Sobering news: for the past month, @LizAnanat and @agpines have been collecting daily surveys with low-wage workers with young children. They didn’t plan to study the COVID crisis, but their results show how it is unfolding and how policy has not yet softened its blow. 1/17

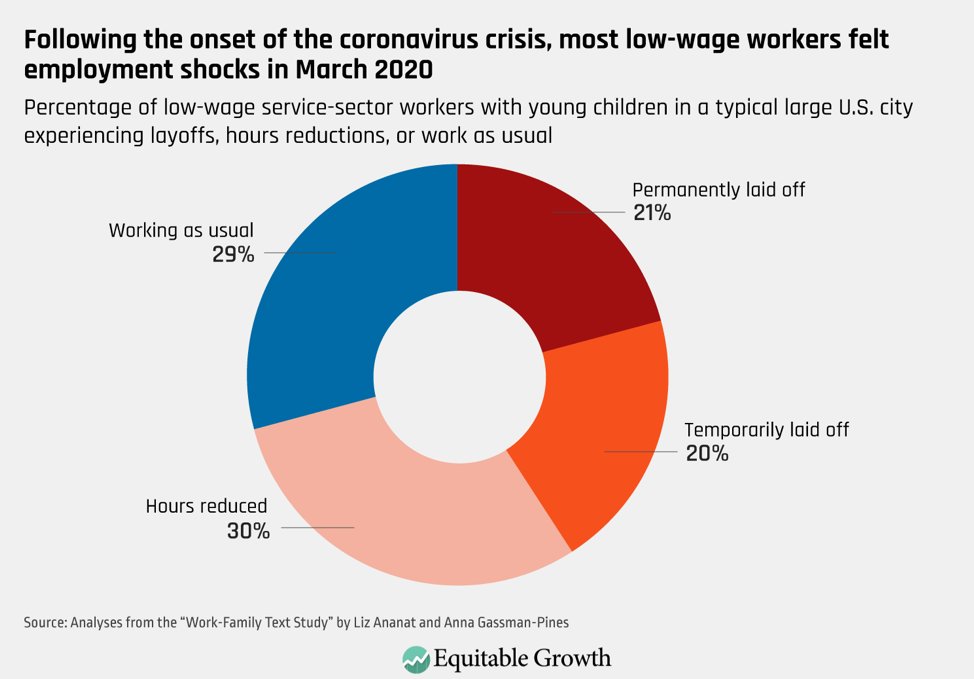

Following the onset of the coronavirus crisis, more than two-thirds of the workers surveyed found themselves working less, with more than 40 percent experiencing layoffs. 2/17

As work hours dwindled, parents slept poorly. They reported feeling fretful, angry, irritable, anxious, or depressed all day long. Their children increasingly demonstrated uncooperative behavior. 3/17

The experience of parents and their children is deeply intertwined. As parents’ moods suffered, they reported that their young sons and daughters demonstrated uncooperative behavior, which, for children, is a harbinger of deeper psychological distress. 4/17

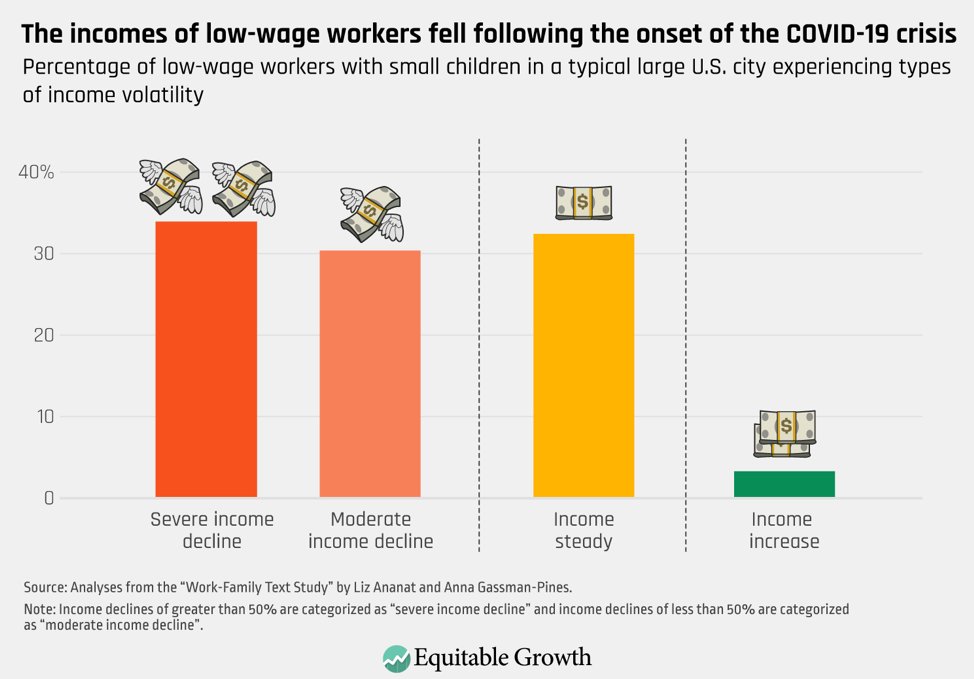

Decreases in work hours are accompanied by falls in income. Nearly two-thirds of respondents reported that their income fell following the onset of the coronavirus crisis. 5/17

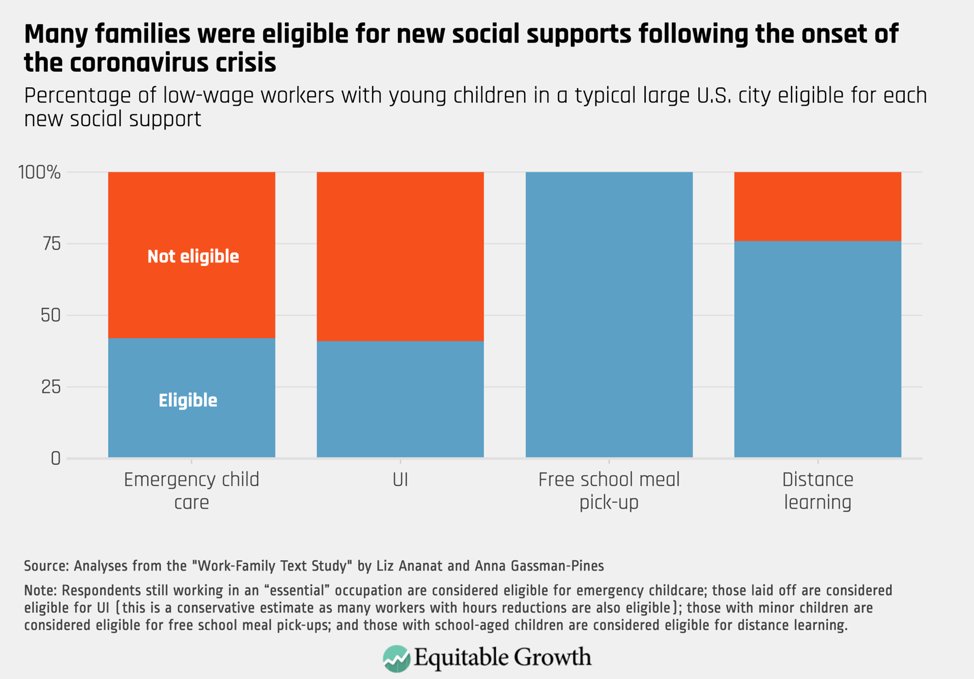

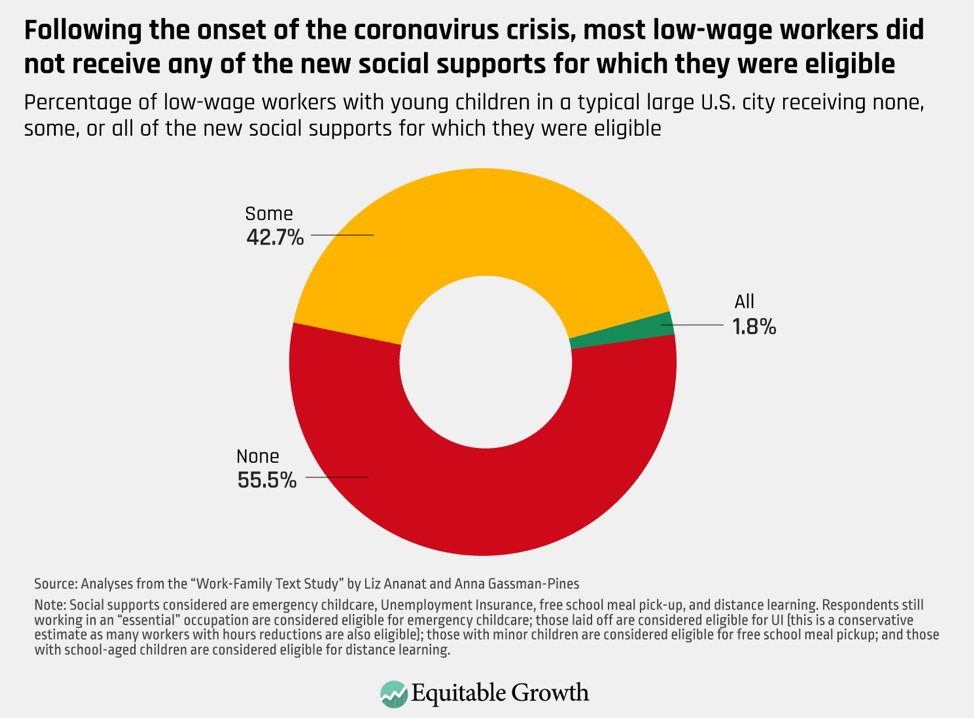

Policymakers anticipated the hardship and acted. They made emergency childcare available for essential workers and UI available for those who were laid off or had hours reduced. They provided free meals for all kids, and distance learning for those with shuttered classrooms. 6/17

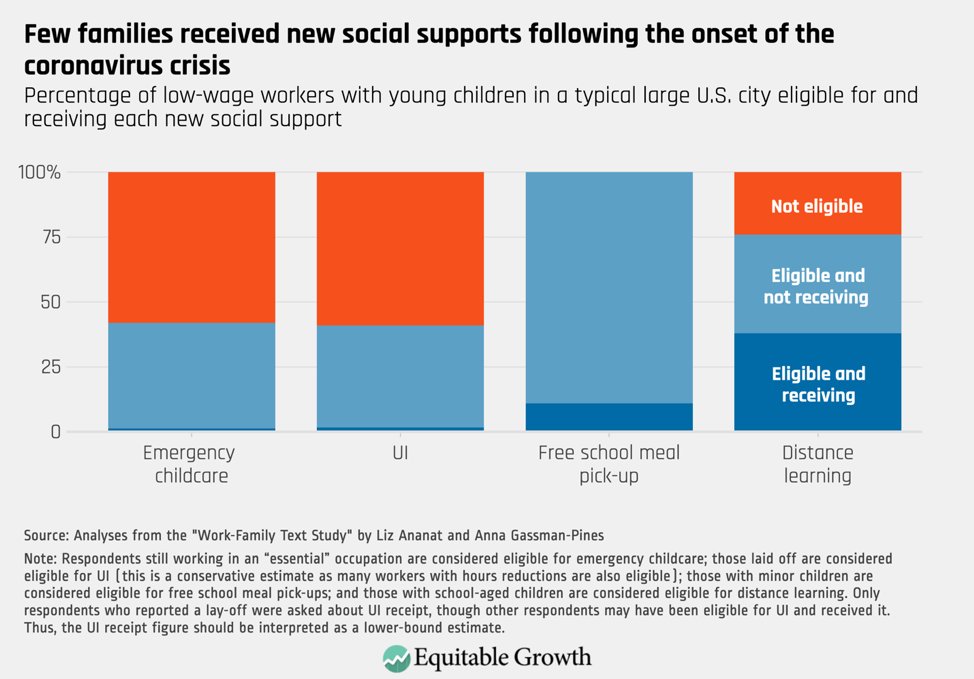

Yet, few families accessed them. Although 45% of laid-off respondents had applied for Unemployment Insurance, just 4% had received it at the time of the survey. 8/17

Indeed, more than half of these low-wage workers did not receive any of the services for which their families were eligible. 9/17

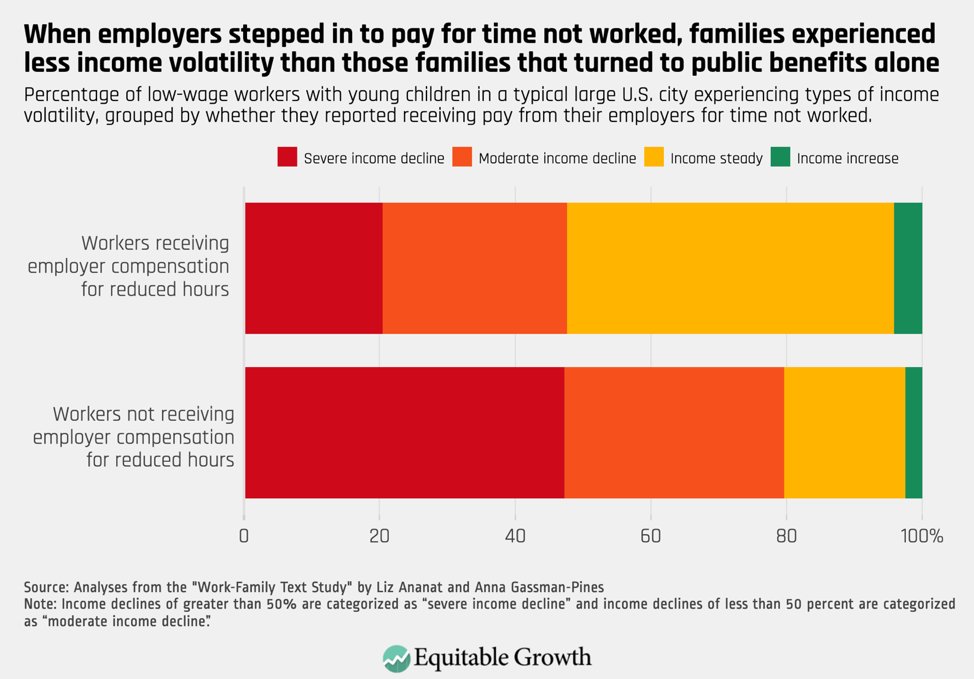

Though public benefits did not reach low-wage workers in the first weeks of the crisis, those who received compensation from their employers for their reduced hours experienced less income volatility than their peers who had to rely on the public safety net alone. 10/17

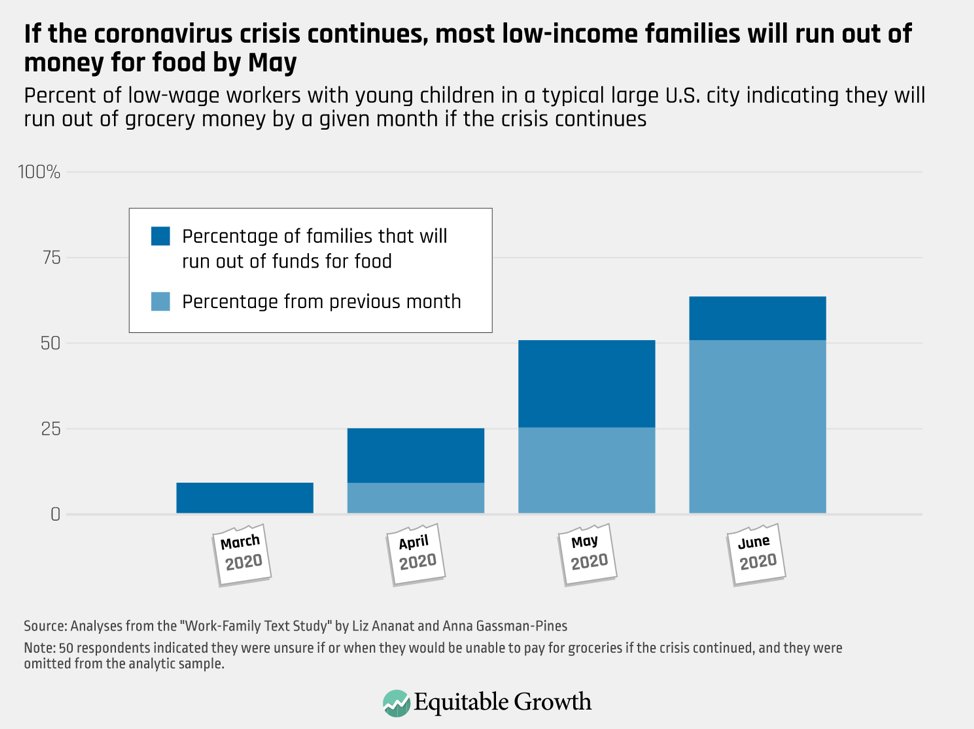

Taking stock of these serious financial challenges facing families, the research team asked respondents, “If the crisis continues, for how many months do you think you will be able to pay for groceries?” 11/17

Of those respondents who were able to provide a guess, nearly 1 in 10 predicted running out of money for groceries during the week of the survey, and half predicted not being able to pay for groceries sometime before the end of May. 12/17

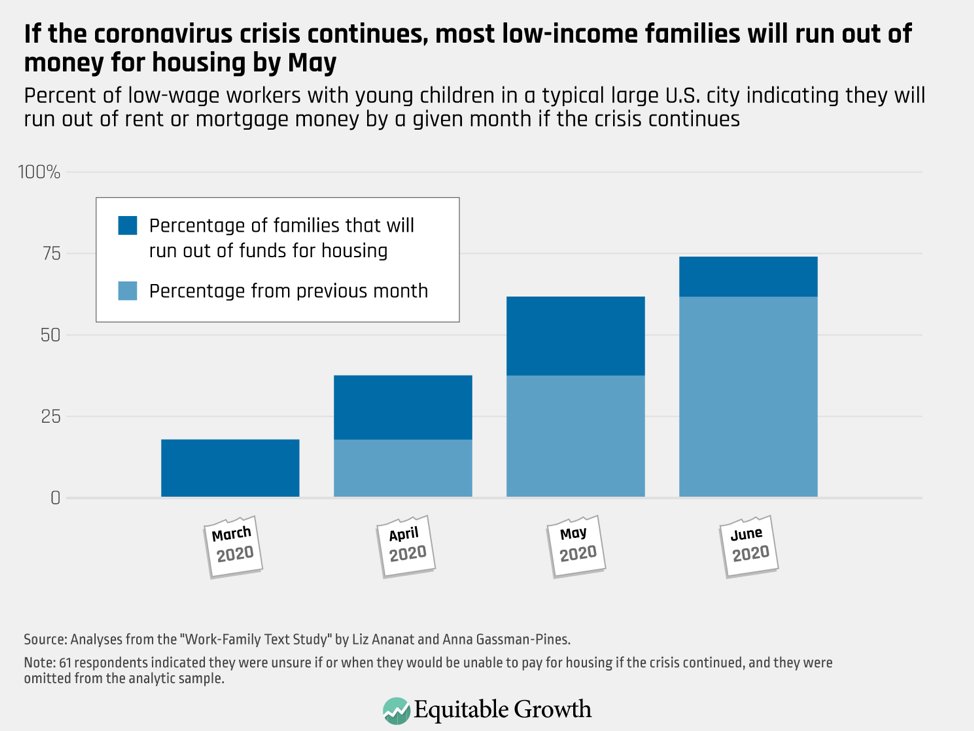

Similarly, the low-wage workers who were surveyed predict that if the crisis continues, they’ll be unable to pay for housing. Nearly 1 in 5 predict running out of rent money during the survey week, and three-quarters predict running out sometime before the end of June. 13/17

So what do we do? Over the past several weeks, policymakers have recognized that low-income families are suffering and have stepped up to provide support. But benefits won’t ameliorate the distress of families—or stabilize the economy—if workers don’t access them. 14/17

We should do several things. The researchers behind the study make the smart point that if benefits reach workers most quickly when delivered by the employer, legislation should require (and help) more employers to funnel resources to workers. 15/17 https://econofact.org/snapshot-of-the-covid-crisis-impact-on-working-families">https://econofact.org/snapshot-...

Next, policymakers have overlooked a key vehicle for stabilizing incomes: SNAP. Half of workers in this sample were receiving SNAP before the crisis hit. If we increase SNAP benefits, money will reach these workers automatically and efficiently. 16/17 https://www.cbpp.org/blog/latest-coronavirus-response-package-doesnt-boost-snap-the-next-one-should">https://www.cbpp.org/blog/late...

Finally, it’s crucial to increase outreach efforts and reduce red tape so that we all know that help exists and can access it. The COVID crisis has harmed working families and policy has yet to soften the blow. We can still change course and help those who need it most. 17/17

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter