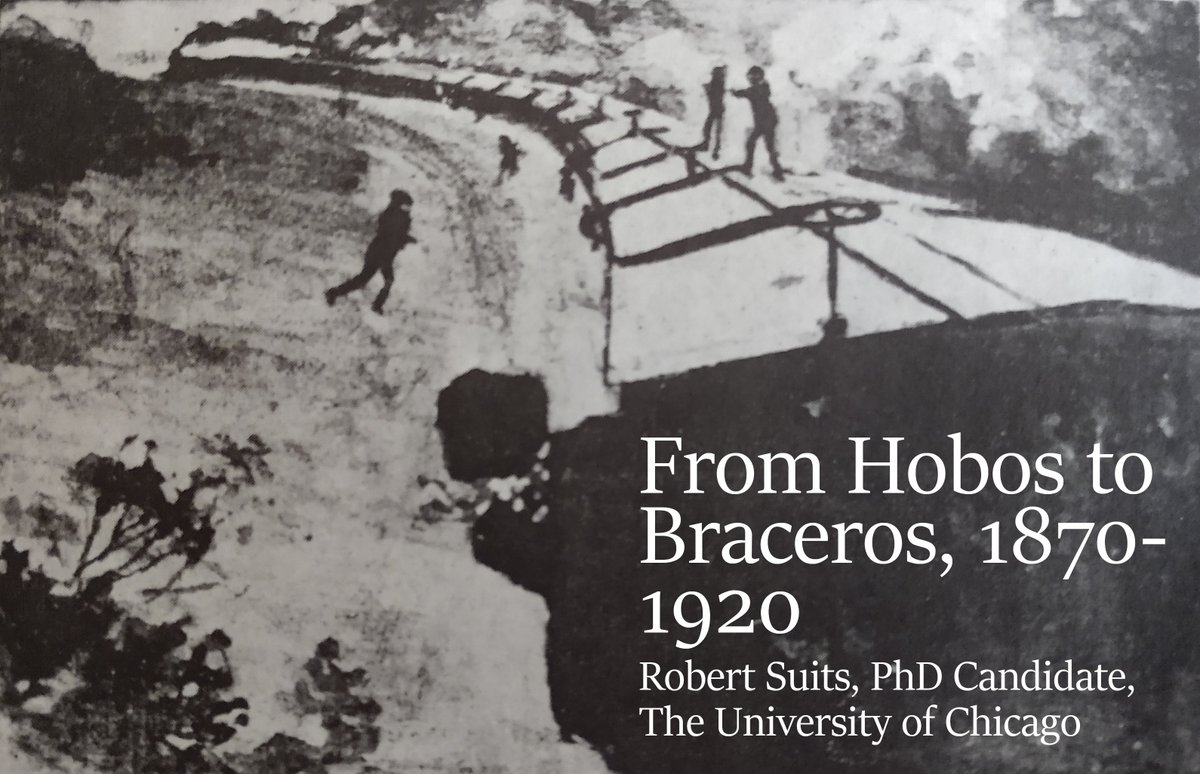

Welcome to another round of #ASEH2020Tweets! Today in my presentation, “From Hobos to Braceros,” I& #39;d like to acquaint you with a small slice of the #envhist of America& #39;s earliest migrant workers, most active from ~1870-the 1920s—hobos.

Hobos are fascinating: transcontinental itinerant workers, central in harvest work and lumberjacking, a counter-culture harboring everything from anarchism to gender nonconformity. They are challenging environmental subjects: they had no home, worked across many environments.

In 1900, most migrant agricultural workers were hobos. Only 50 years later, hobos were nearly gone, and most of that work was done by Mexican-American braceros. How did this happen? One critical element—the subject of my research—lies in their relationships to the environment.

Today, I& #39;d like to focus on just one part of that relationship: transportation. I argue that a subtle shift in railroad technology explains why this labor transition was intimately entangled with energy and the environment. ( #energyhistory)

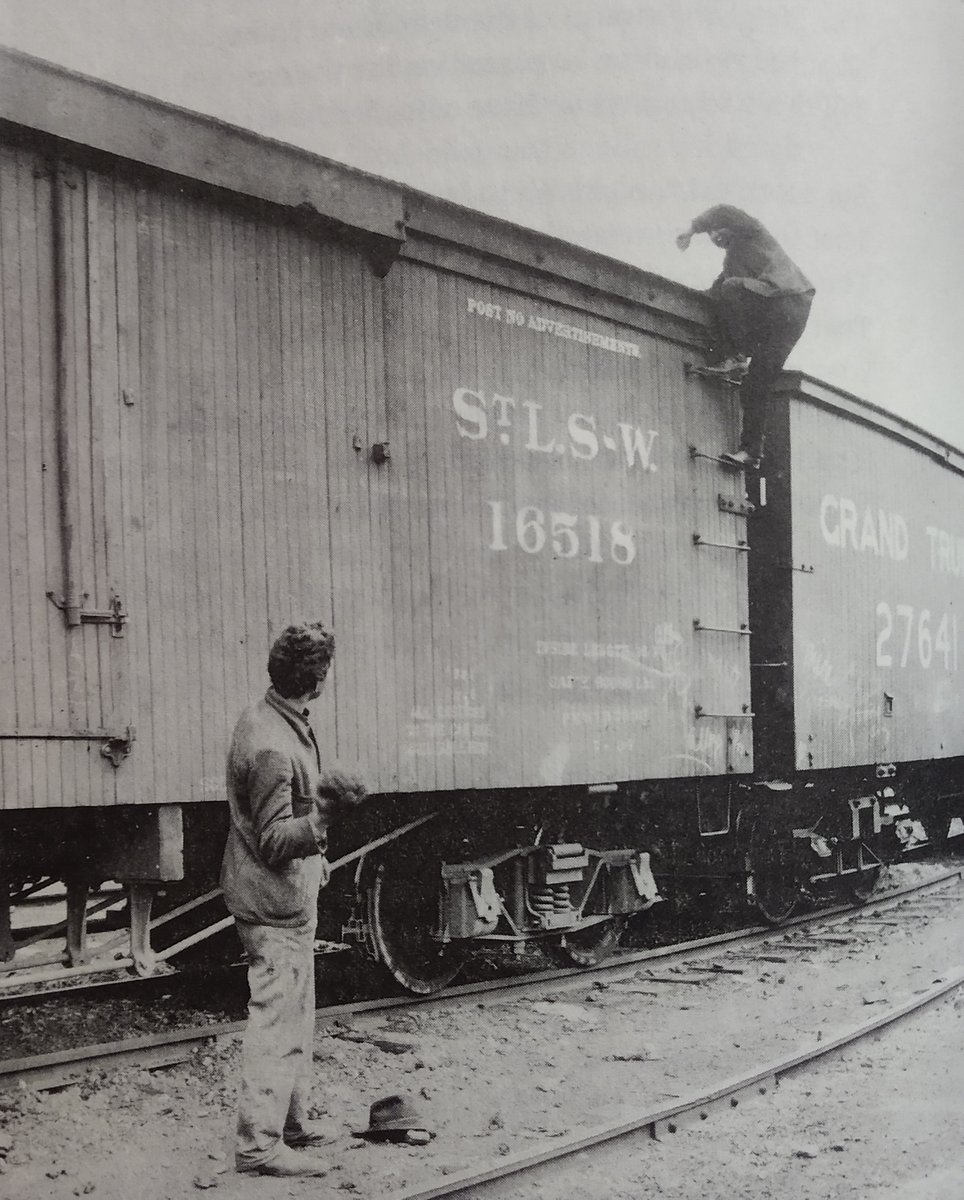

Nearly every hobo who wrote a memoir describes "beating their way" using the railroad. In other words, stealing rides from the railroads. They worked so many odd jobs that paying to get between them would have eaten up all their wages. So they rode, in boxcars with cattle...

...on traincar roofs, hanging from the edges, in refrigerator cars, or even—and this was a favorite desperate measure—perched somewhere in the metal undercarriage of the train, sometimes with faces only inches above the rail ties at 50 miles per hour, rocks spraying their faces.

They risked and often experienced beatings, maimings, and arrest and incarceration in evading fares.

None of that could deter them. There was no other way to get to their work.

The railroad was the center of hobo life.

None of that could deter them. There was no other way to get to their work.

The railroad was the center of hobo life.

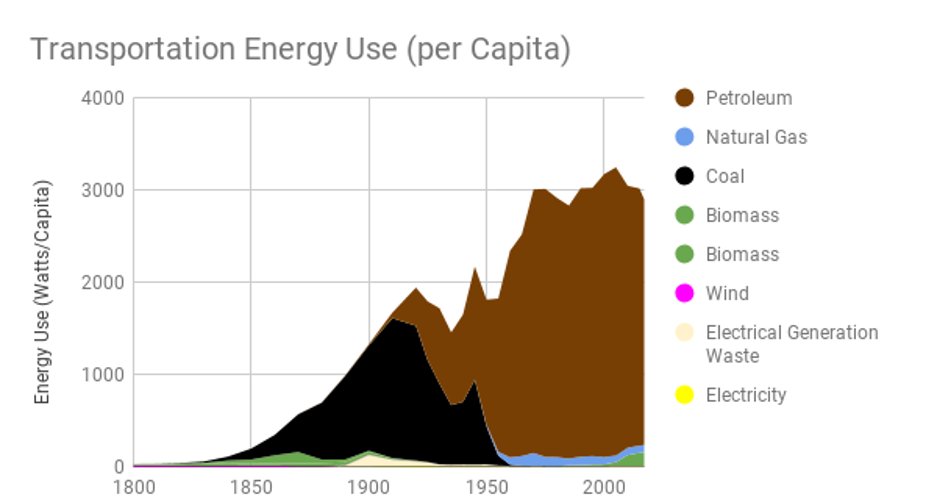

My eureka moment here came from a second project of mine on US energy history. I realized the decline of the hobo was *exactly* concurrent with the energy transition from coal to oil (~the 1920s). The hobo was almost exclusively a product of the coal age. But… why?

You might be thinking it& #39;s about swapping trains for automobiles. Yes, partly! But it goes deeper than that. Railroads themselves transitioned from coal to oil and steam to internal combustion. And that was critical. Steam, specifically, facilitated hobo travel.

The steam railroad, you see, made nearly constant stops -- to let trains pass, but also to take on water and fuel. The water tank is a constant feature of hobo life -- nearly every hobo memoir mentions catching a train at a water tank. It appears in songs, stories, poems.

These constant little stops meant if you were forced off the train by police, you could easily get back on when another train stopped by. If you worked a job in the middle of nowhere, you might not have to walk to the next town. Water tanks gave hobo life flexibility.

Then, in the 1920s, trains started using petroleum. Other, interconnected processes were also at work: agricultural work started using tractors; people started taking cars. Altogether, the hobo -- a product of the steam age, was left behind.

Suddenly, getting to a job site was much more difficult. Stealing rides wasn& #39;t nearly as easy. Hobos might have started to arrange transportation with employers, but that gave employers the final say in who they hired. Enter braceros, whose history is too rich to cover here.

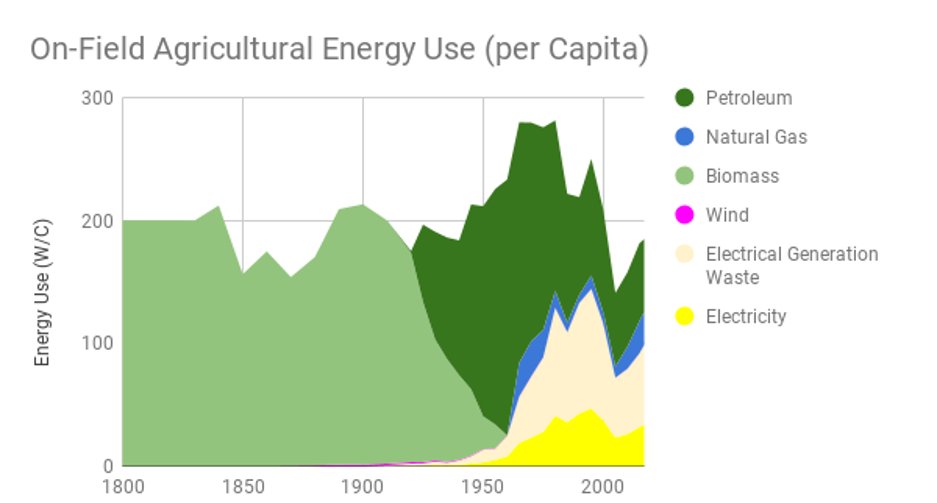

This history matters for so many reasons. On the environmental side, you may have heard about the much-maligned agricultural sector& #39;s role in the climate crisis. But bizarrely, agricultural energy demand has gone virtually unchanged from colonial times to the present day.

But that doesn& #39;t mean our food system isn& #39;t partly culpable for America& #39;s growing energy appetite. It is—but the biggest changes have happened behind the scenes, in how we process food, in how it gets around, and in how its inputs -- nonhuman and human -- get around.

On an even more basic level, of course, it matters because this same transformation has opened us up to profound racism, and embedded inequalities deep into our food system—some of the results of which we’ve seen earlier in this very Twitter conference!

(One final note: I was going to present on this work at ASEH 2020 in Ottawa; I want to highlight the work of my would-have-been-co-panelists here on Twitter. We managed to get our entire panel to sign on to the Twitter conference!)

Our transnational #envhist panel was quite diverse: check out @rebecca_kaplan’s presentation on foot and mouth disease [ https://twitter.com/rebecca_kaplan/status/1240699790163234816],">https://twitter.com/rebecca_k... @sarahthestan’s work on wind energy [ https://twitter.com/sarahthestan/status/1240707753980510208],">https://twitter.com/sarahthes... and @graham_a_pitts’s presentation—coming up next in #ASEH2020Tweets!

Thanks for following along! I hope you enjoyed this little slice of my research, and I& #39;ll be taking any questions now.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter