What can we learn about pandemics from looking at the history of plant epidemics? This week we’re going to dive down on coffee leaf rust, the most dastardly of coffee diseases. Send us your questions! Then join us Friday for a chat with @stuartmccook, historian of rust. THREAD/

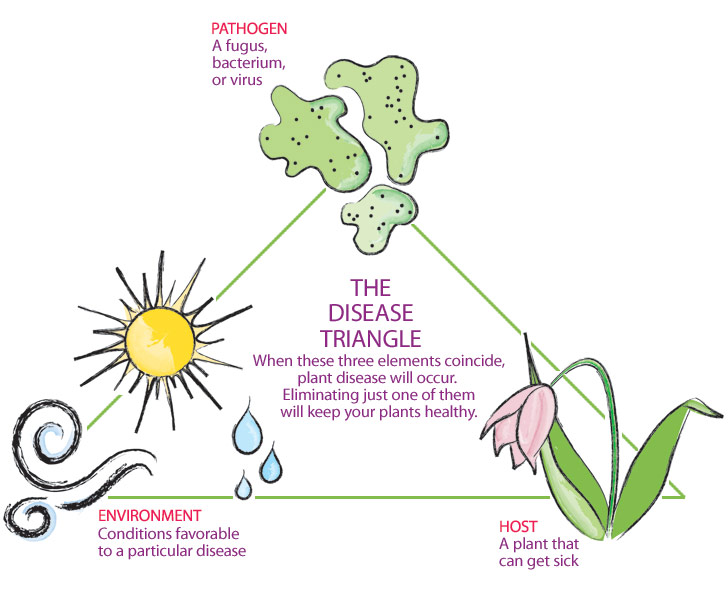

Plant epidemics, like people epidemics, are not created by the disease alone. To become an epidemic you need three things: The disease  https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🦠" title="Microbe" aria-label="Emoji: Microbe">, a susceptible host

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🦠" title="Microbe" aria-label="Emoji: Microbe">, a susceptible host  https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🌱" title="Seedling" aria-label="Emoji: Seedling">, and the right environmental conditions

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🌱" title="Seedling" aria-label="Emoji: Seedling">, and the right environmental conditions  https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🌦" title="Sun behind cloud with rain" aria-label="Emoji: Sun behind cloud with rain"> (i.e., settings that enable the spread of disease).

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🌦" title="Sun behind cloud with rain" aria-label="Emoji: Sun behind cloud with rain"> (i.e., settings that enable the spread of disease).

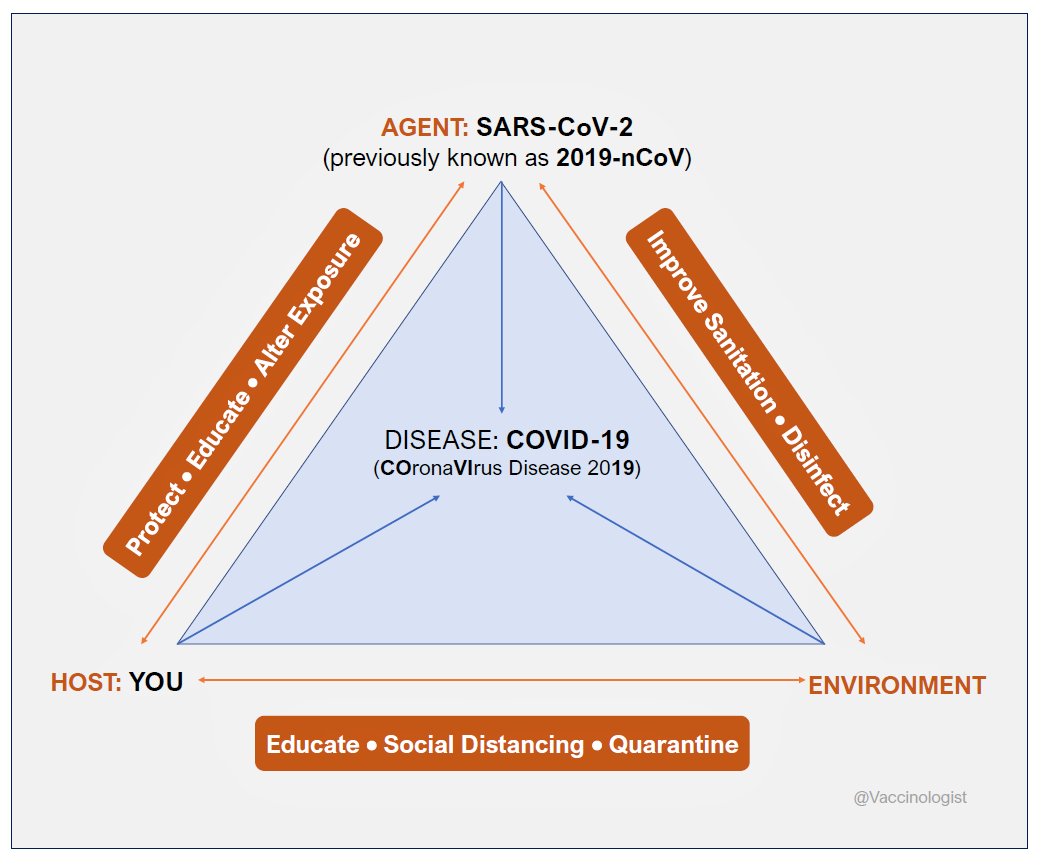

Epidemiologists call it the “epidemiological triangle”; plant disease specialists call it the “disease triangle.”

In the case of Covid19, the disease  https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🦠" title="Microbe" aria-label="Emoji: Microbe"> is highly transmissible, and the host

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🦠" title="Microbe" aria-label="Emoji: Microbe"> is highly transmissible, and the host  https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="👩🏻" title="Woman (light skin tone)" aria-label="Emoji: Woman (light skin tone)"> possess no natural immunity. Environmental conditions

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="👩🏻" title="Woman (light skin tone)" aria-label="Emoji: Woman (light skin tone)"> possess no natural immunity. Environmental conditions  https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🏙" title="Cityscape" aria-label="Emoji: Cityscape"> include a highly mobile, globally connected population and high population densities in cities.

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🏙" title="Cityscape" aria-label="Emoji: Cityscape"> include a highly mobile, globally connected population and high population densities in cities.

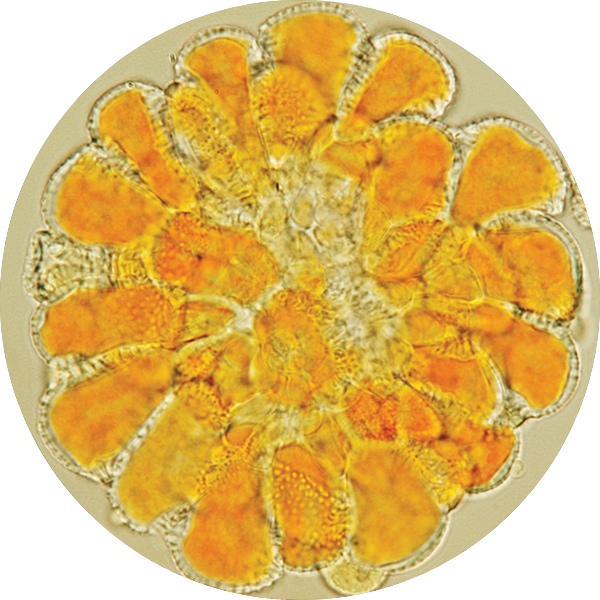

Coffee leaf rust  https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🦠" title="Microbe" aria-label="Emoji: Microbe"> is a fungus, which are the scourges of many crops. Arabica coffee varieties

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🦠" title="Microbe" aria-label="Emoji: Microbe"> is a fungus, which are the scourges of many crops. Arabica coffee varieties  https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🌱" title="Seedling" aria-label="Emoji: Seedling"> have no natural ability to fight coffee leaf rust. Rain

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🌱" title="Seedling" aria-label="Emoji: Seedling"> have no natural ability to fight coffee leaf rust. Rain  https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🌧" title="Cloud with rain" aria-label="Emoji: Cloud with rain"> and wind

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🌧" title="Cloud with rain" aria-label="Emoji: Cloud with rain"> and wind  https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🌬" title="Wind blowing face" aria-label="Emoji: Wind blowing face"> help rust spread.

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🌬" title="Wind blowing face" aria-label="Emoji: Wind blowing face"> help rust spread.

Additional environmental factors that assist the spread of rust include: monocrop plantations (lots of genetically similar, highly susceptible plants all in one place) and poor management leading to unhealthy trees.

But rust can exist on farms at low, non-epidemic levels—even for susceptible varieties—if environmental conditions and farm management help keep the disease in check. In many places and in many years, farmers have mostly figured out how to live with rust.

A fantastic history of how we& #39;ve negotiated living with rust is @stuartmccook& #39;s new book, Coffee Is Not Forever. Add it to your #quarantinereading list for tremendous insight into how rust has shaped coffee production as we know it. #wcrreads https://www.ohioswallow.com/book/Coffee+Is+Not+Forever">https://www.ohioswallow.com/book/Coff...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter