As promised, a thread on (Bavarian) German christmas bakery. & #39;Tis the season, after all. One of the oldest examples popular in southern Germany and Austria is the Kletzenbrot. Kletzen are dried pears and the rural population would add the dried pears to their bread during advent.

Any sweetness would come from the pears alone. As time went on, ingredients, such as prunes, nuts, raisins, figs and other fruit as well as honey or sugar. Sometimes it is also wrapped in a thin layer of yeast dough to keep it moist and keep the fruit on the outside from burning

Where Kletzenbrot is a thoroughly rural, peasant product, usually consumed with a glass of fruit schnapps, most traditional Christmas bakery likely has an urban/bourgeois origin, often containing once very expensive ingredients such as sugar and spices.

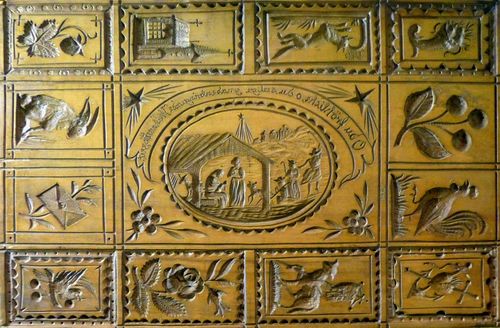

Originating in 14th century Swabia, the Springerle is also a biscuit no commonly associated with Christmas it is made from egg whites, flour, harsthorn salt and aniseed. The hartshorn salt causes the dough to rise to almost double it& #39;s size. Springerle are not made with cutters

but with molds carved from pear wood, with a great variety of motives, though it is thought hte oldest motives were religious, taken from motives of the host. The Springerle, whose name means "little jumper", possible because the dough is "jumping up" during baking.

Springerle aren& #39;t only for consumption but also for decoration, often pierced to allow for a ribbon and also painted with food colouring they are great as christmas tree ornaments and can be stored and re-used once they have dried out entirely.

Another old, famous Christmas buscuit commonly produced with molds is Spekulatius, probably originating in The Netherands and Belgium, they are a German Christmas staple. A spiced biscuit dough is the most popular but there are also varieties like almond or butter Spekulatius.

Due to the ingredients, Spekulatius could be comparatively expensive until after WWII and were thus considered very exquisite biscuits.

Another traditional and famous item in Christmas baking is the Stollen, a cake baked in a shape supposed to represent the swaddled baby Jesus

Another traditional and famous item in Christmas baking is the Stollen, a cake baked in a shape supposed to represent the swaddled baby Jesus

The earliest mention of Stollen as a baked good dates from 1329 when the then bishop of Naumburg obliged the city& #39;s bakers (amongst others tithes) to deliver two long white breads called Stollen for Christmas to his court. The earliest recipe we might recognise today dates from

1730. Today it is a very rich cake with strict regulations as to the ratio of ingredients. There are of course also varieties of Stollen, what they have in common is a buttery, eggy, rich yeast dough. The Christstollen is the most common variety, containing raisins, currants,

candied peel and covered generously in confectioner& #39;s sugar. Other varieties are the poopy seed Stollen (sometimes with a streusel topping), Quarkstollen, Marzipanstollen, almond Stollen, nut Stollen and Butterstollen

The City of Dresden is considered the Stollen capital of Germany and the Dresdner Stollen enjoys PGI status. During dvent there is the famous Dresden Striezelmarkt which has had that name since 1548, "Striezel" is the iddle High German word for Stollen and still used in Saxony.

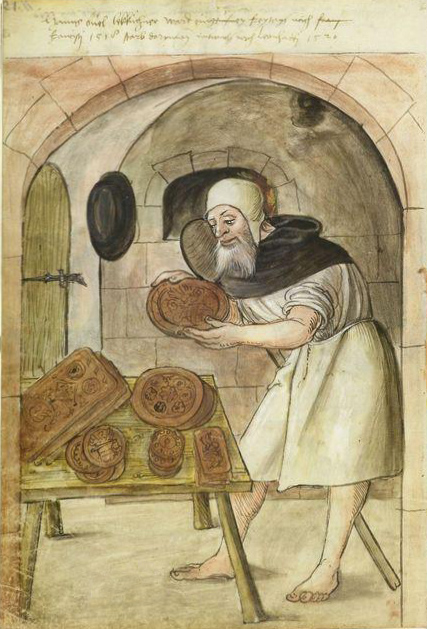

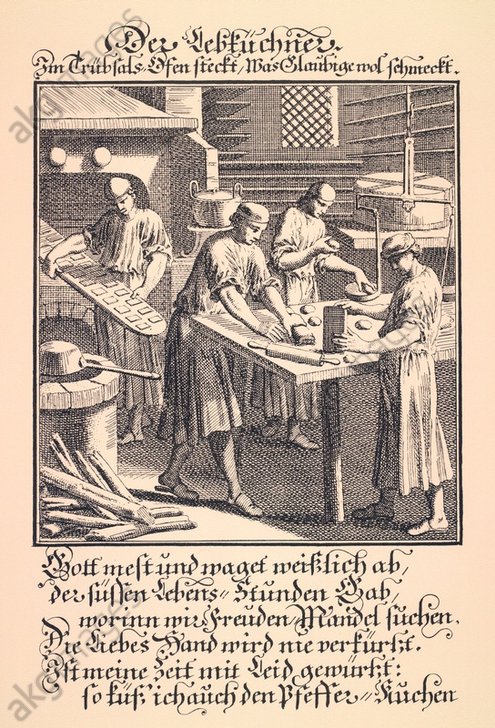

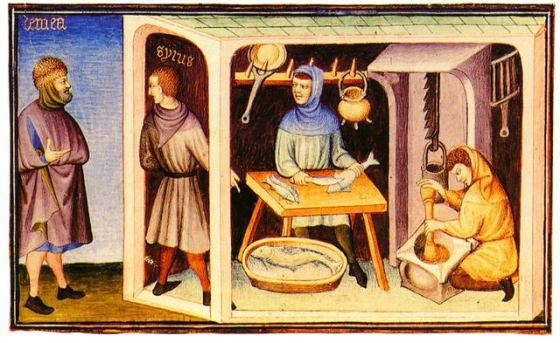

To continue with the journey to German Christmas bakery, today I& #39;ll talk about an iconic baked good, variations of which are known all over Europe: Lebkuchen. Spiced cakes with honey were already known in ancient Egypt and Rome. Lebkuchen as we know it today probably originated

In the Belgian city of Dinant, where the Couque de Dinant is still sold. From there they made their way to Aachen and further into Germany. Initially they would be baked in monasteries and abbeys and eaten with beer during fasting or handed out during famines or to the poor.

The earliest mention of "Pfefferkuchen" (pepper cake) dates from Ulm in 1296. In Nuremberg the earliest mention is from the 14th century. The longest Lebkuchen traditions exist in trade centers due to the spices needed, such as Cologne, Ulm, Basel, Augsburg and Nuremberg.

Over time the cities allowed guilds of Lebzelters, Lebküchlers, Pfefferküchnersetc to be established, often closely aligned or combined with honey- and wax processing trades such as chandlers. In Catholic hagiography they share a patron saint in Ambrose of Milan

Unlike today, Lebkuchen were not exclusively associated with Christmas but were often sold in places of pilgrimages as a souvenir to take home. That tradition is still alive in places such as Mariazell in Austria. Lebkuchen were also part of festivities like weddings.

Gnerally, there are two kinds of Lebkuchen: brown Lebkuchen, containing a relatively high proportion of flour resulting in a kneadable, formable dough to create Printen, Lebkuchenherzen, ginger bread houses, christmas tree ornaments...

The other kind is the Oblatenlebkuchen. That dough contains very little to no flour but high amounts of nuts or seeds and sugar. The higher the nut content, the higher the qualits of the Lebkuchen. The batter is piped onto a thin, host-like wafer before baking which prevents the

Lebkuchen from sticking. They are traditionally left unglazed (Weiße Lebkuchen/white Lebkuchen) or they are glazed with sugar or dark chocolate. In both varieties the honey, spices and flour mix are traditionally stored for weeks or months to allow for the flavours to mature.

Nuremberge Elisenlebkuchen, Thorner Lebkuchen (Toruńskie pierniki) go back to the 13th century when Torún was part of the State of the Teutonic Order, Pulsnitzer Pfefferkuchen or Neisser Konfekt or Coburger Schmätzchen

The introduction of baking powder in the 19th century broadened the range of Lebkuche, leading to airier more cake-like varieties, like Berliner Brot or my mum& #39;s delicious Feine Schnitten.

Pulsnitzer Pfefferkuchen are available all year round and so is "Magenbrot" (stomach bread), a glazed variety, which is a traditional fairground treat and the spices are supposed to be beneficial to the digestive system.

Right, so that was my bit on Lebkuchen. If you want to try baking some at home, I& #39;ll gladly ask my mum for the recipes. I hope you& #39;ve enjoyed the thread so far. There is still more to come of course. Marzipan-based bakery, for example and all the biscuits...

Welcome back to my small guide to German Christmas bakery. I hope you& #39;re still up for some more treats. This time I& #39;m talking about another staple that was once astronomically expensive as sugar and almonds were a great luxury until sugar became cheap with extracting it from

sugar beets. Marzipan is available all year round but also plays a big part in Christmas bakery as an ingredient in Stollen, Lebkuchen, Dominosteine and biscuits. But also as a confectionary of its own. I want to focus on two specialties associated with Frankfurt am Main,

the Bethmännchen and the Brenten. Marzipan originated in Persia and is first mentioned in Europe in 13th century Venice. As the ingredients, sugar and almonds had to be imported in Northern Europe, two port cities in the then Hanseatic League became synonymous with Marzipan in

Germany: Lübeck and Königsberg (Kaliningrad), the term "Marzipan" can be found in Lübeck guild scrolls as far back as 1530. Initially, the Marzipan would also be used with molds like Spekulatius or to sculpt forms and in Nuremberg would be given as a present in rich households.

The most famous German producer of Marzipan is Niederegger, which was founded in 1806 in Lübeck. Now to the Bethmännchen, they are named for the prominent 19th century banking family Bethmann but are likely older. It is a dough of marzipan, sugar and rosewater to which 3 almond

halves are stuck, then they are given an egg yolk wash and are put into the oven to be "flamed", to get a golden touch.

The older Brenten are essentially made from the same dough though the sugar may be replaced with honey. They have been known in Frankfurt since the middle ages and the romantic poet Eduard Mörike described the laborious process of making them in the poem "Frankfurter Brenten"

unlike the Bethmännchen, the Brenten dough is pressed into molds before being decorated and flamed in the oven.

Another marzipan confection associated with Christmas but available all year round is the marzipan potato, a ball of marzipan and confectioner& #39;s sugar rolled in cocoa and sometimes decorated with three incisions to give them the look of an oven spud with the peel split open.

In some Konditoreien/cake shops there is a large marzipan potato, which is a sponge filled with nougat or ganache wrapped in marzipan

That& #39;s it for today, I hope you enjoyed the short sojourn into the marzipan side of Christmas treats in Germany. Next up: Biscuits, macaroons etc

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter