This week in Network Epistemology we talked about a philosophical problem called "testimony" and its connection with homophily.

The basic question: what are the effects of different strategies for trusting others?

The basic question: what are the effects of different strategies for trusting others?

In philosophy, there are two basic approaches to testimony. One says that you should trust others for the same reason that you trust scientific instruments, because they are usually reliable. The other view says that people are special and you ought to trust them by default.

The debate in philosophy mostly asks this question: what justifies you believing something that you& #39;re told? But, in class today, we focused on a different question: what are the consequences of adopting these strategies for a community?

For those interested, here& #39;s a nice introduction to the way traditional philosophers approach the problem. (Fair warning, some of this will seem very strange to a social scientist.)

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/testimony-episprob/">https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/t...

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/testimony-episprob/">https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/t...

We started with this paper by Mayo Wilson. He looks at how scientific results are communicated by non-specialists. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11229-013-0320-2">https://link.springer.com/article/1...

He asks two questions:

(1) How should non-experts solicit opinions on scientific matters?

(2) How should communication networks be structured?

(1) How should non-experts solicit opinions on scientific matters?

(2) How should communication networks be structured?

No terribly surprisingly, he finds that lay people do better when they seek out those who are "closer" to experts in the social network. If you can& #39;t find an expert it& #39;s better to find an approximate expert.

On the social network side, he finds an interesting trade-off. Networks where specialists communicate more with one another are faster at coming to true conclusions but, also, they result in higher error among non-specialists.

Put more succinctly: If we want a well informed community, that may come at the cost of the rate of scientific discovery.

The second paper we read is a model I devised to engage with the philosophical literature on testimony.

The basic question: from a community perspective, does a group do better when its members try to seek out the "more reliable" members? https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11098-014-0416-7">https://link.springer.com/article/1...

The basic question: from a community perspective, does a group do better when its members try to seek out the "more reliable" members? https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11098-014-0416-7">https://link.springer.com/article/1...

It turns out the answer to this question is a little complicated. First, we have to distinguish between two senses of better. On one, a group does better when it has fewer false beliefs. On another, a group does better when it has more true beliefs. These two often conflict.

We also have to ask how people find who& #39;s "more reliable." Most of the time this is done by judging what you believe relative to what I believe. This is all fine and good if I& #39;m right, but if most of my beliefs are false, I& #39;m going to find other unreliable people trustworthy.

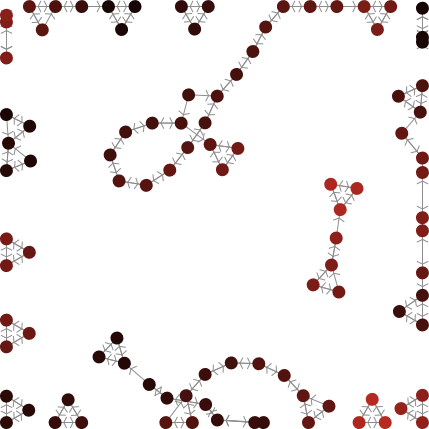

And the model shows this. When people try to seek out the more trustworthy the network segregates into very reliable groups and very unreliable groups (red = bad, black = good).

Also seeking our reliable individuals can be harmful because it reduces the total amount of information you can collect: it makes the network overly clustered. As a result, seeking out the more reliable can actually reduce how much knowledge exists in the community.

So, somewhat paradoxically, I argue, communities might do better when it individuals are less sensitive to the reliability of their sources. (A very counter-intuitive conclusion in the modern world.)

In class, we discussed many of the assumptions of these models. Especially we focused on the "qualitative belief" framework, where people& #39;s beliefs are represented by a simple three-place relation: believe, disbelieve, or suspend judgment.

There is some legitimate concern that some of the underlying questions and approaches might not be translatable to richer environments with probabilistic beliefs or where people are reasoning and arguing (our topic in a few weeks).

We also discussed how these particular models do and don& #39;t engage with the older philosophical discussion of testimony.

Overall, the class was an interesting discussion at the boundary of social science and philosophy. Although, the general consensus was that the area needed more models and more exploration of some of the conclusions.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter