The Byzantines often tried to assimilate barbarians by resettling groups of them in other parts of the empire. But this worked at cross-purposes to another desire: to use the barbarians’ unique military talents in service to the army.

~BE

https://twitter.com/Tweetistorian/status/1245388321888653317

https://twitter.com/Tweetisto... href="https://twtext.com//hashtag/Twittistorian"> #Twittistorian

~BE

https://twitter.com/Tweetistorian/status/1245388321888653317

The Slavs resettled in Anatolia retained their identity for several centuries, serving as specialized troops. So too the Gothogreeks: presumably the mixed descendants of the Goths serving in the 5th-century army, they formed a distinct military unit 300 years later.

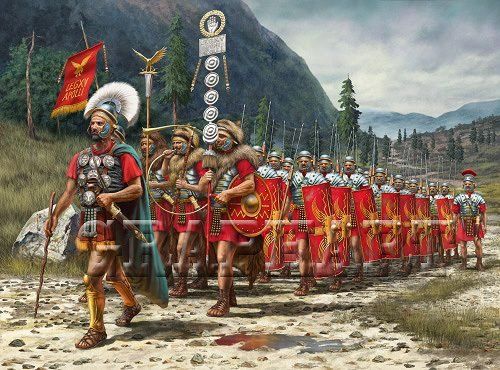

The use of specialized barbarian troops to fight other barbarians on the frontier was an old Roman practice, dating back to the foederati of the 4th century.

But Rome was always much stronger than the barbarians. How did this work when Byzantium was faced with stronger enemies?

But Rome was always much stronger than the barbarians. How did this work when Byzantium was faced with stronger enemies?

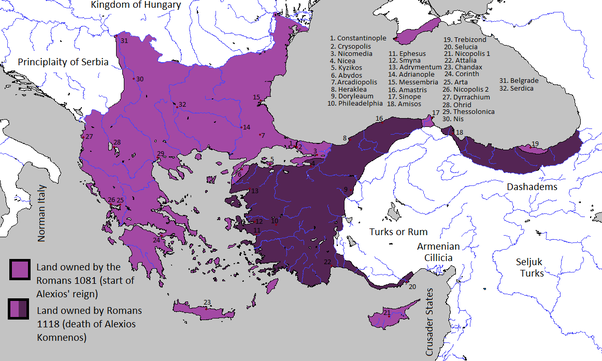

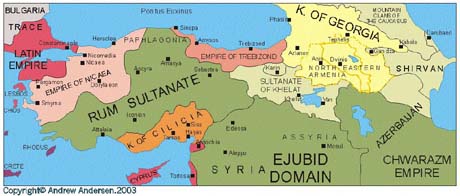

The two foreign powers that dealt Byzantium its most devastating blows were the Seljuk Turks (Manzikert, 1071) and the Venetians (Sack of Constantinople, 1204). After their victories, they occupied Byzantine lands for some time after.

Human nature being what it is, the conquerors often married local women and adopted local customs—in the case of the Turks, sometimes converting to Christianity. These unions produced two of the most interesting examples of foreign troops: Turcopoles and Gasmouloi.

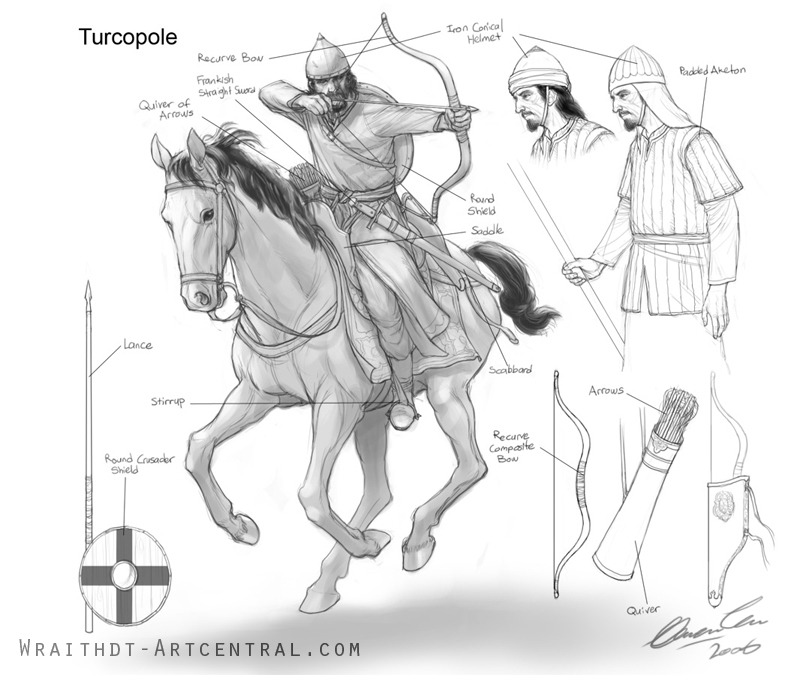

The Turcopoles (“sons of Turks”) were soldiers who fought in the Turkish manner, having learned to it from their fathers even as they shared their mothers’ loyalties. They served as light cavalry in the Byzantine army during the post-Manzikert Comnenian reconquest of Anatolia.

The Gasmouloi were sons of Venetians settled in Constantinople following the Fourth Crusade who had married Greek women. They learned seacraft from their fathers and, following the Byzantine recapture of Constantinople in 1261, enlisted in the navy as marines.

Like all barbarians and semi-barbarians, Turcopoles and Gasmouloi were thought to be questionably loyal, born into Byzantine culture though they were. Venice and the Seljuks were still great threats, using mixed troops was a necessary risk to lessen these enemies’ advantages.

Besides, centuries of constant warfare had taught the Byzantines a hard lesson: resettled foreigners often rebelled or defected. Armenians settled in Cilicia even established an independent kingdom as soon as Byzantine power weakened after Manzikert.

Ultimately, these foreign troops could never be more than a temporary expedient. Byzantium’s genius was in managing difficult problems, but it lacked the strength to decisively solve them—Byzantine armies never dominated battlefields as surely as the legions of earlier Rome.

If anything, Byzantium’s great strength was the cohesion of its people, which kept it together through many difficult centuries. An increasing reliance on foreign or semi-foreign mercenaries was a sign of growing weakness. Tomorrow we’ll look at why this was.

~BE

#Twittistorian

~BE

#Twittistorian

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter