It& #39;s true: Irvine& #39;s harbour is a little cut off from the rest of the town. Why is this the case? Read on to find out... (1/13) #IrvineNewTown https://twitter.com/Silenceothebams/status/1248178503071215616">https://twitter.com/Silenceot...

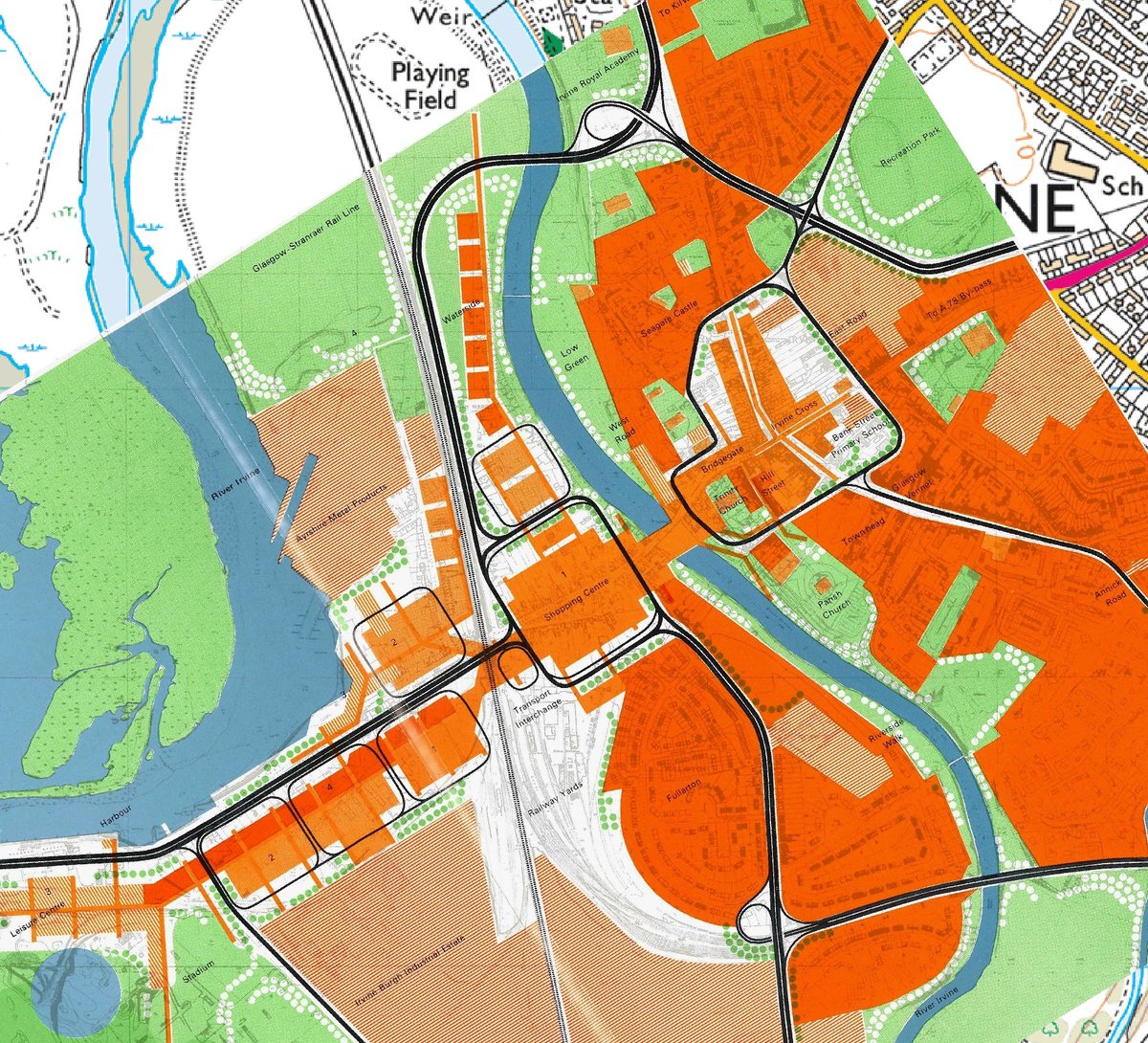

This is Irvine as it appears today. From above, Irvine Development Corporation& #39;s vast megastructure dominates, seemingly landing over the river like a giant spaceship. Ostensibly, this has done nothing to help the harbour& #39;s situation. Why on earth did they put it there? (2/13)

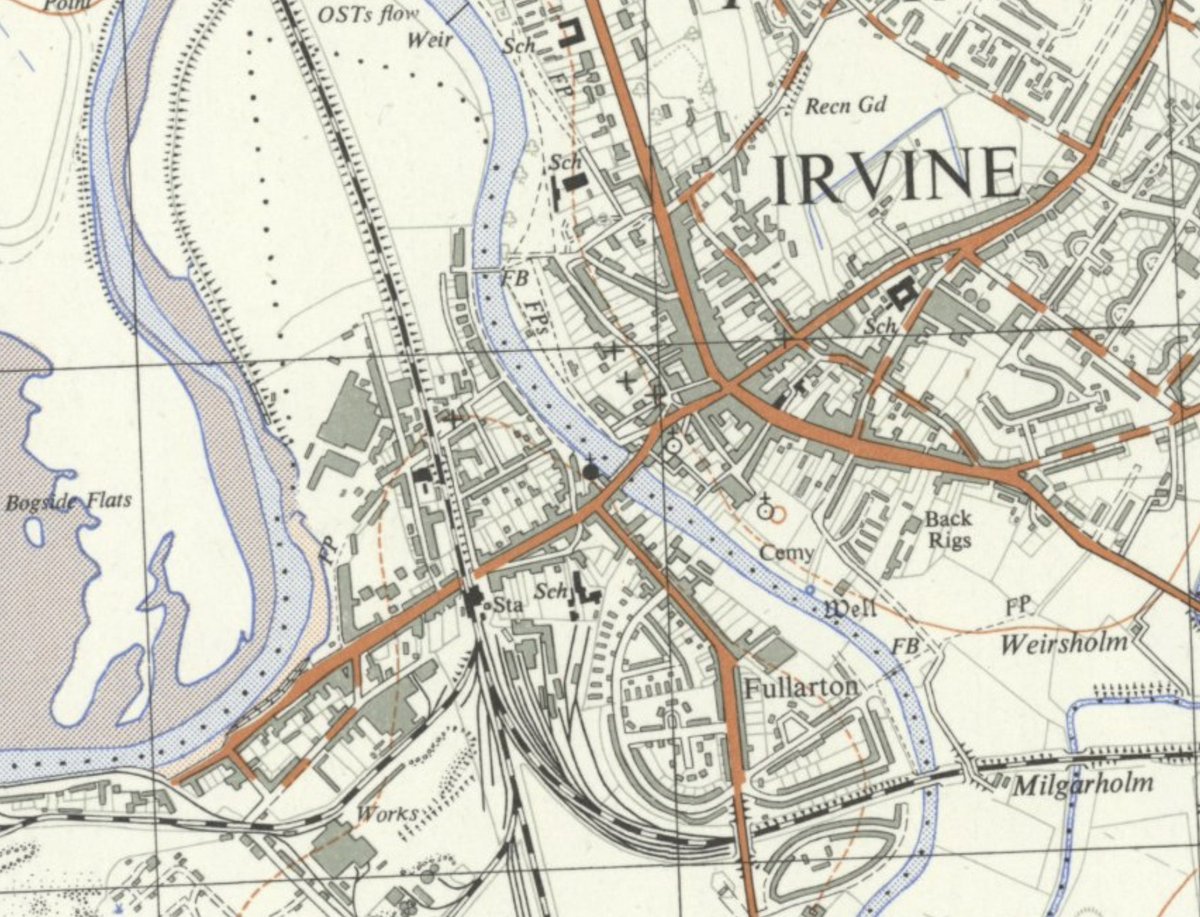

This is Irvine in the late 1950s, around ten years before it was designated a New Town. At this time, the River Irvine was crossed by a bridge built in 1753, subsequently widened in 1827 and 1889. This presented a major problem for IDC... (3/13)

Three major roads in SW Scotland - from Glasgow, Kilmarnock, and Ayr - all converged on a single point: Irvine& #39;s bridge. Barely wide enough for two cars, this resulted in a traffic bottleneck with regional impacts that, by the 1950s, was at a critical level. (4/13)

Irvine& #39;s narrow bridge effectively strangled the harbourside, cutting it off from the rest of the town. The Glasgow-Ayr railway line, on its high embankment, compounded the problem. How would IDC overcome this to make the most of the UK& #39;s only New Town with a seaside? (5/13)

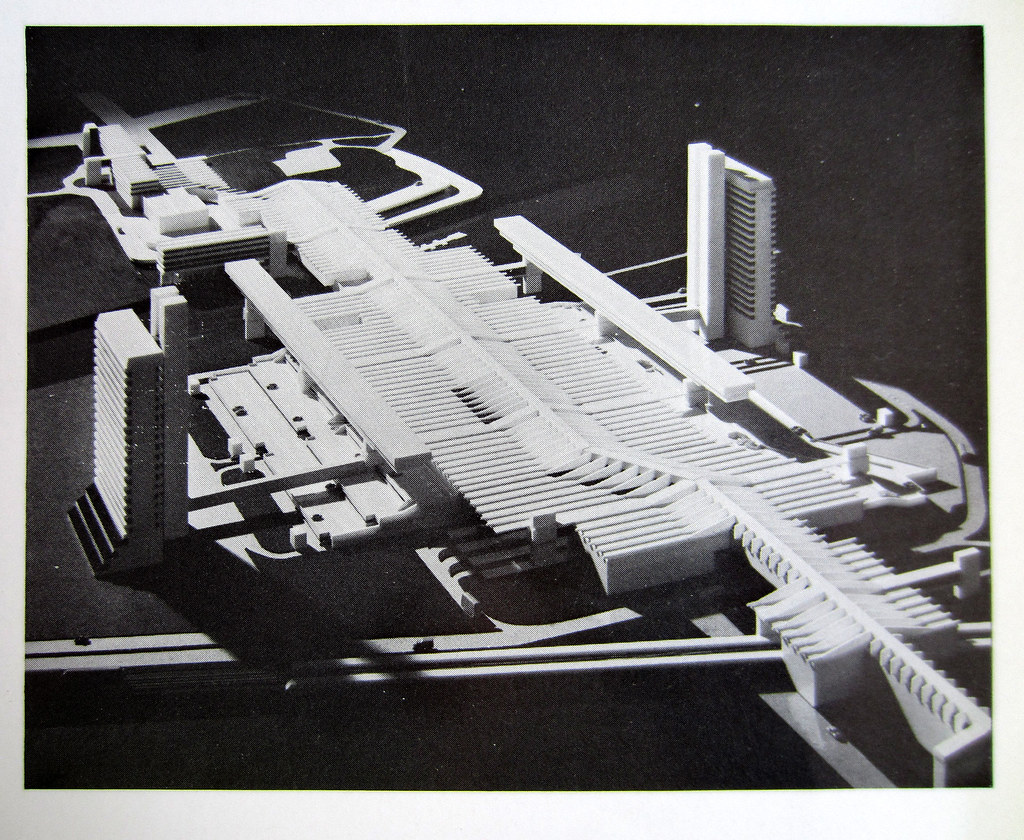

Their solution was colossal yet simple. The bridge would be taken out of the equation and replaced with a modern, pedestrianised equivalent that would contain shops, be fully enclosed, heated, and air conditioned. (6/13)

To the north and south, two dual carriageways would be driven around the town, allowing traffic levels previously unthinkable in Irvine to access the new town centre building and, crucially, the harbourside. This would help promote the growth of the town. (7/13)

The new megastructure was seen as overcoming obstacles: the river, the railway line, and now a road network that would eventually feed several multi-storey car parks - all this meaning the burgh, on the other side of the river, would come out relatively unscathed. (8/13)

It would also mean pedestrians would be able to step onto the platform from a Glasgow train and walk to the old town, without having to climb a flight of stairs, cross a single road, or even be outside. (9/13)

The intention was to have the same in the other direction, with a high-level walkway continuing to the Magnum leisure centre, connecting everything along the way. This would have been a leviathan of a building; a megastructure visible from space. (10/13)

It didn& #39;t happen. IDC had six local authorities to please - an impossible task. With the local government reorganisation of 1975, the newly formed Strathclyde Regional Council turned their attention firmly to Glasgow. Irvine was no longer a priority. (11/13)

And from 1979, New Towns across Britain scrapped for funding from successive Conservative governments. Continuing a high-tech, experimental urban design project for some Scots in southwest Scotland would not have been a priority. (12/13)

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter