Not that I really think anything said on this hellsite will matter in the end, since it’ll likely all be lost in 10 years, but I said I would talk about parables and I’m hopped up on migraine meds so let’s do this. https://twitter.com/Delafina777/status/1192695295714316288">https://twitter.com/Delafina7...

I think I& #39;m gonna do this in a structure that resembles a comb: that is, a “spine” of a main line of discussion, and “teeth” coming off it to drill down into details, because it& #39;s my Twitter and I& #39;m feeling experimental.

Spine tweets will be numbered and have an image, while teeth tweets will have the number of the spine tweet they come off of along with an X (and no image unless it’s necessary). If I want to elaborate on a thought later, I’ll use that method.

1 First off, disclaimers/assumptions/shorthand. I don’t necessarily believe these things to be true, but I’m also not interested in getting in the weeds about them (you’re free to have a discussion about them elsewhere, but don’t derail mine):

2 WARNING: Do not proselytize in my mentions or you’re gonna catch a block. I’m Jewish for a whole host of reasons, none of which are that I just don’t understand Christianity well enough or I’d be Christian. The same is true of most of my kin.

3 I’m ambivalent about the endeavor to “reclaim” Jesus as a Jew. While it’s intended to promote greater understanding and shalom between Jews and Christians, the actual result of it seems to just be increased Christian appropriation of post-Jesus Judaism. But I’m still gonna try.

4 I think there’s a significant problem with how Christians in general understand the parables, and with how Christian clergy tend to preach them. The parables get treated as if they’re Aesop’s fables: allegories that have a single, straightforward moral.

5 The flattening/banalization of parables actually starts with the gospels themselves: Luke immediately attaches a moral to each—often BEFORE relating the story, which is a crime against narrative—and Matthew obsessively insists EVERYTHING is somehow a fulfillment of prophecy.

6 I believe that to hear them properly, they actually need to be taken out of the gospel-writers’ explanatory context, which wouldn’t have been available to their original audience. I’m not saying don’t read it ever. I’m saying start with JUST the parable.

7 So, I think there are a number of things one should do—or, more often, NOT do—while hearing/reading these stories in order to hear them as their original audience would have heard them.

8 In summary, treat them FIRST as:

-STORIES

-Not allegories (esp retroactive ones)

-Not answer-providers but question-raisers

-challenging

-arising out of, not against, their Jewish context

-STORIES

-Not allegories (esp retroactive ones)

-Not answer-providers but question-raisers

-challenging

-arising out of, not against, their Jewish context

9 First: The parables are, first and foremost, stories a Jewish teacher was telling to a Jewish audience. They had to work on their own, as self-contained STORIES, to be comprehensible to the audience. That’s how I’m approaching them.

10 Second: As an extension of this, listeners and preachers should resist an immediate move to allegory, in which each element in a story must stand for something specific outside the story, and the story requires a key to understand. Allegory is fine, but don’t *start* there.

11 Third: We should look at them as stories intended to raise questions, because, again, that’s how the form works in its cultural context. Jewish parables don’t exist to be comforting and simple. They exist to challenge and often, to indict.

13 Finally, on that difficulty: there’s a trend among Christian clergy/writers who know enough about Jewish parables to get they& #39;re challenging but want to hold on to the familiar, traditional meaning of the parable to make a certain homiletic move, which is A Problem.

14 That move is: if the Hallmark meaning is the one they want to stick with, but they know that the parables were supposed to challenge the audience, then the Hallmark meaning must have been the one that was challenging to the original audience.

15 Thus, if The Prodigal Son is a parable about how God is compassionate toward the repentant sinner, then Jesus’s Jewish audience must have found the idea that God is compassionate toward people who’ve screwed up challenging.

16 This ties into a broader trend in which Jesus is defined over and above his Jewish context. By this line of thinking, if Jesus was preaching good news to the poor, the rabbis must have had contempt for the poor and been preaching good news to the rich.

17 So, what IS a parable? In English, it’s a story that parallels or compares things—a story that is somehow connected to a real-world situation in a way designed to make a point about that situation.

18 In Hebrew, it’s a mashal, which actually comes from the root for “rulership.” It can mean a comparison, and is often used in the sense of “cautionary tale” (e.g. 1Ki 9:7 and Ps 69:12).

19 Neither a secret tale with a hidden meaning nor a transparent story with a clear-cut moral, the mashal is a narrative that actively elicits from its audience the application of its message—or what we would call its interpretation.” https://www.academia.edu/37427742/David_Stern_The_Rabbinic_Parable_and_the_Narrative_of_Interpretation_in_Michael_Fishbane_ed._The_Midrashic_Imagination_Albany_SUNY_Press_1992_78-95">https://www.academia.edu/37427742/...

20 What actually counts as a parable in the NT doesn’t seem subject to any sort of consistent agreement. Are there 38? 46? 22? Most biblical scholars seem to agree that there aren’t any parables in John, but beyond that? Nothing.

21 I’m going to use this since it seems pretty comprehensive and clear. https://www.slideshare.net/heartnoi2k/parables-of-jesus-30420415">https://www.slideshare.net/heartnoi2...

22 For each parable I talk about, I’m going to talk about a handful of traditional interpretations, then how I think a first-century Jewish audience would have heard it.

So, I& #39;m going to go get some more tea, add some notes to some of these tweets, and then talk about the Pharisee and the Tax Collector.

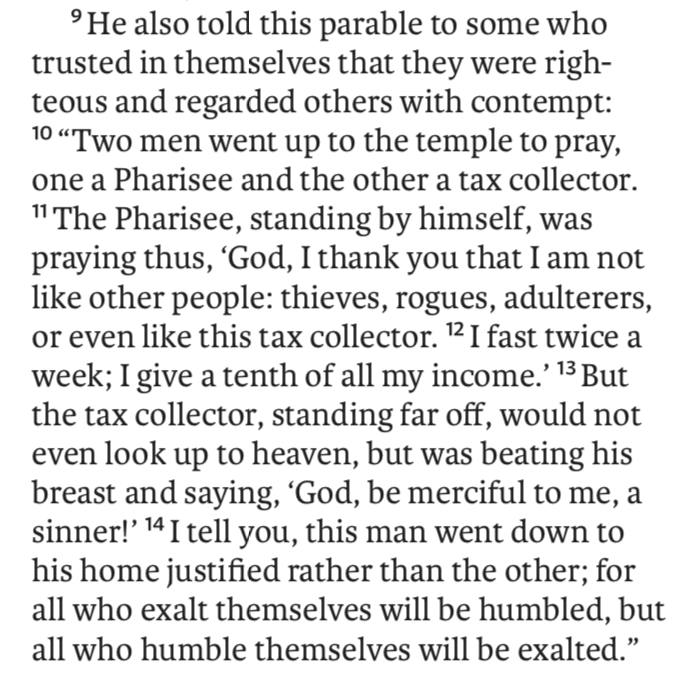

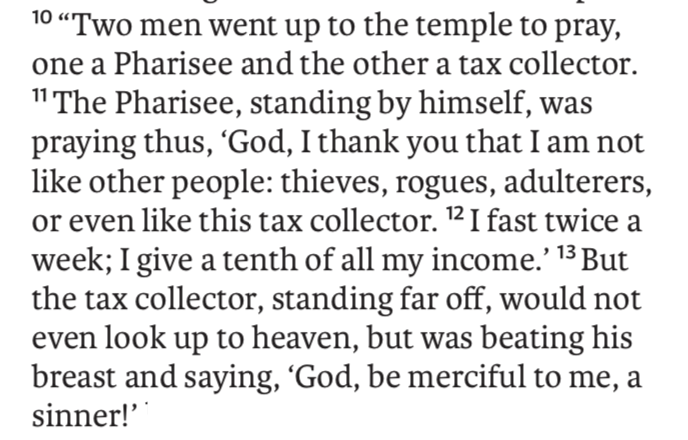

A1 Okay, so, here& #39;s the Pharisee and the Tax Collector. It only appears in Luke (18:9-14), so you can use this version from the Jewish Annotated New Testament or check your translation of choice.

A2 I think Luke is doing glossing both at the beginning (overtly) and the end (crediting it to Jesus), here. So here& #39;s the *story* without commentary.

A3 So, we all know the common interpretation of this one, right? If your prayer is all about how great you are in comparison to everyone else, God isn& #39;t gonna like it? (And also, self-evidently, you& #39;re kind of a dick.)

A4 That& #39;s fine, I suppose. I mean, it& #39;s pretty shallow and pretty obvious and I& #39;m sort of surprised anyone thought you needed to be God Himself Walking The Earth to come up with it, but sure.

If only preachers had stopped there.

If only preachers had stopped there.

A5 Unfortunately, Augustine had to jump right in there and be gross about the whole thing, practically as soon as Christianity got off the ground.

A6 This is what I mean when I say that immediate moves to allegory are a problem. Suddenly the story of two individuals that& #39;s probably supposed to prompt individual self-examination is about *groups.* Jews vs. Gentiles.

A7 The inability to hear the story in the way its original audience would have, again, is there already in Luke. Some pastors will acknowledge that Jews at the time would have assumed the Pharisee was a good dude and hated the tax collector, and that& #39;s where the pop comes in...

A8 ...but the ability to hear it that way is already eroded by Luke, who never met a tax collector who wasn& #39;t trying to be a decent guy (3:12, 7:29, 15:1, 5:29-30, 19:2) and never met a Pharisee who wasn& #39;t an asshole.

A9 So Christians are already primed to prefer tax collectors to Pharisees. And so, in exegesis and homiletics, the tax collector becomes a representative for the *powerless* and marginalized.

Of course, I& #39;ll note that this comes from a book that& #39;s used as a textbook in many seminaries, and--as far as I can tell--is seen as a progressive textbook rather than a conservative one. He& #39;s still gonna take a swipe at the gays tho.

A10 And this provides a comfortable reading for progressive Christians--the Pharisee is conservative Christians, who look down on "tax collectors" like gay people, who aren& #39;t actually particularly sinful and aren& #39;t hurting anyone else.

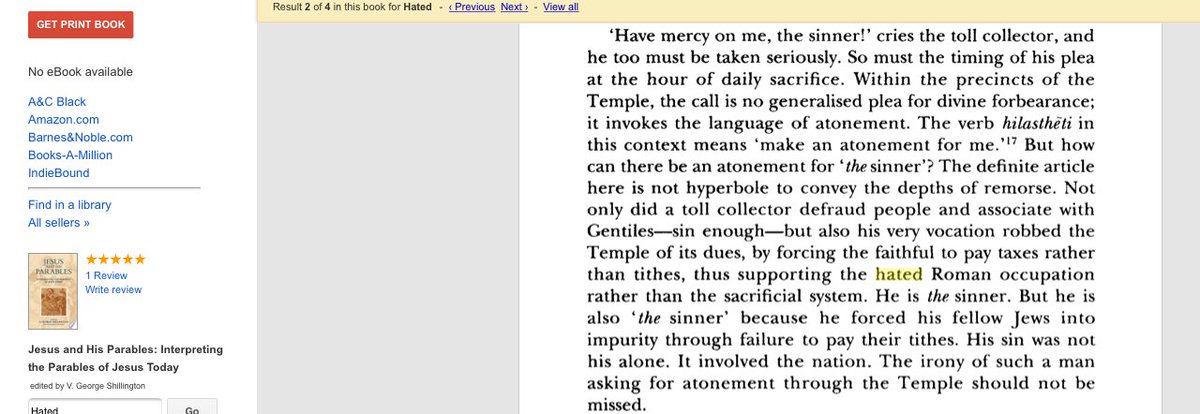

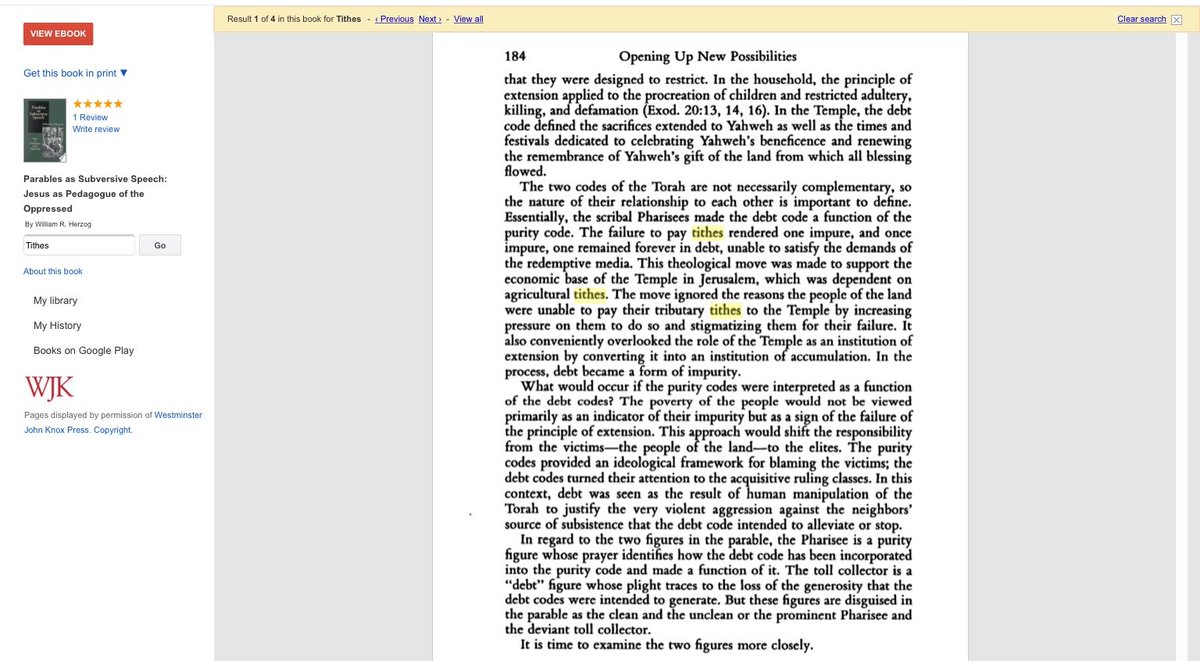

A11 Then, we have some historical... theorizing. One couldn& #39;t pay both Temple tithes and Roman taxes--and, oh yes, "associating with Gentiles" was a sin. No sources for this statement are cited--I guess the Holy Spirit gives you detailed historical knowledge or something.

A12 Additional history includes the "fact" that the Pharisees participated in collecting tithes for the Temple, and that they& #39;d changed the laws of ritual purity so that being in debt made one ritually impure. No sources are cited.

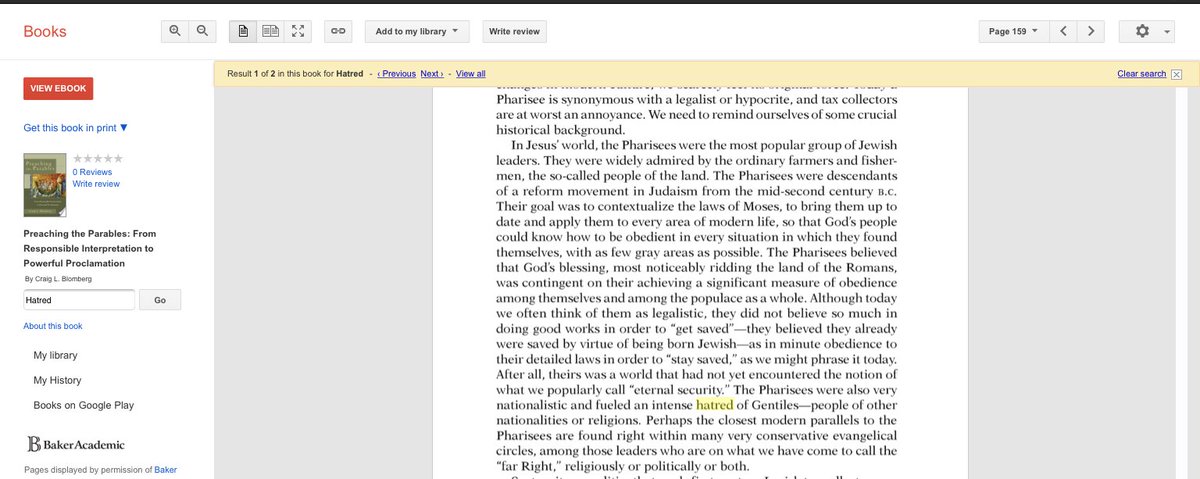

A13 And then we& #39;ve got that the Pharisees were intensely nationalistic and encouraged their fellow Jews in an intense hatred of Gentiles. Yet again, no sources are cited. We just have... magical Christian knowledge of Second Temple Judaism.

A13x A big part of this comes from retrojecting later rabbinic commentary backward onto the Pharisees. In this case, specifically, a blessing known as shelo asani.

But before we get there, we need to talk about the Talmud.

But before we get there, we need to talk about the Talmud.

A13x Specifically, we need to talk about why Christians prooftexting ANYTHING from the Talmud to "prove" things about the Pharisees, or any Jews of Jesus& #39;s time, is dangerous, likely inaccurate, and generally a bad idea.

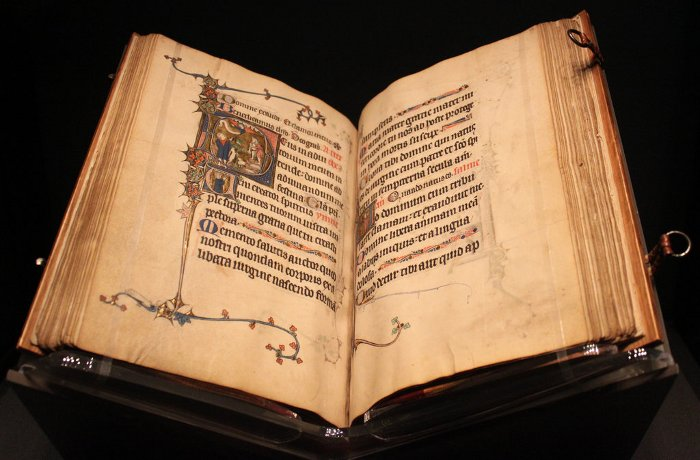

A13x I& #39;m not going to go into a ton of detail about what the Talmud IS, since it& #39;d take forever and smarter people than I have already done it. But I am going to talk a bit about the nature of it.

The Talmud is not a law book, not a story book, not a history book--it& #39;s its own genre. There really isn& #39;t anything quite like it.

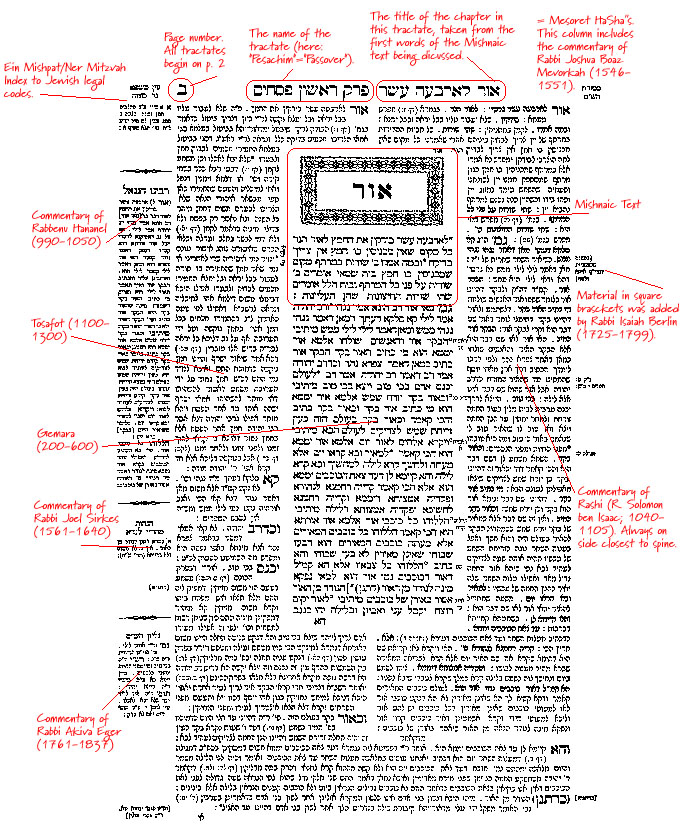

First and foremost, it& #39;s commentary on commentary on commentary. Here& #39;s a page, diagrammed. (From here: http://www.mesacc.edu/~thoqh49081/handouts/talmudpage.html)">https://www.mesacc.edu/~thoqh490...

First and foremost, it& #39;s commentary on commentary on commentary. Here& #39;s a page, diagrammed. (From here: http://www.mesacc.edu/~thoqh49081/handouts/talmudpage.html)">https://www.mesacc.edu/~thoqh490...

A13x By the way, that small center bit? That& #39;s Mishnah, which is itself essentially a commentary on Torah (a practical working-out of how to actually follow the precepts in Torah--it& #39;s a bit more complicated than that, but).

A13x Put another way, this is a *record* of debates, some of which probably actually happened, and some of which clearly DIDN& #39;T happen because they& #39;re between rabbis who lived in different centuries and/or different parts of the world.

A13x In Judaism, we argue with dead people a lot. Minority opinions, rather than being ignored/buried/erased, are preserved. In cases where it& #39;s a question of law or practice--where people need to know what to DO--usually there& #39;s a winning/majority/normative opinion.

A13x In cases where it& #39;s a question of the nature of something, theology, belief, etc. it& #39;s often unresolved because it doesn& #39;t NEED to be resolved. Judaism is about practice over belief.

A13x It goes some fascinating places, too. Like in a section known as the Oven of Akhnai. Like so many of the bits of Talmud that go to radical places, this one starts out very mundane: the rabbis are arguing over whether or not an oven is kosher. But then...

A13x

Rabban Gamaliel: It& #39;s not kosher.

Rabbi Eliezar: It IS kosher! If I& #39;m right, let this carob tree prove it.

Carob tree: *jumps out of the ground and runs away, presumably because it doesn& #39;t want to be involved*

Other rabbis: my dude, trees are irrelevant to this debate

Rabban Gamaliel: It& #39;s not kosher.

Rabbi Eliezar: It IS kosher! If I& #39;m right, let this carob tree prove it.

Carob tree: *jumps out of the ground and runs away, presumably because it doesn& #39;t want to be involved*

Other rabbis: my dude, trees are irrelevant to this debate

A13x

Rabbi Eliezer: It& #39;s kosher! If I& #39;m right, let this stream prove it.

Stream: *flows backwards*

Other rabbis: Um, streams are not legal experts, so whatevs.

Rabbi Eliezer: If I& #39;m right, let the walls of the house of study prove it.

Walls: *start to fall inward*

Rabbi Eliezer: It& #39;s kosher! If I& #39;m right, let this stream prove it.

Stream: *flows backwards*

Other rabbis: Um, streams are not legal experts, so whatevs.

Rabbi Eliezer: If I& #39;m right, let the walls of the house of study prove it.

Walls: *start to fall inward*

A13x

Rabbi Yehoshua: um, excuse me, SCHOLARS are talking here

Walls: *are now stuck in a leaning position because they don& #39;t want to get on the wrong side of either rabbi*

Other rabbis: My dude, it& #39;s 5 to 1, let it go, you lost

Eliezar: Fine. GOD, who& #39;s right?

Rabbi Yehoshua: um, excuse me, SCHOLARS are talking here

Walls: *are now stuck in a leaning position because they don& #39;t want to get on the wrong side of either rabbi*

Other rabbis: My dude, it& #39;s 5 to 1, let it go, you lost

Eliezar: Fine. GOD, who& #39;s right?

A13x

God: Eliezer is right.

Other rabbis: ...5 to 2.

And they go with the majority interpretation.

Anyway, this is a digression, but there& #39;s all kinds of fascinating stuff in there.

God: Eliezer is right.

Other rabbis: ...5 to 2.

And they go with the majority interpretation.

Anyway, this is a digression, but there& #39;s all kinds of fascinating stuff in there.

A13x The point is, it& #39;s massive, and it& #39;s a record of *debates*, not just winning opinions. So there& #39;s beautiful stuff, and there& #39;s very ugly stuff. Antisemites LOVE going hunting in the Talmud because you can find rabbis saying unpleasant shit about Gentiles, women, etc.

A13x That& #39;s the thing about Jewish history, though. We don& #39;t usually sanitize it. It& #39;s always been easy for people who want to paint us in a negative light (including the NT authors) to find ammunition from our own writings.

A13x And that& #39;s because self-criticism is basically a Jewish obsession. Most of our writings are us yelling at ourselves. The stories of our founding family focus as much on their faults as their virtues.

A13x We decided that for an entire third of the Tanakh, we were going to preserve the writings of our most pissed-off internal critics. So yeah, you want God supposedly saying very negative stuff about Jews? We kept ALLLLL that stuff.

A13x Similarly, the Talmud doesn& #39;t pull any punches when it comes to certain rabbis saying ugly things.

But I submit if you& #39;d recorded all the debates of, say, the early Church Fathers, you& #39;d find as bad or worse.

But I submit if you& #39;d recorded all the debates of, say, the early Church Fathers, you& #39;d find as bad or worse.

A13x Because for us, authority doesn& #39;t rest in any one voice. The debate ITSELF is holy.

But that makes it very easy for Christian commentators who want to "prove" something about what The Jews believe to go pick through the Talmud and find a quote.

But that makes it very easy for Christian commentators who want to "prove" something about what The Jews believe to go pick through the Talmud and find a quote.

A13x And sometimes, it& #39;s even normative practice at some point in time. The shelo asani blessing is something Orthodox Jews still say.

As part of their morning blessings, Orthodox men thank God for not making them women or Gentiles (along with a whole host of other things).

As part of their morning blessings, Orthodox men thank God for not making them women or Gentiles (along with a whole host of other things).

A13x I& #39;m not going to defend it--I think it& #39;s awful, and the rest of Judaism has done away with it--but I am going to give it context. Women are *exempt* from time-bound commandments in Judaism, because the rabbis figured they had enough to do with raising kids.

A13x And somewhere along the line, "You don& #39;t HAVE to do this" became "You SHOULDN& #39;T do this."

So Jewish men took to thanking God for the obligation/opportunity to fulfill more commandments. Women don& #39;t have to, non-Jews don& #39;t have to.

So Jewish men took to thanking God for the obligation/opportunity to fulfill more commandments. Women don& #39;t have to, non-Jews don& #39;t have to.

A13x Like I said, I don& #39;t like it, and I& #39;m not going to defend it. But it& #39;s VERY easy to overstate what it means. And in any case, it& #39;s a later practice. There& #39;s zero evidence it was something said in Jesus& #39;s time period at all, let alone normatively.

A13x So to search the Talmud, rabbinic Jewish liturgy, medieval writings, etc. for "proof" of what the Pharisees or any Jews of Jesus& #39;s time thought or did is a risky endeavor.

A13x There& #39;s some discussion in there about what the sages of the time said or did, but the Talmud& #39;s cheerful disregard for the normal progression of time makes parsing it for historical information nearly impossible for anyone who& #39;s not super-well-versed.

A13x And proof-texting from it to make the Pharisees look bad in order to make Jesus look good is easy enough that anyone who can use a search function can do it. Doesn& #39;t mean it& #39;s accurate.

A13x And I& #39;d also refer anyone who& #39;s tempted to Krister Stendahl& #39;s guidelines: https://twitter.com/Delafina777/status/1155991086856204290">https://twitter.com/Delafina7...

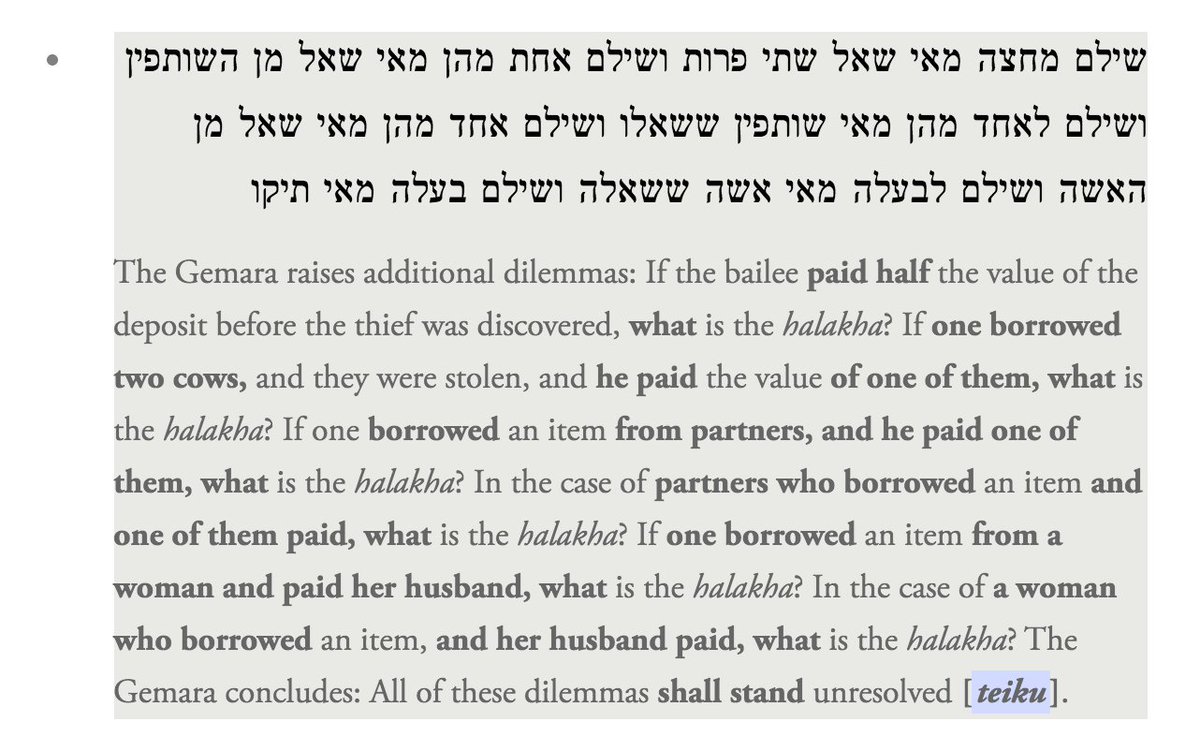

A13x Oh, and btw, even in questions of practice, sometimes the rabbis decide they& #39;re not going to decide. Meet the term "teiku," which means, basically:

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🙃" title="Upside-down face" aria-label="Emoji: Upside-down face">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🙃" title="Upside-down face" aria-label="Emoji: Upside-down face">

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter

" title="A13x Oh, and btw, even in questions of practice, sometimes the rabbis decide they& #39;re not going to decide. Meet the term "teiku," which means, basically:https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🙃" title="Upside-down face" aria-label="Emoji: Upside-down face">" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

" title="A13x Oh, and btw, even in questions of practice, sometimes the rabbis decide they& #39;re not going to decide. Meet the term "teiku," which means, basically:https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🙃" title="Upside-down face" aria-label="Emoji: Upside-down face">" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>