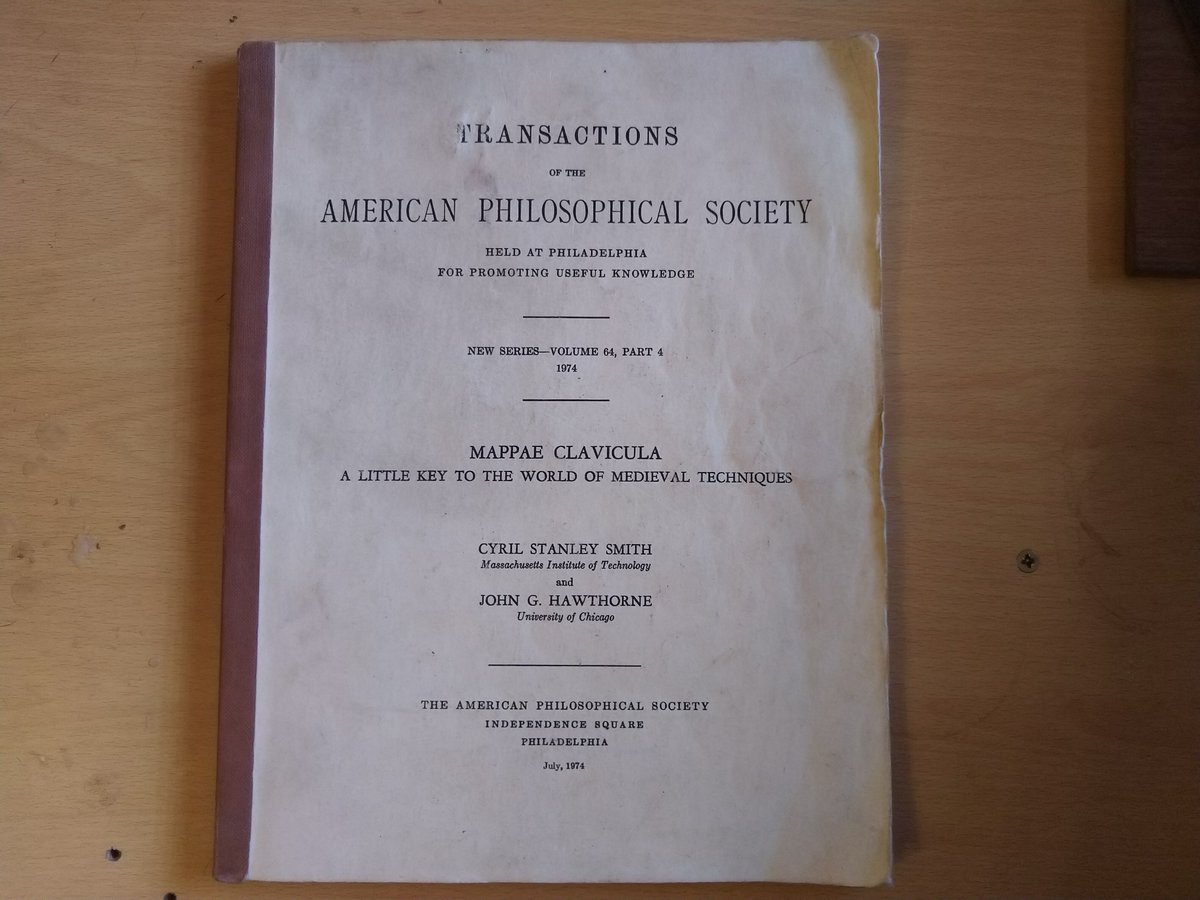

Arguably the older text, this is nonetheless a translation of the 12thC Phillips-Corning MS. A delightful book of recipes, but not a workshop manual, by any means. It has been suggested that it& #39;s role was as a glossary, rather than for practical use, but most of it is usable.

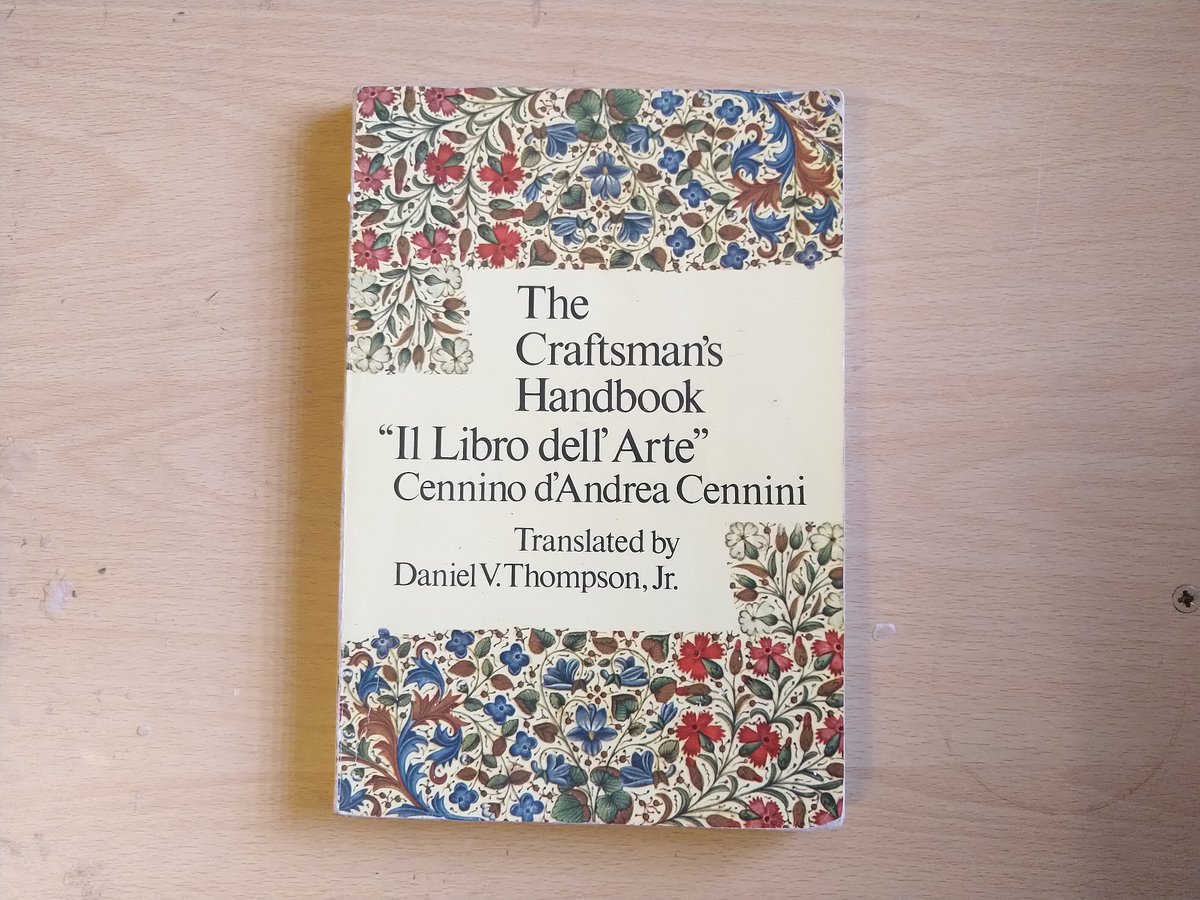

Another gap. Cennini& #39;s book is entirely aimed at painters, or the young men who wish to be painters, and should definitely not be associating with women, or having any fun at all, if they want to be great artists. He& #39;s probably right, tbf.

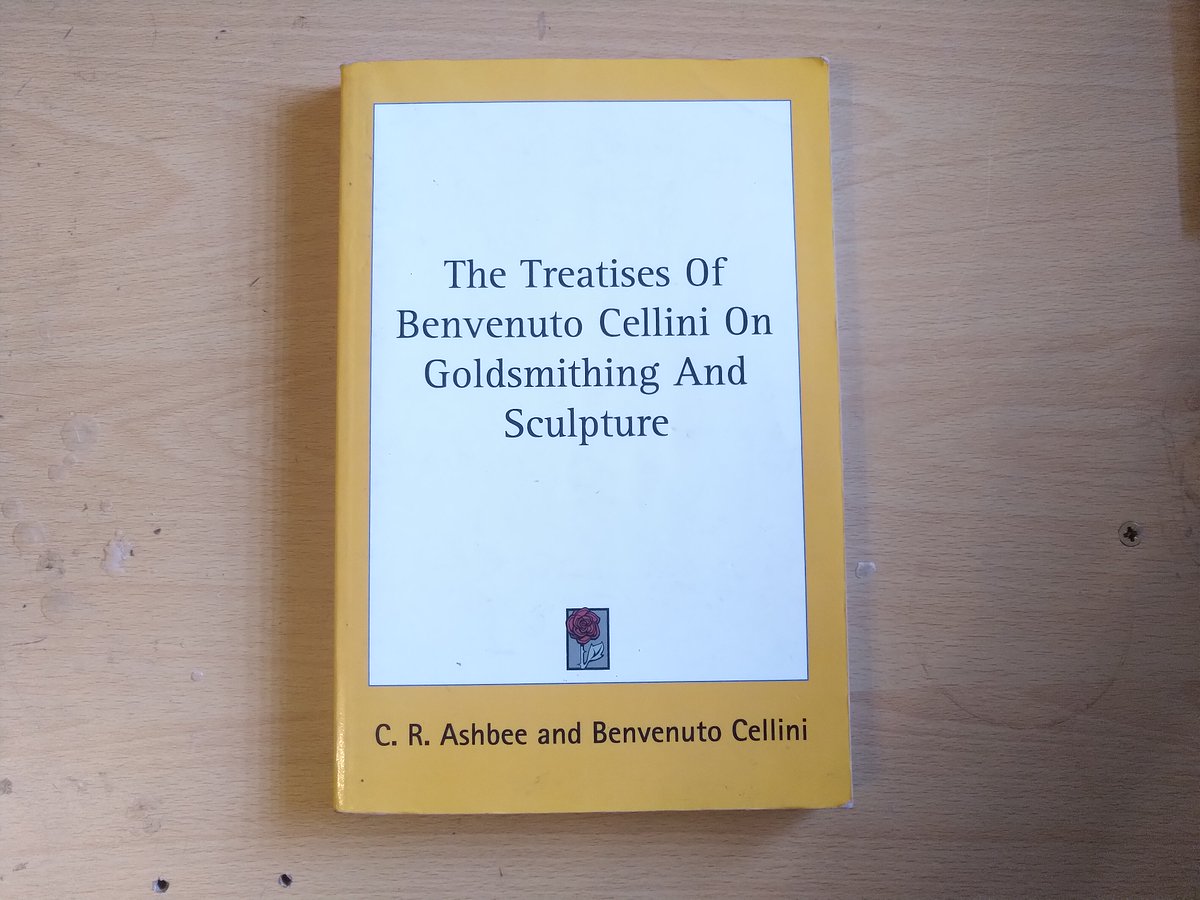

A detailed and very practical guide.

A detailed and very practical guide.

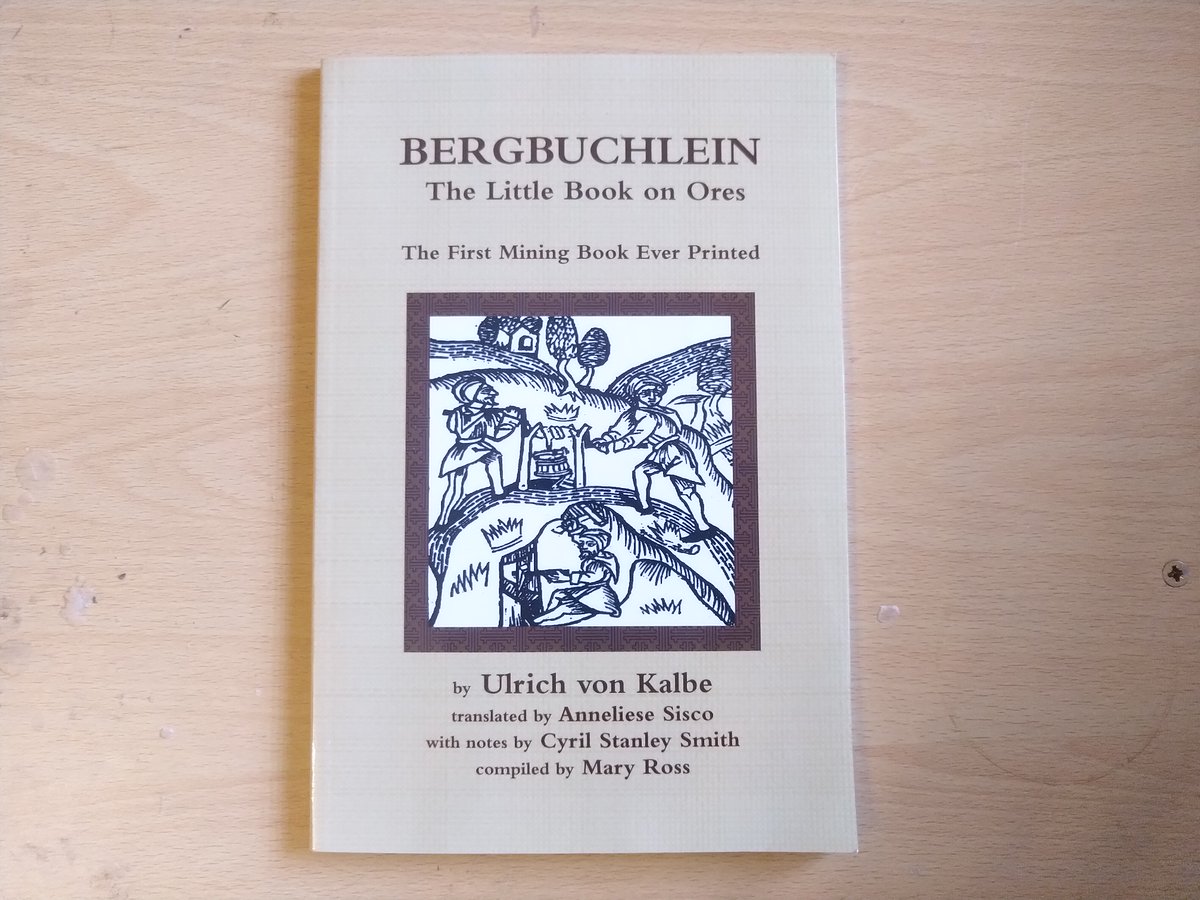

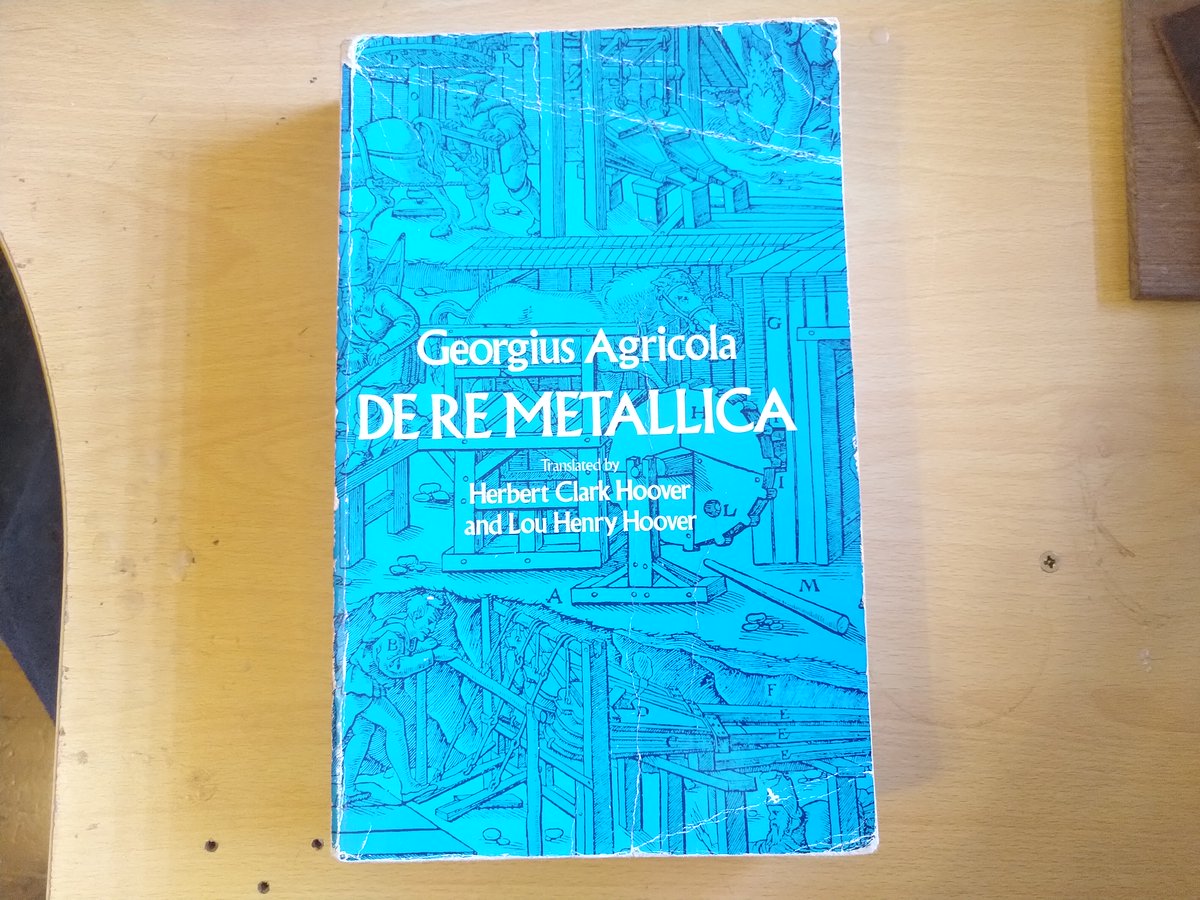

The gap ends with the development of the printing press in Europe. Suddenly...well, it& #39;s hard to say that more books were written, but there were more copies, and therefore more survived. I& #39;m not big into mining, myself, but books like this are helpful.

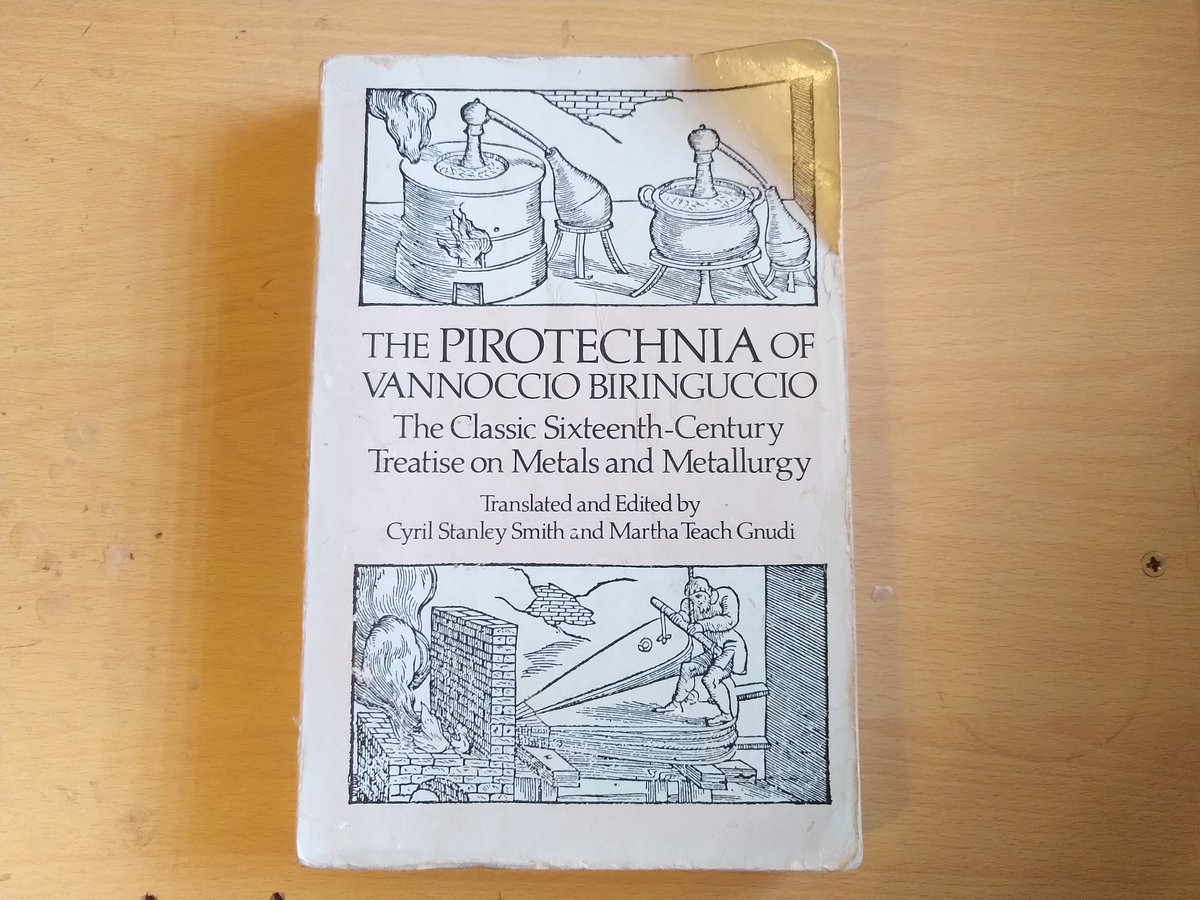

One of my favourites. Biringuccio was a practical man, by his own account. Not a scientist, but an engineer, and a realist, who gently mocked mystical alchemists, preferring experience to theory, and encouraging the reader to do the same. This is mostly about large foundry work.

More on mining, but also lots of pragmatic info about assaying and refining various materials, whether they are metals, or acids. The diagrams are absolutely stunning, and describe the tools, workers, buildings, and the level of technology, in a way that the written word cannot.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter