Hi everyone. @Rob_Haug checking in. I want to begin by thanking @sasanianshah for not only inviting me to take over this handle for the week (when I know quarantines mean I have a captive audience), but also thank him for making this fantastic resource in the first place. rh 1/

As Khodadad already mentioned, I’m Associate Prof of Islamic World History at the University of Cincinnati and author of The Eastern Frontier: Limits of Empire in Late Antique and Early Medieval Central Asia. rh 2/

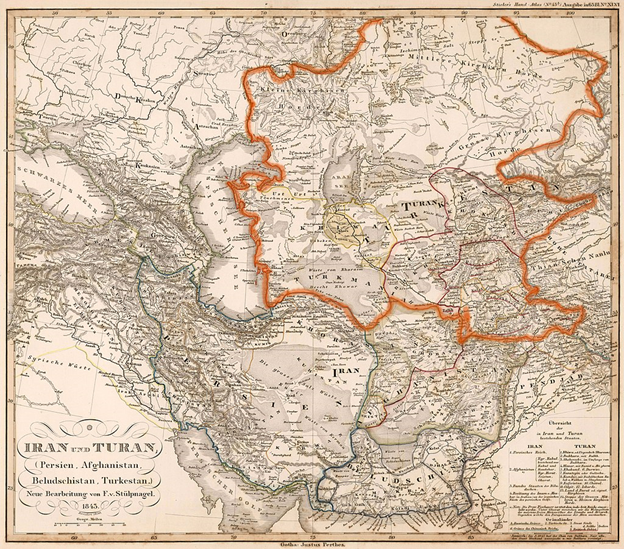

I bring this up not only because I am a self-promoter, but also because that is the subject I want to talk about this week… frontiers. In particular, I want to talk about the eastern frontiers of the Iranian world with special emphasis on the Central Asian frontier. rh 3/

To start, let’s talk about pre-modern frontiers in general. Most of us remember a map like this from elementary school. This is the kind of world map that might hang in front of a classroom and it is this kind of map which informed our understanding of political geography. rh 4/

This map has a couple key features I would like us to think about. First, it has nicely defined borders, black lines dividing neatly labeled countries. Second, those countries appear as solid colored shapes. Combined, these create a certain image of political geography. rh 5/

For this next bit, I am borrowing liberally from Thomas Barfield’s Afghanistan: A Cultural and Political History. This is what Barfield calls the “tale of two cheeses”. rh 6/

That world map above with the solidly colored countries gives an American Cheese view of political geography. If we look at China, for example, it is orange and it is evenly orange from north to south, east to west. Implying everything in those borders are equally China. rh 7/

That every bit of China would look the same and, more importantly, would be treated the same by political forces in Beijing. It is all equally China. Kind of like slicing a brick of American Cheese, every piece comes out even and the same. rh 8/

Of course, we know this is totally wrong. Beijing is not Hong Kong is not Xinjiang is not Wuhan is not Tibet, etc. And, of course, this isn’t unique to China. Teaching just across the river from Kentucky, I like to bring up the show Justified to make this point. rh 9/

Reality is that political geography is a lot more like Swiss Cheese. From the perspective of a state, you’ve got your cheese, the bits you want, places that can be easily controlled and taxed and make your state money… rh 10/

And then you’ve got your holes, bits you don’t want, places that are either too difficult to control or don’t produce enough wealth to make it worth the resources to pursue. At worst, these are places the state can’t penetrate. rh 11/

Like the shadowy places of the Lion King’s domain. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bW7PlTaawfQ">https://www.youtube.com/watch... rh 12/

This isn’t a nice clean geography of evenly filled polygons… instead political power and state authority looks more like an archipelago, islands of state control/cheese in a sea of mountains, deserts, steppes, etc./holes. rh 13/

This medieval map of Khurasan, based on the 10th century geography of al-Istakhri, illustrates this principle nicely. Instead of large, evenly filled polygons, you have nodes/cities and the routes that connect them. (Bibliothèque National de France) rh 14/

It might also be useful, to take a phrase from James Scott’s The Art of Not Being Governed, to think of mapping in terms of friction of terrain or distance. Maps that don’t show absolute distances but represent how long or difficult it may be to get from point a to b. rh 15/

As a native Midwesterner who describes all distances in terms of travel time, I of course find this very intuitive. So did a lot of premodern cartographers… here& #39;s the British Museum’s North American Buckskin Map as an example. (I swear, this will get back to Iran…) rh 16/

The physical geography of Eastern Iran and Central Asia makes it is easy to see the challenges of space. Cities and oases act as nodes of state authority but are surrounded by mountains and deserts making it too cost prohibitive to extend that authority. rh 17/

That is until you have helicopters and other forms of terrain flattening technologies that allow one to travel at consistent speeds regardless of territory… h/t to Rambo III for teaching me this lesson at a young age. rh 18/ https://media.giphy.com/media/dxDEPA8LBo8OSxytkk/giphy.gif">https://media.giphy.com/media/dxD...

So, if we should be thinking about premodern political geographies in terms of archipelagos rather than polygons, can we still think about frontiers and borders in terms of lines? Well, of course not! rh 19/

Each of the islands of this archipelago will have, in effect, its own frontier, a limit to which it can assert authority into the countryside. rh 20/

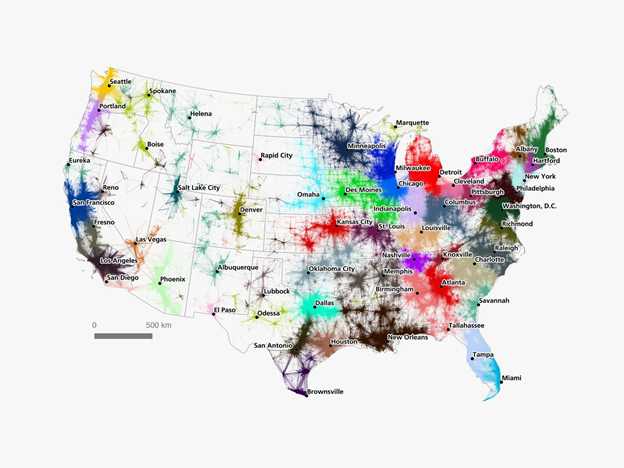

When modern geographers map such networks, what they might call “nodal” or “functional regions”, they are primarily looking at economic connections, as in this map from a 2016 Wired article on American commutes.

https://www.wired.com/2016/12/mesmerizing-commute-maps-reveal-live-mega-regions-not-cities/">https://www.wired.com/2016/12/m... rh 21/

https://www.wired.com/2016/12/mesmerizing-commute-maps-reveal-live-mega-regions-not-cities/">https://www.wired.com/2016/12/m... rh 21/

But in a premodern sense, the emphasis should be more on the exchange of taxes and security. How far out can your node provide security and extract surplus wealth? That’s your functional region or… state. rh 22/

That map of US commutes looks a lot like the Istakhri map above and that’s because geographers like Istakhri did in fact think of the world in these terms. Why do you think so many medieval Arabic geographies are called things like the Book of Routes and Realms! rh 23/

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter