The Passover Haggadah is a famously accretive text, and its history has increasingly become clear due to breathtaking discoveries, fascinating individuals, and the support of a variety of institutions. A thread. 1

The Haggadah is comprised of citations from rabbinic literature, late antique Jewish poetry, medieval additions, and many unprovenanced passages, including those that strongly resemble but are absent from rabbinic literature, and some that are entirely unique. 2

Yet despite the many layers, additions, and changes the Haggadah underwent over time, reconstructing the history of its development can be rather difficult. 3

As in so many other areas of Jewish practice, the Haggadah that most Jews are familiar with largely derives from the Babylonian rabbinic tradition, attested in the liturgical handbooks of Amram Gaon (810-875 CE) & Saadia Gaon (882-942 CE), alongside other Geonic passages. 4

What preceded the Babylonian Passover rite is less clear. Often lacking clear smoking guns about the origin of any given passage, scholars are forced to use comparative and linguistic analysis to identify the provenance of any given passage. 5

The Cairo Genizah offered a treasure trove of Haggadah fragments that scholars quickly realized differed from the Babylonian rite that had become pervasive. 6

The story of the discovery, publication, & analysis of these fragments is typical of the intertwining tales of individuals, institutions & ideas that characterize so much of the study of the Genizah esp. in its early years. Curiously, it is also a thoroughly Philadelphia story. 7

Already in the late 19th century, just a few years after the discovery of the Genizah, Solomon Schechter enlisted Israel Abrahams to publish a few fragments of the Haggadah which, in Abrahams& #39; words, were "so obviously important that no lengthy introduction is required." 8

He recognized that these fragments were "further links in the chain which connects our present Hagada with its original form." #metadata_info_tab_contents">https://www.jstor.org/stable/1450605?seq=1 #metadata_info_tab_contents

Yet">https://www.jstor.org/stable/14... Abrahams was short on analysis. 9

Yet">https://www.jstor.org/stable/14... Abrahams was short on analysis. 9

[Incidentally, one of the features of this Hagada that Abrahams identifies as particularly "Egyptian" is the appeal to the Memra or Logos, a central concern of scholarship in the early 2000s, such as the work of Daniel Boyarin and Azzan Yadin]. 10

In 1911, Julius Greenstone published a unique fragment from the Cairo Genizah that he identified as "A fragment of the Passover Haggadah." 11

Greenstone was a conservative rabbi, who headed @mikveh_israel , the oldest synagogue in Philadelphia and one of the oldest in the USA, before joining the faculty at @GratzCollege, the oldest independent college of Jewish Studies, also in Philadelphia. 12

The fragment came from the private collection of David Amram. Amram received a B.A. from the University of Pennsylvania and a law degree from University of Pennsylvania Law School, where he, and eventually his son, held a professorship and specialized in bankruptcy law. 13

Amram also wed his interest in the law with his commitment to Jewish texts and practice, publishing works on law in the bible and Talmud, and eventually, an early work on the history of the Jewish book. For more on Abrams, see here http://ajcarchives.org/AJC_DATA/Files/1941_1942_6_BioSketches.pdf.">https://ajcarchives.org/AJC_DATA/... 14

Amram likely gave the fragment to Greenstone, I& #39;d wager, because, from some online sleuthing, Greenstone& #39;s first wife, who died shortly after he published the fragment, was named Carrie Amram, and must have been David Amram& #39;s daughter. 15

Greenstone& #39;s personal archive is now housed in @TempleUniv, which is, say it with me now, in Philadelphia. https://library.temple.edu/finding_aids/julius-h-greenstone-family-papers.">https://library.temple.edu/finding_a... 16

In 1912, Victor Aptowitzer (born in Galicia in 1871) demonstrated that the blessings in the Genizah "Haggadah" more closely aligned with those in the Palestinian Talmud rather than the Babylonian ("ce qu& #39;elles appartiennent a un rituel pascal palestinien extremement ancien"). 17

One example is the blessing thanking God for "creating a variety of delicacies," found in the Palestinian Talmud and in the work of a Palestinian poet. https://www.academia.edu/42265912/Avigdor_Victor_Aptowitzer_Fragment_d_un_Rituel_de_Paque_originaire_de_Palestine_et_aterieur_au_Talmud_Revue_des_%C3%89tudes_Juives_no._63_1912_124-128.">https://www.academia.edu/42265912/... 18

Alongside his massive erudition and highly influential oeuvre, Aptowitzer trained a generation of Jewish Studies luminaries including Salo Baron and Hanokh Albeck. Thanks to @MyShtender, many of his publications are available here: https://huji.academia.edu/Aptowitzer .">https://huji.academia.edu/Aptowitze... 19

By 1924, Amram& #39;s fragment had been donated to Dropsie College, as it appears in Ben Zion Halper’s Descriptive Catalogue of Genizah Fragments in Philadelphia (p. 99) of that year. This is when it receives its current call number of Halper 211. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015034761448&view=1up&seq=103.">https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt... 20

Founded in 1907, Dropsie College was the first accredited Jewish Studies doctoral granting institution in the world. 21

It was founded at the bequest of Moses Aaron Dropsie. A Philadelphian from birth to death, Dropsie was a mayoral candidate, abolitionist, & helped build trains and a bridge over the Schuylkill River. 22

He was also president of many Jewish institutions in Philly, including Maimonides College, Alliance Israélite Universelle, and Gratz college. http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/5331-dropsie-moses-aaron.">https://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/... 23

Dropsie College was home to many fabulous scholars, including for a three year stint the too-early departed Baruch Bokser, whose seminal book "The Origins of the Seder" argued that the Passover Haggadah was produced in response to the destruction of the second temple in 70 CE. 24

He crucially highlighted parallels between the Haggadah and the ritualized elite banquet that was the Greek Symposium (and Roman Convivium). The NYTimes published his obituary: https://www.nytimes.com/1990/07/13/obituaries/baruch-m-bokser-44-a-professor-of-talmud.html.">https://www.nytimes.com/1990/07/1... 25 (Continues in next thread, follow the numbers!)

Briefly leaving the confines of Philadelphia, in 1969, Ernst Daniel Golschmidt published a full facsimile and edition of Halper 211 with extensive introduction and commentary. 26

Born in Poland at the turn of the 20th century, he was a scholar of Jewish liturgy who joined the staff of the then Jewish National and University Library (now @NLIsrael ), and whose publications reflect a keen interest in the history of the Haggadah. 27

Where Aptowitzer focused primarily on the blessings at the outset of the Haggadah, Goldschmidt studied the fragment in its entirety. He noted many additional differences between the standard Babylonian rite and the one reflected in the fragments. 28

These including the absence of the opening Aramaic portion (& #39;Ha Lakhma Anya"), a list of three questions asked by children rather than four, and the absence of a number of passages in the Babylonian rite after the three questions. 29

In these last two features, the Palestinian rite closely follows Mishnah Pesachim 10:4, and do not include the many additions that entered the Haggadah in Babylonia during and following the Amoraic period. 30

This rite lacks a question querying why one leans on Passover evening versus every other night, presumably because it remained common practice to lean on other nights! Only as the Haggadah traveled out of Palestine did leaning become particularly exceptional and noteworthy. 31

Incidentally, Goldschmidt also showed that when Natronai Gaon (d. 858 CE) described and lambasted a particular Passover rite, which he labeled as Karaite, he was referring to the same rite evidenced in these Genizah fragments. 32

However, as Abrahams already noted, in deploying the Karaite label, Natronai was denigrating this rival practice rather than identifying their origin as genuinely Karaitic, as the Genizah fragments include plenty of rabbinic material. 33

For a field changing study contrasting discourses of the Rabbanite-Karaite split versus social reality, see, of course, @mrustow& #39;s first book. 34

In 1986, Dropsie was reconstituted as a postdoctoral research center known as the Annenberg Research Institute, before it was folded into University of Pennsylvania and being reconstituted as the @katzcenterupenn. 35

What was left of Dropsie& #39;s rich collection of manuscripts and artifacts after a fire and a surprising amount of theft is now housed at the Katz Center, which has digitized Halper 211 for your viewing pleasure: http://openn.library.upenn.edu/Data/0002/html/h211.html.">https://openn.library.upenn.edu/Data/0002... 36

Yet, stealing some of Philly& #39;s thunder, Jay Rovner argued that a fragment in @JTSVoice (MS 9560) preserved a still earlier version of the Palestinian rite, which is dated to the late 10th-11th centuries on paleographic grounds #metadata_info_tab_contents">https://www.jstor.org/stable/1454759?seq=1 #metadata_info_tab_contents.">https://www.jstor.org/stable/14... 37

It must be said that the differences that Rovner identifies might, instead, be attributable not to a time gap between these works, but rather to their forms - Halper 211 is a Siddur or Maḥzor, whereas JTS, in Rovner& #39;s words, "gives every sign of being a layman& #39;s production." 38

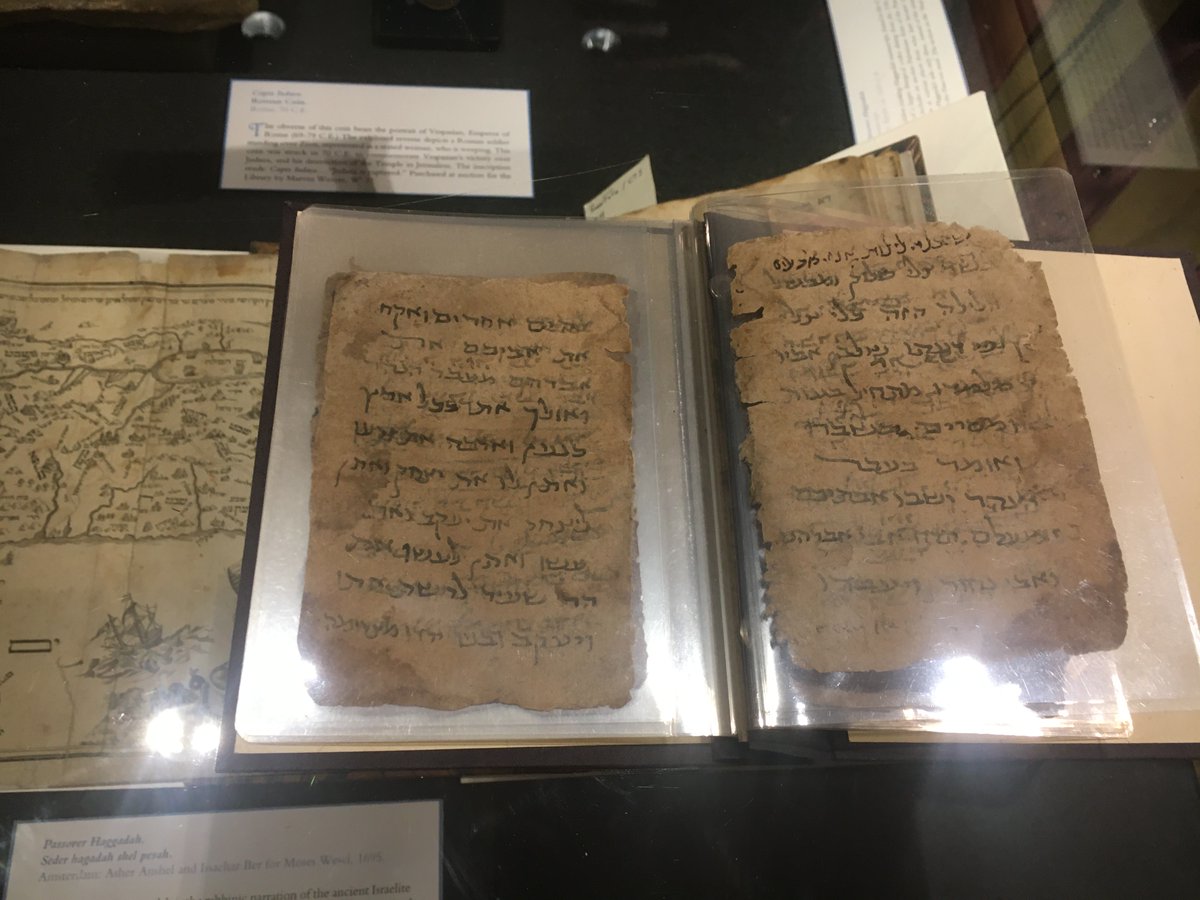

Interestingly, most of these works from the late 19th century through the beginning of the 21st century, including Rovner& #39;s, were published in the @TheJQR , out of the University of Pennsylvania. Philly still gets the final word! 39

I was fortunate enough to see and handle these fragments a few weeks prior to social-isolation with the inimitable and indefatigable Arthur Kiron of @upennlib and @katzcenterupenn. 40

Though fragments are digitized and viewable online, in my excitement I took some fairly terrible pictures in my attempt to highlight the relatively compact size of the fragments. 41

This is only the beginning of the story! There is much work still to be done on the provenance of many features of the Haggadah, including a piece that I recently submitted but which is still under review, so perhaps more at a future date! 42/end.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter