100 years to the 1920 “Nabi Musa Riots”, aka Easter Disturbances, انتفاضة موسم النبي موسى מאורעות תר״פ.

(THREAD)

---------

The Jerusalem riot was the first major Palestinian anti-Zionist violent confrontation, and as such is a contender for “the beginning of the conflict”.

(THREAD)

---------

The Jerusalem riot was the first major Palestinian anti-Zionist violent confrontation, and as such is a contender for “the beginning of the conflict”.

Thinking about the 1920 riots is an opportunity to think through these words, “the conflict”, because it was a moment when events took a turn in that direction, as we now know, but for participants things were yet confusing, unclear, undecided .

I write about Nabi Musa in my forthcoming book, City in Fragments, which looks at Arabic and Hebrew textual artefacts in Jerusalem, and their changing meaning - in this case, the holy velvet banners of Nabi Musa, inscribed in golden thread https://www.sup.org/books/title/?id=26958">https://www.sup.org/books/tit...

So “the facts”, or some of them. The riots took place amidst the annual Muslim celebration of Nabi Musa - a yearly pilgrimage from Jerusalem, Nablus and Hebron to the Muslim tomb of prophet Musa, ie Moses, not far from Jericho.

But let& #39;s stop here, before we start: because this narrative, highlighting the religious occasion, is a choice. It& #39;s hard to resist: not only the colourful and historic details, the banners, the Maqam, but also its colonial manipulation, with the transition to British rule.

The Governor of Jerusalem, Ronald Storrs, tried to use the festival as an arena to co-opt Jerusalem& #39;s Muslim aristocracy - and prove Britain& #39;s benevolent intentions to the local Muslim population (while denying national self determination).

Here is Storrs, son of an Anglican priest, pushing himself into a ceremonial role in a Muslim pilgrimage (1919), mounting the festival& #39;s holy banner on its staff. Next to him, the tall figure of mayor Musa Kazim al-Husayni, who Storrs will sack in 1920 after the riots.

But we can leave the colourful details of the festival to one side, and instead, talk of the heady months of winter 1920, when Arab political mobilisation was building up in the streets of Jerusalem, in cafes, in nationalist clubs, in marches and demonstrations.

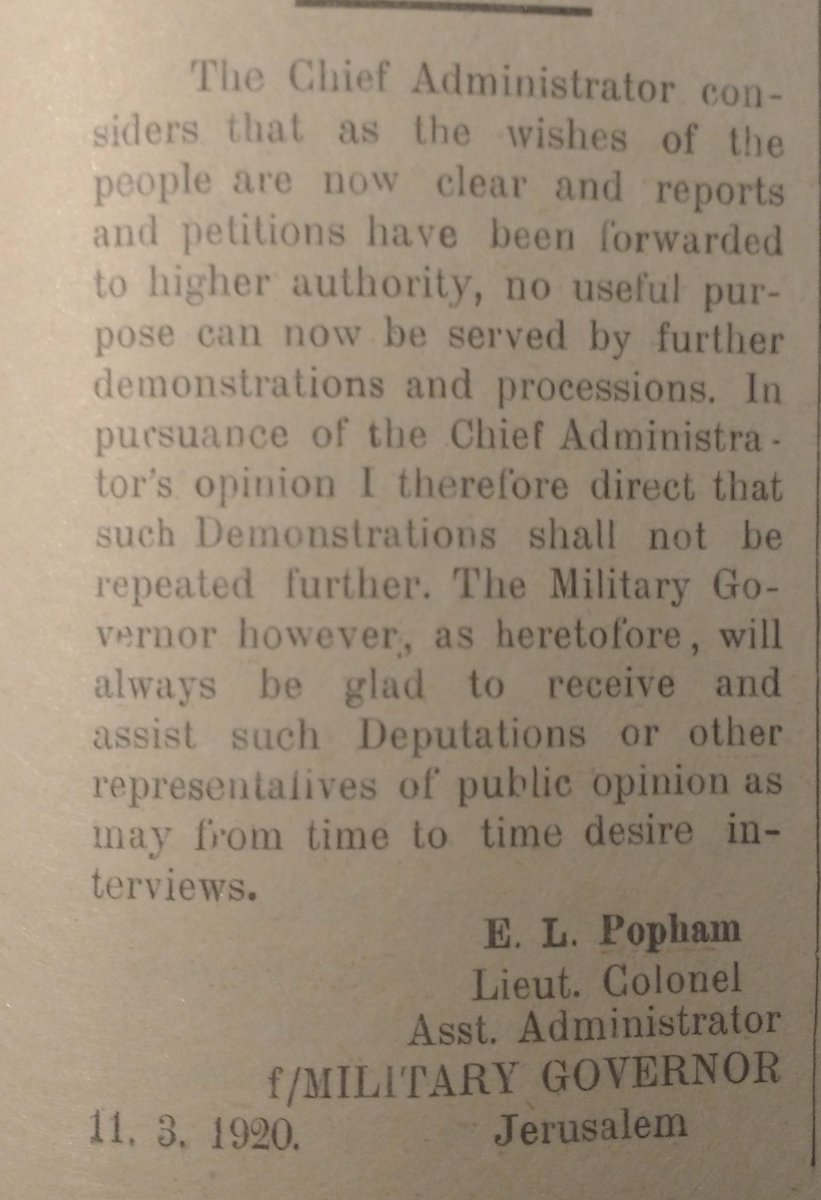

In February and early March, thousands took to the streets, to say no to the Balfour declaration. They demanded that Palestine be a part of a larger Arab state, part of Syria. The Military authorities banned any further demonstrations.

Less than a month later, the Nabi Musa festival was the first public gathering which the British could not prevent. With thousands gathered at the centre of town, political speeches were made against Zionism, from the balconies of the municipality and of local cafes,

And the young Hajj Amin al-Husayni, who just returned from Damascus, shows the crowd an image of Emir Faysal, now "King of Syria" and shouts "This is your King!" And then, suddenly things go wrong: rumours, violence, riot.

Rioters make their way into the walled city, attacking Jewish businesses and Jewish passers-by. British military clamps down and isolate the walled city; some Zionist paramilitaries intervene as well. Five Jews dead, four Arabs, and many more wounded.

Many are arrested; Hajj Amin, seen as chief instigator, escapes arrest and flees the country. Ze& #39;ev Jabotinsky, coordinator of Jewish paramilitaries, is arrested and sent to Acre prison. They would be pardoned later.

So this is the nationalist story, of 1920 as the first violent uprising against Zionism. You will find versions of this story in the suppressed British Inquiry Palin report (1920), in Yehoshua Porath, in the Arabic Wikipedia page on Intifadat Nabi Musa.

But it& #39;s not the only story. And here we can go back to the festival - and listen to the people blamed for the violence, the pilgrims from Hebron, as they testified in front of the commission of Inquiry. And their story is somewhat different.

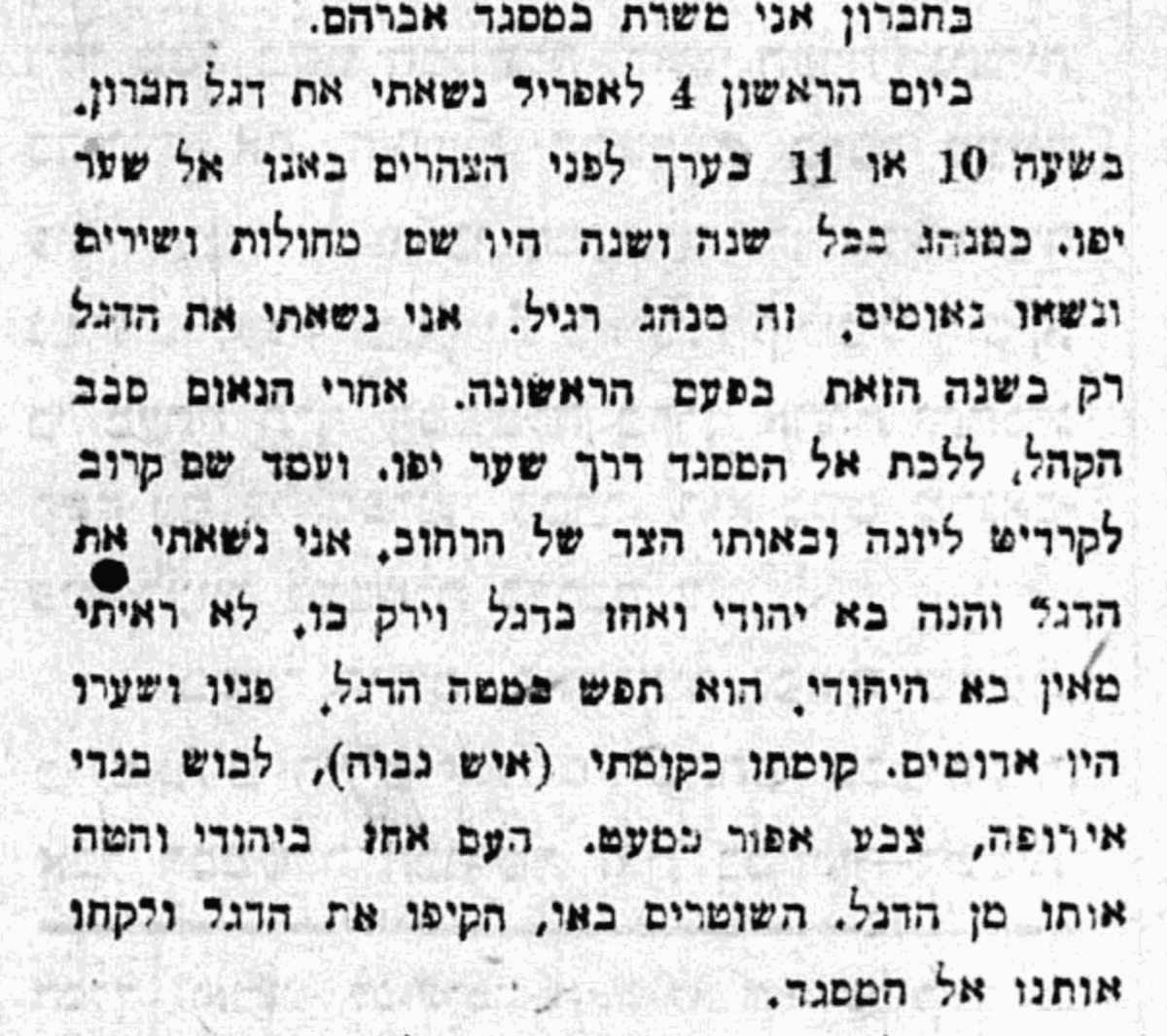

The testimonies of several pilgrims (and at least one British officer) are quoted in Ha& #39;aretz (the newspaper established in 1919). They speak of a conflagration when one "red-faced Jew" tried to grab the Hebron Banner and spat on it.

We even have a name, for the red-faced man. "I know this person" testified one member of the Zionist Commission. "He is my friend, he came from London. His name is Leopold Frank, and his address 49 Westborne Terrace. But now he is Beirut, on his way to Athens".

I have to admit, I did not try to trace Mr. Frank, to see if he left his version to these events. Did he grab the holy banner of Hebron? Did he spit on it? Was this a provocation? A misunderstanding? A false allegation? What we do know, that after this all hell broke.

Crucially, in these testimonies, the riot appears not as an anti-Zionist nationalist Arab mobilisation, but rather as sectarian violence. "Remember the banner of Hebron" rose the cries, "a Jew spat on the banner of Hebron"!

The pilgrims arrived as they did for centuries at the Gate of Hebron (Jaffa Gate), with the banner of Abraham, which they carried from the Ibrahimi mosque, the Cave of the Patriarchs in Hebron. They rose to defend it, from a real or imagined threat.

It should be said, sectarian violence, against Jews or others, was uncommon in Palestine of the late 19th- and early 20th centuries. It was not unheard of, but far less frequent than in Mt. Lebanon, or in other parts of the Ottoman Empire.

So, how do we describe the 1920 Nabi Musa riots? Sectarian violence over holy banners? Or as the first anti-Zionist uprising, triggered by a young nationalist agitator holding a poster of a new King?

I don& #39;t think there is one correct answer.

I don& #39;t think there is one correct answer.

Clearly, British endorsement of the Jewish National Home, and the rejection of Arab political demands, introduced new levels of volatility and tension to the situation on the streets of Jerusalem. It is no accident that this riot erupted in 1920, and not in 1913.

But for the people involved, witnesses, rioters, victims, the differences between religious and national identity, between "Zionists" and local Jews, were far from clear. And when they searched for vocabulary to explain what happened, they chose the one most close to them.

Was the Nabi-Musa riot (which claimed the lives of innocents) an early form of anti-colonial violence? I think so. But it was not necessarily understood and explained as such by the people involved. And it was not necessarily the only form of tension or contradiction.

So the conflict is messy. Not because "it& #39;s complicated" - everything is complicated. It& #39;s messy because there are different and competing explanatory frameworks, which have validity and relevance, in different ways.

It& #39;s not about "two narratives" because when you read the Hebrew and the Arabic wikipedia pages on the riots, yes they differ substantially, but both are nationalist narratives, describing Hajj Amin as the main instigator (villain/leader) - which appears to me highly dubious.

The main driver of the conflict in the last century is the colonial dynamic: the takeover of land by migrants, the dispossession of local population, and their disenfranchisement. But the conflict also has ethno-national dimensions, and sectarian ones. All at the same time.

I leave you with the image of Jerusalem& #39;s District Commissioner E. Keith-Roach overseeing Nabi Musa celebrations, "proud as a peacock" (in the words of the illustrious Arab Jerusalemite Wasif Jawhariyyeh). More in my book.

https://www.sup.org/books/title/?id=26958">https://www.sup.org/books/tit...

https://www.sup.org/books/title/?id=26958">https://www.sup.org/books/tit...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter