Okay, I& #39;ve been wanting to write this post for a while, so here it goes: prisons+jail reform has a LONG history with disease. Let me explain.... 1/n

Before I go on, let me first acknowledge #MichaelMeranze whose excellent book #LaboratoriesofVirtue makes disease a major focal point in his history of post-Revolution penal reform. 2/n https://www.amazon.com/Laboratories-Virtue-Punishment-Revolution-Philadelphia/dp/0807856312">https://www.amazon.com/Laborator...

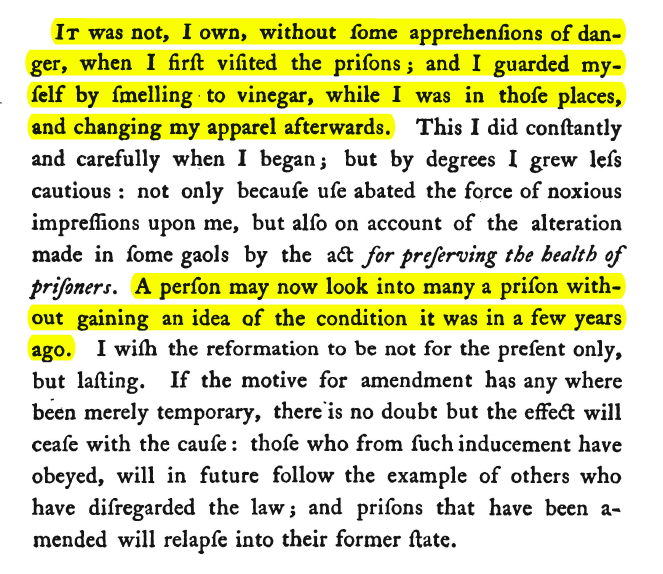

Okay, like a lot of scholars, I think of British reformer John Howard as one of the most important actors in the story of how we got prisons as we understand them today. One of his major motivations for starting reform was the level of disease in local gaols/jails. 3/n

In John Howard& #39;s time (1770s), we didn& #39;t have prisons as we know them today; we had jails. County jails were overcrowded, filthy, disease-infested, dangerous places. They were way pre-bureaucratic holding tanks for a big mix of people. 4/n

Jails held debtors, vagrants, people awaiting trial, people awaiting their punishment, people already tried (found guilty or not) and already punished but who still owed fees and fines. Men, women, children, old people, hardened criminals, and "impressionable" innocents. 5/n

They were kept in large rooms, all together, no separation, minimal or no supervision, no activities typically, no work (except for some types of jails not called jails). There was violence. And disease spread rapidly. 6/n

And as I said, they were pretty gross places that smelled atrocious. When elite reformers visited, they used vinegar and smelling agents to muffle the smell and protect their own health. 7/n

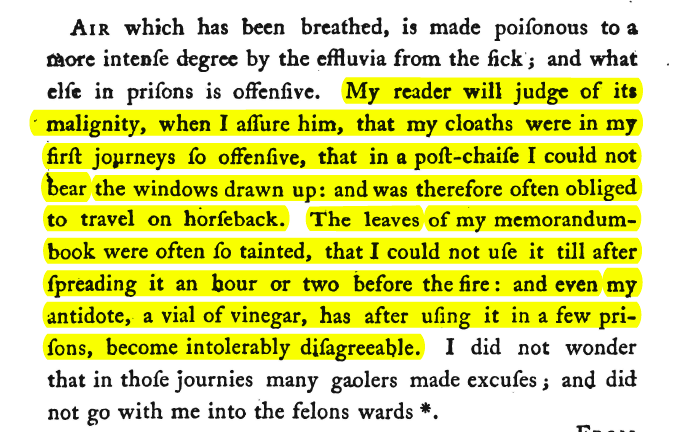

So bad was the smell that Howard& #39;s clothing and notebook continued to smell after visiting. He couldn& #39;t ride in carriages bc the smell was so bad.

But it wasn& #39;t just the smell. The smell was a product of lack of hygiene that also helped disease to spread rapidly, particularly in such overcrowded facilities with no separation between prisoners. 9/n

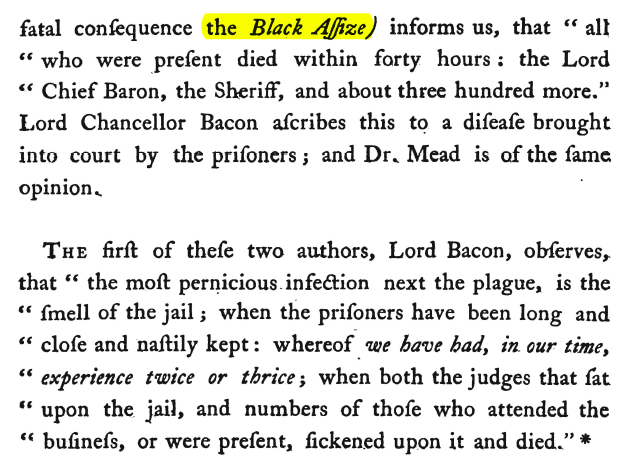

Just how dangerous were jails? One notorious episode stood out for Howard (which he wrote about in his first major book on prisons): The Black Assize of 1577. (Assize is a type of court.) Prisoners were brought in for trial and within 40 hours, many of the courtiers were dead. 10

With these fears in mind, Howard outlined multiple reforms to county jails that would prevent the spread of disease (as well as violence and the spread of criminality). These reforms became the basis of our first state prisons in the US & laid the groundwork for later prisons. 11

Speaking of the spread of criminality, as Meranze explains in his book, one of the leading understandings of how crime spread was a kind of disease model, the miasma theory. In the US, Dr. Benjamin Rush (who fought the yellow fever epidemic) was a big believer. 12

The idea is like pestilence, criminality can almost be breathed in by being in close proximity with criminals. An impressionable innocent (say, a debtor& #39;s son) in jail with a dashing but hardened criminal could "catch" criminality. This is a recurring fear we still hear about. 13

The twin concerns that inmates of jails and prisons could catch disease and criminality from one another were major motivations behind the use of solitary confinement around the country in our first two iterations of prison (in the 1790s+ and the 1820s+). 14

[Quick pause to walk my dog. Be back... later.]

[This was longer than a quick pause.]

When we did get new prisons (the first batch starting in the 1790s and the second in the 1820s), controlling and preventing disease was a major theme. 15

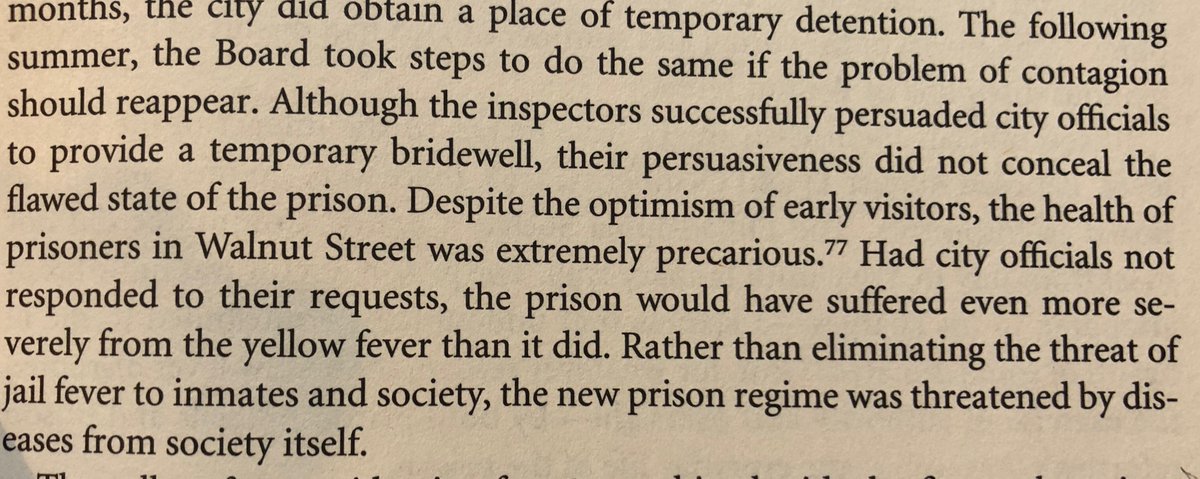

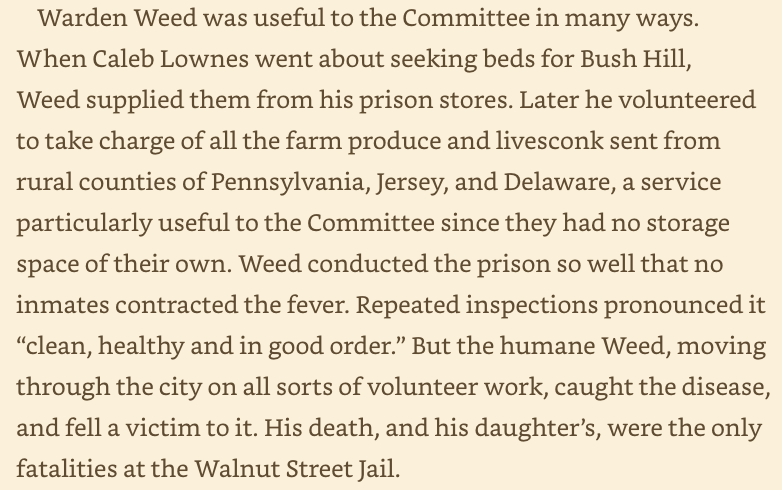

In particular, in times of disease outbreak, local officials and reformers *recognized* that prisons were both sites of possible atrocities and possible causes to spread the disease further. Here& #39;s an excerpt from Meranze& #39;s book about Philadelphia& #39;s Yellow Fever outbreak of 1798.

That yellow fever outbreak had other consequences for Walnut Street Prison (the model prison for the country at the time). I talk about it in my book, here drawing on Meranze. 17/n

While I& #39;m on yellow fever in Philadelphia, there is a great book about the 1793 outbreak by Jim Murphy called an American Plague. See if this sounds familiar? Yellow fever is caused by mosquitos, by the way, and was a recurring problem in major US cities (and elsewhere).

We& #39;ve recently seen news articles about prisoners being hired to dig mass graves today in the US. In the 1793 yellow fever outbreak, black prisoners were used to *treat* the sick. (Sorry for the outdated language in this image.) Source: Powell& #39;s classic Bring Out Your Dead.

One of my favorite uses of history is to look for similarities and difference. Here& #39;s another episode from the 1793 yellow fever outbreak in Powell& #39;s book. Notice the contrast to today?

Okay, moving beyond the Yellow Fever epidemics, the point is that diseases and esp outbreaks were really big issues when we were first designing prisons. Our concern for prisoners& #39; health was a big part of why prisons looked the way they did.

Moreover, post-reform prisons were often scrutinized for how healthy their prisoners were. Many prisons, even post-reform, continued to keep their prisoners in bad conditions, but the expectation and aspiration was to do better. The designs and the rhetoric were about health.

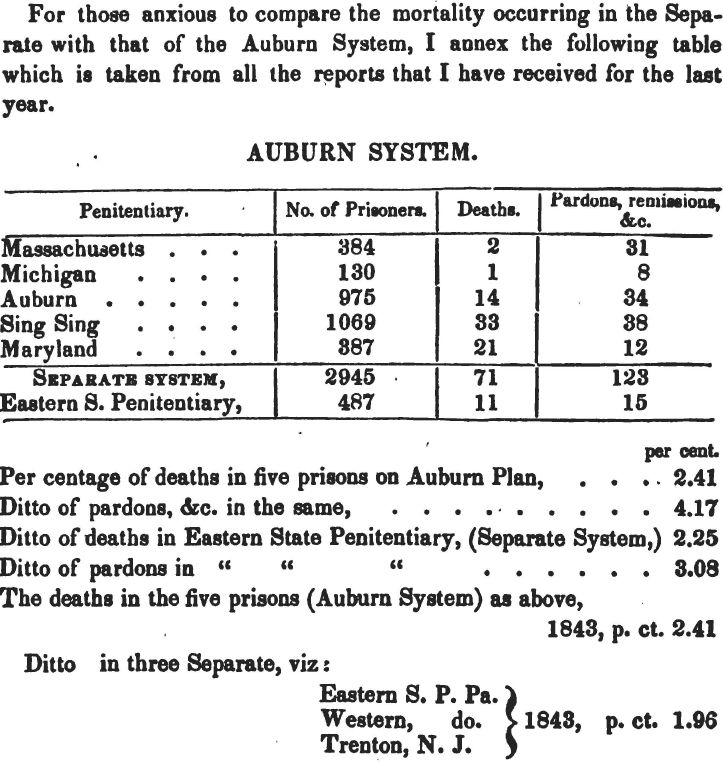

Here is a typical excerpt from a prison& #39;s annual report ( @easternstate, actually) comparing the mortality of its prisoners to other prisons& #39; mortality rates. (This from 1844.)

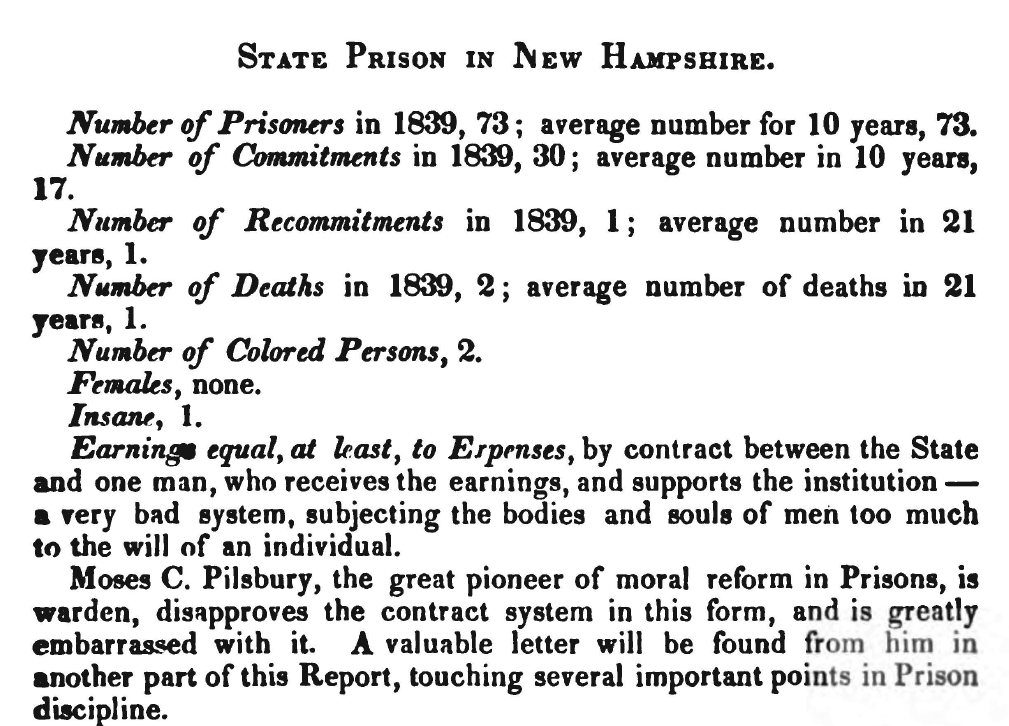

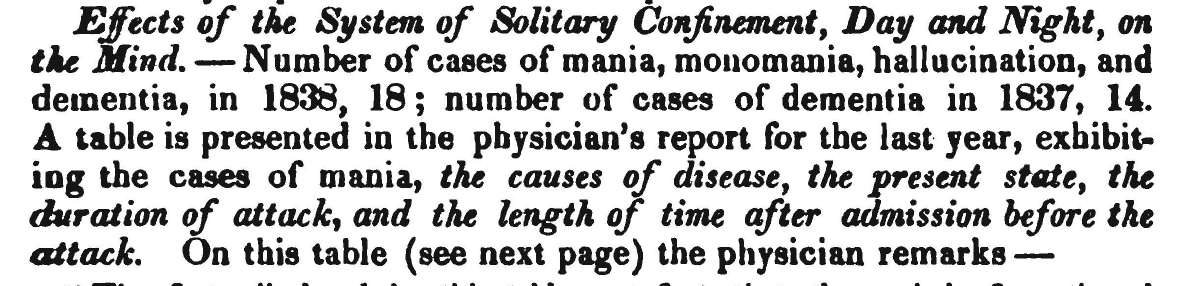

They weren& #39;t just putting these in because no one cared. People reviewed the records and criticized this and other prisons for their mortality and disease rates (among other things). Here& #39;s an 1839 excerpt from the Boston Prison Discipline Society, which was one such watchdog.

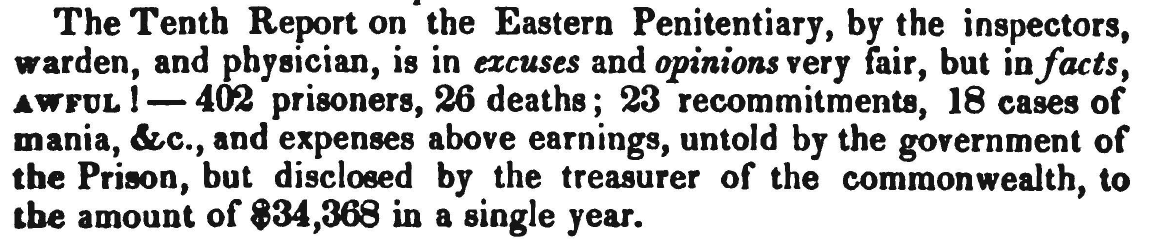

A big part of the reason for this attention was the belief that prison made people sick (mentally and/or physically). Eastern in particular was scrutinized because of its round-the-clock use of solitary confinement. The BPDS interrupted all deaths and insanity as evidence.

Here& #39;s my favorite quote (again from the 1839 BPDS report) where they are almost yelling at how bad and pointless the prison regime was.

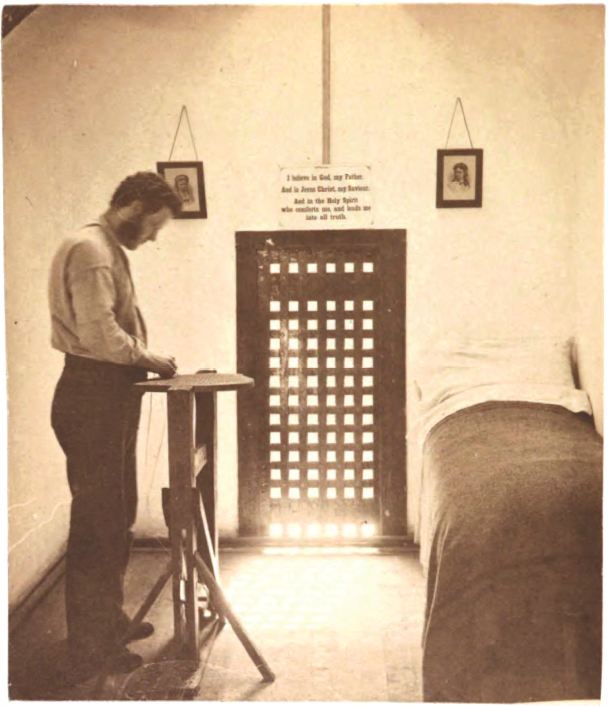

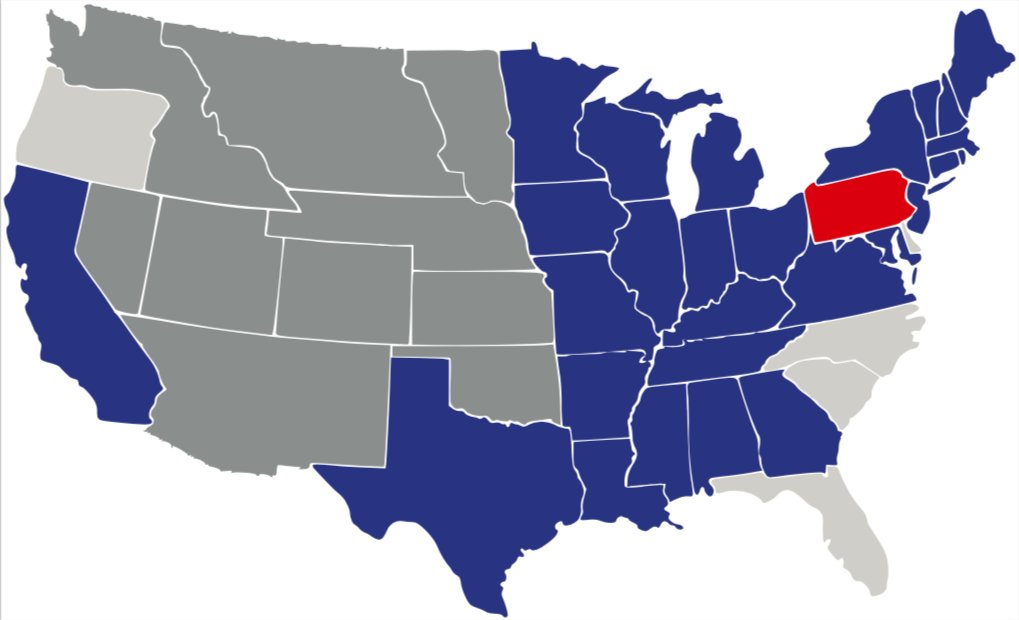

The belief that Eastern& #39;s use of routine solitary confinement was so bad for prisoners& #39; mental and physical health is one of two major reasons why our prisons were modeled after New York& #39;s Auburn State Prison and its factory model and not Eastern& #39;s separate system (pic below).

Let& #39;s move from external criticism back inside to what prisons were doing. Did you know that early prisons (1820s) had staff physicians? At @easternstate, the staff physician had almost as much authority as the warden; he (always a he) could overrule the warden regarding health.

Eastern also sometimes had an apothecary, a role sometimes staffed by a prisoner and sometimes by someone else.

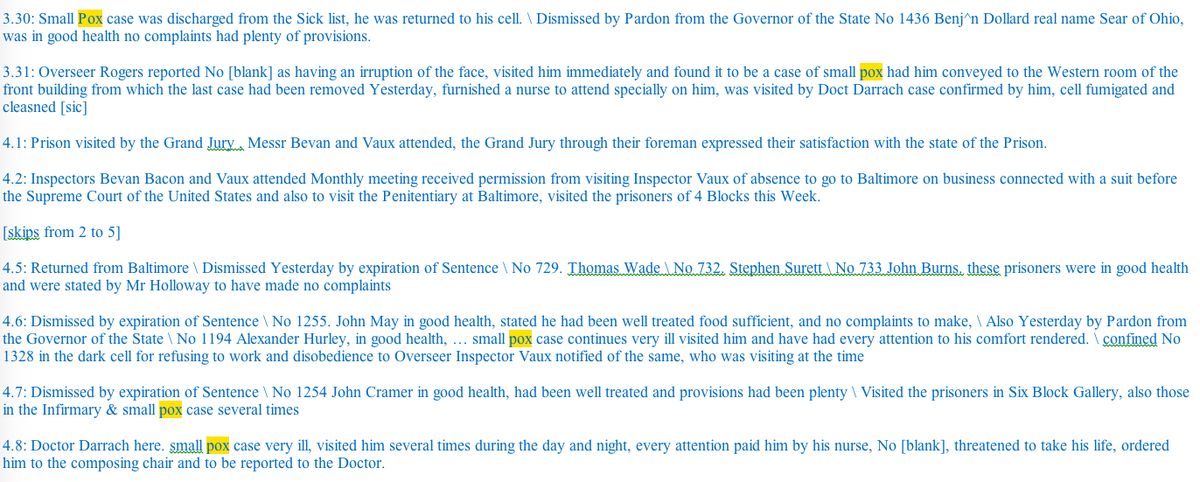

When a prisoner was seriously ill, wardens took it seriously. Here& #39;s an excerpt from Eastern& #39;s warden& #39;s log in 1842 (my transcription of archival docs). It shows how a smallpox case was handled, esp by the warden.

The story continues a few weeks later as the pox spreads. Since it& #39;s mixed in with other notes, pox is highlighted.

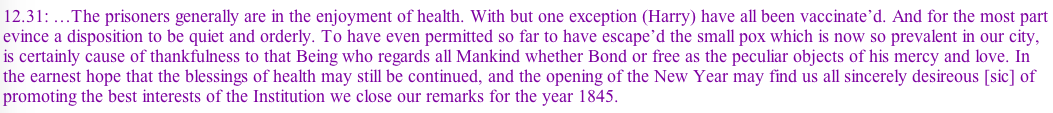

It goes on, but you get the idea. Small pox was a big deal for prisons. You can understand the next Warden& #39;s rejoicing on the last day of the year in 1845 noting how they were spared despite the outbreak in the city less than two miles away.

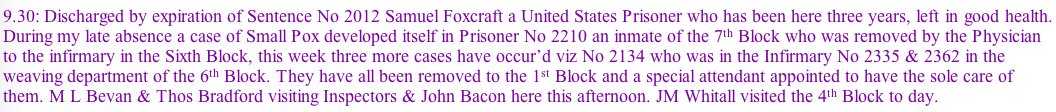

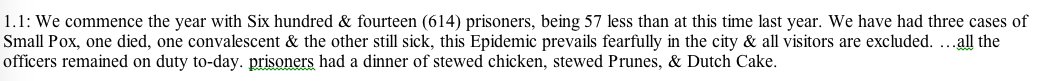

Here& #39;s another little episode, another smallpox outbreak, now in 1848, same warden who was just rejoicing in late 1845. Again, they took this shit seriously.

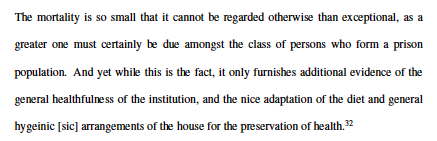

Wardens& #39; attention on disease was not just about preventing its spread, but also the reputational damage that came with a large death rate. Having a low death rate gave them bragging rights, as in this one from 1862 (excerpted from my book).

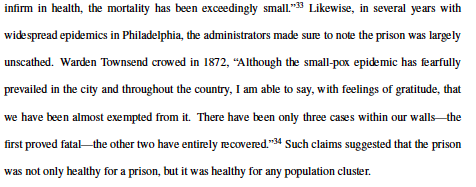

Having low rates of disease and mortality was especially brag worthy during epidemics. Again, from my book:

Think about that for a minute: wouldn& #39;t it be great to see our prisons and jails *competing* with one another over who had lower mortality and disease rates? Over who had better hygiene regimens?

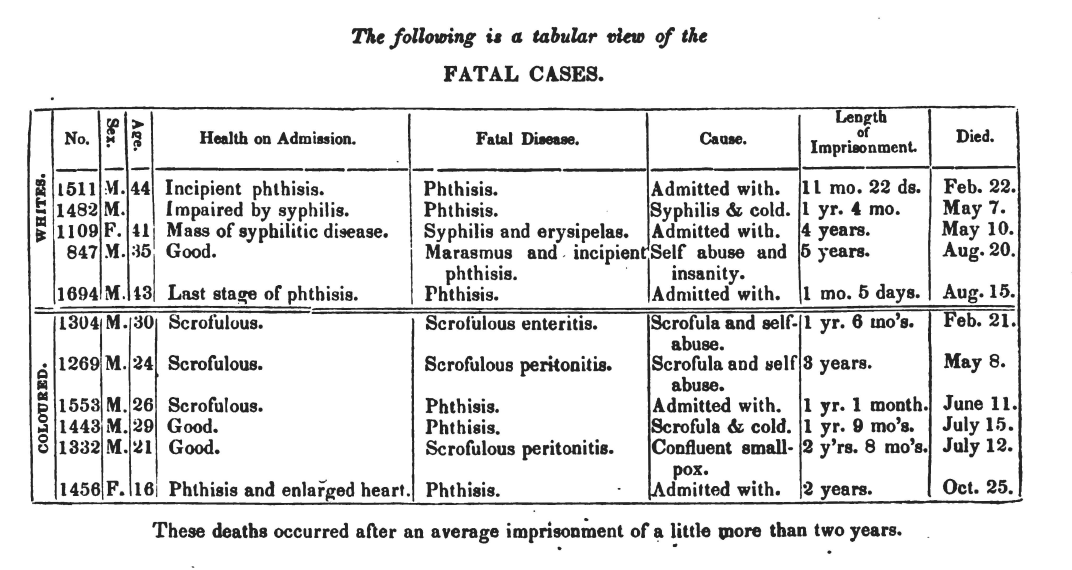

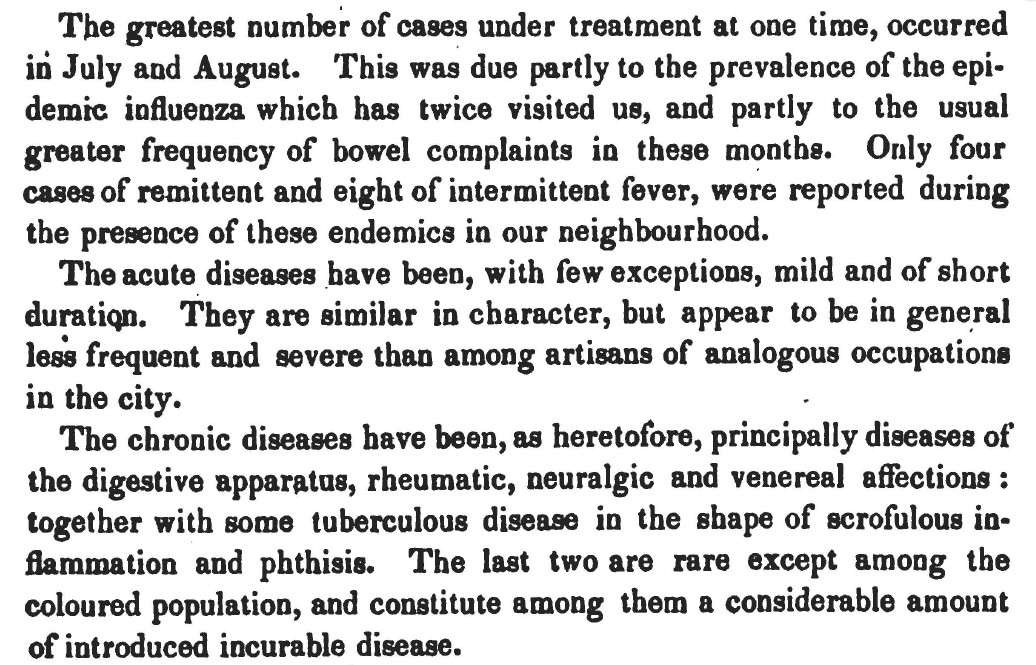

Of course, even in the prison claiming to be the most humane, the administrators still blamed the prisoners, as well as state policy and economic downturns, when the rates of illness were too high. They esp liked to blame insanity on... um... well... "mst."

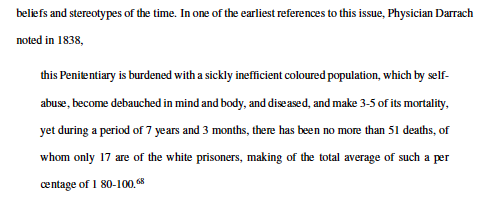

They were also pretty racist in this process, blaming their black prisoners on being predisposed to poor health and *for not being well disposed to confinement.* In fact, several prison administrators opposed having black people in prison for this and other reasons.

Additionally, they claimed that their higher rates of disease also impacted the prison& #39;s industries and ability to prove self-sufficient.* Sick prisoners can& #39;t work.

*Profit was never really realistic, and the admin often changed their tune on whether they expected profit.

*Profit was never really realistic, and the admin often changed their tune on whether they expected profit.

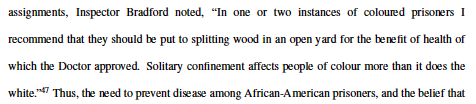

In fact, beliefs about racial differences in predisposition to disease would also impact their work assignments. For example:

Disease also came up in their opposition to overcrowding. Prison admin generally don& #39;t like overcrowding. It& #39;s dangerous, both in the sense of violence and disorder, but also disease outbreaks. When Eastern got overcrowded, admin used disease as one reason why this was bad.

I left this out from my earlier discussion about jail/prison reform in 1790s/1810s/1820s Philadelphia. These are from Meranze and his discussion of how disease and immorality (including crime) were linked in the middle/upper class/officials& #39; imagination.

The linkage between morality and disease didn& #39;t really go away. Eastern admin changed the name of their "separate system" (i.e., solitary with some other stuff) to the "individual treatment system" after overcrowding struck. Treatment of what? Mostly something like rehab....

Indeed, in this era more generally, reformers and nascent criminologists identified (or tried to identify) hereditary (i.e., genetic--but before we knew about genes) links in the familial spread of crime, disease, pauperism, and immorality (e.g., prostitution).

This (1860s+) is also the era where we see the rise of another medical model of treating criminality. Eventually, indeterminate sentences are justified under the idea that doctors are not given limits for how long to treat a disease. Hence, we get things like parole.

I& #39;m being a bit sloppy here with the dates, but that& #39;s partly because you could argue that basically 1860s-1960s are part of one big medical model era.

And now I have an obligatory reference to Foucault who discusses the rise of the psy- experts in this period.

Others have been tweeting about Foucault and his examination of quarantines, etc., including @KoehlerJA https://twitter.com/KoehlerJA/status/1242773249358024704">https://twitter.com/KoehlerJA...

Now, in looking for that tweet by Johann, I just found that he& #39;d already posted these gems from Howard: https://twitter.com/KoehlerJA/status/1244957753216569344">https://twitter.com/KoehlerJA...

Okay, going back to the way in which disease is intricately bound up with jail/prison reform, I mentioned Howard& #39;s plan and how it set the basis for our (US) prisons. The relative safety of reformed/Walnut Street-style prisons (1790s-1810s) was a major selling point.

Politicians, reformers, and others visited Philadelphia& #39;s Walnut Street prison and wrote tracts about how great it was--to convince their govts to adopt a similar facility. Here& #39;s from a bit I cut from my forthcoming book where they talk about its relative healthfulness.

The "they" here includes Robert Turnbull (South Carolina) and French social reformer Francois Alexandre Frederic, Duc de la Rochefoucauld-Liancourt.

So, I keep mentioning that disease/mortality was one of a few concerns that motivated jail/prison reform. What were the others? Expense/profitability, feasibility, and efficacy re: rehabilitation (as measured by recidivism). Over time, we seem to care less about these concerns.

Okay, back to how concern about disease helped propel particular models of prison. So, Walnut Street was the first US model for prison (1790s+). Auburn State prison was the second (1820s+).

Again, the contrast to the disease-ridden prison facilities the new Auburn facility was replacing was one of several factors promoters used to explain why states should adopt this particular prison& #39;s design. (From an earlier version of my book.)

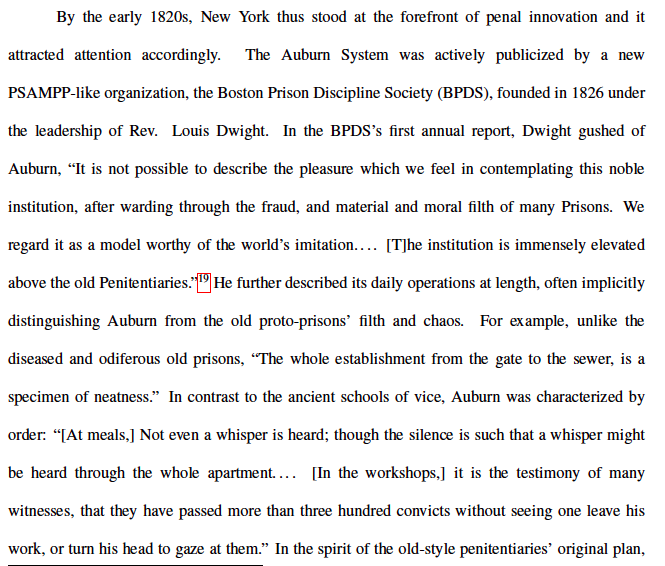

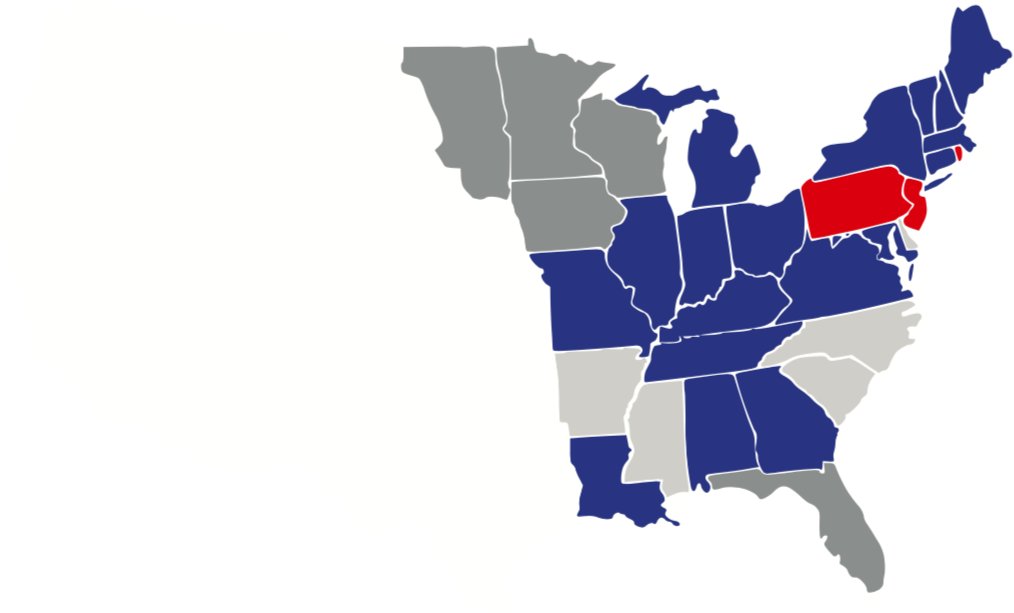

How successful were these arguments? Well, this is the spread (in 1800, 1810, and 1825) of the first-gen prisons.

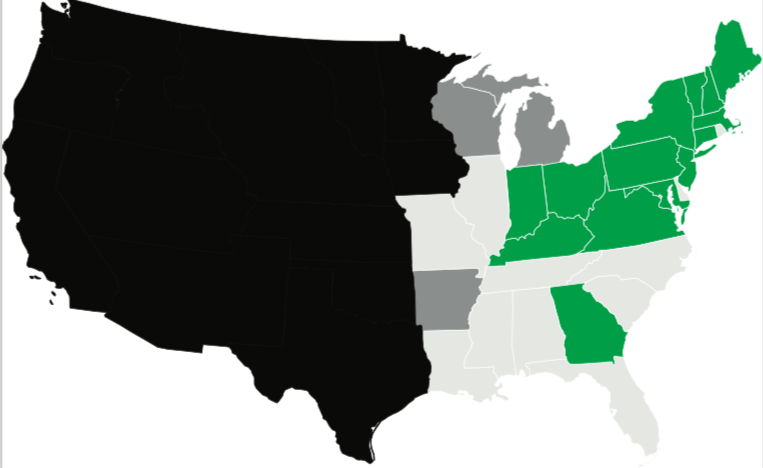

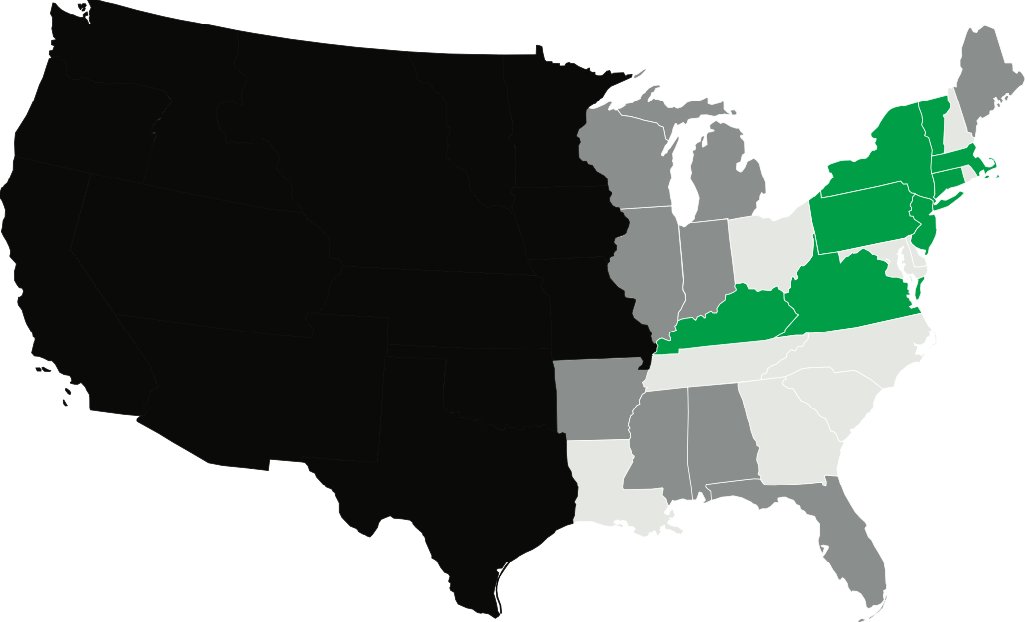

And this is the spread (in 1821, 1840, and 1860) of second-gen prisons (Auburn System in blue, PA& #39;s Separate System in red).

Remember that PA& #39;s separate system was seen as dangerous to prisoners& #39; mental and physical health (among other problems--but this one played a big role).

And if you are interested in the larger context and historical narrative about how we overlooked early visible problems with prisons, including the Auburn System, you can watch my TEDx talk here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KPO3EkA__Xg">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

Curious about how disease is related to prison/jail reform more recently? Access to healthcare in prisons was the basis for some of the most important court cases recently. For this, see @JonathanSimon59& #39;s book, #MassIncarcerationOnTrial:

https://www.amazon.com/Mass-Incarceration-Trial-Remarkable-Decision/dp/1620972549">https://www.amazon.com/Mass-Inca...

https://www.amazon.com/Mass-Incarceration-Trial-Remarkable-Decision/dp/1620972549">https://www.amazon.com/Mass-Inca...

In a series of court cases leading up to Brown v. Plata, incarcerated plaintiffs and their atty& #39;s showed that (massive) overcrowding was preventing CA prisoners from getting any/adequate mental, physical, and dental healthcare.

Several cases ultimate were determined by the US Supreme Court in Brown v. Plata, which ultimately led to an agreement to take steps to reduce overcrowding by reducing the state& #39;s prison population.

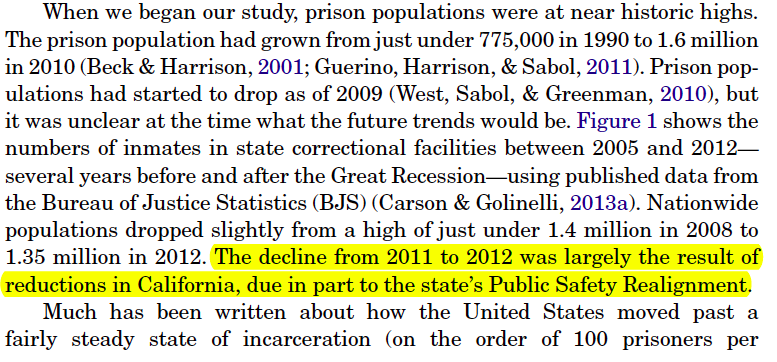

While a small percentage was ultimately released under realignment, bc CA& #39;s prison population is so big, the release of prisoners is actually why nationwide graphs of mass incarceration show a decline starting in 2012. S/o to #SusanTurner ( @UCIrvine) for this point.

So, in sum, disease and prison/jail reform has a long history. My take away is how differently we did things in the past. For all the inhumane treatment in the 18-19th Cs, their attention to prisons as total institutions with prisoners at the mercy of their keepers....

...and the way in which the physical and mental health of prisoners was a major consideration (one of several) in determining prison policy and practice, stands in contrast to much of what we see today.

And for further context, keep in mind that the stuff from 18th-19th C is when prisoners were officially not rights-bearing subjects. They were civilly dead. They could not officially sue prison admin for torture. Those rights came in the 1960s.

But despite their civil death, we still recognized their right to healthcare or at least the importance that we provided it. For them and for all of society.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter