From the Terner Center construction costs report:

If you control for the things we think should explain the rise in construction costs (labor and materials), the cost increase goes _up_ from $44/ft to $68/ft??

http://ternercenter.berkeley.edu/uploads/Hard_Construction_Costs_March_2020.pdf">https://ternercenter.berkeley.edu/uploads/H...

If you control for the things we think should explain the rise in construction costs (labor and materials), the cost increase goes _up_ from $44/ft to $68/ft??

http://ternercenter.berkeley.edu/uploads/Hard_Construction_Costs_March_2020.pdf">https://ternercenter.berkeley.edu/uploads/H...

Maybe this is bc of other regression controls, like metro area? So maybe the average hasn& #39;t gone up as much as the coefficient because of the (cheaper) Central Valley.

Or maybe it reflects an increase in fees? (though it& #39;s not obvious that fees increased in the last 10 years)

Or maybe it reflects an increase in fees? (though it& #39;s not obvious that fees increased in the last 10 years)

Unclear what the baseline is here (really depends on which metros get their own dummy variables vs. get considered the "default" group), but this seems bad.

They find that affordable housing is not more expensive than market-rate/mixed-income projects when you control for project size. This is pretty surprising.

I& #39;m also confused by the last sentence—I thought hard costs usually go _up_ as project size increases?

I& #39;m also confused by the last sentence—I thought hard costs usually go _up_ as project size increases?

BTW, if you want to learn about who Don Terner was (founder of BRIDGE Housing, and inventor of California& #39;s unique model of building publicly-funded housing while circumventing Article 34), go read Golden Gates!

This is really interesting: when you break it down by component (each includes both materials and labor), concrete has mostly stayed flat, while wood/plastics and finishings went up significantly.

Their theory about finishings is exciting because it suggests that any decrease in non-hard costs—i.e. cheaper land or faster predictable permitting—could cause hard costs to go down simply by allowing developers to target less luxury tenants!

(Unfortunately they don& #39;t say what fraction of costs are from finishing, so it& #39;s not clear how large this reduction would be overall)

The labor market for construction workers makes no sense. Workers are hard to find, but wages are flat from 2006 to today. Shouldn& #39;t developers be paying more to avoid costly delays from not finding workers?

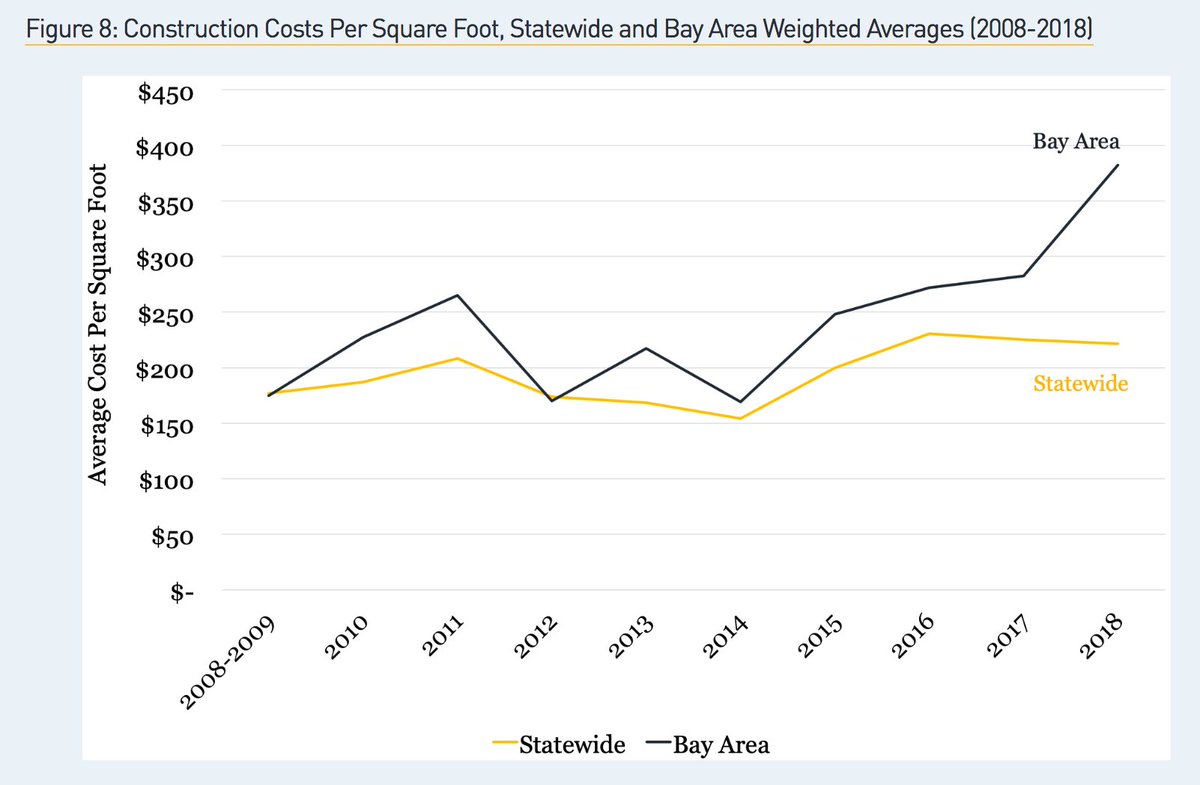

One confusing thing here is that their construction costs numbers only go back to 2008-2009, but IMO it doesn& #39;t make sense to compare costs to the trough of the recession. Maybe the drop in the number of projects in 2008-09 explains why hard costs were so cheap then?

i.e. maybe costs were also high in 2004-2007 before the labor force caught up to the increased demand for workers? And maybe that can happen again this decade (since multifamily permits have been going up recently)?

(well, ignoring the recession we seem to be getting into :( )

(well, ignoring the recession we seem to be getting into :( )

So where is the money actually going, if not to workers? Apparently general contractors and subcontractors are taking higher margins, to hedge against the risk of their workers leaving.

Why don& #39;t they just give that money to workers to make sure they don& #39;t leave??

Why don& #39;t they just give that money to workers to make sure they don& #39;t leave??

Their estimate of the cost of prevailing wage requirements—$30/sq ft—is very high, much higher than the numbers I& #39;ve seen Scott Littlehale post.

Though it& #39;s also possible that in central cities where prevailing wage is required, wages would be higher anyways

Though it& #39;s also possible that in central cities where prevailing wage is required, wages would be higher anyways

Here& #39;s a catch with the wage numbers. Though worker wages in all of California (adjusted for national inflation) are generally flat, in the Bay Area real wages adjusted for national inflation are actually up. So the "worker shortage" theory DOES make sense in the Bay Area

I had no idea that SF requires "air quality ventilators" in new buildings. My friend who lives in a new-ish building (788 Harrison) doesn& #39;t have A/C, FWIW

I& #39;ve heard mostly pessimistic things about modular, but Terner claims they& #39;ve found that it cuts costs by 20% and project timelines by 40-50%.

Unclear if that 20% is hard costs only, or also includes the other savings caused by the 40-50% speedup

Unclear if that 20% is hard costs only, or also includes the other savings caused by the 40-50% speedup

Mass timber stalled in the State Assembly in 2019, but maybe it could be back this year??

Hadn& #39;t seen the seismic argument for mass timber before: because it& #39;s lighter than concrete/glass, it& #39;s cheaper to earthquake-proof a MT building than a regular mid/high-rise

Hadn& #39;t seen the seismic argument for mass timber before: because it& #39;s lighter than concrete/glass, it& #39;s cheaper to earthquake-proof a MT building than a regular mid/high-rise

Here& #39;s the full regression results btw. I& #39;m very unsure about this question of whether affordable housing is more expensive or not, given the effect is p<0.01 but then becomes p>0.10 when you add in project size.

I& #39;m also unsure about the "economies of scale" of project units. Affordable projects being mostly small could be causing that coefficient to appear significant

One way to tease this out could be to regress on just market-rate projects and see if project size is still significant

One way to tease this out could be to regress on just market-rate projects and see if project size is still significant

(Also, props to them for using mostly dummy variables rather than continuous variables in their regression. But they messed up with project size... adding dummy variables for buckets would be better, or maybe using log(project size) or something)

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter