1 When the @V_and_A closed its doors to the public, the exhibition I worked on, Cars: Accelerating the Modern World, also had to close early. Luckily, before we started WFH, I was able to snap several pics.

2 A twitter thread about an exhibition on cars might not be what you’re looking for at the moment. But if you wanted to see the exhibition and couldn’t, or you want some distraction from other news, here is a VERY long thread.

3 Let’s start with the basics: why did the V&A choose to do a show about cars at all? Well, first because we’ve never done one before. We’ve avoided the subject for our entire 168-year history! Why?

4 Because, the car was originally perceived as a piece of technology, not design. What we considered design a century ago was more limited (for instance, it was considered a radical departure when the V&A first collected radios, and that was the 70s).

5 So cars went across the street to our neighbours at the Science Museum. They have an incredible collection, and in fact we borrowed one, the Benz Patent Motorwagen 3 for the exhibition.

6 But as definitions of design expand, the lines between what constitutes design and what constitutes technology are increasingly blurred. The phone or computer you are reading this on, are both highly advanced technologies and thoroughly considered designs.

7 So a car is both a piece of design and a piece of technology. Once you accept that, it’s not a huge leap to consider the car as perhaps the most impactful piece of design of the 20th century. A single design that transformed the planet and our lives.

8 Now, a lot about the car is set to change. A switch to electric, more autonomous driving, ridesharing, and an explosion of mobility alternatives have entered the fold. This is good, as our current system is increasingly untenable.

9 Given these changes, we decided a retrospective was in order, an autopsy on the phenomenon of the car of the past, to see if there were lessons we can draw for the future. Enough preamble though, here is the exhibition.

10. We start with a history of the future, a look at how the automobile was used as a way to dream up utopian futures. A common thread emerges, sci-fi imagines mobility to be fast, fluid, and frictionless - the car has secretly always wanted to fly.

11 Here is our first car. The GM Firebird. It has never been on show in the UK before. It’s the first of four such designs, used in the 1950s to drum up enthusiasm for the cars potential at GMs Motorama shows. (this is where my bad camera pics begin and improper lighting, sorry!)

12 The car takes obvious cues from jet fighter planes used in World War 2. It has a cockpit, a wing-like silhouette, and yes, a jet engine in the back. It was generously borrowed from the GM Heritage Center.

13 Above is a film made for Firebird II (look closely and you’ll spot our first Firebird in the background). A family frustrated by traffic jams is transported to 1973 to enjoy the ‘Safety Auto Highway’.

14 It’s an early attempt at imagining autonomous driving (with radio technology and control towers). A reminder that a lot of ideas we think as new have been cooking for a while. You can watch the full film here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rx6keHpeYak&t=12s">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

15 In the next room we follow the theme of the future. We played with the idea of a typical salon hang, but instead of paintings, we brought together imagery of future cars from across the world, and over the span of a century.

16 Here’s work from illustrator François Schuiten published in ‘Encyclopédie des Transports Présents et à Venir’ (1988), a bit of a steampunk mashup of old forms meeting new purposes.

17 Here’s a hand-coloured print from 1902 by Albert Robida called ‘La Sortie de l’opéra en l’an 2000’ depicting all sorts of flying vehicles as people leave the opera. Women are seen driving their own vehicles, a promise of new liberties in vehicular-form.

18 A movie I had never seen before, Just Imagine (1930), looks at New York City in the 1980s, with bustling flying thoroughfares, and a couple flirting with each other between two vehicles. You can see the clip here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sroujzPNM40">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

19 And heck, now that you might have some time on your hands, you can watch the whole movie here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u3pkn2ejmNo">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

20 Here’s another rendering of a future New York, artwork by Patrice Garcia for The Fifth Element (1997). The flying cars are still here, but it’s a grittier vision of the future. The updated checker cab is a nice touch.

21 These drawings (1924) are by Ferdinand Fissi, John Scott Montagu’s illustrator for The Car Illustrated. Lord Montagu was an early advocate for motorways in Britain, and here they are imagined built into the architecture of the city.

22 In 1928, the Russian Constructivist Georgy Krutikov imagined entire floating cities of the future. Here, he designs a streamlined capsule and recliner chair to move around these new urban spaces. (one of the prettiest drawings in the show imho)

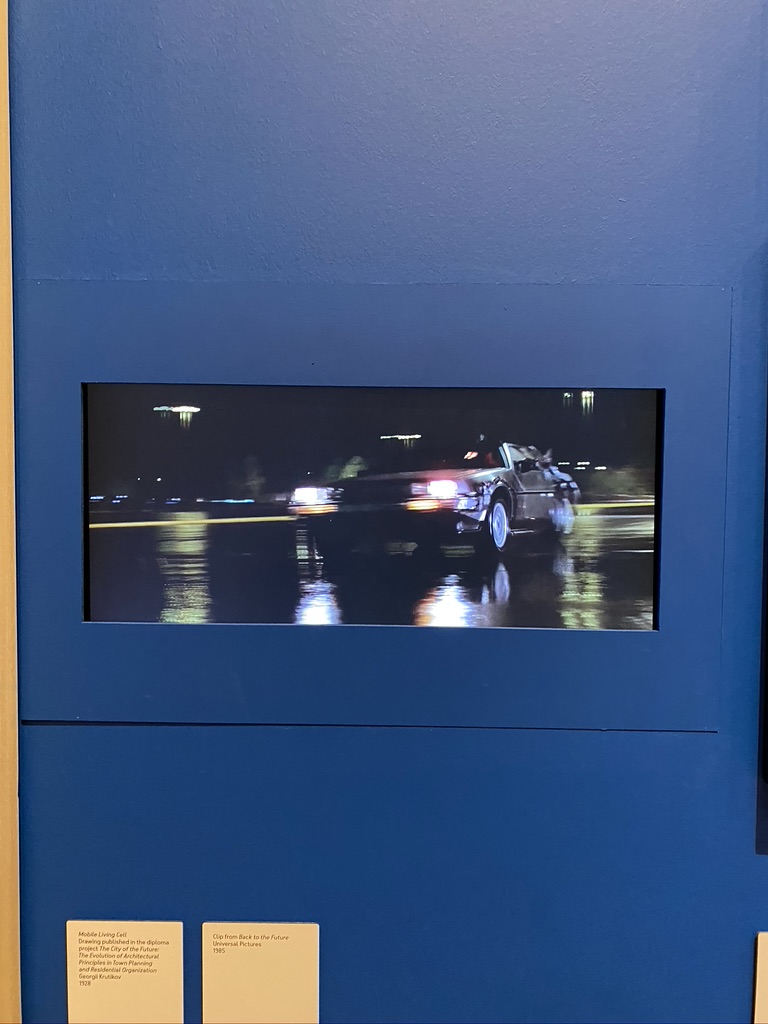

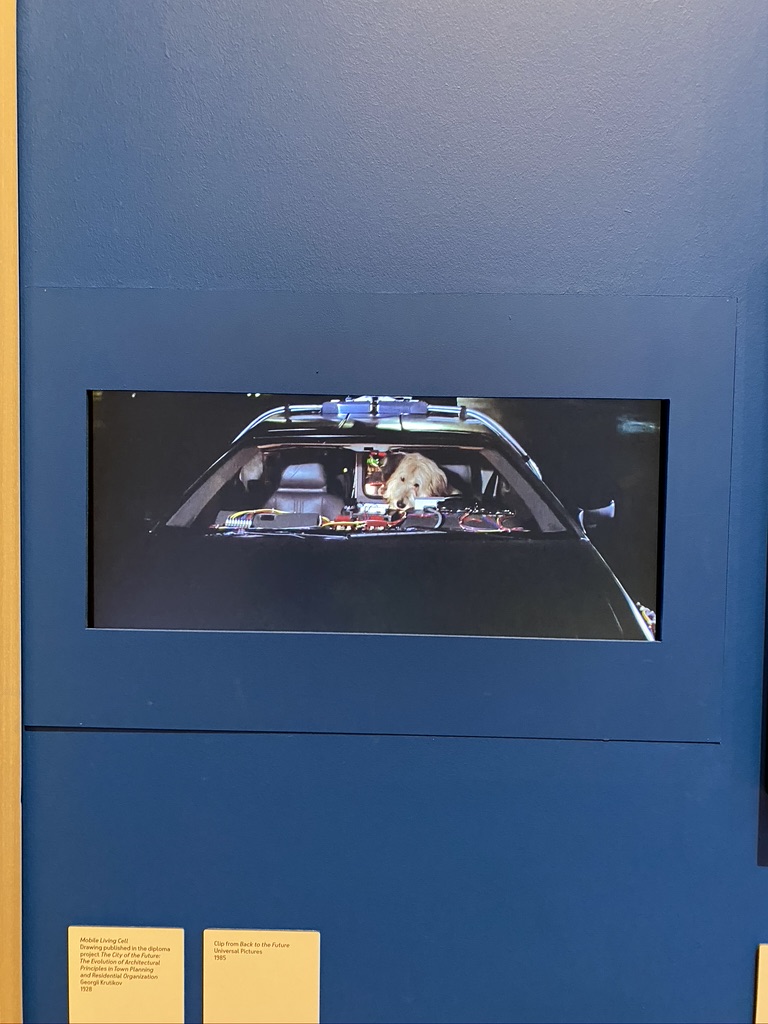

23 The Delorean may have been a failed commercial venture, but it was given new life as the star of the Back to the Future (1985). The car as a proposal to travel through not just three dimensions, but four.

24 Magazines also sponsored competitions to imagine new types of mobility. Here is one of my favourites, the ‘World Transportation Invention Competition’ in Shōnen Club (Boys Club) in 1936. The illustration is by Iizuka Reiji.

25 Speaking of competitions, here are submissions to the Fisher Body Craftsman’s Guild’s national model building competition (1930-68). Many teenagers would submit designs, with winners being offered jobs at General Motors.

26 One winner was Pete Wozena; after winning in 1939 he got a job at GM working for their Pontiac division. Here is another future car concept that he drew later in his career in 1961.

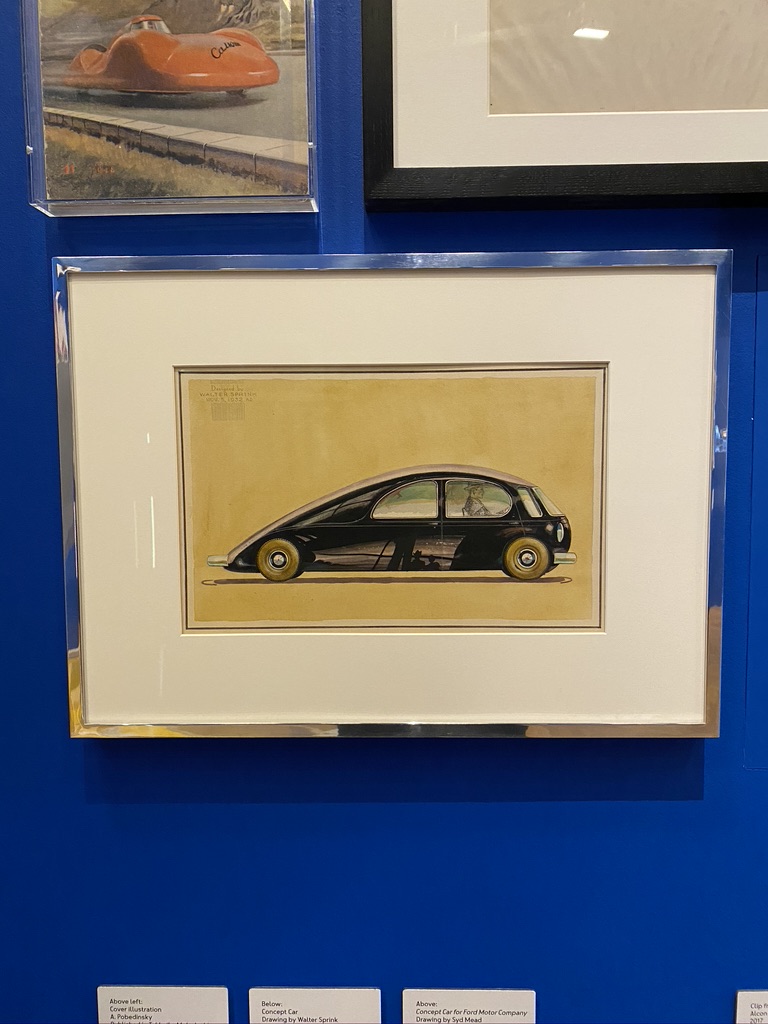

27 The commercial artist Walter Sprink designed this concept car in 1932. He was based in Akron, Ohio, and if the car resembles the silhouette of an airship that’s no coincidence, Akron was home to the Goodyear Zeppelin Company.

28 Norman Bel Geddes also championed the ‘streamlined’ aesthetic to suggest an image of the future. Here are a few of the hundreds of model cars used to populate his Futurama pavilion for GM at the 1939 World Fair.

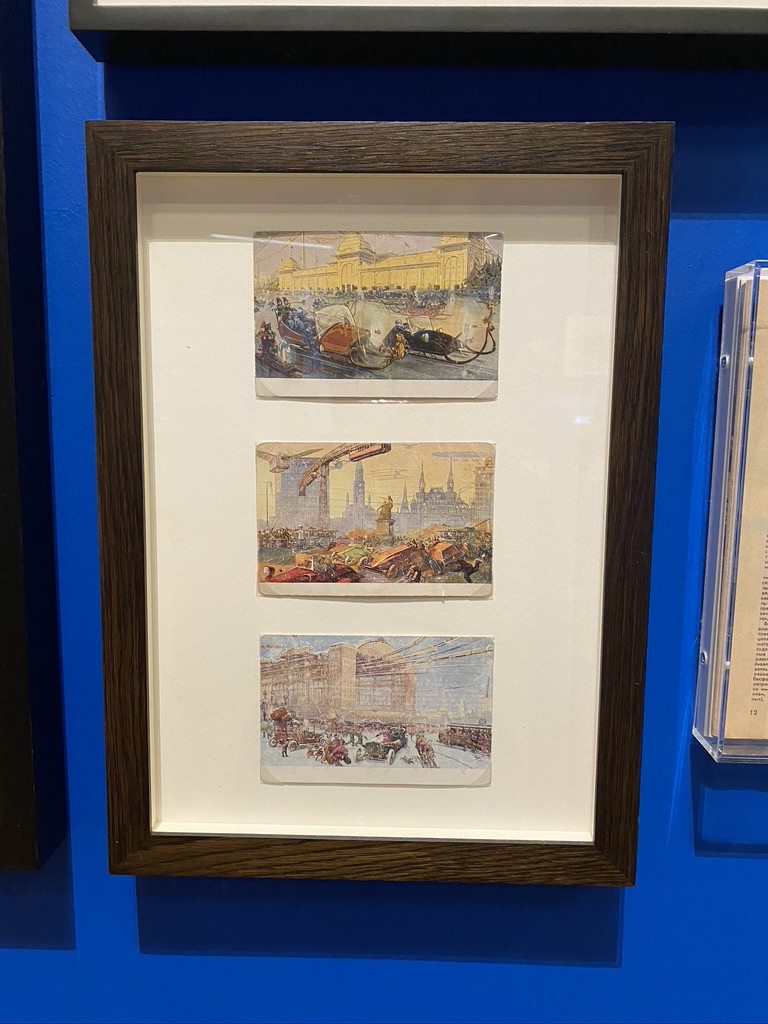

29 One of the more surprising finds in our research was this set of postcards from 1914 depicting Moscow in 2259; a confluence of suspended trams, dirigibles, and motorized sleds.

30 Here’s some social distancing avant-la-lettre, Walter Molino’s cover for Domenica del Corriere in 1962. The opposite cover features a scene of a traffic jam and road rage, and this was the provocative solution.

31 And finally, we have this gorgeous drawing from the incomparable science fiction (and very real) designer Syd Mead, ‘Concept Car for Ford Motor Company’ (1959). Mead sadly passed away earlier this year.

32 One thing I’m really happy with is our collaboration with @Masters_Alice to produce immersive film work for the exhibition. So much of the experience of cars is wrapped up in movement and sound, and so we knew film would play an important part.

Here our designers @officemmx created this multi-screen projection space, for Alice to create a montage of the city from the vantage point of the automobile accelerating through the course of a day.

34 Bonus points if you can identify which film score our sound designers @codatocoda reference in the two-chord motif for this piece.

35 In the next section, ‘Going Fast’ we take a closer look at what really drove the initial appeal of the automobile. Far from being a practical tool for getting around, it was the unique thrill of racing which drove early sales.

36 Here is the Benz Patent Motorwagen 3 (1888). The Motorwagen is widely regarded as the first ever production automobile. It couldn’t go terribly fast though, around 10mph. By comparison, trains of the time could go much faster.

37 So what was the appeal? With the automobile, speed was in the hands of the individual driver, and racing became a test of your skills and knowledge. Quite quickly, city-to-city races started to crop up, the first in 1895 from Paris to Bordeaux. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paris–Bordeaux–Paris">https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pari...

Alright here& #39;s some insider info, a car that we wanted but couldn& #39;t get in the show. This is the first car to go 100km/h, in 1899 (also electric). It& #39;s called the Jamais Contente (never satisfied) a perfect metaphor for racing.

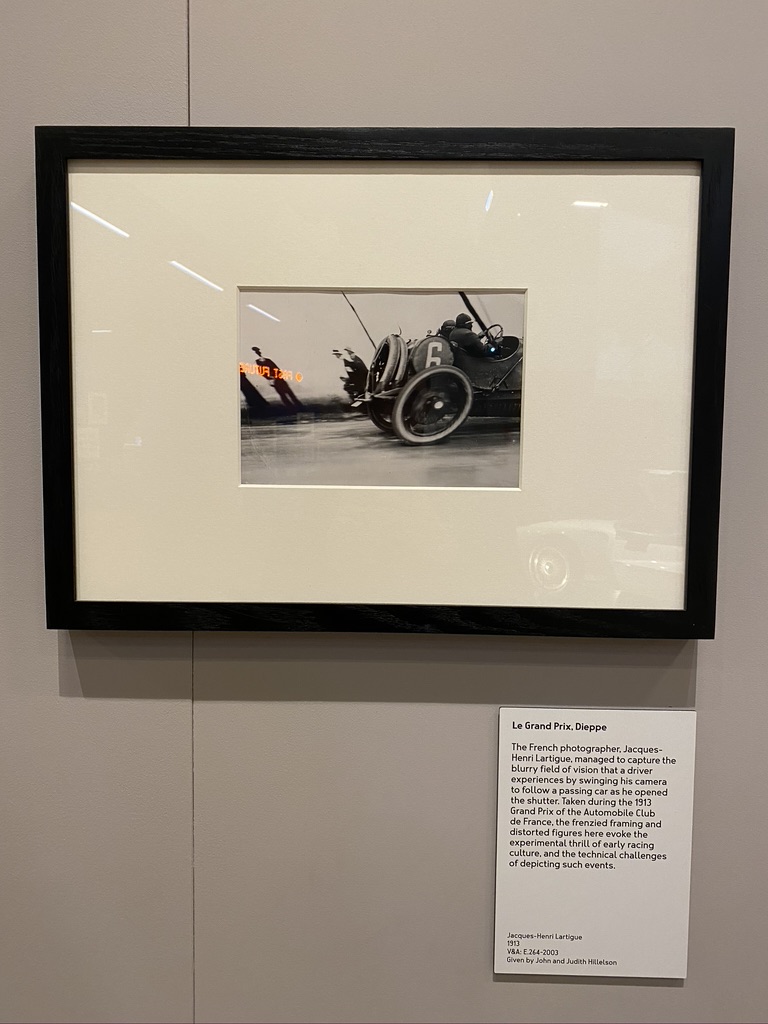

38 Here’s a photograph by Jacques Henri Lartigue which he snapped as a teenager at the Grand Prix in Dieppe (1913). To capture the fast-moving car, he swivels his camera, creating a remarkable distortion effect, capturing the excitement of such events.

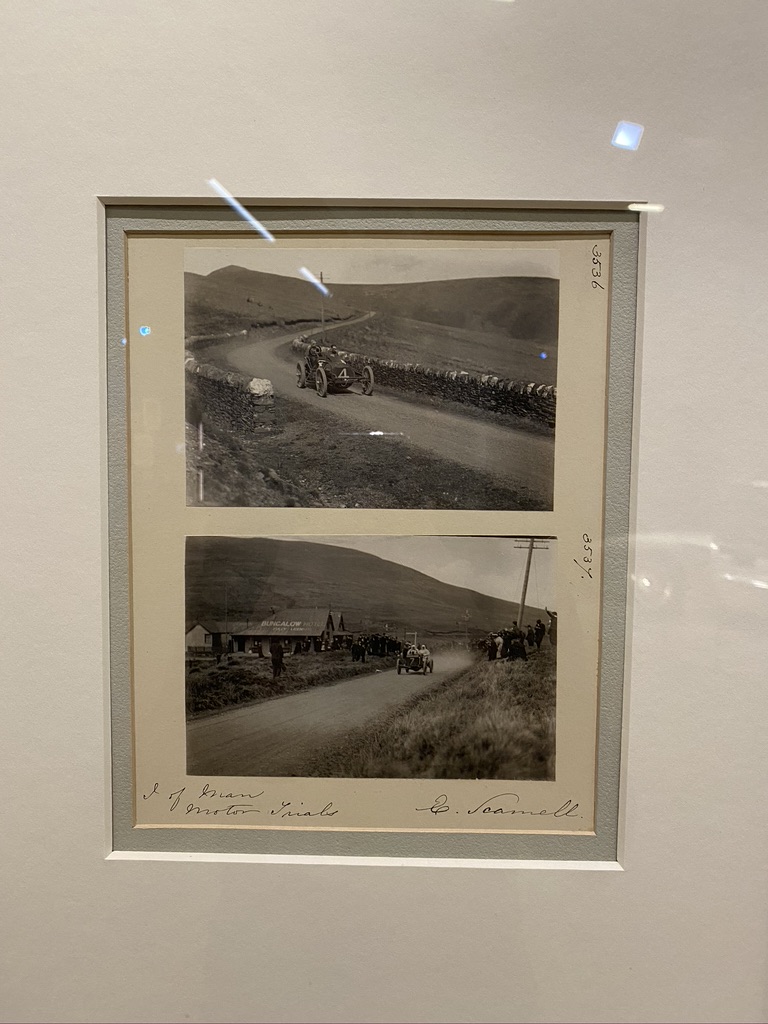

39 And here are photographs from the speed trial for the Gordon Bennett Cup on the Isle of Man. Why were they held there? Because, the British, fearing public safety, issued a universal speed limit of 20mph on all roads in 1903. Racing moved elsewhere.

40 You can also see film of the trials here (1904). One gets a sense of the absolute precarity and danger of these new-fangled inventions as they manoeuvred

hairpin turns and rough roads. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tRvOhL_rR9U">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

hairpin turns and rough roads. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tRvOhL_rR9U">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

41 These were as much social affairs as they were trials of skill. Andrew Pitcairn-Knowles focused his lens on the bourgeois society who gathered in Ostend, Belgium, in part to show off their fabulous wheels in 1908.

42 Governments were quick to champion homegrown technical achievements. Here’s an Empire Marketing Board poster flaunting various UK-held speed records, including the Golden Arrow’s, set in Daytona in 1929. & #39;Britain First Always& #39; sounds awfully familiar...

43 Henry Segrave drove the Golden Arrow down a strip of Daytona Beach reaching a top speed of 231.45 mph. Part of the spectacle was down to the Golden Arrow’s unusual streamlined shape. You can see it here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VoG4fgAk9S0&t=592s">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

44 Similarly, by the late 1930s the French government was keen to take back titles of the Grand Prix after years of domination by the Germans. They sponsored a race with a million franc prize for anyone who could design a car fast enough.

45 This was the winner, the Delahaye 145 driven by René Dreyfuss. The trick worked, and not only did Delahaye get the million francs, but the car - driven by Dreyfuss - went on to win the 1938 Pau Grand Prix.

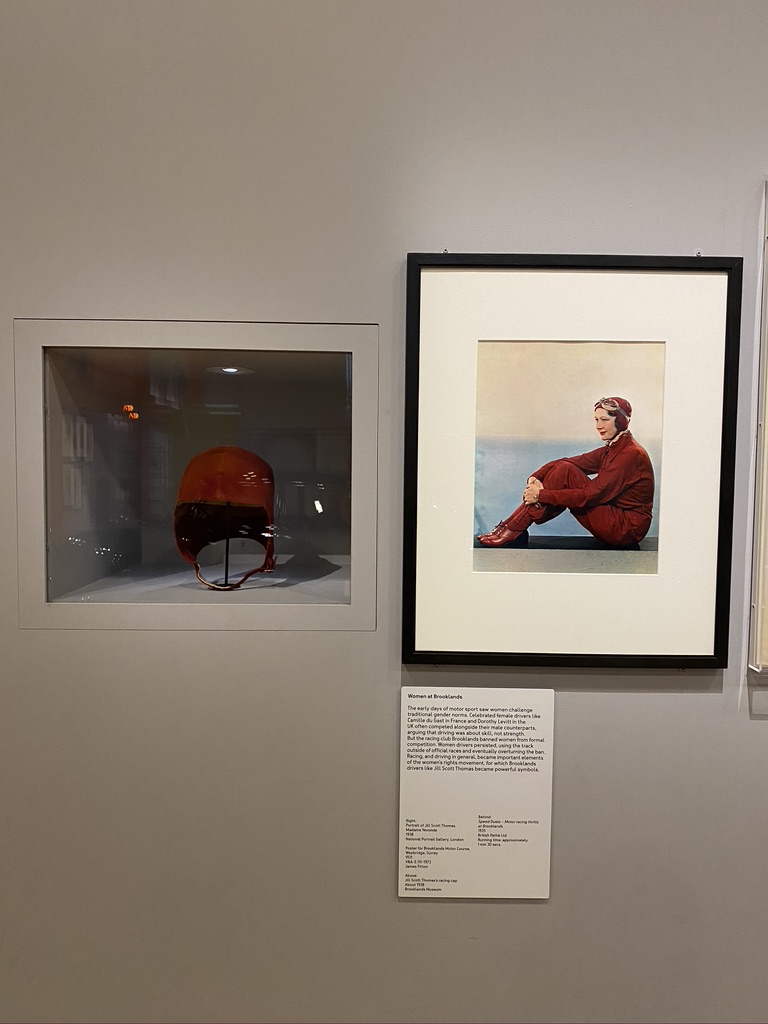

46 Meanwhile, back in Britain, to get around the 20mph speed limit, the world’s first-ever private motorcar racetrack was invented in 1907, called Brooklands. It became the epicentre for UK race culture for several decades.

47 Brooklands often held regular ‘ladies’ races’. Earlier, men and women would race in the same races. The success of women drivers helped immensely in building an image of empowerment and the notion of the car as a liberating tool. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_KPBWYKDRjU">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

48 Here we were able to find driver Jill Scott Thomas’ portrait at the NPG and her bonnet at Brooklands Museum, and reunite them here for this show. (This is a very satisfying feeling - the ASMR of curating)

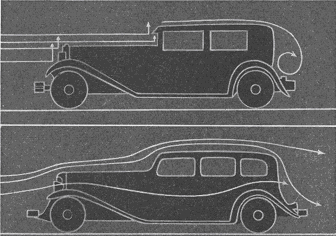

49 While a lot of the technology improving a car& #39;s performance took place under the hood, streamlining – reducing air resistance through form - proposed a dramatic new look to the car’s outer body.

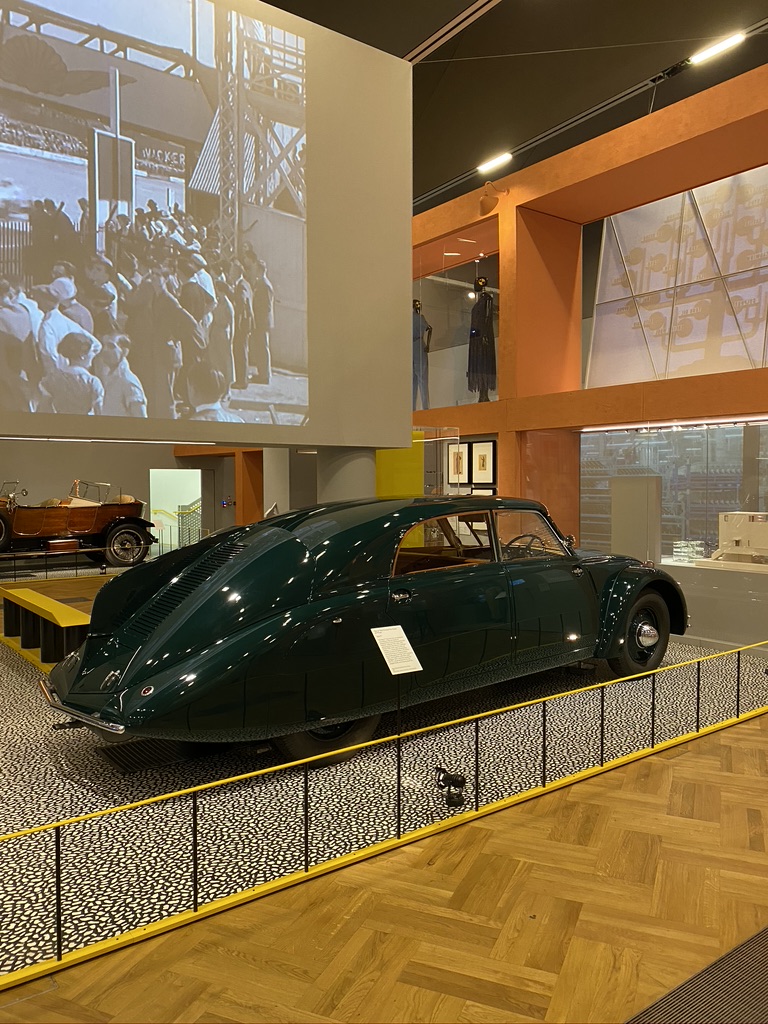

50 Streamlining in cars was pioneered by Paul Jaray, who in the 1910s worked on streamlining zeppelins. In the 20s, he devoted himself to advocating for streamlined cars, eventually working with Hans Ledwinka on the Tatra 77 (1934).

51 Other companies quickly followed, realizing there was a buck to be made on selling this new look/technology. Here’s ‘Streamlines’ (1936) from Chevrolet Motor Company for instance: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tsvkSmtFDzs&t=346s">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

52 Meanwhile the notion of increased performance through streamlined shapes also affected clothing. In the 1920s, an increased interest in athletic leisure gave rise to a new body-hugging silhouette, as seen here in a swimsuit, flight suit, and ski outfit of the era.

53 This is one of my favourite images in all of 20th century design history – Raymond Loewy’s Evolution of Design chart. In it, he positions the streamlining aesthetic in Darwinian terms, as a natural progression for all things.

54 So what began as a technology for increasing speed and efficiency, gets picked up by designers and used as an aesthetic that symbolizes progress and the future. Does a meat slicer ever need to go fast? No, but it certainly looks cool.

55 But if so far, the enthusiasm for automobiles has been wrapped up in their ability to go ever faster, how did we confront the fact that they were also killing machines? The invention of the car was also the invention of the car crash.

56 At first, the reaction was to blame the driver, not the car. Public safety campaigns like these from the UK focused on educating drivers with better driving practices. This has remained a theme in most safety campaigns today.

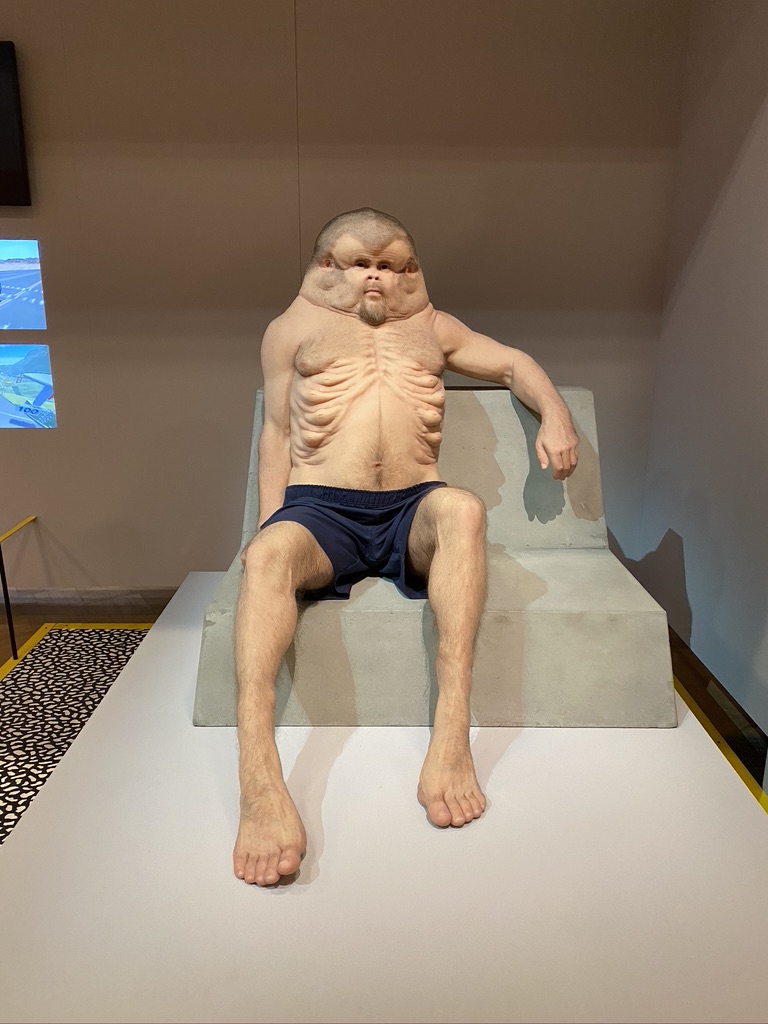

57 The Australian TAC are infamous for their sensational ads, urging drivers against DUI and not to speed. Here they commissioned Patricia Piccinini to create Graham, a projection of what a human being might look like if they were to evolve to naturally survive car crashes.

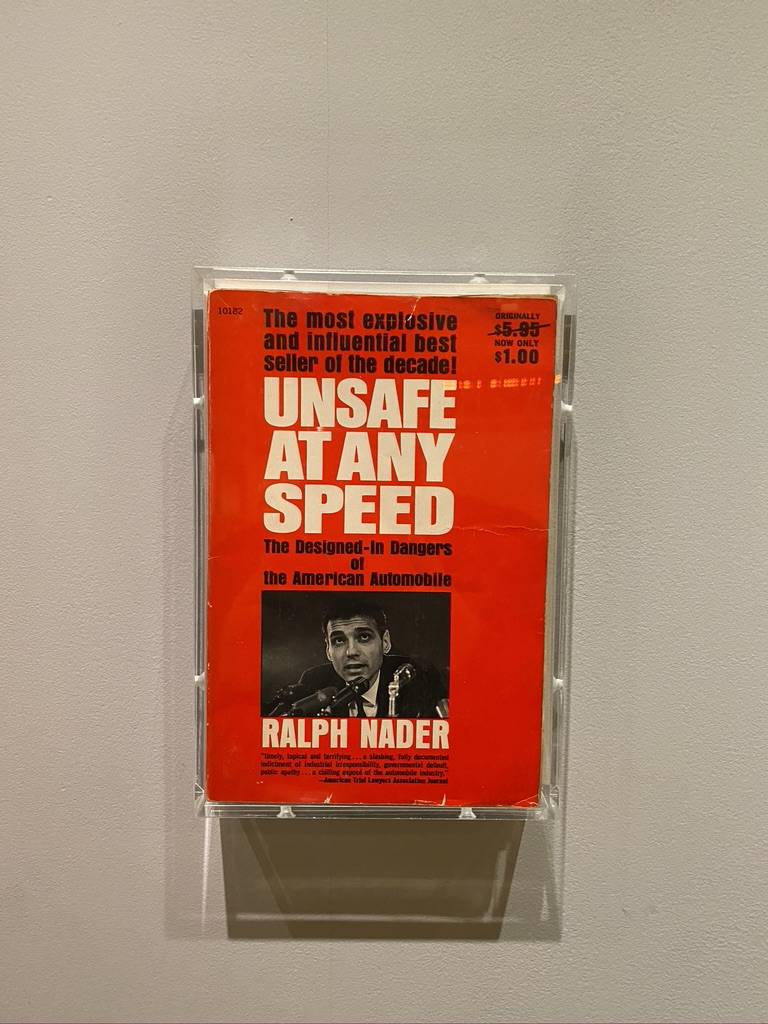

58 But what about designing safer cars? This is what Ralph Nader (remember him?) pushed for in his landmark exposé ‘Unsafe at Any Speed’ (1965). In it, he points the blame at large car makers for designing cheap flimsy cars the put lives at risk.

59 Part of the problem was the rise in popularity of the muscle car in the mid-60s, putting overpowered engines into lightweight vehicles, which caused a spike in automobile deaths. Here’s a Ford Mustang, which along with the Pontiac GTO, pioneered the new style.

60 Hollywood matched this trend with a new style of movie, in which a brooding male (anti)-hero kicked up a lot of dust in their muscle car of choice. A case in point, the famous chase scene with Steve McQueen in Bullitt. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=31JgMAHVeg0">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

61 In response to Nader’s book, the US government began to legislate for more safety standards in cars. In 1973, they prompted car makers to produce ‘experimental safety vehicles’. Here is GM’s design, with an unusual back seat padded dashboard.

62 Of course, there’s an entire history to be told about the design of safety in cars. We gathered a few of them here. From car horns, headlamps, windshield wipers, seatbelts, collapsible steering wheels to ABS brakes.

63 Death rates may have gone down, but still 1.25 million road fatalities occur a year. The car is the only piece of design that we accept as a daily necessity despite the number of fatalities it produces. Would you take a plane if a similar death rate existed?

64 On a lighter note, there is a whole digital world now where people are getting the thrill of speed without the danger. These videos were produced by users of BeamNG Drive, a simulator which allows people to invent their own stunt and crash scenarios. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h93Yn1ZoRjw">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

65 If speed was the original value proposition of the automobile, the next riddle to unravel was how to take a complex expensive machine and make it cheap and producible for the masses. Welcome to the middle section of our show, ‘Making More’.

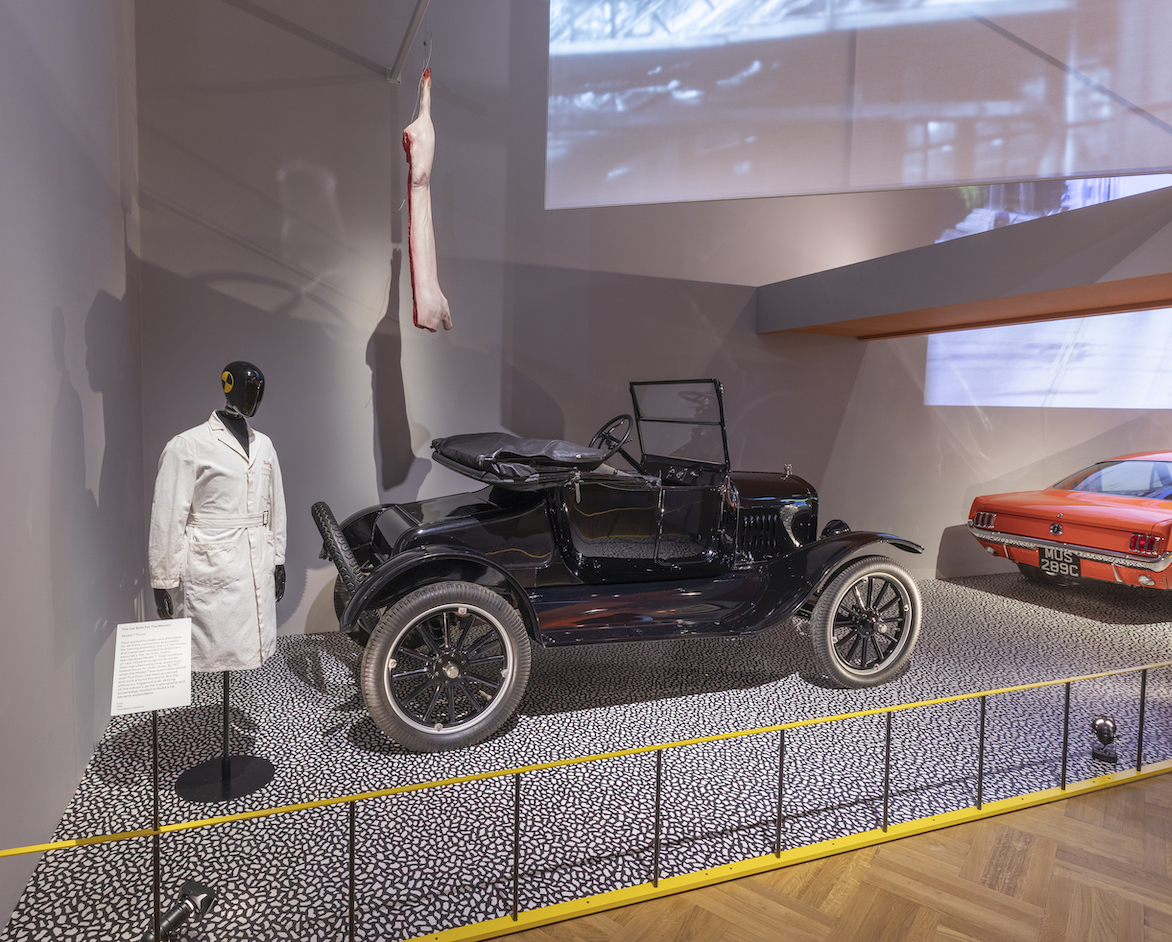

66 The story of Henry Ford, the Model T, and the moving assembly is well-known, but it deserves to be told again here, because its importance transcends so much more than the world of automobiles.

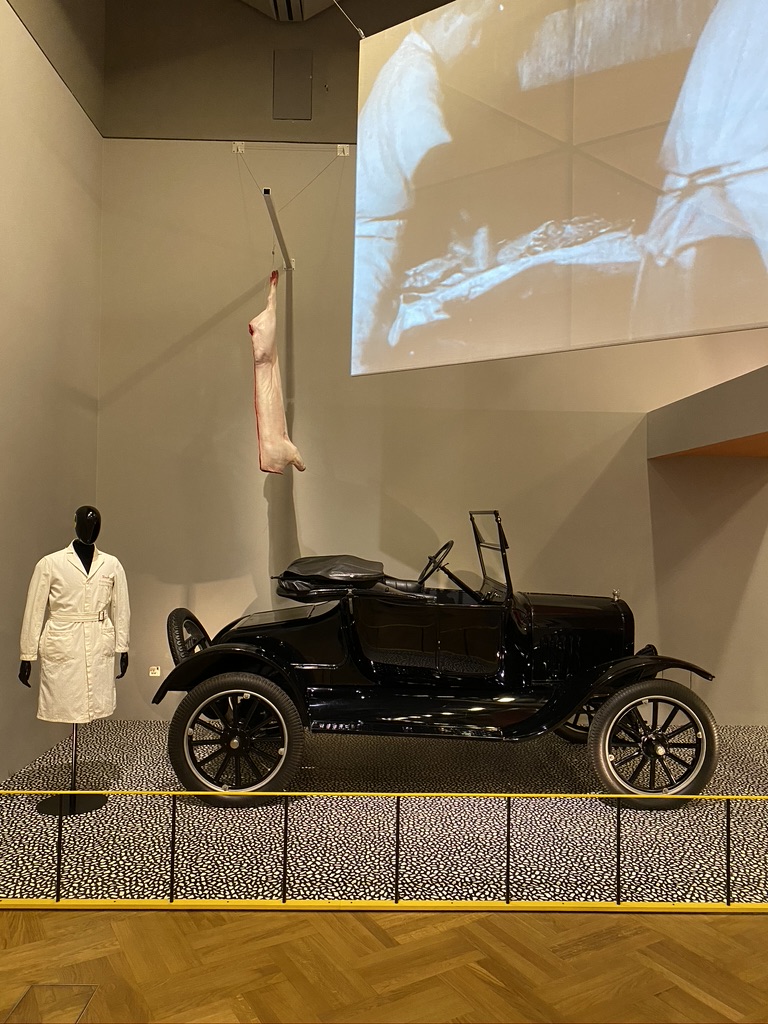

67 For starters, why is there a pig carcass hanging here? Because Ford’s main inspiration for the idea of a moving assembly line came from the slaughterhouses spread across the Midwest. A reminder that innovation is rooted in time and place.

68 Ford made this film of a slaughterhouse in Cincinnati to see how animals came in whole, moved through the building, and were ‘disassembled’ into their various parts. Ford simply reversed that process: from disassembly line to assembly line. https://www.shutterstock.com/video/clip-4078396-1910s---meat-packing-plant-1919">https://www.shutterstock.com/video/cli...

69 And here’s a film of the moving assembly line, implemented at his Highland Park plant in 1913, it dramatically increased the numbers of cars produced while dropping the prices, enabling the Model T to become the most produced car in the world. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pf8d4NE8XPw">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

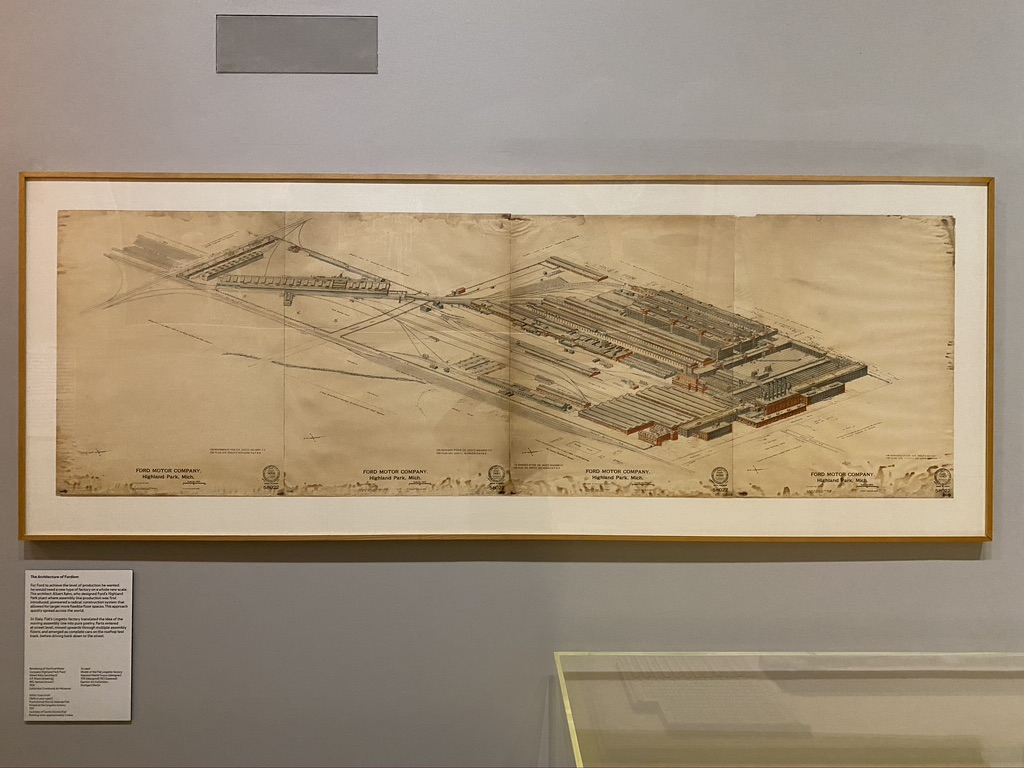

70 Once you can start producing at higher levels of output, you need a whole new type of factory architecture to produce it. Here is a drawing of Highland Park, designed by Albert Kahn, where the moving assembly line was introduced.

71 Based in Detroit, Albert Kahn became the most prolific architect of the 20th century as a he built a specialty in factory architecture. Cheap, efficient, with flexible floorplans, Kahn’s designs were implemented across America and even as far flung as Russia.

72 With the success of mass-produced automobiles, Detroit became a global symbol of industrial power. This mural entitled ‘Automotive Industry’ (1940) by Marvin Beerbohm reflects that optimistic spirit, commissioned by Roosevelt’s WPA program.

73 Key to the global impact of Detroit was that Ford was not shy about showing off his innovations. He opened up his factory to the public for tours, so that they too could witness the spectacle of mass production.

74 Soon, you saw European designers, architects, and entrepreneurs making pilgrimages to Detroit to learn the lessons of mass production and transplant them to European soil.

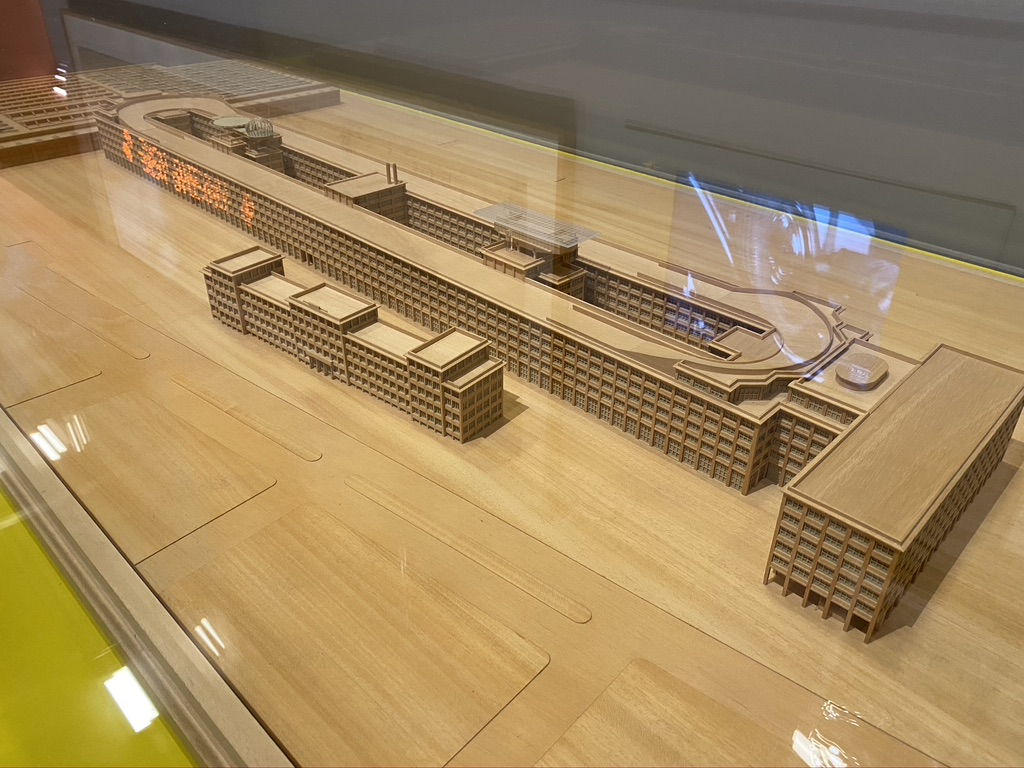

75 Fiat took particular interest. The company commissioned Giacomo Mattè-Trucco in 1919 to build a new factory on the edge of Turin: Lingotto. It remains one of the most poetic translations of Fordism into architecture ever built.

76 Parts enter at the ground floor. Gradually the assembly line moves the car up the floors as it becomes fully realised. It emerges whole on the roof where it is taken for a dizzying spin on the rooftop track. Here’s a fun promo film: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OEwOKNpntsw">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

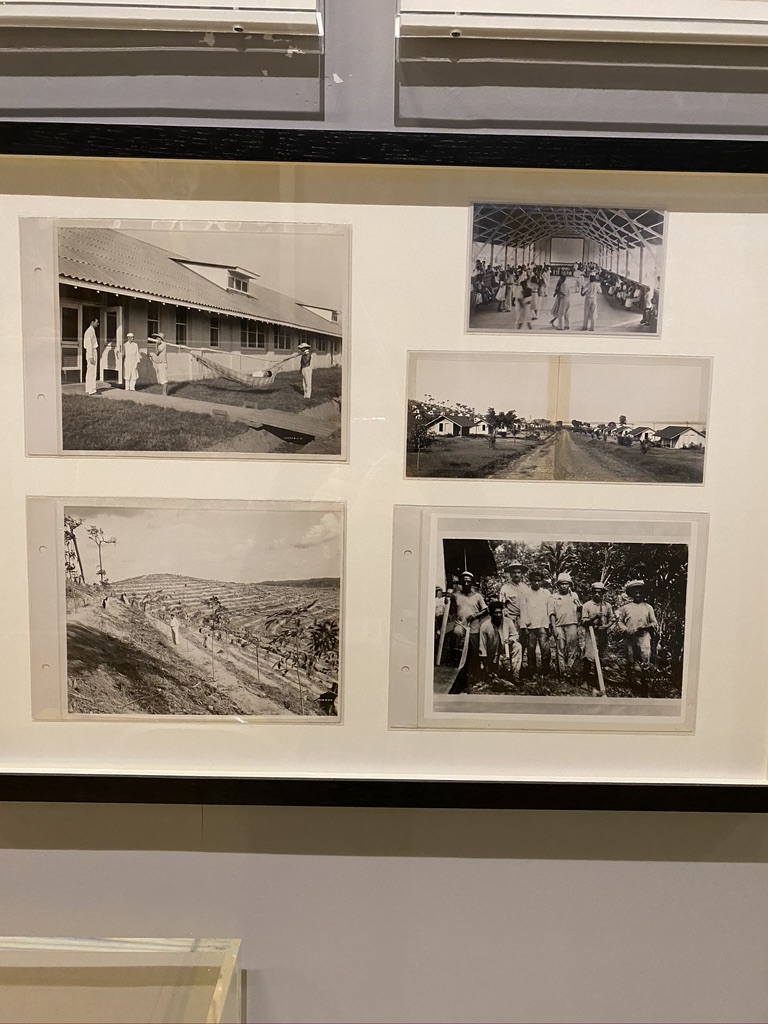

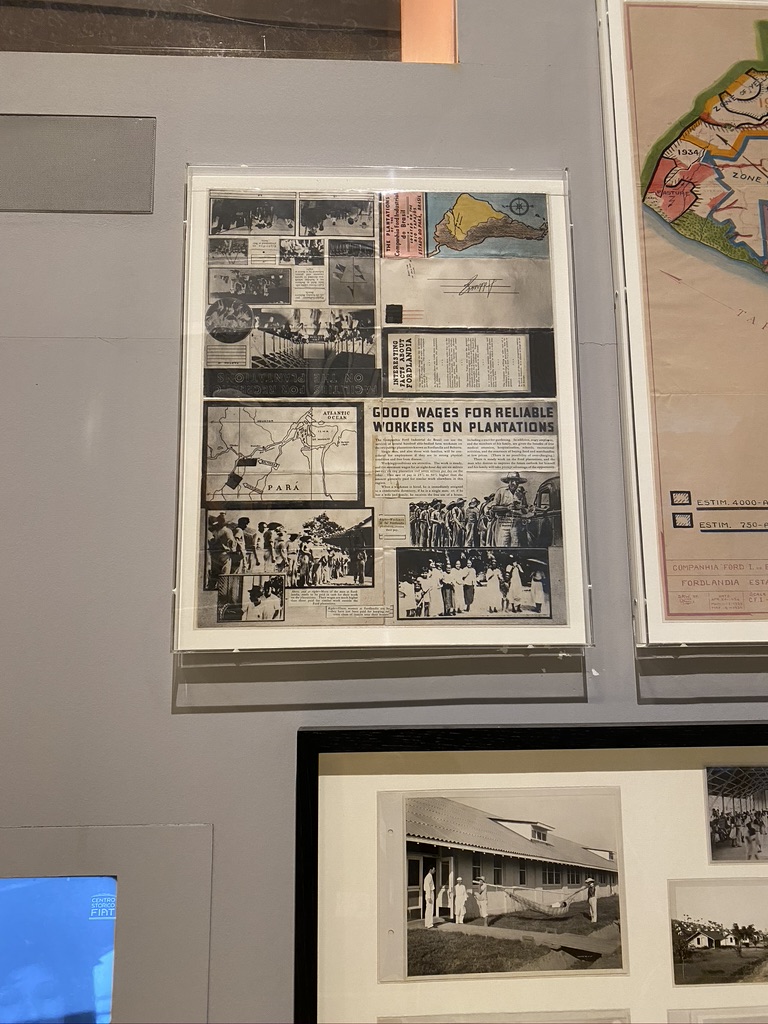

77 It wasn’t just factories that Ford restructured though, he was also meticulous with his supply chains. To get cheaper rubber, and avoid a monopoly held by the British at the time, in 1926 Ford bought a piece of the Amazon the size of Northern Ireland.

78 What did he call it? Fordlandia of course. He set stringent guidelines for his workers. Alcohol, women, tobacco and even football were forbidden. American food served in the canteen. After many worker revolts and difficulties in production, the project was abandoned in 1934.

79 Ford was proud of the complex supply chains the company was able to harness. They celebrate this in their film Ford Symphony in F (1940) You can watch it here, replete with stop-motion figurines. Rihanna eat your heart out. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W7IvQ2tziek">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

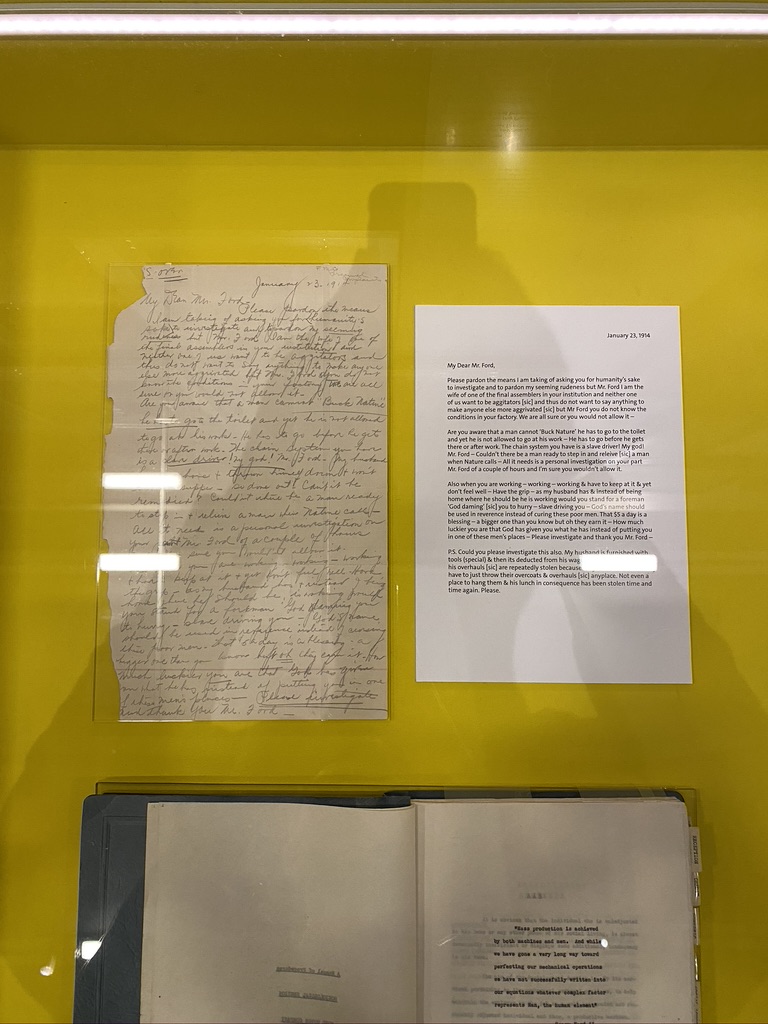

80 The other big challenge Ford faced was how to manage the huge increase in workers needed. The moving assembly line meant you could hire relatively unskilled workers as tasks were simple. The downside is that work was physically and psychologically draining.

81 Here’s a letter from the wife of an assembly line worker in 1914 pleading to Ford about how the new system has broken her husband. You can see a scan of it here: #slide=gs-189056">https://www.thehenryford.org/collections-and-research/digital-collections/artifact/75234 #slide=gs-189056">https://www.thehenryford.org/collectio...

82 To incentivize workers, Ford introduce a $5 a day wage (double what other carmakers were paying). But to qualify, his Sociological Department conducted home inspections to ascertain if workers were following the strict morale code they set out.

83 The economic impact of Ford’s assembly is evident, but the cultural impact is all the more surprising. The public fascination with mass coordinated movement and production led to all sorts of eclectic outputs. The Rockettes, for example! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TtYRS4v2Nec">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

84 The Swiss modern architect Le Corbusier was an avid driver, and with his Maison Citrohan (1922), he calls for all housing to be designed and built in the same way cars are. Mass-produced and affordable for everyone.

85 Walter Gropius, founder of the Bauhaus, cites Ford’s River Rouge plant as one of the most beautiful buildings in America. His school would go on the champion a machine aesthetic and mass-producible designs (which often weren’t very mass-producible).

86 Meanwhile, Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, working on social housing in Frankfurt, sought to rationalize labour in the household through a more efficient kitchen design. You can see a film of the Frankfurt Kitchen (1926) here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=41pyty0-lgs">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

87 Frank and Lilian Gilbreth took efficiency as gospel (perhaps in part because they had 12 kids). Their Time and Motion Studies were a systematic way of analysing any task and trying to make it more efficient. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lDg9REgkCQk&t=6s">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

88 Norma and Normman (1943) were examples of the obsession with standards that came out of factory life. They are representative estimations of average American man and women taken from two large data sets.

89 They were shown in museums in New York and Cleveland, where the public were fascinated by their beauty. An Ohio paper put out a competition to find the woman who most closely matched Norma, and here is the winner. (No such search for Normman!)

90 Finally, it& #39;s no coincidence that the city that invented mass-produced cars also invented the music production system of Motown. Here’s Martha and the Vandellas singing in the River Rouge Plant, while the line was still moving. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K3L-nJMyMPI">https://www.youtube.com/watch... Stone cold classic.

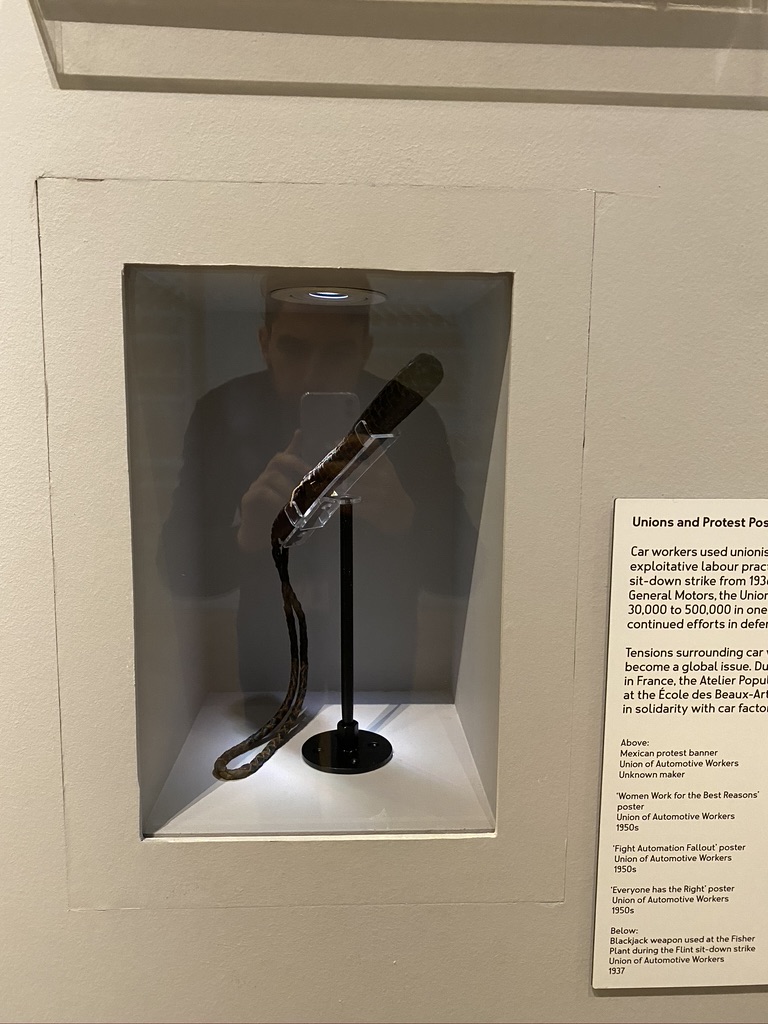

91 Detroit also helped set the tenor of labour rights in the 20th century through the steadfast work of the United Auto Workers union. These posters they produced in the 1950s still speak to issues we are grappling with today.

92 The fight to unionize was fierce and bloody. Here is a homemade weapon used in the Flint sit-down strike of 1937 against General Motors. The success of this strike turned the tides leading to labour representation at all the major car makers in Detroit.

93 Of course, a big fear amongst workers in car factories has been automation. This is the first ever robot used in a factory, the Unimate. It was introduced in 1961 to a GM factory in Trenton, New Jersey.

94 This promo film (1968) for the Unimate imagines how it might be useful in the home. It includes one of the worst champagne pours in history. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VdolSBpyCaU">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

95 To show how far we have come since the moving assembly line, we shot inside the BMW factory in Munich. We tried to create a 1:1 window into an automated landscape with hardly a person in sight.

Alright I know this is getting long, and I& #39;m sure most of you have had more than enough - but hear me out, I& #39;ve started this thing and now I need to finish it. (I& #39;m about halfway, twitter is hard)

96 From mass-production we turn to mass-consumption to explore how the car industry came up with new ways to sell cars to the people. If you can all of a sudden make a million cars, you need to find ways to sell them too.

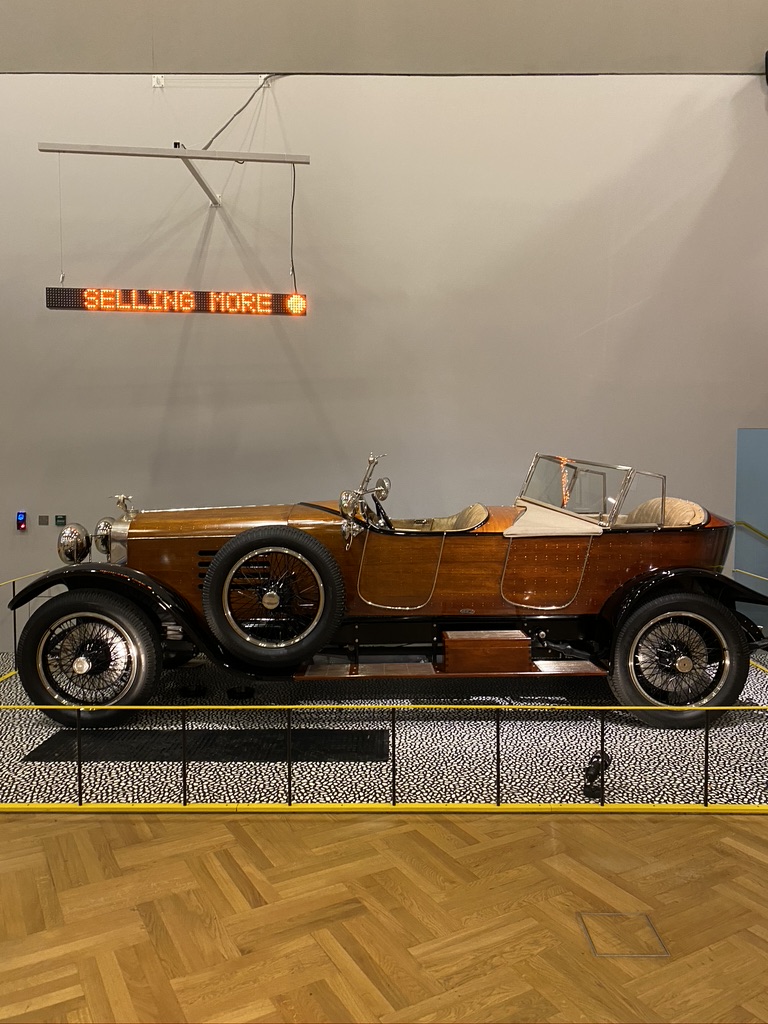

97 Let’s start by looking at luxury cars, the polar opposite of the Model T. At the beginning of the century there was a booming industry for bespoke handcrafted cars like this Hispano Suiza ‘Skiff Torpedo’ from 1922.

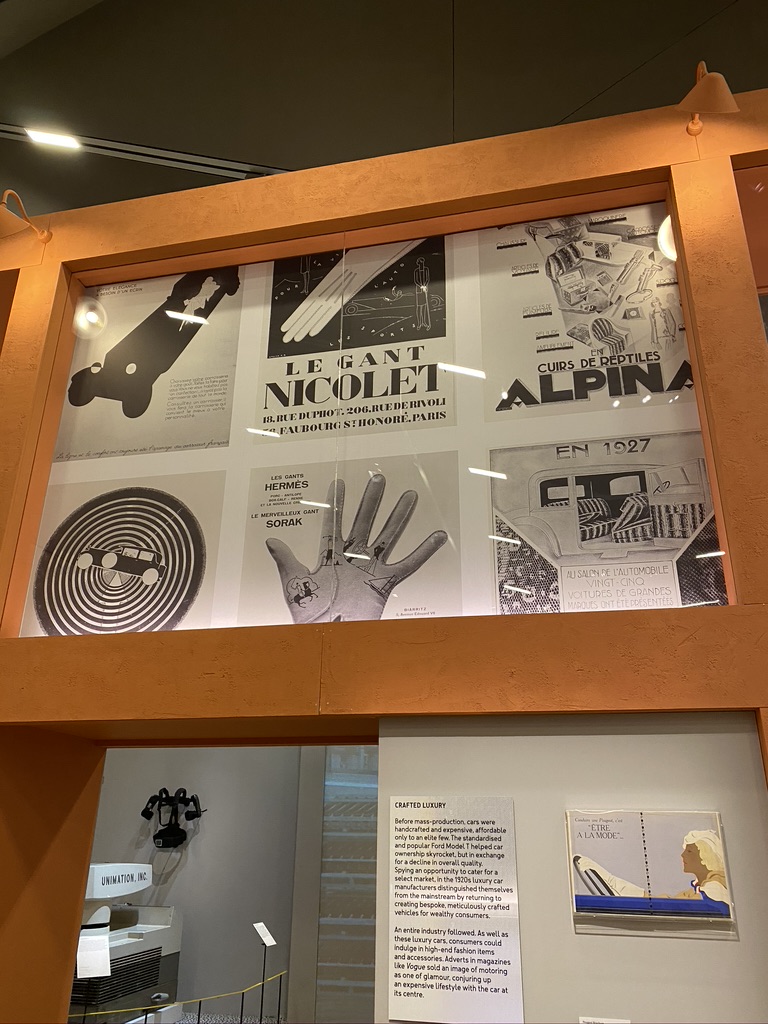

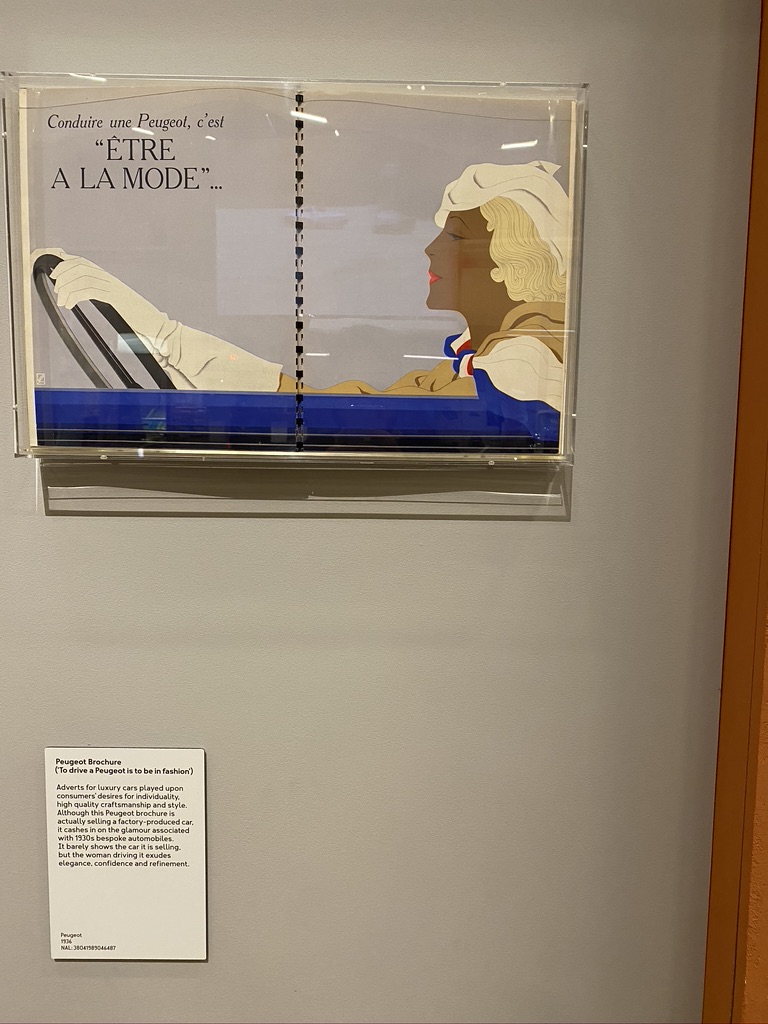

98 They would have cost an enormous amount to purchase – a true signifier of your wealth. Vogue magazine in the 1920s is full of luxury brands that pivoted to automotive fashion accessories, Hermes driving gloves, LV luggage and so on.

99 The conspicuous display of wealth was so extreme that you would hire the most famous glass maker of the time, René Lalique, to make glass hood ornaments for your car. Here are a few. Not the most practical material for bumpy rides.

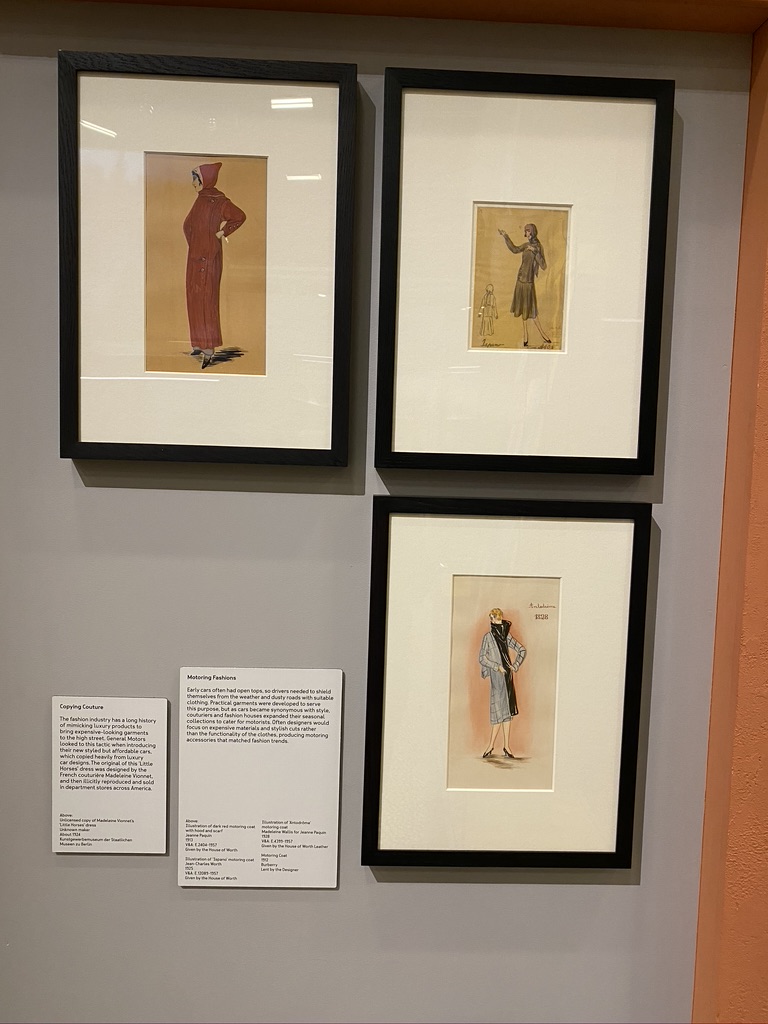

100 A whole new subset of ‘motoring fashion’ emerged, specific outfits to wear while driving. Burberry was quick to pick up on this trend.

101 All well and good for the luxury brands, but what if your market was the middle class? You were left with a problem – the Ford Model T was impossible to compete with. This is where General Motors started a revolution.

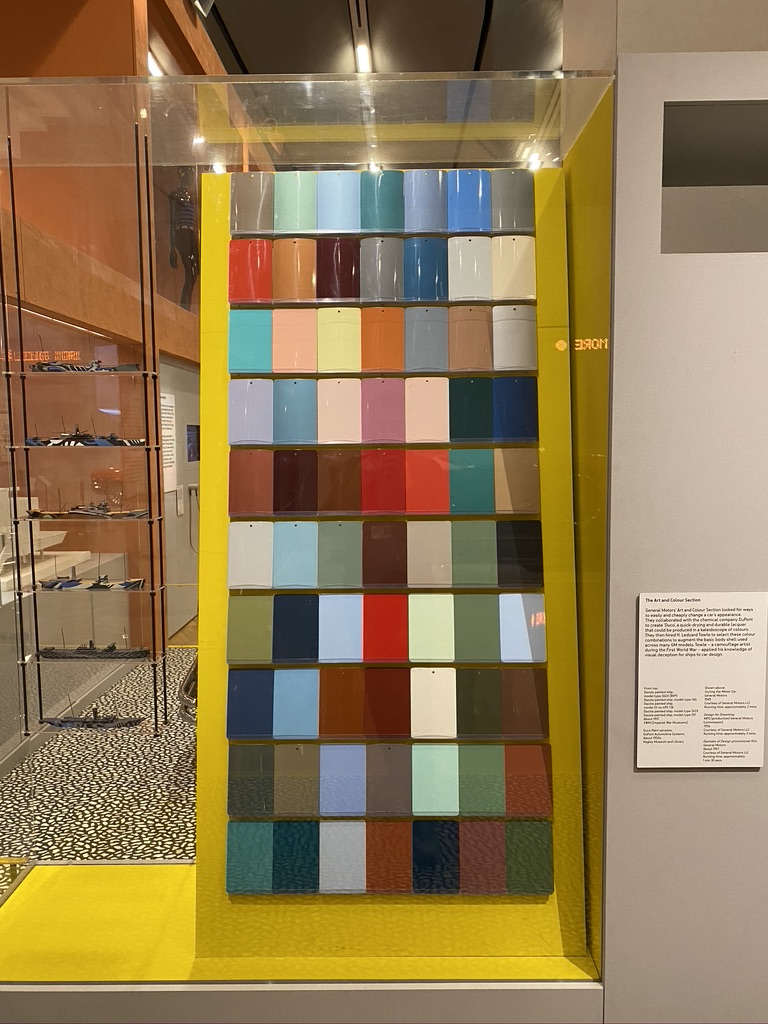

102 The CEO Alfred Sloan looked to the Paris fashion system and saw two takeaways: you can motivate people to keep buying new things every year even if you don’t need it. He also saw how high-end fashions were quickly copied by local shops and sold cheaply.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter