Good morning, everyone. In today’s #BreakfastPaleography, we’re going back to basics: Paleography as literacy. Let’s learn how to read a script that can be particularly difficult because it is so different from today’s Roman alphabet letterforms. Let’s learn to read Beneventan!

Remember way back (as in yesterday) when I mentioned that many of the pre-Caroline minuscule scripts were localized? Beneventan is one of them. Developed and primarily used in southern Italy, Beneventan is unusual because it “survived” the 9th-c. Caroline-minuscule takeover.

First named by the great E. A. Lowe, Beneventan was thoroughly studied, and its exemplars tracked and catalogued, by the equally-great Virginia “Ginny” Brown, who regularly published handlists of known examples.

(n.b. Ginny Brown gave me this key to the Widener Library Medieval Studies reading room at Harvard 20ish years ago, and I still keep it on my keychain for inspiration even though it doesn’t open anything anymore.)

The earliest examples date from the 8th century. Rather than being supplanted by Caroline minuscule, Beneventan survived well into the 13th century and even spread across the Adriatic into Dalmatia. This script is both defiant and resilient!

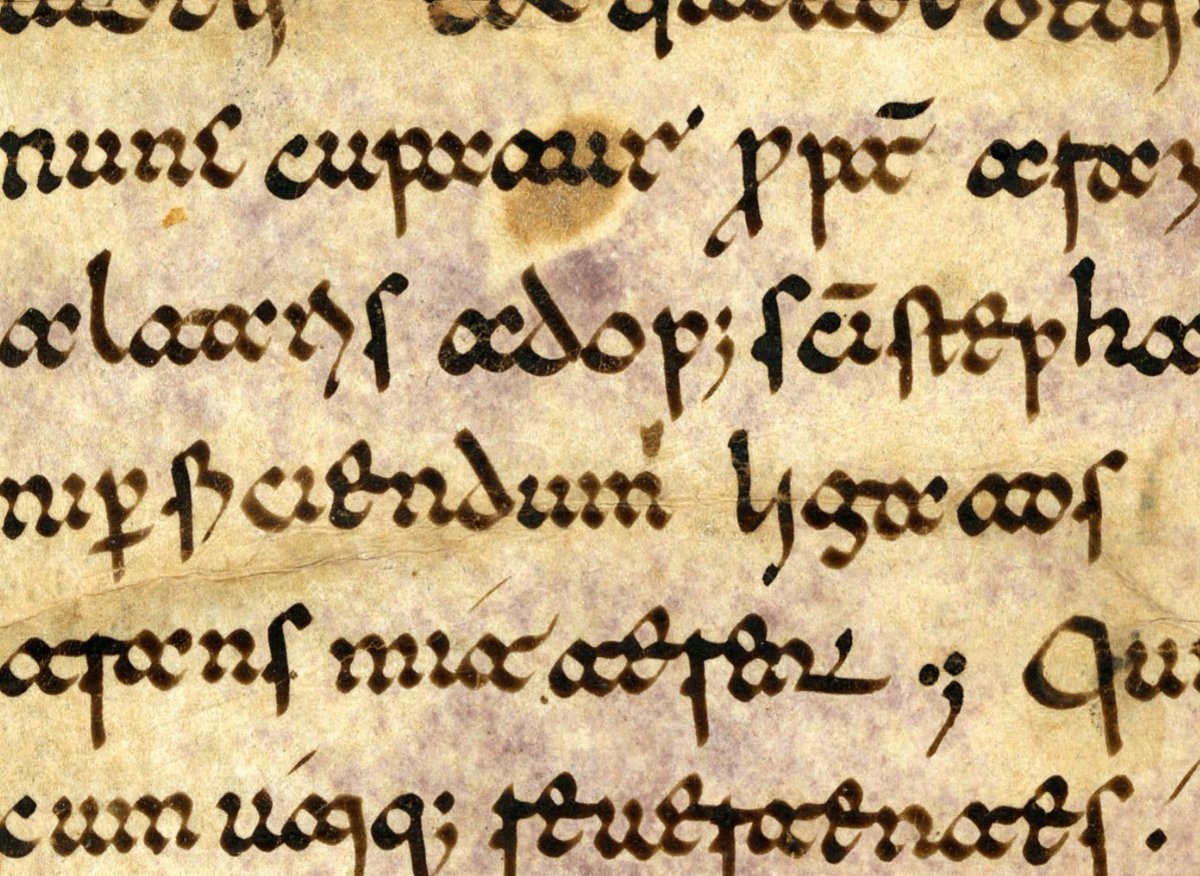

So now let’s learn how to read it. We’ll take a closer look at this s. XI 2/2 fragment from the Archivio di Stato in Frosinone, posted by @FragmentariumMS yesterday, catalogued there by @chiare13. https://fragmentarium.ms/view/page/F-tmy5/3432/35992">https://fragmentarium.ms/view/page...

The only way to learn to read Beneventan fluently is to unlearn how to read today’s Roman alphabet. Leave your preconceptions about what an [a] looks like, or an [r], or pretty much any other letter, at the door and learn to read from scratch.

One of the primary features of Beneventan is its minim. While the Caroline minim is a simple single stroke, the Beneventan minim is made up of two short thick strokes angling down and to the right. That’s what gives the script its “broken” and somewhat dizzying character.

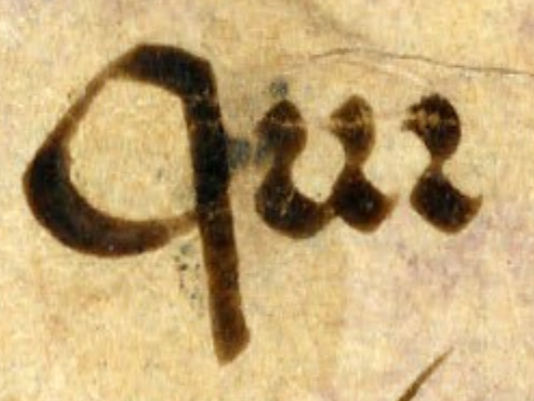

Another key to Beneventan is the distinction between [a] and [t]. Here’s the word “altaris.” If you look carefully at the [a] (red) and the [t] (blue), you’ll see one important difference: the stroke at the upper right. The [a]’s curves down, the [t]’s is horizontal.

The script uses several different forms of [r], depending on the context. Here are three: at the end of a word (red), in the middle of a word (blue), and ligated with [i] (green).

How& #39;d you do?

And now you can read Beneventan! If you want more, go to vHMML @visitHMML and practice! (scroll down to Exercise 2). Stay safe, friends! https://www.vhmmlschool.org/latin-visigothic-transcription">https://www.vhmmlschool.org/latin-vis...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter

![Another key to Beneventan is the distinction between [a] and [t]. Here’s the word “altaris.” If you look carefully at the [a] (red) and the [t] (blue), you’ll see one important difference: the stroke at the upper right. The [a]’s curves down, the [t]’s is horizontal. Another key to Beneventan is the distinction between [a] and [t]. Here’s the word “altaris.” If you look carefully at the [a] (red) and the [t] (blue), you’ll see one important difference: the stroke at the upper right. The [a]’s curves down, the [t]’s is horizontal.](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/EUrShwQU4AIggIN.jpg)

![The script uses several different forms of [r], depending on the context. Here are three: at the end of a word (red), in the middle of a word (blue), and ligated with [i] (green). The script uses several different forms of [r], depending on the context. Here are three: at the end of a word (red), in the middle of a word (blue), and ligated with [i] (green).](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/EUrS7J2UwAIaU5M.jpg)

![Another notable feature is the [e], which is really almost a majuscule. Another notable feature is the [e], which is really almost a majuscule.](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/EUrTEtKU0AAmad2.jpg)