For those following the interest in hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil) for COVID-19, here is a brief review of what is known of the drug& #39;s neuropsychiatric adverse effect profile, particularly as compared to that of other quinoline antimalarials, such as chloroquine.

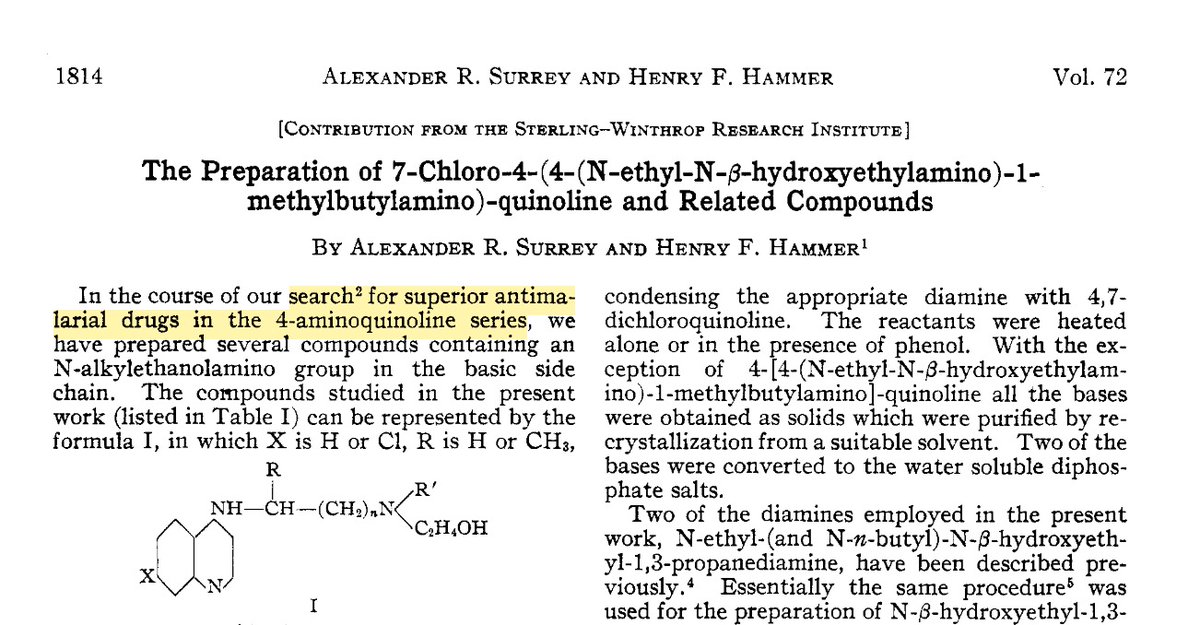

The synthesis of hydroxychloroquine was first reported by Surrey and Hammer in 1950, as part of an effort to develop an antimalarial drug "superior" to chloroquine, a drug which had itself been rediscovered during an urgent WWII-era drug discovery program.

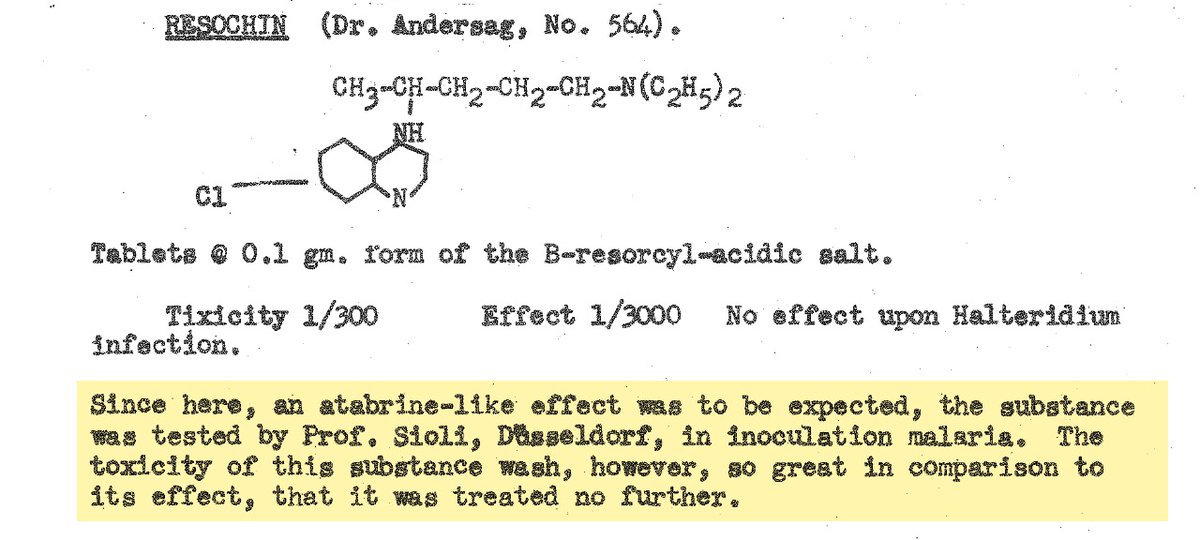

The adverse neuropsychiatric effects of chloroquine are a subject for another thread. However, of note here, despite having first synthesized the drug years earlier (as "resochin"), the Germans had abandoned it, having initially declared it too toxic for human use.

The "atabrine-like" effect referred to in the previous WWII-era U.S. military intelligence report (itself based on captured German military research documents) was a reference to the neuropsychiatric adverse effects of the drug that chloroquine largely replaced following the war.

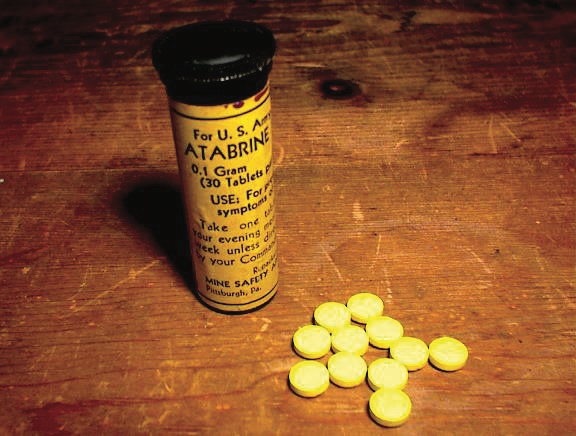

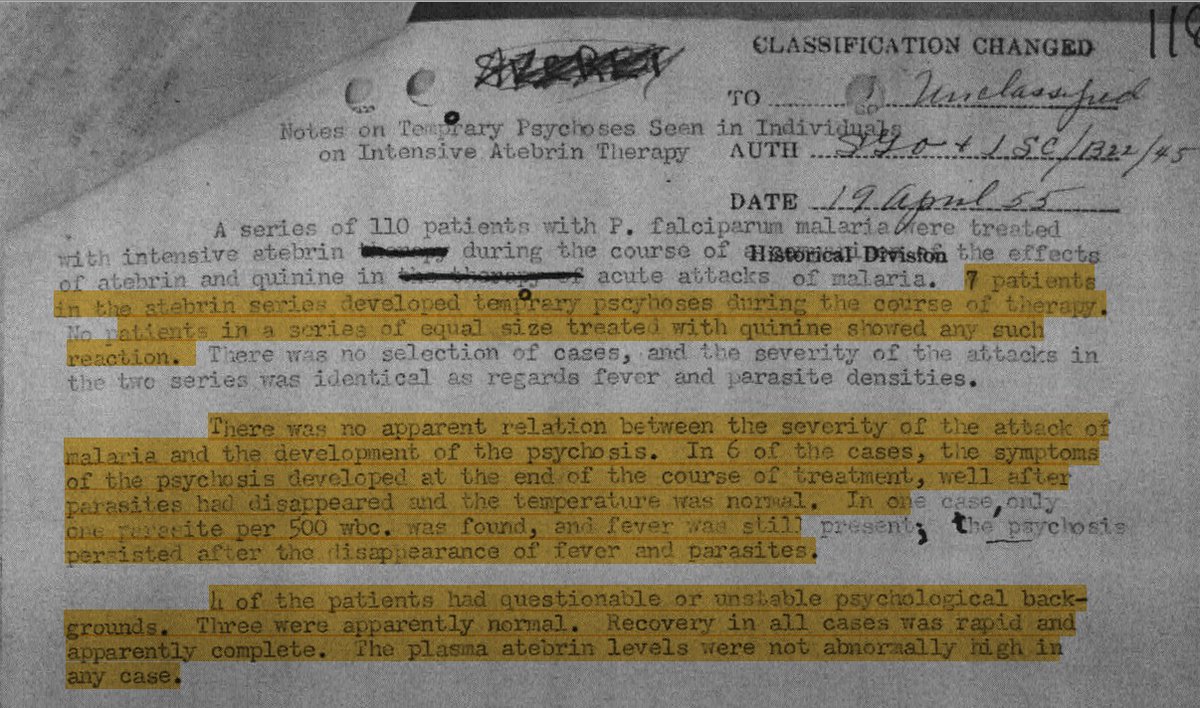

The U.S. rediscovered chloroquine primarily because the ring-substituted quinoline quinacrine (Atabrine)–then our our primary prophylactic antimalarial–caused toxic psychoses. This fact was classified as "restricted" and not widely disclosed as a matter of national security.

Following the war, a remarkable period of open, and apparently censorship-free publication provided a glimpse of the U.S. military& #39;s knowledge of the frequency of these reactions among combat deployed personnel.

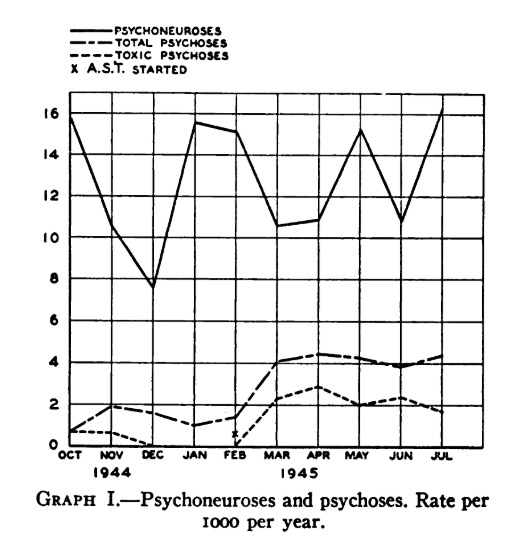

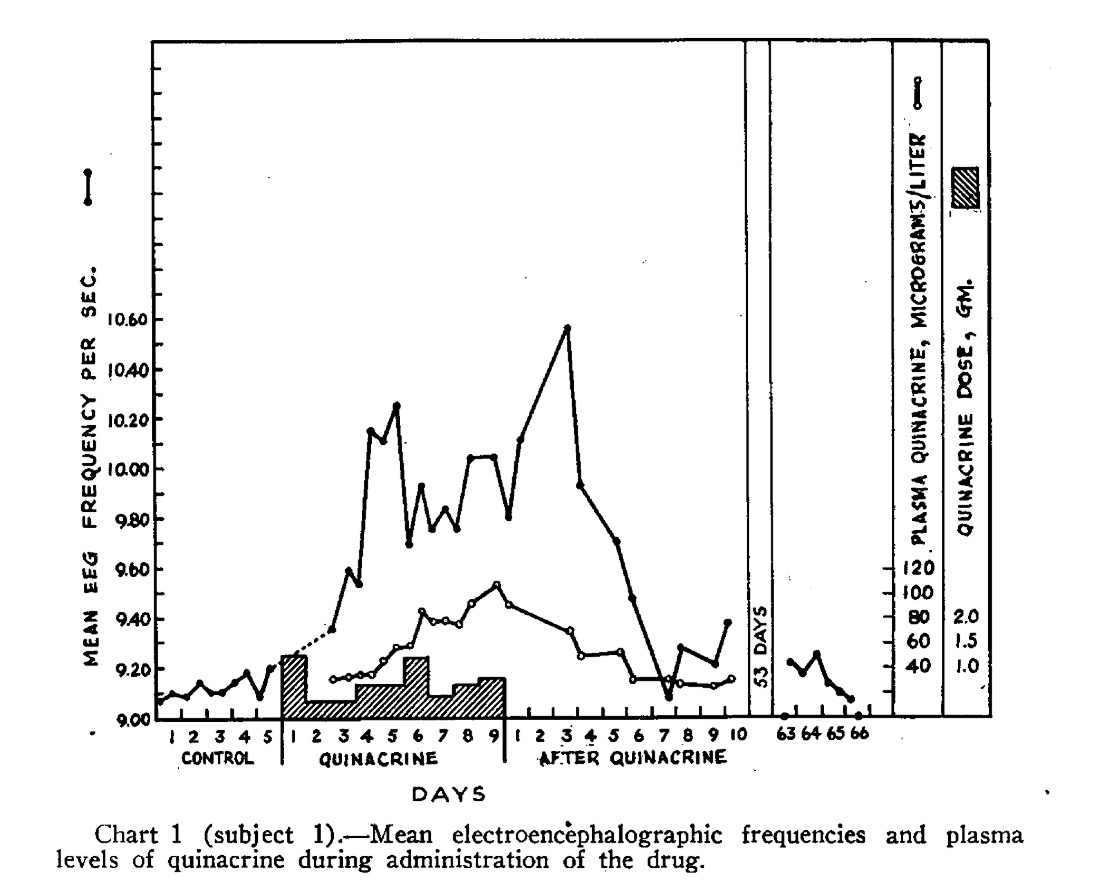

Among the most remarkable publications was one which included this graph, demonstrating a clear increase in the rate of toxic psychoses upon initiation of antimalarial prophylaxis with quinacrine – approximately 2 per 1,000 per year.

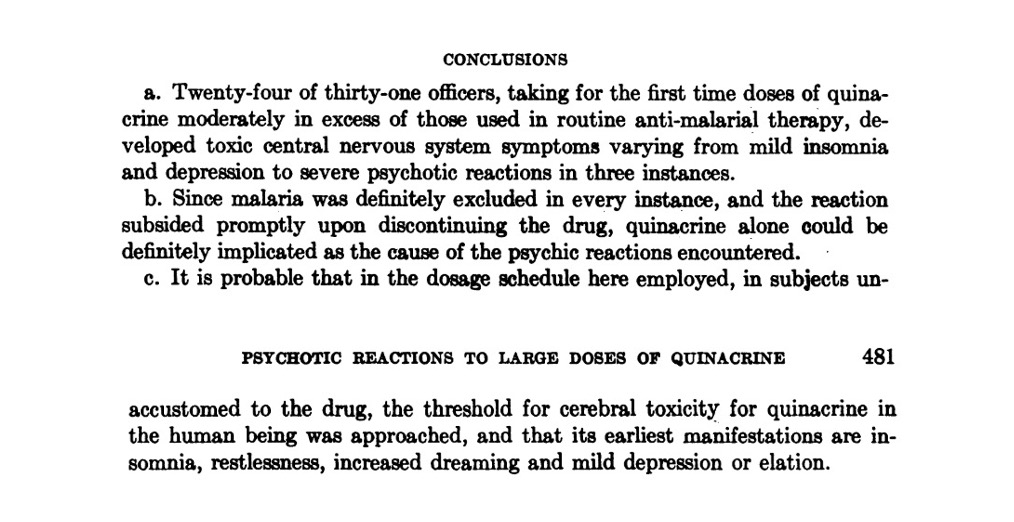

In a final remarkable paper, the outcome of a trial of quinacrine (Atabrine) on healthy U.S. Army medical officers was published in 1947. These conclusions speak for themselves. Note the "earliest manifestations" of insomnia, abnormal dreams, etc. described in the final sentence.

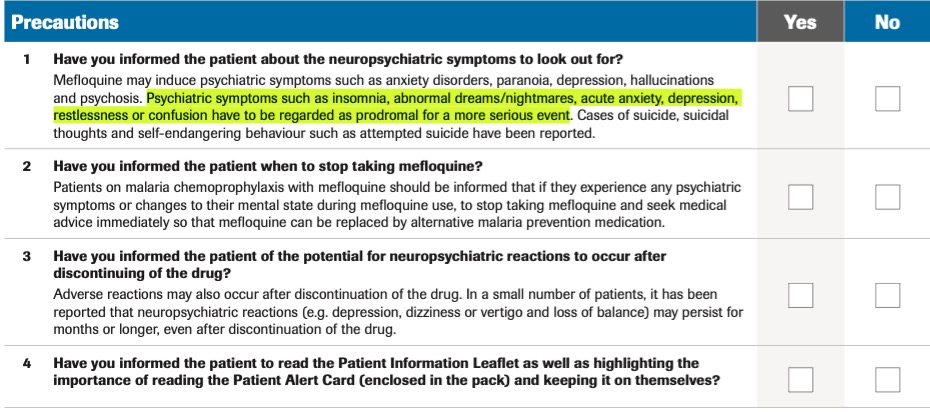

These very same symptoms would go on to inform the warnings for use of a later antimalarial quinoline, mefloquine (Lariam). Users are warned to immediately discontinue the drug at the onset of such symptoms, which "have to be regarded as prodromal for a more serious event".

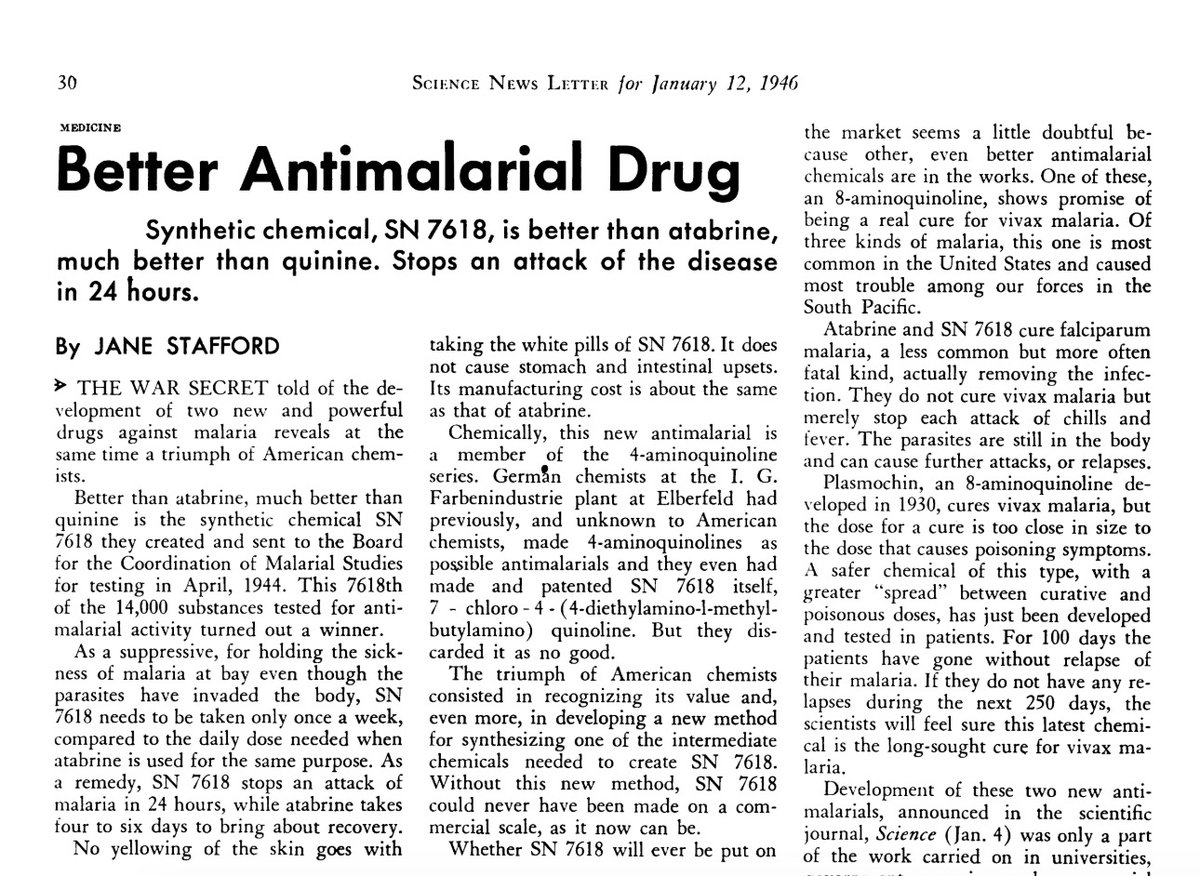

But back to chloroquine. Towards the end of WWII, a decision was made by senior leadership to prioritize this drug (then known as SN 7618) for development as a replacement for quinacrine (Atabrine), and it soon became the U.S. military& #39;s drug of choice, remaining so for decades.

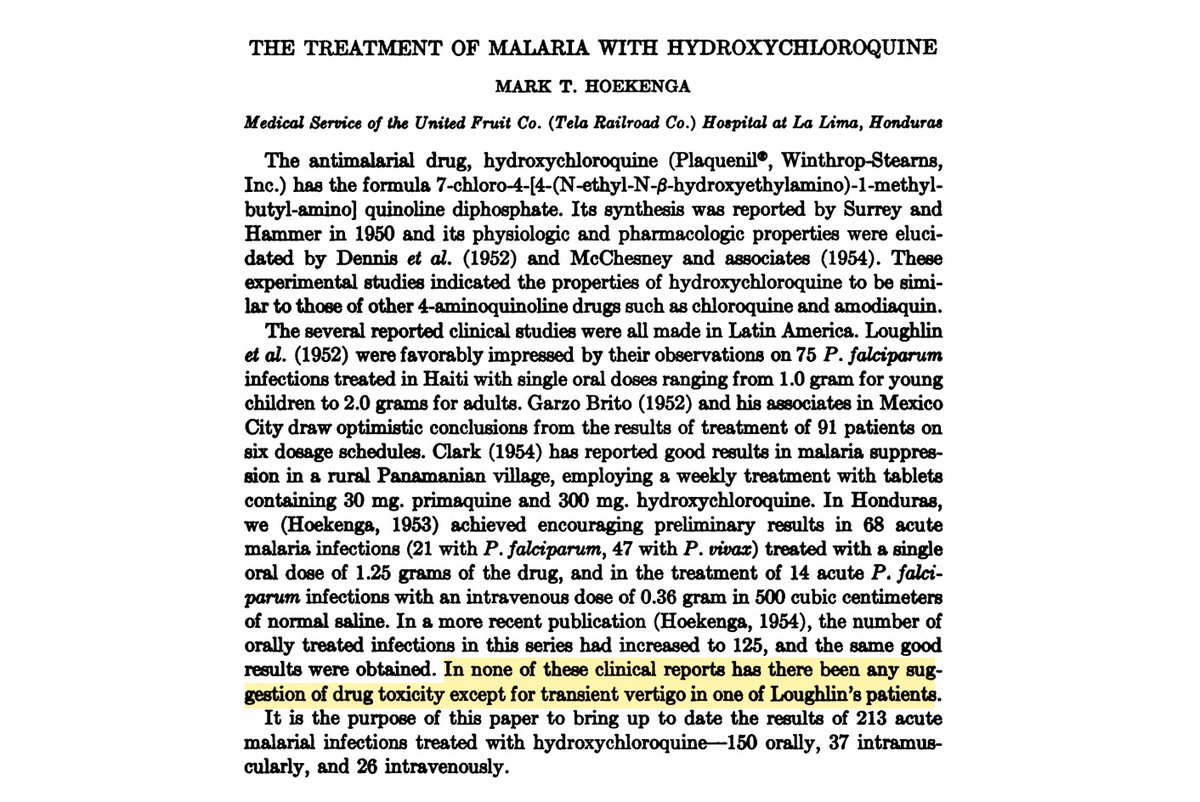

Despite being described as having "low toxicity", the problems with chloroquine were well-known, and efforts were soon underway to synthesize safer and better-tolerated alternatives, including hydroxychloroquine, which was soon put into testing/use in plantations in the Americas.

Although chloroquine continued to be described as "safe" the interest in hydroxychloroquine appears to have been primarily based on its perceived improved tolerability, itself based mostly on the subjective impressions of the plantation medical officers overseeing these "tests".

Recall that the primary concerns motivating the switch from quinacrine (Atabrine) to chloroquine and then to hydroxychloroquine were concerns of serious neuropsychiatric adverse effects including psychosis, whose early warning signs were often subtle symtoms such as insomnia.

It is a question worth exploring, whether the third-world plantation workers on whom hydroxychloroquine was first widely trialed, would report these and other neuropsychiatric symptoms, or even attribute these or more serious symptoms such as psychosis to the drug.

By 1955 enough experience had been gathered from such trials for FDA to approve hydroxychloroquine as Plaquenil–but being thought less effective than chloroquine, interest soon began to wane for its use as an antimalarial. The drug& #39;s salvation would come from an unlikely source.

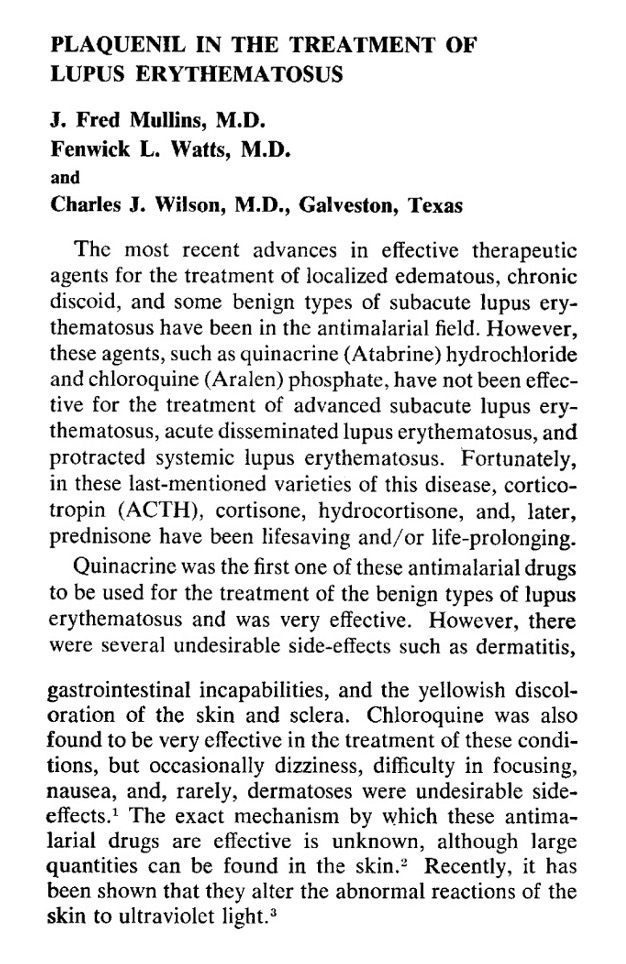

The rheumatology community had found that the earlier drug quinacrine–which caused toxic psychoses–was highly effective against several disorders but was too poorly tolerated to be of widespread use. Interest naturally turned to hydroxychlorquine after its FDA licensing in 1955.

Beginning in the late 1950s, hydroxychloquine became more widely used in the treatment of various rheumatologic disorders. Its perceived effectiveness for this indication and its perceived tolerability were mostly based on anecdote and observational open-label comparison studies.

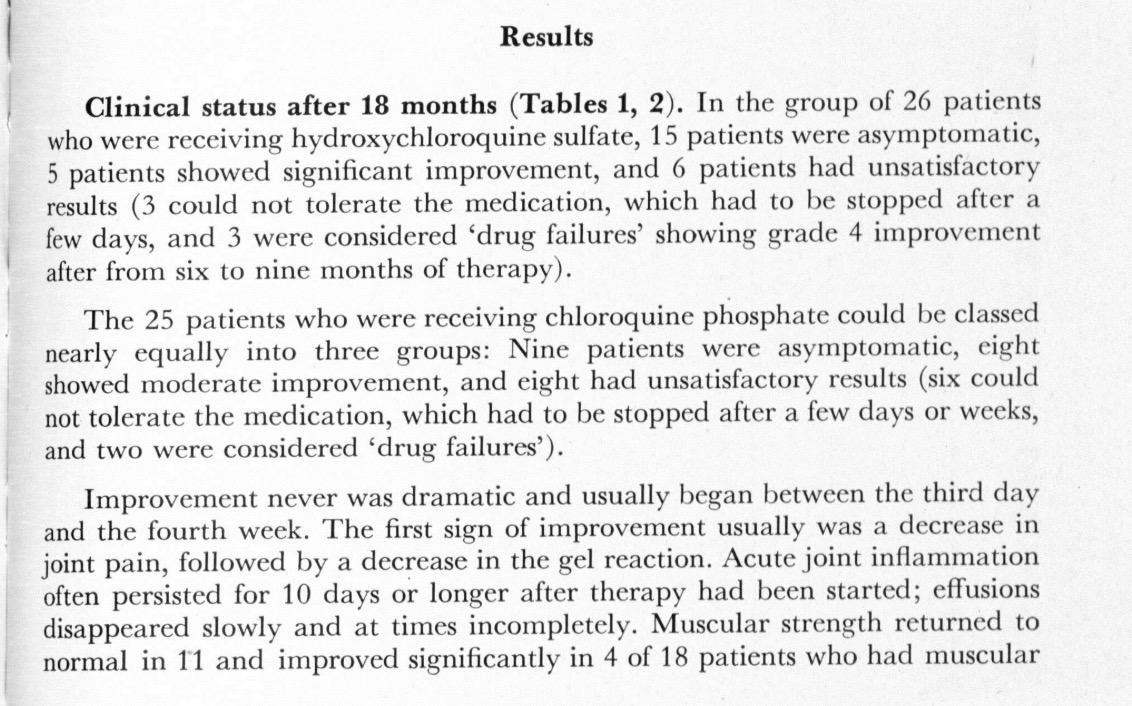

Here is an example of such a study. A fairly consistent finding is that somewhere on the order of 10% of patients simply could not tolerate hydroxychloroquine, almost always early during use. The reasons for this were not always carefully explored.

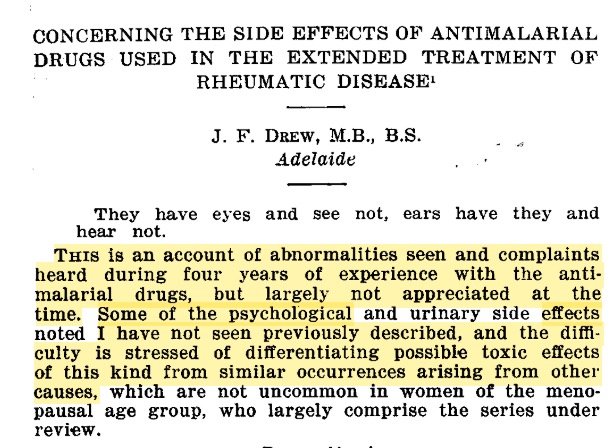

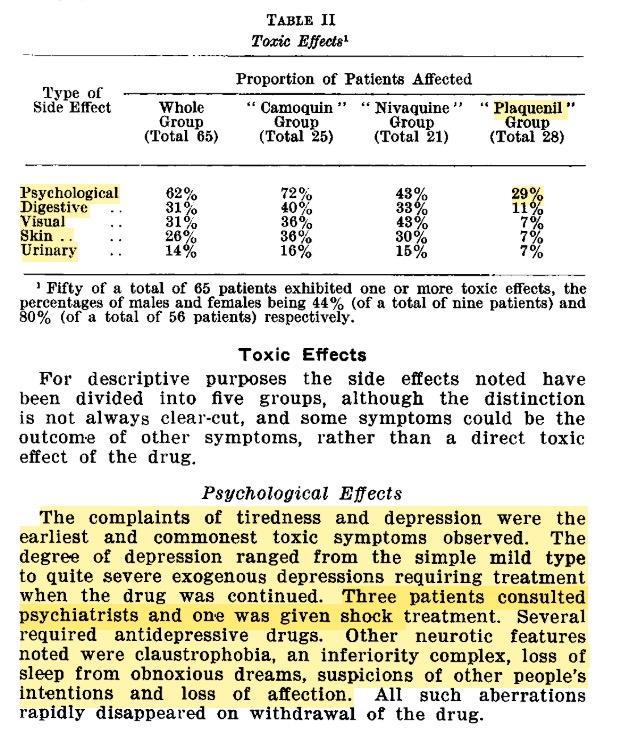

The first attempt to describe the neuropsychiatric adverse effect profile of hydroxychloroquine appears to have been published by Drew in 1962. His paper alludes to the fact that many of these adverse effects were "largely not appreciated at the time".

Although not rigorous by today& #39;s standards, his observations are telling for the similarities of the reported neuropsychiatric symptoms with those reported from the earlier drug quinacrine (Atabrine)–for which chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine were considered safer replacements.

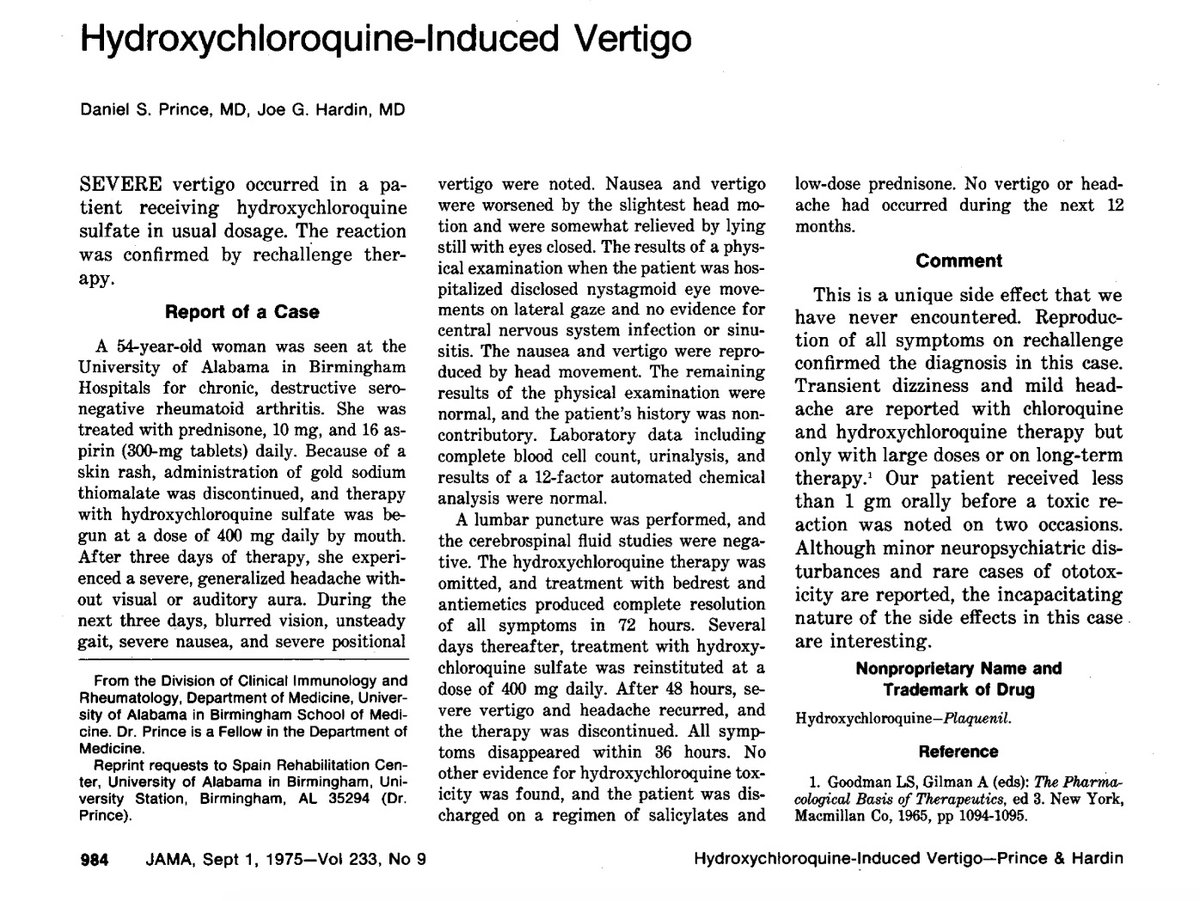

A brief discussion of purely neurologic effects: recall an earlier paper referenced complaints of vertigo with use hydroxychloroquine. Some years after its FDA licensing, a clear causal case of what appears to be central (i.e. brainstem) vertigo was later reported from the drug.

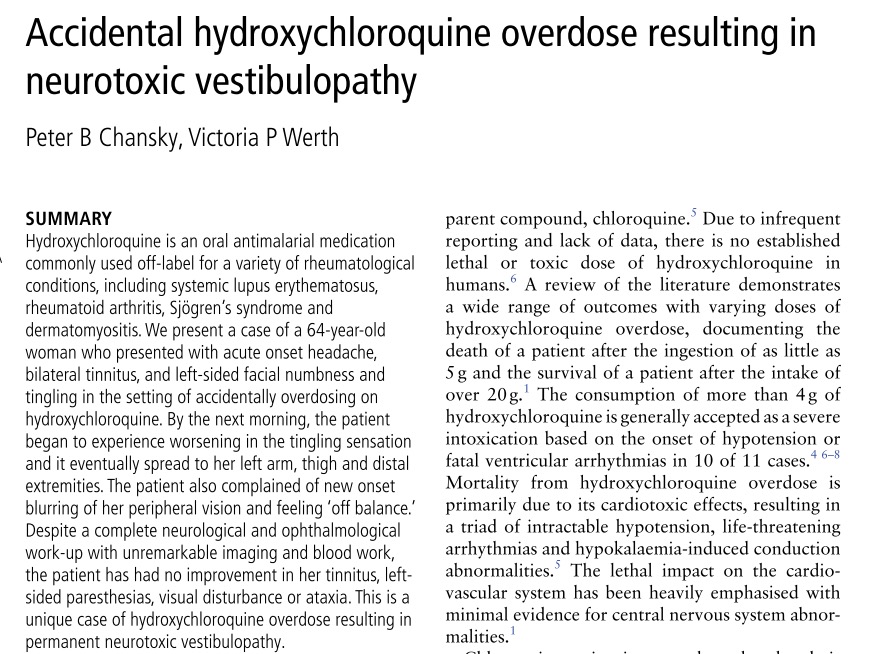

The central (i.e. brainstem), rather than peripheral, nature of these effects is strongly indicated by this subsequent report, which suggests hydroxychloroquine shares the neurtoxic liability of other quinolines. More detail is here: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28404567 ">https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28...

Recall that it was the central nervous system toxicity of quinacrine that prompted to switch to chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine. By the end of WWII, it was clear that quinacrine caused a toxic encephalopathy, which is generally understood to pose a risk of neurotoxicity.

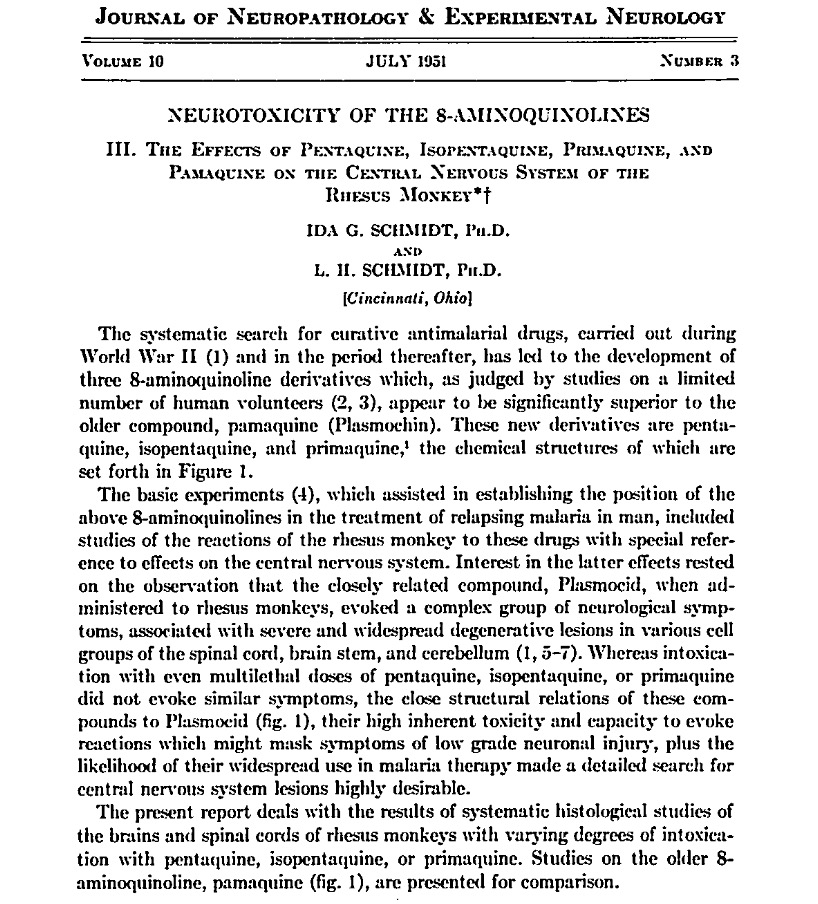

Other closely related quinoline drugs were found to induce a frank neurotoxic injury throughout the brainstem and brain. I discuss this idiosyncratic effect in this paper: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4095041/">https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/artic...

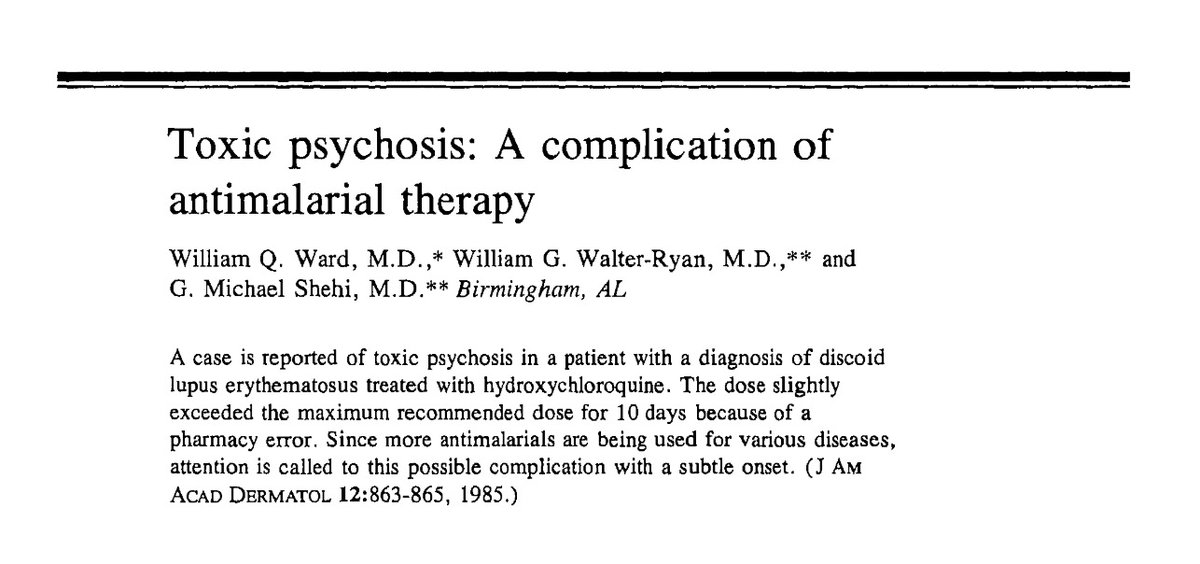

In this context, the subsequent reports of neuropsychiatric adverse effects from hydroxychloroquine can be better understood. Here a case of toxic psychosis resembling that seen with quinacrine is described. Similar cases have typically occurred with low doses, early during use.

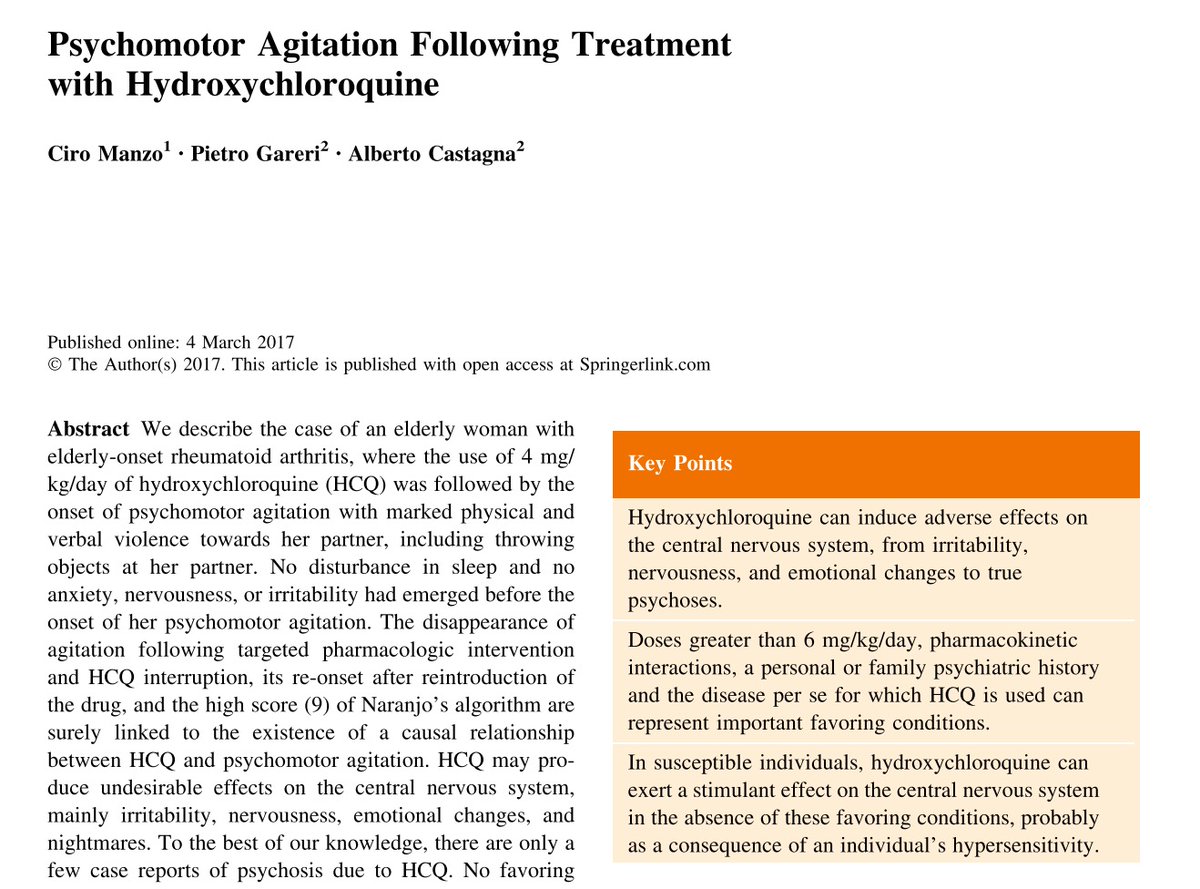

As with other quinolines, such as chloroquine and mefloquine, occasionally more serious psychiatric adverse effects have been reported from hydroxychloroquine without the characteristic preceding prodromal effects, such as insomnia or mild anxiety, first reported from quinacrine.

Absent proper randomized blinded trials to better define the frequency of prodromal neuropsychiatric symptoms from hydroxychloroquine and the reasons for early discontinuation of the drug, today some of our best evidence for the drug& #39;s effects come from pharmacovigilance studies.

So what does this tell us? Hydroxychloroquine is not a safe drug for a minority of the population who appear be susceptible to the drug& #39;s idiosyncratic neuropsychiatric effects. These effects can be more reliably induced at high doses, but may be seen sometimes even at low doses.

At worst, these effects can include toxic psychosis and a likely permanent vestibular neurotoxicity as a result of an induced toxic encephalopathy and neurotoxicity. There is every reason to suspect these effects resemble those seen with other quinolines, including mefloquine.

As with other quinolines, including quinacrine and mefloquine, it appears that at least some more serious adverse effects from hydroxychloroquine can be predicted by the onset of more subtle prodromal psychiatric symptoms, including insomnia, abnormal dreaming, and anxiety.

In the use of these drugs against malaria, the risks posed by these more serious or permanent effects is generally considered to be outweighed in cases of treatment of life-threatening illness. The risk of psychosis is of little relevance if one is dead, the thinking goes.

These effects generally become a consideration in two situations: The first, among those who survive illness and are left with residual disability. The second, among healthy individuals harmed by the drug, after an attempt to prevent illness, or to treat otherwise mild disease.

This is the difficult area of clinical risk-benefit analysis. Today, as hydroxychloroquine and related quinoline drugs are being urgently considered both for prophylaxis and treatment of mild COVID-19 illness, it is tempting to see only the benefits and ignore the risks.

While we cannot say with certainty to what degree, a population prophylaxed against COVID-19 with hydroxychloroquine, chloroquine, or related quinolines will experience more neuropsychiatric symptoms, including insomnia, anxiety, depression, paranoia, and psychosis.

In the midst of the distress caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, it will be tempting to attribute such symptoms to psychological trauma. Mental health professionals should consider the possible lasting effects of quinoline drugs in the evaluation of patients with such symptoms.

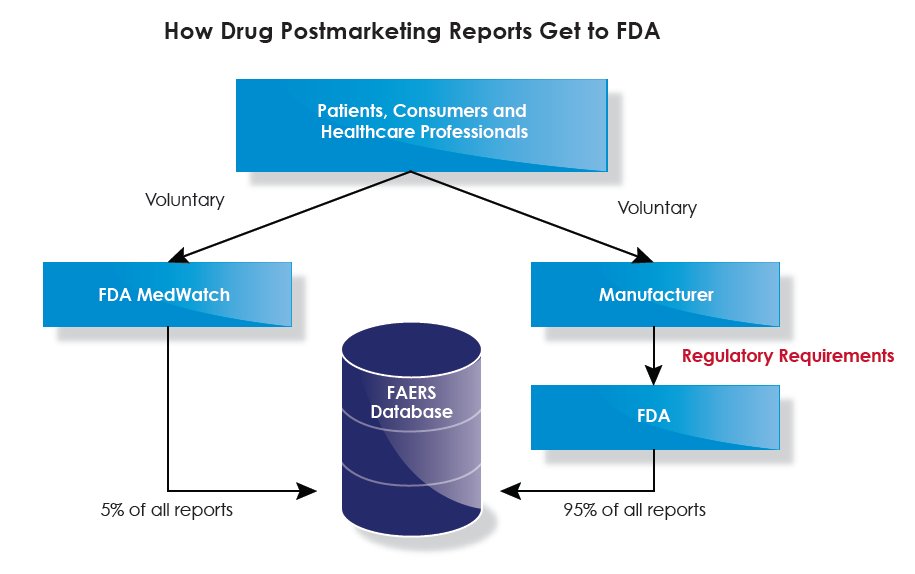

Clinicians, and individual patients prescribed quinoline drugs for COVID-19, should report such symptoms to the FDA MedWatch program. Particularly given the potential scale of use of such drugs, timely and detailed adverse effect reporting is critical to inform evolving policy.

If you found this thread useful, please visit the website of our non-profit, The Quinism Foundation, and sign up for our newsletter to be kept informed of developments in this area. http://quinism.org"> http://quinism.org

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter