Thread (1/16). How is that our economic statistics suggest workers have been making slow but steady progress in recent decades, while popular perception is that their family finances are coming under increasingly untenable pressure? I& #39;ve been working on this, here& #39;s my answer:

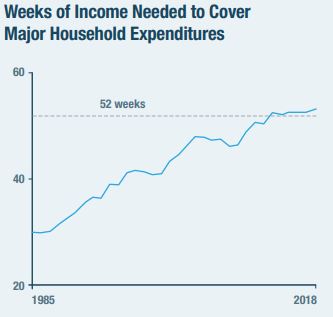

2/ Punchline: Popular perception is correct. In 1985, the typical male worker could cover a family of four& #39;s major expenditures (housing, health care, transportation, education) on 30 weeks of salary. By 2018 it took 53 weeks. Which is a problem, there being 52 weeks in a year.

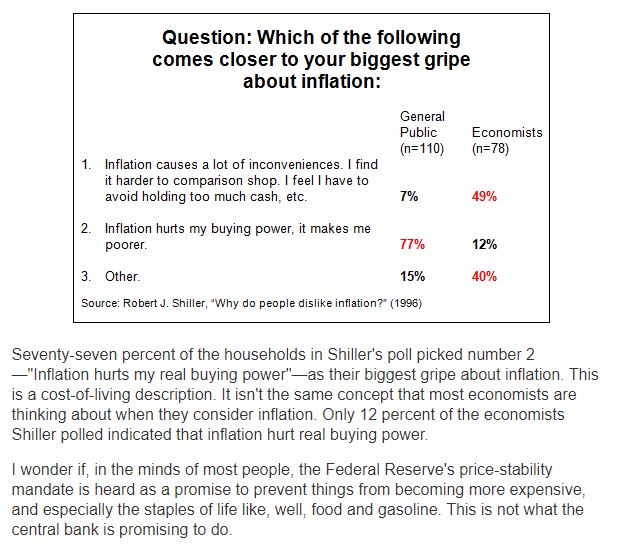

3/ Why do our inflation-adjusted data say otherwise? Because inflation does not assess affordability. You don& #39;t have to take my word for it. Here& #39;s a neat study by Nobel laureate Robert Shiller making the point, as cited by Fed economist Michael Bryan: http://econintersect.com/b2evolution/blog1.php/2014/07/10/alternative-measures-of-inflation-part-3-the-challenge-of-communicating-price-stability">https://econintersect.com/b2evoluti...

4/ For example, our inflation-adjusted data say car prices have not increased since the mid-1990s. Obviously, that& #39;s not remotely true. What economists are saying is that cars have gotten better so the higher sticker price doesn& #39;t reflect inflation, it reflects higher quality.

5/ Fair enough. But, if you& #39;re a family that needs to buy a minivan, while it& #39;s nice that the 2018 Grand Caravan ($26,300 in 2018) has many features the 1996 Grand Caravan ($17,900 in 1996) did not, you still face the problem that you need an extra $8,500 to buy one.

6/ A key assumption of our inflation-adjusted analyses is that old products are still available. Don& #39;t like / can& #39;t afford the $26K 2018 Grand Caravan, go buy the $18K 1996 one instead. Except you can& #39;t. Same problem is even more pernicious in areas like housing and health care.

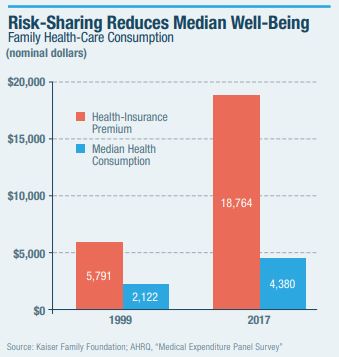

7/ Another huge problem with health care, especially, is that everyone has to pay for shared risk. If a million-dollar miracle cure needed by 1 in 1,000 households drives up everyone& #39;s insurance premium, that& #39;s not inflationary. You now have access to the million-dollar cure.

8/ Again, fair enough. But we have to recognize that the median family must now pay more for health insurance and will not use the cure. Last 20 yrs, the typical family& #39;s health care consumption has gone up $2K, but their premium has gone up $13K. No wonder they feel worse off.

9/ So, start putting these things together, and you find a situation where major costs facing families have skyrocketed unsustainably in ways our economics is incapable of acknowledging. Then we gloss over the underlying assumptions and say "inflation-adjusted wages look good."

10/ When we say "inflation-adjusted wages look good," we are actually saying "if you could take your wage back to 1970 and spend it, you& #39;d be better off than you were at the time with a 1970 wage." I mean, maybe that& #39;s interesting. But it doesn& #39;t describe lived experience.

11/ There are lots of good reasons to have our existing technical measures. Macroeconomists need them. But alongside them, we need a perspective that looks at the costs households actually face as compared to the wages that workers actually earn.

12/ I& #39;ve created a measure I call the Cost-of-Thriving Index (COTI), comparing nominal costs to a family for housing, health care, transportation, and education with nominal weekly wage of median male worker. My new @ManhattanInst report details rationale, assumptions, sources.

13/ COTI shows that while the nominal median male wage rose from $443 to $1,026 from 1985 to 2018 (132%), the expected cost of his family& #39;s major expenditures rose from $13,227 to $54,414 (311%). He used to need 30 weeks of work to cover those costs, now he needs 53.

14/ Some might say: that& #39;s absurd, of course a family can& #39;t cover an entire health insurance premium, a 3-bed house, and college for two kids on a single worker& #39;s salary, that& #39;s not how anyone lives. But COTI shows that in the past a family COULD do that. Just not anymore.

15/ Conservatives especially should be wary of taking comfort that massive government supports make up the gap. If you& #39;re thinking, "well, but of course we subsidize health care and college heavily," that& #39;s not a defense of the status quo. It& #39;s a blaring red siren.

16/ The point isn& #39;t to validate some specific policy agenda, but to introduce a new set of facts that should help inform the starting point for our debates. How to get higher wages? How to get lower costs? Let& #39;s at least acknowledge these are pressing and long-worsening problems.

[Insert compulsory SoundCloud joke. -ed]

You can read the full report with technical analysis @ManhattanInst.

https://www.manhattan-institute.org/reevaluating-prosperity-of-american-family

And">https://www.manhattan-institute.org/reevaluat... my narrative essay presenting the full argument has just been published by @AmericanAffrs. That is all. https://americanaffairsjournal.org/2020/02/the-cost-of-thriving/">https://americanaffairsjournal.org/2020/02/t...

You can read the full report with technical analysis @ManhattanInst.

https://www.manhattan-institute.org/reevaluating-prosperity-of-american-family

And">https://www.manhattan-institute.org/reevaluat... my narrative essay presenting the full argument has just been published by @AmericanAffrs. That is all. https://americanaffairsjournal.org/2020/02/the-cost-of-thriving/">https://americanaffairsjournal.org/2020/02/t...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter