First listening to the Beatles at age 35 thread

“You can& #39;t have Bach, Mozart and Beethoven as your favorite composers," Michael Tilson Thomas once said. "They simply define what music is." On another plane, the same is true of the Beatle, whose super-canonical status means I& #39;ve never felt the need to actively like them.

Saying you "like" or "don& #39;t like" the Beatles has only as much force as saying you "like" or "don& #39;t like& #39; the Bible: the sheer depth and breadth of cultural influence involved obviates all personal judgment. Even avowedly non-believing modern Westerners have a Biblical worldview.

Similarly, we& #39;re all Beatles listeners — even if, like me, we& #39;ve never owned a Beatles album or even listened to one all the way through. But despite having never pursued their music, I& #39;ve long meant to gain an understanding of the Beatles as cultural nexus, as body of knowledge.

And so I& #39;m spending the next three months listening seriously to each and every one of the Beatles& #39; studio albums, in order, one album per week. Accompanying reading will include Ian MacDonald& #39; "Revolution in the Head," Rob Sheffield& #39;s "Dreaming the Beatles," and other volumes.

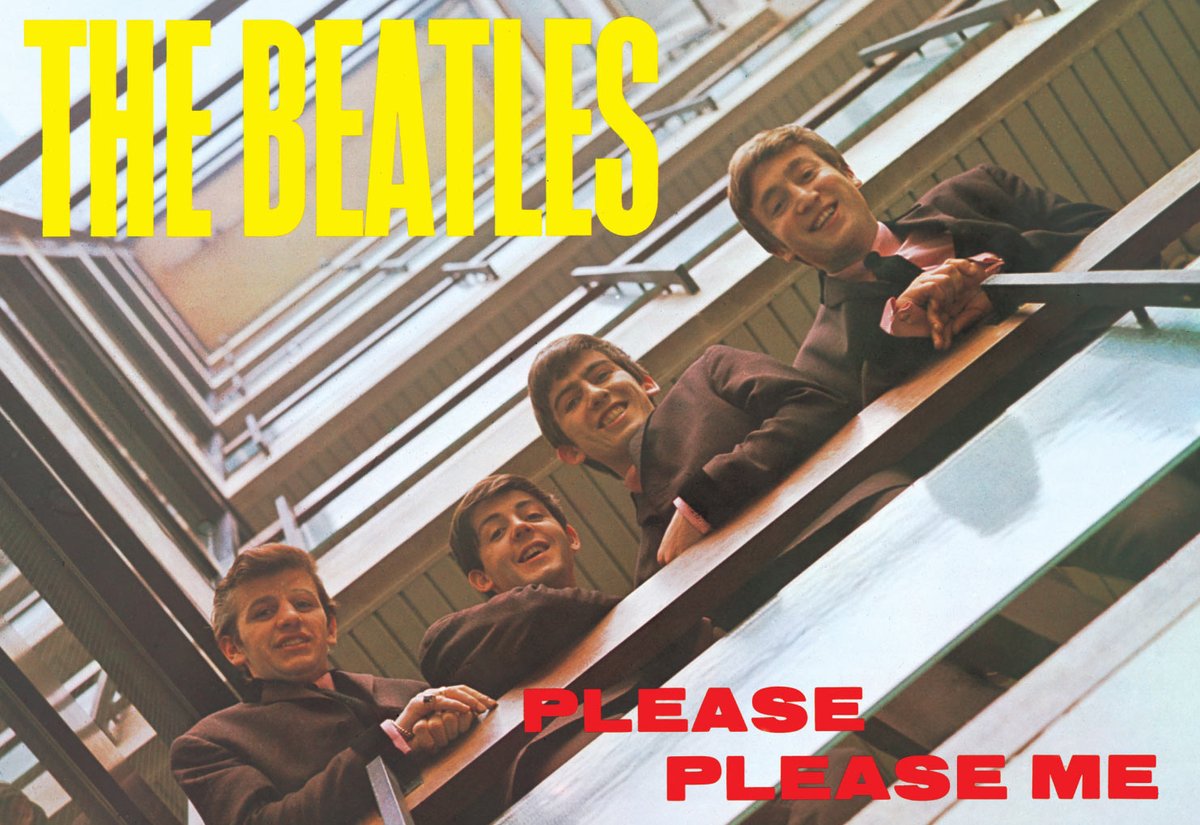

Please Please Me: Their debut album, famously recorded in one day-long session. Or rather most of it was, everything but the four singles that came out before. Those include "Love Me Do," one of the songs I already knew by heart despite never once having voluntary listened to it.

"Twist and Shout" I& #39;d similarly internalized in detail through cultural osmosis. But many songs I& #39;d never heard before, and the album& #39;s mixture of the thoroughly familiar and the totally unfamiliar is, in microcosm, what I expect from this Beatles listening project as a whole.

Perhaps the songs in between, those I& #39;d encountered only now and again in life, hold the most interest. The opener, "I Saw Her Standing There," is one such song. The opening lines ("She was just seventeen / You know what I mean") would make you low-hanging MeToo fruit these days.

But then, the Beatles themselves were only in their early twenties at the time. This is, as I understand it, their "boy-band" phase, though they& #39;d somehow already managed to put in a Gladwellian amount of gigging hours in order to develop the live set Please Please Me records.

Beatles die-hards prefer the early stuff, but I& #39;m looking forward to the thematic variety to come. Here it& #39;s almost all about love, which is to say sex — but then, per Larkin, sexual intercourse began in 1963, "between the end of the Chatterley ban u2028and the Beatles’ first LP."

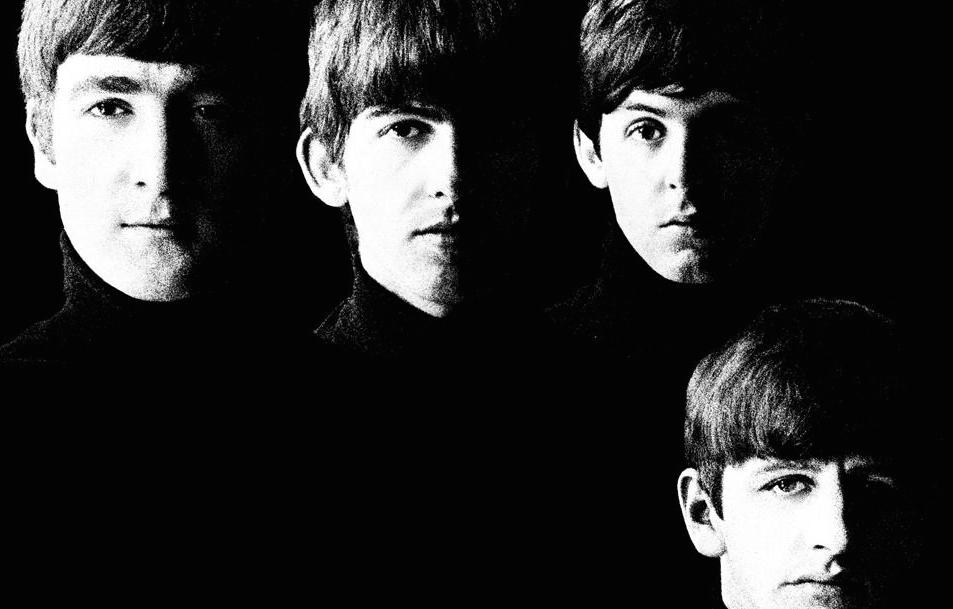

With the Beatles: It surprises me that I remember hearing nearly nothing on this 56-year-old album before. When I first put it on, I thus heard what was to me more or less a "new" Beatles album, a listening experience for which any serious Beatles enthusiast would no doubt kill.

Even before I started listening to the Beatles I understood that each member& #39;s having a distinct identity (sometimes opposed to the others& #39;) makes the band more naturally interesting — and even more so the fact that aspects those identities come through in the songs themselves.

(Bill Clinton once claimed that the Beatles embodied everything in the sixties. That is, P.J. O’Rourke later wrote, "everything in the sixties was either brilliant but troubled, earnest but flaky, stupid, or Paul McCartney.")

Though many Beatles fans identify themselves by declaring a "favorite Beatle" (as Harry Potter readers might claim to belong to a Hogwarts dormitory), their discussions of the band also implicitly acknowledge an effectively fixed and agreed-upon respect hierarchy of its members.

The position in that hierarchy of each of the lower three Beatles seems to owe to his particular tendency toward excess. "Till There Was You" would sound like the debut of Paul& #39;s famed weakness for the saccharine, but the song is of course a Broadway showtune, not one of his own.

While not inclined to worship a figure like John (at least not his messianic late-60s incarnation), I have to admit that his opener "It Won& #39;t Be Long" holds up more solidly than any Beatles song I& #39;ve yet heard. On first play, I felt like I was hearing something new and thrilling.

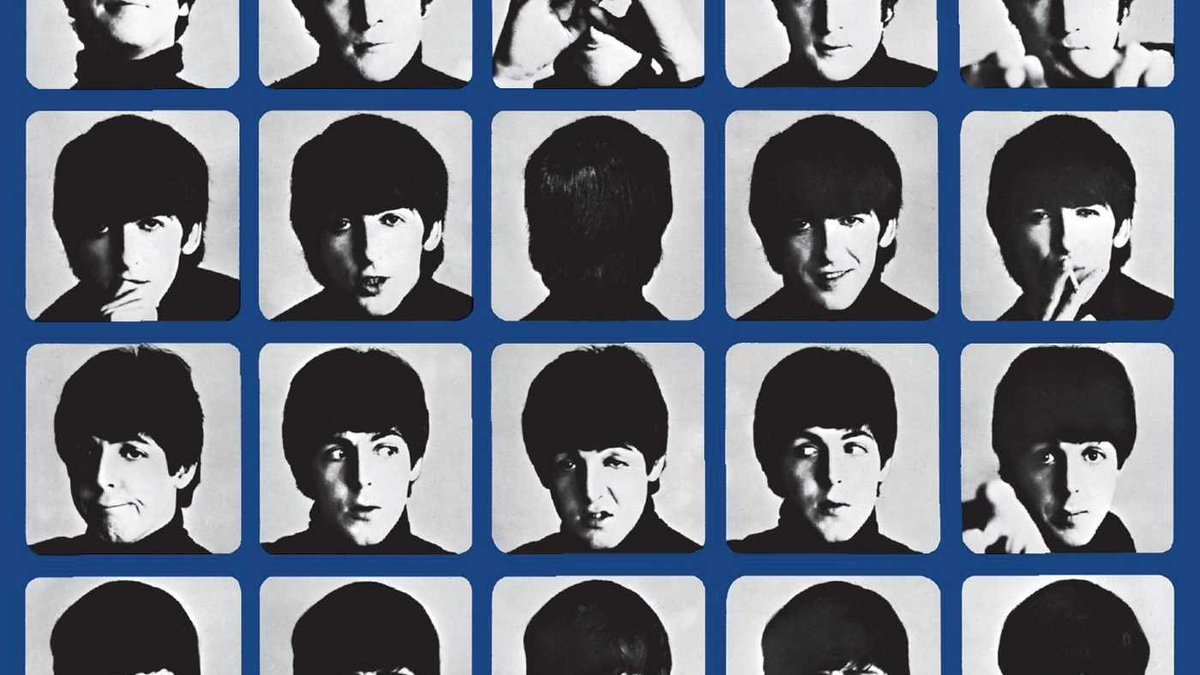

A Hard Day& #39;s Night: Much more familiar territory for the non-Beatles-listener than its predecessor. Even before putting this album on, I must have heard the title song and "Can& #39;t Buy Me Love" hundreds of times, all inadvertently. (Maybe more; both run less than three minutes.)

More notably, this one has songs I& #39;d often heard and could recognize as the work of the Beatles without ever having known their names: "I Should Have Known Better," "If I Fell," "And I Love Her" — admittedly, I could have guessed that last one — all highly "Beatlesque" melodies.

I have yet to crack my Beatles books, but I find myself wishing someone would write one only about the band& #39;s throwaway songs: "I& #39;m Happy Just to Dance with You" on this album, "Little Child" on the last. I also find myself wishing they& #39;d sing about something other than girls.

The first side of A Hard Day& #39;s Night is the soundtrack for the eponymous Beatles movie, which I saw about 20 years ago. But somehow I can& #39;t call to mind any other context in which I must so often have heard the songs that were already familiar to me. They were all just... around.

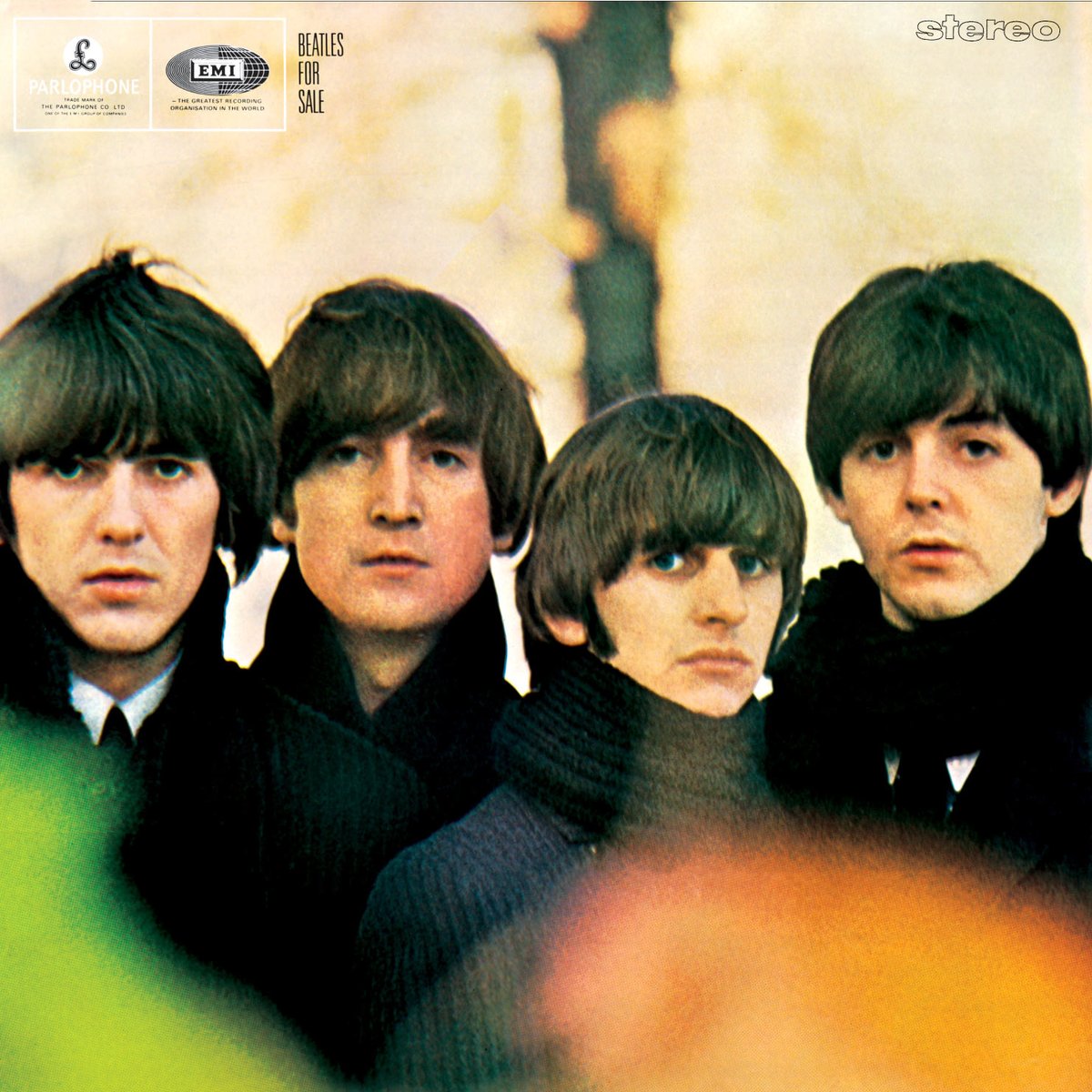

Beatles for Sale: I& #39;ve enjoyed every Beatles album I& #39;ve listened to so far over this past month. Still, I can& #39;t help but notice that none of their individual tracks have turned into "earworms" — i.e., songs that I don& #39;t just want to but need to hear again, and again, and again.

Admittedly, most of my own earworms in recent years have tended to come out of old school, Japanese city pop, west-coast yacht rock, "future funk," etc. — pop-musical realms about as far removed from as you can get from early Beatles records. https://youtu.be/oNQkWgrNbzU ">https://youtu.be/oNQkWgrNb...

The overexposure of certain Beatles hits, on which I& #39;ve touched before, must also have something to do with it. There& #39;s nothing wrong with "Eight Days a Week," say, but I& #39;m not sure what one more spin of it would get me at the margin.

But Beatlemania, at its height when Beatles for Sale came out, was surely driven by nothing if not the need of 1960s teenagers to hear certain Beatles songs over and over again. I& #39;ve thought of the Beatles as an "album band," but in 1964 they were still about the two-minute song.

They were also more about early rock-and-rollers than I& #39;d quite realized, an affinity underscored by Beatles for Sale& #39;s abundance covers of Carl Perkins, Buddy Holly, Chuck Berry — cultural entities I know most intimately as Jim Jarmusch references. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dLFVprIjtpw">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

LITERARY INTERLUDE: A highly relevant Murakami story, newly published by the New Yorker: "This might seem strange, but it wasn’t until I was in my mid-thirties that I sat down and listened to & #39;With the Beatles& #39; from beginning to end." https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/02/17/with-the-beatles">https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/...

Help: Of all the albums so far, this one must surely sound most familiar to the non-Beatles-listener. There& #39;s the title track, "You& #39;ve Got to Hide Your Love Away," "Ticket to Ride" — though somehow I can& #39;t force the Carpenters version out of my head — "Yesterday"...

I told a more Beatles-savvy English friend about this project a while back and he immediately laid into "Yesterday," calling it "saccharine" and one of the very worst Beatles songs. But like much of the band& #39;s best-known work, I& #39;ve already heard it too many times to evaluate it.

It did occur to me, though, that there must be a quiet consensus among hard-core fans as to which popular Beatles songs are actually bad, or at least undeserving of their place in the Beatles canon. (My friend also told of hating "Hey Jude," though he respects its musicianship.)

There must also be a consensus about when the Beatles turned from "single band" to "album band," as I described myself thinking of them earlier. Though technically a soundtrack, Help doesn& #39;t quite possess the coherence I expect from an album. But I suspect that& #39;s about to change.

I will say this for "Yesterday": its arrangement for guitar and recording by just Paul and a string quartet set a precedent for the sound of Nick Drake, the first English singer-songwriter of the 1960s in whom I took a great interest. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=idcaRTg4-fM">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

CINEMATIC INTERLUDE: I& #39;d actually seen A Hard Day& #39;s Night, the movie, once before. It was one of two 1964-themed archival screenings at the 1999 Florida Film Festival, the other being Dr. Strangelove. (The headline picture of the festival as a whole: The Blair Witch Project.)

The depth of my Beatles ignorance was even greater at age 14 than it is at age 35. I recognized only a few of the songs in the movie, and most of those vaguely. I don& #39;t think I could even reliably tell the Beatles themselves apart — although to be fair, they all dressed the same.

Yet I enjoyed A Hard Day& #39;s Night as I had enjoyed few other "old movies" (apart from Dr. Strangelove) to that point. Even if I didn& #39;t respond immediately to the music, I could feel in the film the sheer vitality of the Beatles, both as a band and a greater cultural phenomenon.

This vitality has kept the first Beatles movie cinematically current through the generations — and, I suspect, has kept the Beatles& #39; records musically current through the generations as well. There& #39;s plenty of music I enjoy made today, but would I really call any of it "vital"?

Vitality benefits from constraints — constraints the success of the Hard Day& #39;s Night movie lifted from its follow-up Help!, which replaces real pressures of Beatlemania with a couple of mad scientists and an Indian death cult like in the second Indiana Jones.

But the film does have unintentional documentary value, capturing the band as it does just after they& #39;d discovered cannabis. Famously shot in a "haze of marijuana," it marks the fulcrum point between the early-60s Beatles and late-60s Beatles. (Neat that it came out in mid-1965.)

Rubber Soul: This feels like what I& #39;ve been waiting for, the first Beatles album conceived as an album, not a collection of songs, and the first on which they used the recording studio as an instrument in itself — and thus perhaps the first true "album" as we know the form today.

Not coincidentally, this is also the first Beatles album I& #39;ve felt compelled to listen to through headphones — not earbuds, but over-the-ear headphones. (I also heighten the experience by simultaneously reading Ian McDonald& #39;s track-by-track analyses in "Revolution in the Head.")

"Drive My Car," Rubber Soul& #39;s first track, is one of those common if not unavoidable Beatles songs. It always sounded juvenile in chance encounters over the years, but upon closer listening it seriously impresses me. As an album opener, I& #39;d put it even above "It Won& #39;t Be Long."

"It Won& #39;t Be Long" is on With the Beatles, their second album and the namesake of the new Haruki Murakami story I posted earlier in this thread. Rubber Soul has a similar connection to Murakami& #39;s work: his most popular novel takes its name from its second track, "Norwegian Wood."

I read Norwegian Wood before I knew the Beatles or Japanese. Not only was it lost on me that the book& #39;s original title (ノルウェイの森, "A Forest in Norway") misinterpreted the song, I had no idea what the song itself sounded like. It was a cultural reference without a referent.

But much like With the Beatles in "With the Beatles," Murakami uses "Norwegian Wood" in Norwegian Wood primarily as a memory trigger for the narrator: he happens to hear the song on an airplane in the late 1980s, bringing back memories of his student days in the late 1960s.

Murakami doesn& #39;t seem to believe in "the Sixties" as a political moment; nor, really, does MacDonald, who astutely contextualizes the Beatles in that period and sizes up the period itself. But MacDonald also points up the Sixties-skepticism from an unlikely source: John Lennon.

John seems to have been more skeptical at some times than others. "I was a hitter," he once said. "I couldn& #39;t express myself and I hit. I fought men and I hit women. That is why I am always on about peace." That hitter comes through on Rubber Soul& #39;s closer, "Run for Your Life."

Could a pop star today sing the line "I& #39;d rather see you dead, little girl, than to be with another man" (borrowed from Elvis though those words were in the first place)? Alongside "You Can& #39;t Do That" on A Hard Day& #39;s Night, the song reveals a major aspect of John& #39;s magnetism.

Though called "sexist" by MacDonald and later disavowed as misogynistic by John himself, it nonetheless exudes a certain strength — in the old sense, the strength of possessing and using force, the strength of the law-giver — that one can hardly imagine hearing from, say, Paul.

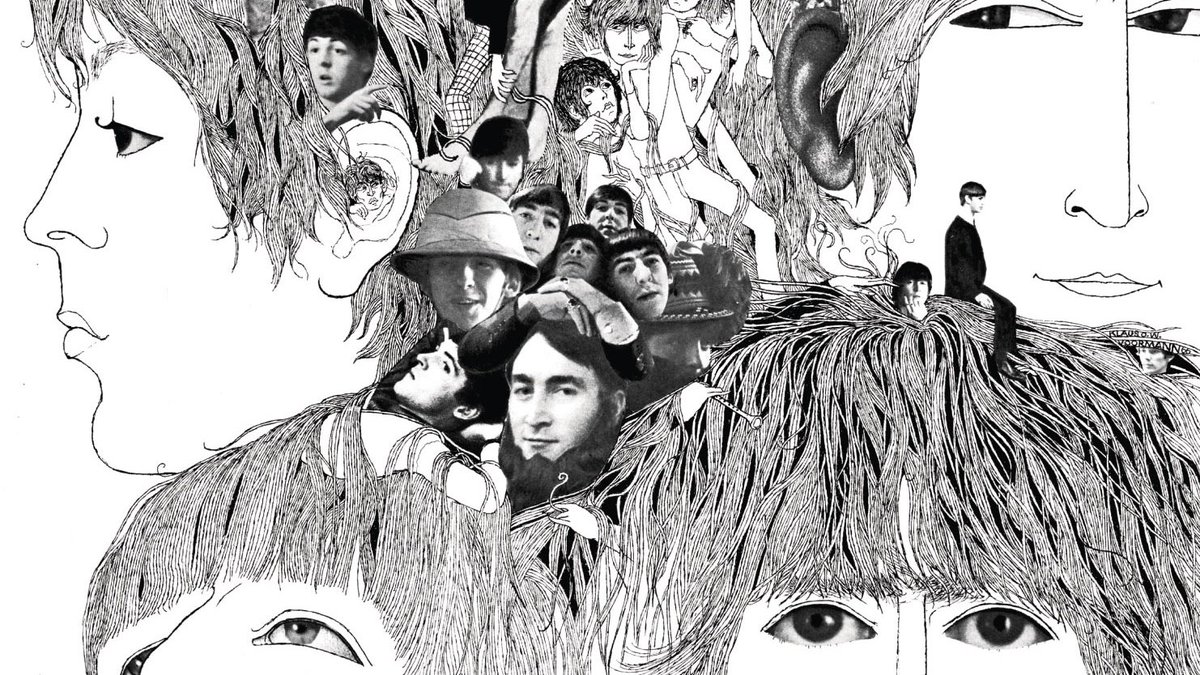

Revolver: The best Beatles album, at least according to current critical consensus. Sgt. Pepper, which I& #39;ll listen to next week, used to hold that title, but it seems to have committed the sin (to the ears of the past couple decades& #39; rock writers) of being a concept album.

No track on Revolver is compromised by a theme; or rather, each is individually uncompromising. I first heard "Taxman" about 15 years ago, and even then a Beatles song complaining about income taxes surprised me. (Critics now balk at the "privilege" of it all, though I enjoy it.)

I& #39;d like to think that, had I been around at the time, the Beatles& #39; studio experimentalism would have been what drew me to their music: using only a string octet behind Paul, electronically creating an old-man voice for John, George going Hindustani classical on the first side...

To say nothing of John& #39;s closer "Tomorrow Never Knows," which with its tape loops, backward guitars, and lyrics borrowed from the Tibetan Book of the Dead, must have sounded like a transmission from another reality. But who under the age of 65 can know how it felt to receive it?

The deeper I get into the Beatles catalog, the more I realize I can& #39;t fully experience it unless I somehow erase my knowledge of all music that came after. Nobody cares how far a band pushes boundaries in the studio today, but when the Beatles did it even the Queen took note.

Revolver came out in August 1966, three months after the Beach Boys& #39; Pet Sounds. Some describe the years leading up to Revolver as a competition between the Beach Boys (or rather Brian Wilson) and the Beatles to make the most ambitious album, a frame I find hugely fascinating.

Revolver won that competition, at least according to the currently accepted narrative. But a world where pop-music studio geniuses engage in esoteric battle while millions wait in perpetual desperation for the next record is, in some sense, the world I want to live in.

If I like Revolver best so far, it& #39;s because I never got into rock. Which is to say, I never accepted rock& #39;s veneration of raw, off-the-cuff self-expression through electric guitar, drums, bass, and little else. Painstaking studio craft — even just the idea of it — gets me going.

Hence the unsurprising fact that my favorite "rock" band is Steely Dan. But there& #39;d be no Steely Dan without the Beatles — and more specifically the Beatles who made Revolver.

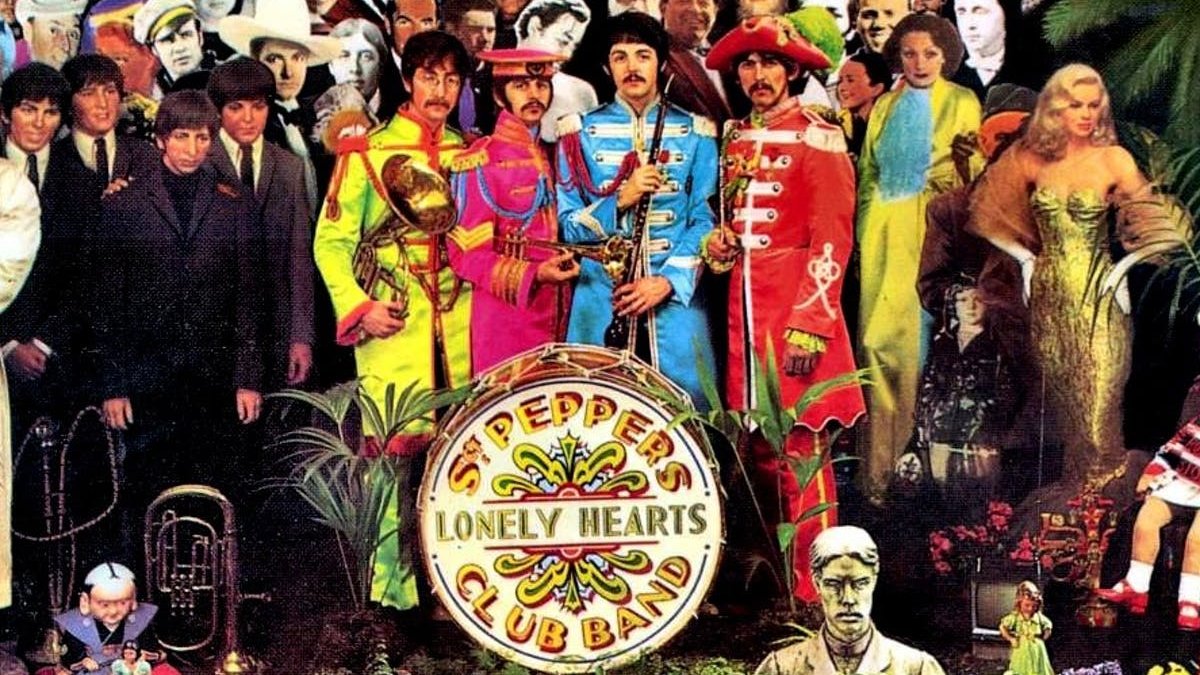

Sgt. Pepper& #39;s Lonely Hearts Club Band: Though this one has lost its critical status as the best Beatles album to Revolver, it still has "A Day in the Life," near-universally acknowledged as the peak Beatles achievement — a song that does its part for John& #39;s top-Beatle status.

But in the anticipation it generated and the zeitgeist it captured, it surely remains the most important album of all time. Ian MacDonald writes well of its laborious recording process as well as the worshipful listening (radio stations played it for days) following its release.

"Anyone unlucky enough not to have been aged between 14 and 30 during 1966-7 will never know the excitement of those years in popular culture." But in its Edwardian-military-band theme and songs like "She& #39;s Leaving Home," Sgt. Pepper& #39;s also pays tribute to the older generation.

Not that the Edwardian military band ultimately has much to do with the project, which gets labeled the first concept album, but whose concept barely extends beyond three songs. Even more so than on Revolver, each song comes off as primarily the work of an individual Beatle.

"It worked because we said it worked," John later admitted of the Sgt. Pepper& #39;s "concept," an attitude I can certainly respect. This is cultural power: the ability to not just record an album that seizes attention around the world for weeks, but dictate how people listen to it.

The Beatles managed to get the even ears of those uninterested in participating in the coming Summer of Love, having elevated rock music into artistically respectability — the quality that did the most to bring a critical backlash against Sgt. Pepper& #39;s in the decades thereafter.

As as Lester Bangs put it, "Rock and roll is not an & #39;art form& #39;; rock and roll is a raw wail from the bottom of the guts." The claim doesn& #39;t really resonate with me: by all means wail, but at least do me the courtesy of spending 50 hours in the studio doing something new with it.

Incidentally, growing up long after the Beatles& #39; heyday meant that I encountered many of their songs first as cover versions. Like most of my generation, I knew "With a Little Help from My Friends" first in the semi-intelligible rendition of Joe Cocker& #39;s: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4s8J5s_xfU0">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

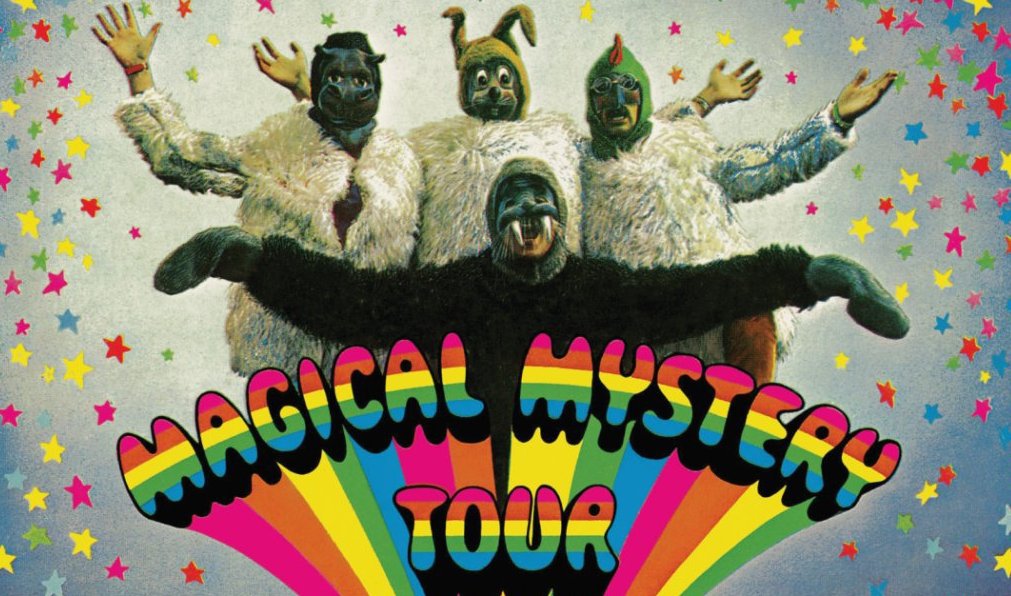

Magical Mystery Tour: Not a "real" Beatles album, but a double EP that came out as an album only in the U.S. (where labels had a history of mangling Beatles releases). It wasn& #39;t conceived as an album in the first place, but the strength of its songs eventually made it canon.

Ostensibly the soundtrack to the eponymous TV movie (about which more later) Magical Mystery Tour also contains material recorded earlier. "Penny Lane" and "Strawberry Fields Forever," two of its best known tracks, were originally meant for (but not included on) Sgt. Pepper.

This is to say that the Beatles catalog is more complicated than people (especially those who get into it at age 35) assume. Many popular songs aren& #39;t on proper albums at all — "She Loves You" and "Paperback Writer" come to mind — and I thus haven& #39;t really listened to them yet.

The only song on Magical Mystery Tour I knew very well before this week was "The Fool on the Hill," and then only in Sergio Mendes& #39; version. (It played all the time on the radio station I announced on long ago, "Magic 106.3, the Sound of Santa Barbara.") https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lFO8UgM3YVU">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

Of course I& #39;d been encountering the phrase "I am the walrus, koo koo kachoo" (apparently the "correct" rendering is "goo goo g& #39;joob") since childhood, and gathered that it signified something about the Beatles finally going around the bend due to drugs, self-aggrandizement, etc.

Startlingly, "I Am the Walrus" (which I don& #39;t remember ever hearing before) turns out not to be a particularly dated-sounding song. "Strawberry Fields Forever," another John piece, is followed by Paul& #39;s "Penny Lane," a sequence that reveals the core differences between the two.

The album& #39;s biggest surprise for me was the presence of a Los Angeles song, George& #39;s "Blue Jay Way." Despite my ignorance of the Beatles, one would think my obsession with Los Angeles (and the work of outsiders there) would& #39;ve led me to it long before now. https://twitter.com/colinmarshall/status/1113595496612786176">https://twitter.com/colinmars...

I& #39;d never even heard of Blue Jay Way itself, on which George rented a house during his visit to Los Angeles. Nor had I heard of the other "bird streets," which all together comprise one of the more prestigious sections of the Hollywood Hills. This is a house on Blue Jay Way:

Critics disagree about how good a song "Blue Jay Way" is, but I appreciate how it captures the haze (in more than one sense) of life in late-1960s Hollywood. Critical negativity is more convincing about "All You Need Is Love," the album& #39;s closer and a song everyone has heard.

"All You Need Is Love," as Ian MacDonald writes, "shows the rot setting in: a shadow of sense discernible behind a cloud of casual incoherence." And yet it makes "a transcendental statement, as true on its level as the principle of investment on the level of the stock exchange."

CINEMATIC INTERLUDE: The Magical Mystery Tour album is the soundtrack of an eponymous hourlong TV movie. The former became a hit, at least in the U.S., but the latter, still considered the Beatles& #39; biggest flop, didn& #39;t make it out of the U.K. after its first broadcast on the BBC.

I& #39;ll give the movie this: it& #39;s funnier than Help! and surely a clearer view into the band& #39;s own headspace at the time. Help! shows the Beatles under the perpetual influence of marijuana, but just before its production John and George tried an even more influential substance: LSD.

One narrative of the Beatles holds that LSD both allowed them to reach new creative heights, and instilled in them the first-thought-best-thought complacency that would ultimately bring them down. A similar story could probably be told about the late-1960s counterculture itself.

That said, today nothing in the Beatles& #39; oeuvre (that I& #39;ve heard or seen so far) seems especially disordered — or "funny," as the Queen is reported to have described the band in 1966. Magical Mystery Tour plays like a string of music videos framed by vaguely Pythonesque sketches.

But music videos as we know them today hadn& #39;t been invented in 1967, and nor, for that matter, had Monty Python. Combined, it was enough to shock the remains of the establishment — the Britain still psychologically in the Second World War — who wrote into the papers complaining.

"An underlying theme is the difficulty establishment types have in getting the Beatles to follow orders," writes Roger Ebert about the A Hard Day& #39;s Night film. "They act according to the way they feel" — and value of doing so was duly taken as axiomatic by the counterculture.

Britain (and the West) has only begun to reckon with what it lost when the old self-controlled order fell away. But the Beatles didn& #39;t cause it to happen themselves, nor did they oversee the whole decline into emotional incontinence. That would take Diana: http://blogs.britannica.com/2007/08/the-dianafication-of-modern-life/">https://blogs.britannica.com/2007/08/t...

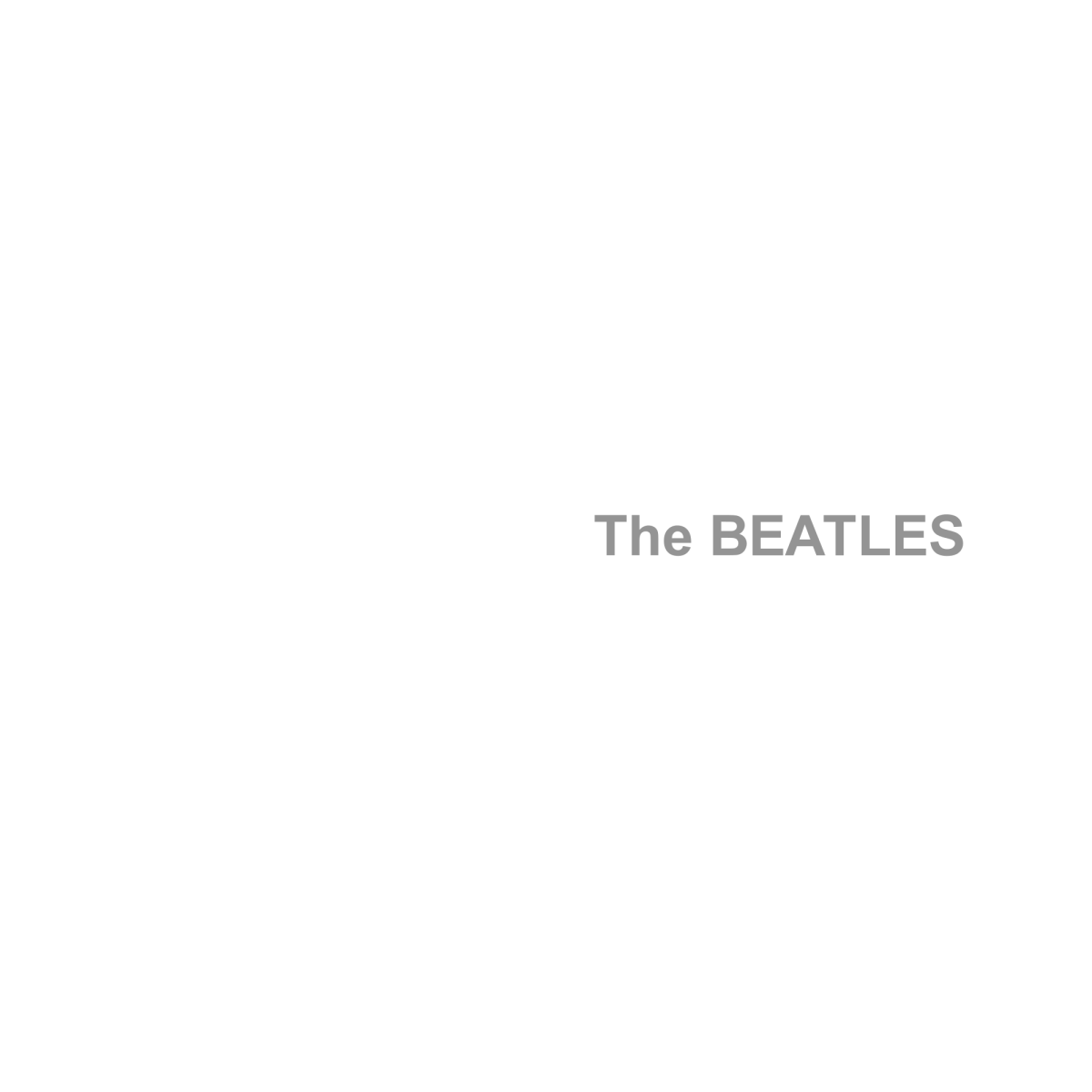

The Beatles: For all the ignorance in which I began this listening project (and which spurred me to it in the first place), I can at least say for myself that I already knew this one wasn& #39;t actually titled "The White Album" — and of its 30 tracks, surprisingly many are familiar.

I& #39;d heard "Rocky Raccoon" many times before, for instance, and in fact got a rise out of people for years by calling it my favorite Beatles song. But then, what is a favorite song if not a song you listen to more than others, even if only because Kidstar 1250 AM spun it so often?

I can& #39;t help but envision all the characters in "Rocky Raccoon" as actual anthropomorphic raccoons, perhaps because I was poisoned by Disney cartoon shows growing up, perhaps because Paul& #39;s tendency toward objective, concrete lyrics makes his songs invite literal interpretation.

In college I saw a student claymation music video made for "Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da" that just rendered the song& #39;s imagery as straightforwardly as possible: a man rolling his wheelbarrow into the marketplace, a woman putting on her makeup at home, both of them playing in a band, etc.

It comes as something of a relief to find out that "Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da" is not considered a particularly good song, at least by critics. MacDonald calls half the tracks on the album MacDonald "poor by earlier standards," their lyrics "the lazy navel-gazing of pampered recluses."

McDonald also has harsh words for songs I like better: "Few have seen fit to describe this track as anything other than a literally drunken mess," he writes of his fellow critics on "Helter Skelter," a song I& #39;d never heard before, but for Mansonian reasons had of course heard of.

"Helter Skelter" still has more fans than "Revolution 9," about which it& #39;s often claimed that "nobody has listened to it more than once." But even I& #39;ve listened to the track at least a dozen times, the first being when my dad put it on for my ninth birthday a quarter-century ago.

It took me this long to hear "Revolution 9" in context, sprawling and haphazardly quality-controlled a context though the "white album" may be. I doubt I& #39;ll give it another listen when I& #39;m done, but only because I doubt I& #39;ll listen to any Beatles song separate from its album.

"Birthday" would& #39;ve been too on-the-nose a choice for the big number nine, and besides, I also knew the song from Kidstar and its daily birthday announcements. It sounds stranger in its original context, where it now plays like a Christmas song dropped in the middle of the album.

I knew "My Guitar Gently Weeps" from a cover by the Rippingtons, whom I followed closely in high school. (It struck me as an odd name for a song.) My new Beatles knowledge now allows me to appreciate the "joke" of using a sound like George& #39;s beloved sitar: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PF8vg7v_Sgg">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

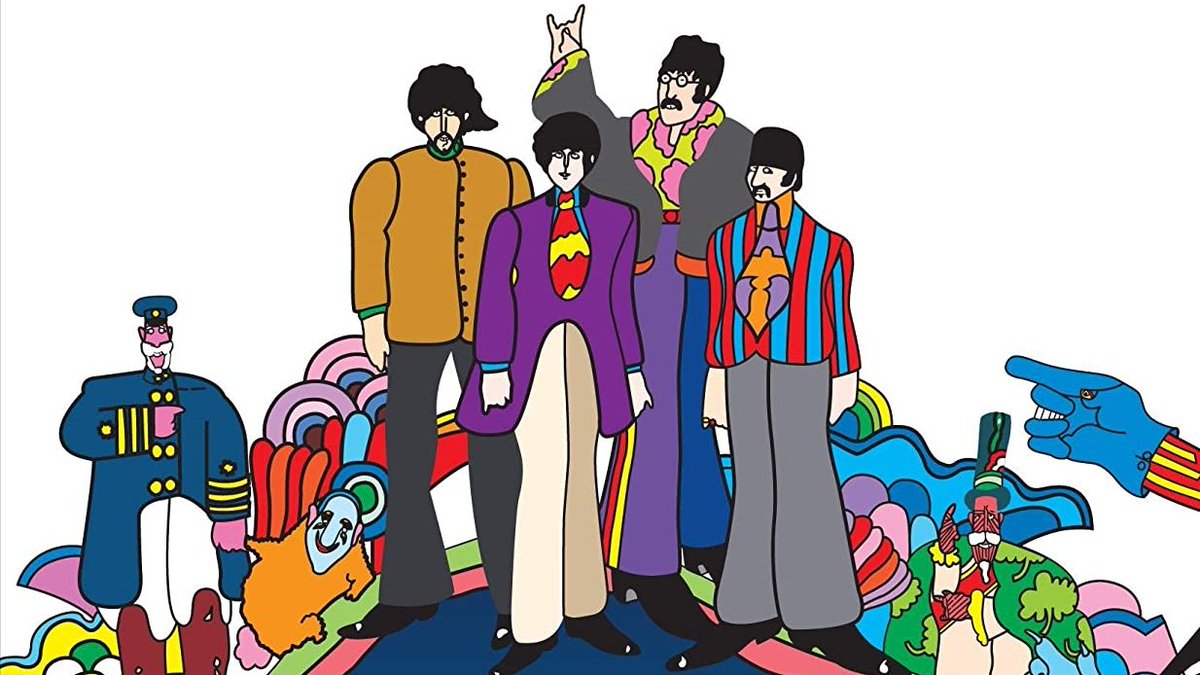

Yellow Submarine: The least essential Beatles album so far, first because, like Magical Mystery Tour, it was put together as a film soundtrack rather than as a coherent listening experience. Second, two of its songs (title track included) have already appeared on previous albums.

Only the first side contains Beatles songs at all, the second being filled by George Martin& #39;s orchestral compositions for the movie. And from what I& #39;ve read, the original Beatles numbers were offered in something of a cynical spirit, most notably George& #39;s "Only a Northern Song."

John& #39;s "Hey Bulldog" isn& #39;t bad, but in any case Yellow Submarine doesn& #39;t stand on its own. Unlike Magical Mystery Tour, which became a hit despite the corresponding movie& #39;s flop, this album exists primarily as an accessory to...

CINEMATIC INTERLUDE: ... the Yellow Submarine film, a piece of animation quite unlike any I& #39;ve seen. Whatever I& #39;d imagined a psychedelic animated film from 1968 starring the likenesses of the Beatles would be like, the real thing is even more so.

Comparing the viewing experience to a state of altered consciousness would be too easy, but it& #39;s as true of Yellow Submarine as it is of Kubrick& #39;s 2001, which had come out just two months before. (I can& #39;t imagine what either were like for those who actually watched them high.)

1968 was a different time, so they say. But then, so was 2008, the year Adventure Time first appeared as six-minute short. I still remember the incredulous reactions to it: "OMG WERE THEY HIGH OR WHAT" (as if animation could be accomplished in that state) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HzQHrxq3iyI">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

Yet Yellow Submarine does bear the traces of LSD consciousness, from the unceasing wordplay to the cast of grotesque man-animal chimeras that populate the supporting cast. I& #39;m reminded of Google& #39;s "Deep Dream" algorithm, said to produce LSD-like visions: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DgPaCWJL7XI">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

Many of Yellow Submarine& #39;s jokes reference the Beatles& #39; work. This hints at an aspect of the Beatles canon the white album& #39;s "Glass Onion" got me thinking about: “Two of the five Beatles songs mentioned in it," writes McDonald, "also contain references to other Beatles songs.”

One overarching question of this listening project is not what makes the Beatles good, but what makes them good to like — in other words, what makes them an engaging phenomenon to pursue knowledge about, to be a fan of. I suspect this self-referentiality is an essential element.

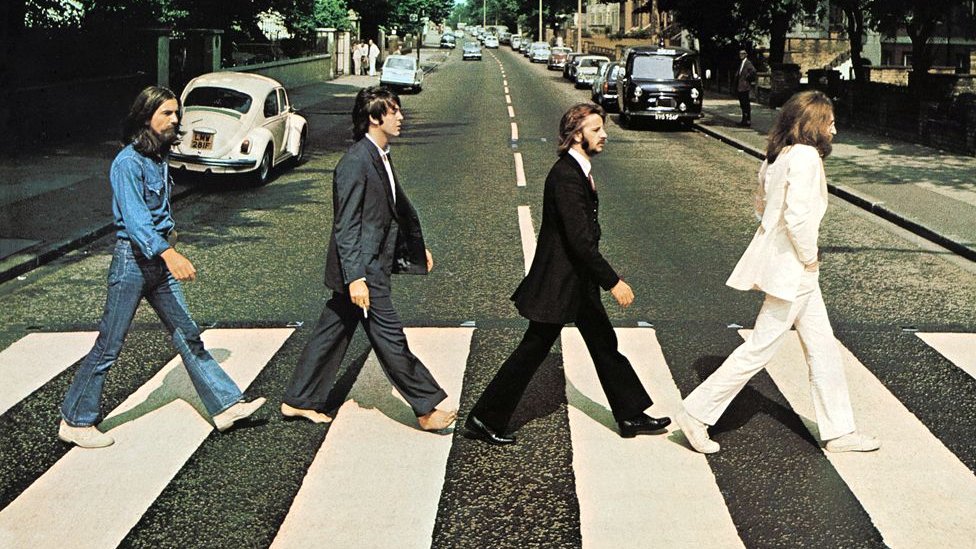

Abbey Road: An especially famous album, though I suspect mainly because of its cover. Everybody knows the image of the Beatles in the crosswalk, but I honestly wonder how many people could name many of the songs themselves, past the openers "Come Together" and "Something."

The research I& #39;ve done as part of this listening project over the past two and a half months has given me the impression that, though the Beatles may be the most popular band in human history, the average person who claims to like them still knows their body of work only vaguely.

But then, even when I& #39;d never heard any Beatles album — lo those three months ago — I knew many things about them for which I couldn& #39;t account. I knew, for example, that Abbey Road was the last album they recorded, but the second-to-last they released, though I didn& #39;t know why.

I have come to learn, however, that Abbey Road represents the end of the Beatles& #39; creative zenith, a period that opens with Rubber Soul (or thereabouts). And without this experience I never would& #39;ve known to listen to its songs for the signs of finality that now sound so clear.

Paul, it seems, was the only one holding the band together at this point, and his songs here don& #39;t hide that fact. As usual, the minor works are the most revealing: “If any single recording shows why The Beatles broke up," writes Ian MacDonald, "it is Maxwell& #39;s Silver Hammer& #39;.”

Or more palatably, there& #39;s "You Never Give Me Your Money," in which Paul "acknowledges that the dream is over,” in which "an entire era — the idealistic, innocent Sixties — is bravely bidden farewell." More bluntly, the last real song on the album is, of course, titled "The End."

Let It Be: And so we arrive at the last Beatles album, and by critical consensus the worst Beatles album. Its origins are inauspicious: planned as a back-to-basics, all-original live album, it was abandoned and infamously "re-produced" by Mr. Wall of Sound himself, Phil Spector.

John, who did his part to bring Spector to the project after the Beatles had effectively broken up, defended the re-production: "He was given the shittiest load of badly-recorded shit with a lousy feeling to it ever, and he made something of it." Indeed, it topped the charts.

George Martin articulated another view when he suggested the album carry the credit "Produced by George Martin, over-produced by Phil Spector." Almost since I began listening to music, such charges in general have irked me. There& #39;s good and bad production, but "over-production"?

Accuse a record of "over-production" and you accuse the producer, often not exactly a musician, of adding or manipulating sound in such a way as to interfere with the experience intended by the musicians — of muffling the Lester Bangsian "raw wail from the bottom of the guts."

As I& #39;ve said, I don& #39;t quite buy the value of the raw musical wail, from wherever in the guts it issues. Nor do I consider production extraneous to a song. Nick Drake came up earlier; though he composed his songs on guitar, I hear the strings added during recording as essential.

The strings Spector layered atop "The Long and Winding Road" — often Exhibit A in the evidence for Let It Be& #39;s desecration — are another matter. They sound badly dated today, but Paul himself has elsewhere been capable of the same degree of schlock, if not quite the same kind.

I don& #39;t feel the need to include in this lineup Let It Be... Naked, Paul& #39;s de-Spectorized version of the album. But I do note that it came out in 2003, a time when the notion of "straightforward indie rock" had mainstream currency — and when I was listening to 80s Hall and Oates.

On an H&O concert DVD I watched back then, one of them declares that any song that still sounds good on just an acoustic guitar is a good song. They then launch into an acoustic version of "Out of Touch" — a track I like mostly because of its production. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IWRve2CFkI8">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

But do Beatles listeners in general share these anti-Let It Be sentiments? The songs& #39; cultural impression has been made: that Beatles-themed musical film a few years ago took its name from "Across the Universe," as I suspect did a certain pottery-painting chain from "I Me Mine."

Haphazard though its making was, the album is also indirectly responsible for my own oldest Beatles-related memory: the Sesame Street song "Letter B." https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WmVd9F1fW00">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

CINEMATIC CODA: Michael Lindsay-Hogg& #39;s Let It Be documentary is known as a portrait of the Beatles in mid-dissolution. Though George attempted to leave the band during filming, the only bit of drama included in the film is him getting a quasi-lecture from Paul about his attitude.

There& #39;s actually not much more dialogue than that in the whole 80 minutes. The lack of narration and interview footage serves the whole, with its implicit story of the struggle to make music that live up to the Beatles& #39; reputation under comparatively artificial circumstances.

The initial concept has them trying to record an album on a film soundstage; later they move to the more comfortable environs of a basement recording studio, albeit a makeshift one. All the while the cameras roll, and Yoko Ono looks on from the corner like a pale ghost.

If the Let It Be movie is known for any one sequence, it& #39;s the rooftop concert — the Beatles& #39; final live performance — with which it ends. As with much in the culture, I first came to know it through Simpsonian parody, when Homer and his barbershop quartet sing atop Moe& #39;s Tavern.

That episode aired 26 years ago. Let It Be, both the album and the film, came out 50 years ago next month. From this vantage, I think I can see that the Simpsons is the only phenomenon of Beatles-comparable cultural influence that has happened — or will happen — in my lifetime.

POSTSCRIPT: I& #39;d first intended to listen only to the Beatles& #39; studio albums, but even together they don& #39;t amount to a complete (or rather, compleat) Beatles catalog experience. For that you also need Past Masters, a 1988 compilation by preeminent Beatles historian @MarkLewisohn.

Much of what intrigued me about the Beatles& #39; accomplishment in the first place was their role in inventing the album as a form in and it of itself. By definition, then, they began making music in a time before albums were albums, when the single was an even more viable product.

The list of Beatles songs issued only as singles is considerable: "She Loves You," "I Want to Hold Your Hand," "I Feel Fine," "Day Tripper," "Paperback Writer," "Hey Jude," and so on. These all appear on Past Masters, as do a couple of German-language versions and other oddities.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter