Byzantium’s Eastern Frontier.

The most sophisticated defensive system of the Middle Ages. It broke the momentum of three centuries of Arab invasions and allowed the Byzantines to resume the offensive, reaching its greatest heights.

A thread.

The most sophisticated defensive system of the Middle Ages. It broke the momentum of three centuries of Arab invasions and allowed the Byzantines to resume the offensive, reaching its greatest heights.

A thread.

Following the second Arab siege of Constantinople in 718, the border between Byzantium and the Caliphate stabilized along the Taurus and Anti-Taurus Mountains.

The Arabs continued to launch large-scale raids and would occasionally seize cities and fortresses.

The Arabs continued to launch large-scale raids and would occasionally seize cities and fortresses.

How did the Byzantines handle this?

There are three basic types of frontier defense: linear, mobile, and defense in depth. Each has its own strengths and weaknesses, and each is best suited to particular circumstances.

The Byzantines used all three.

There are three basic types of frontier defense: linear, mobile, and defense in depth. Each has its own strengths and weaknesses, and each is best suited to particular circumstances.

The Byzantines used all three.

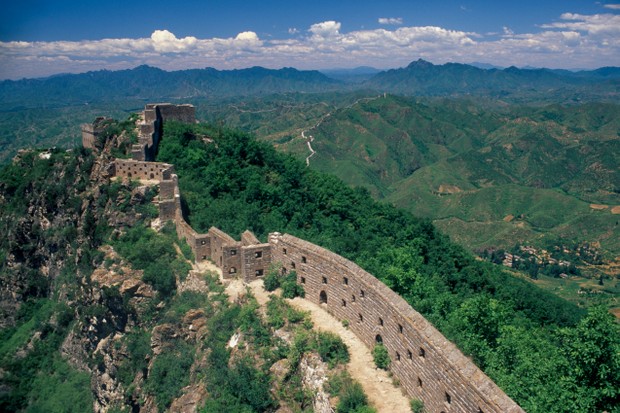

The linear defense is exactly what it sounds like, a long line of forts, walls, and natural barriers—think World War I trenches, the Great Wall of China, the Roman limes.

Often backed by a second echelon of mobile armies than can rush to a point of crisis.

Often backed by a second echelon of mobile armies than can rush to a point of crisis.

Linear defenses are expensive to maintain in strength, which is why they are usually used when one side is much stronger than the other (Romans along the Rhine/Danube) or along narrow, frequently-contested fronts (the Flemish borderlands between France and Habsburg domains).

A mobile defense is far more flexible. When news comes of an invasion, the army simply marches out to fight. Detachments might be prepositioned along likely routes and fortresses may be placed to delay the invaders, but the focus is on the field army.

This was pretty common in Byzantium’s western provinces. Whenever the Bulgarians/Pechenegs/Normans start raiding in Macedonia, the army would march out and fight them. Hopefully they would catch the enemy besieging some fortress, but no matter what, things ended in open battle.

A variant of this is the elastic defense. The defending army falls back under pressure, only stopping to harass and delay the enemy. As the invasion progresses, enemy supply lines get longer while the defender’s get shorter, and is also operating on friendly ground….

Eventually, the advantage shifts so far to the defender that he launches a devastating counterattack, snapping back like an elastic band. Exactly what Russia did against Napoleon or Hitler.

This only works, of course, in countries like Russia with plenty of ground to give.

This only works, of course, in countries like Russia with plenty of ground to give.

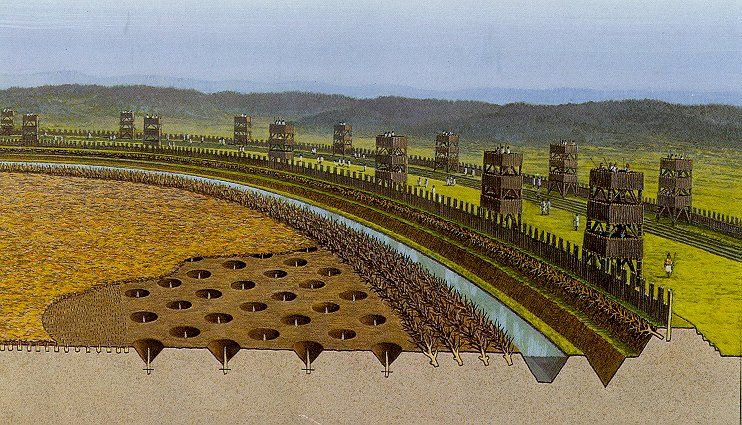

The third scheme, defense in depth, stands between a completely static linear defense and a purely mobile one. It creates a thicket of fortresses and other obstacles that slows down and weakens the attacker.

Like making him slog through mud.

Like making him slog through mud.

The Dutch did this quite literally, flooding their fields to augment the impressive forts that dotted the countryside.

With defense in depth, the invader doesn’t have to attack every strongpoint, but each one he bypasses leaves him vulnerable to harassment by its garrison. He can mitigate this by leaving behind blocking forces, but this just weakens his total force.

This was in fact the strategy of most medieval states. Strong castles dominated their immediate surroundings, creating a logistical nightmare for invaders.

Tough to forage when a castle full of hostile knights sits perched atop a nearby hill.

Tough to forage when a castle full of hostile knights sits perched atop a nearby hill.

Which brings us back to Byzantium’s eastern frontier. The Anatolian plateau was fairly desolate, making logistics difficult.

This created problems for both invaders and defenders, but gave a comparative advantage to the Arabs.

This created problems for both invaders and defenders, but gave a comparative advantage to the Arabs.

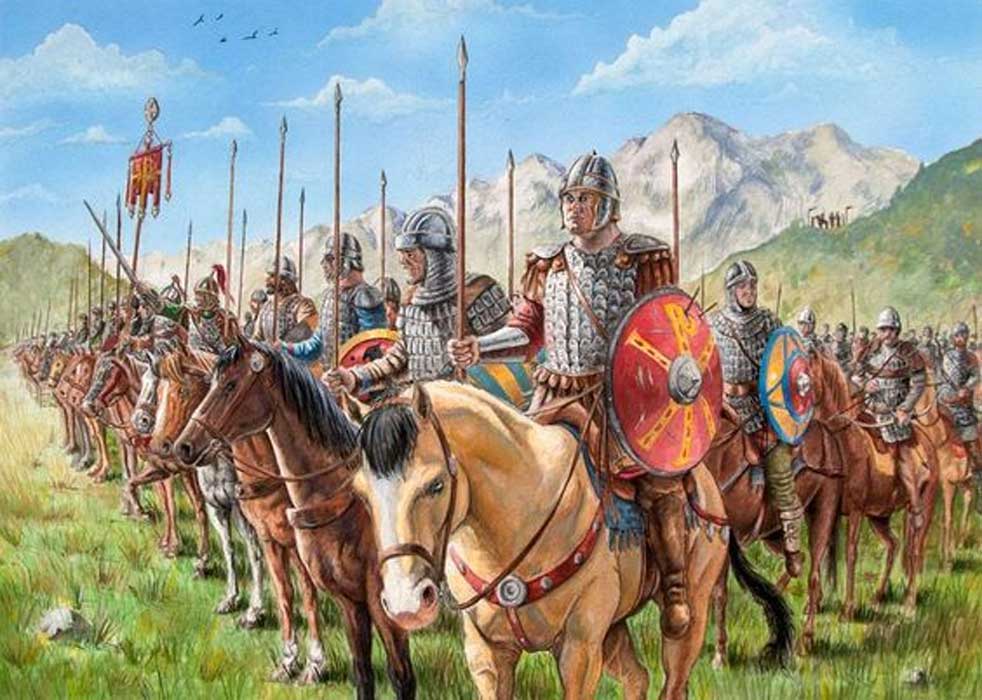

The Arabs launched attacks that, while not large by the standards of conventional warfare, were massive for a raiding party. Following their experience with desert warfare, these all-cavalry forces stayed on the move, plundering the countryside as they went.

This was economically devastating for the empire and tied up a huge amount of manpower that was often needed elsewhere.

It was also dangerous—over time, the Arabs might pry loose enough fortresses to control the passes and resume a full-scale invasion of the empire.

It was also dangerous—over time, the Arabs might pry loose enough fortresses to control the passes and resume a full-scale invasion of the empire.

But because the Byzantines could not maintain large concentrations of troops in a single sector, by the time they mobilized their troops, the Arabs had moved on.

Worse still, they were also often outnumbered in total manpower, especially early on.

Worse still, they were also often outnumbered in total manpower, especially early on.

As the centuries progressed, the Byzantines figured out how to mitigate and eventually how to counter these raids, organically developing an elaborate system that reached its apex in the mid-10th century.

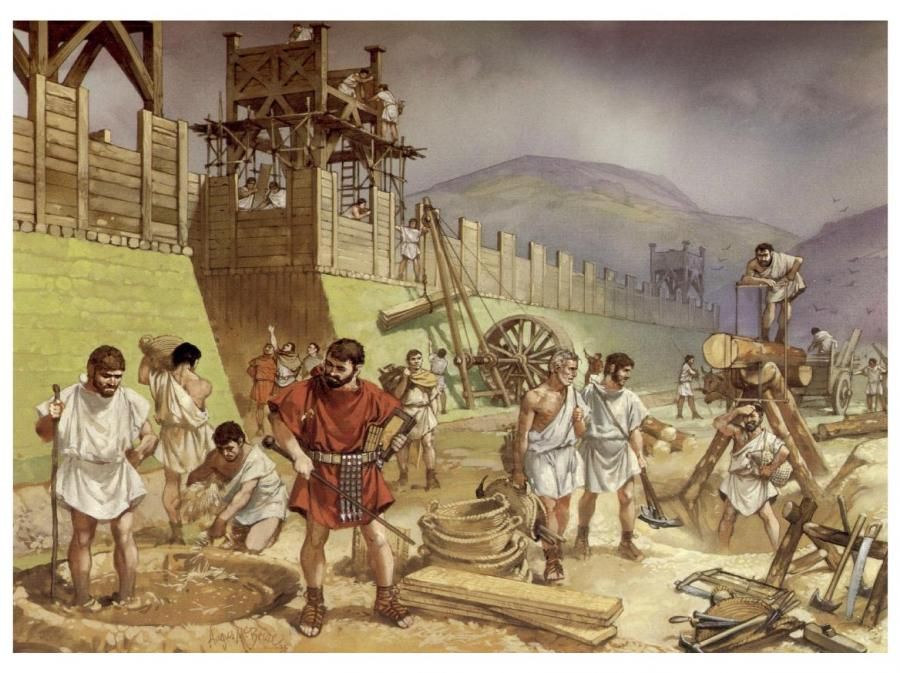

Arab raiding parties gathered in Syria in August or September. Scouts and spies would try to figure out their planned route, allowing the Byzantine frontier commander to send troops to block the passes through the high Taurus and Anti-Taurus Mountains.

A natural linear defense.

A natural linear defense.

Sometimes this alone stopped the raiding party dead in its tracks or even scared it off. More often, the mobile raiders just found another route.

But it still gave the Byzantines intelligence and critical time, allowing them to assemble forces near the new route.

But it still gave the Byzantines intelligence and critical time, allowing them to assemble forces near the new route.

This was complemented by a system of warning beacons that stretched back to Constantinople itself, putting all of Byzantine Asia on alert. Everyone from the emperor down to local commanders could begin making preparations.

This did not mean that the Byzantines would assemble a massive field army to fight a single decisive battle, however.

Fortress garrisons prepared their walls, thematic commanders gathered mobile forces, villagers brought flocks and crops to safety.

Fortress garrisons prepared their walls, thematic commanders gathered mobile forces, villagers brought flocks and crops to safety.

At first, the field forces would strictly shadow and observe the enemy. Like the Arabs, they were mostly cavalry and could move quickly.

The Byzantines would only fight when they had clear superiority, launching night attacks or ambushing isolated raiding detachments.

The Byzantines would only fight when they had clear superiority, launching night attacks or ambushing isolated raiding detachments.

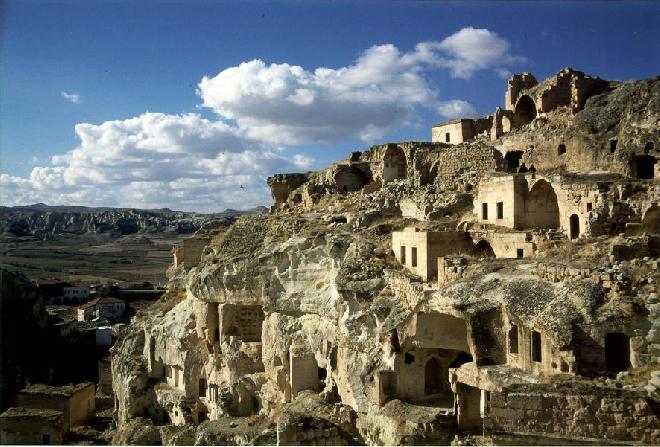

Meanwhile, centuries of raids had forced Anatolian villagers to harden their settlements. They built walls, relocated to higher ground, and developed alert systems to bring crops and livestock to safety when raiders were near.

This made it harder for the Arabs to loot and forage, often forcing them to attack strongpoints. Even when they were successful, it narrowed their advance, slowed them down, and gave the Byzantine field forces opportunities to wear them down.

An organic defense in depth.

An organic defense in depth.

Sometimes this was enough to turn back the raiders. Armies can only go so far without provisions and men hoping for easy loot could become quickly demoralized.

Most of the time, the Arabs had more luck. After several weeks or months, they would head back home laden with loot.

Most of the time, the Arabs had more luck. After several weeks or months, they would head back home laden with loot.

Their spoils slowed them down, of course, and they were already worn down by attrition and the fatigue of campaigning.

The Byzantines, meanwhile, had had time to gather a large field army. They were ready for a decisive battle.

A classic elastic defense.

The Byzantines, meanwhile, had had time to gather a large field army. They were ready for a decisive battle.

A classic elastic defense.

But it was even more complex than that. The Byzantines also placed infantry in the passes along the Arab line of retreat, trapping them between the mobile forces and a linear barrier. Hammer on anvil. The Arabs were forced to give battle on exceptionally unfavorable terms.

These tactics, described in the manual “On Skirmishing”, were brought to perfection by the future emperor Nicephorus Phocas and his brother Leo.

Together, they broke the power of the emir of Aleppo, Sayf ad-Dawla, the last Arab ruler to seriously threaten the frontiers.

Together, they broke the power of the emir of Aleppo, Sayf ad-Dawla, the last Arab ruler to seriously threaten the frontiers.

After this, the Byzantines took the offensive into Syria. Under Nicephorus II, John Tzimisces, and Basil II, they recovered Antioch, subjected Aleppo to tributary status, and pushed down the Levantine coast.

With Basil’s victories in Bulgaria, the apogee of Byzantium.

With Basil’s victories in Bulgaria, the apogee of Byzantium.

The final victory in Anatolia was won by a few 10th-century generals, using a very specific and deliberate method. But the techniques they drew from were the work of centuries, developed through bitter experience over the long course of the Arab-Byzantine wars.

For perspective on the problems the empire faced after the eastern frontier system broke down, check out "Midway Through the Plunge".

https://www.amazon.com/dp/B07P68KCBG/ ">https://www.amazon.com/dp/B07P68...

https://www.amazon.com/dp/B07P68KCBG/ ">https://www.amazon.com/dp/B07P68...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter