Can we adapt to environmental change?

How important is surface water to the economy?

I make progress on these questions in "The Scope for Climate Adaptation: Evidence from Water Scarcity in Irrigated Agriculture"

Paper: https://www.nickhagerty.com/research

[THREAD]">https://www.nickhagerty.com/research&...

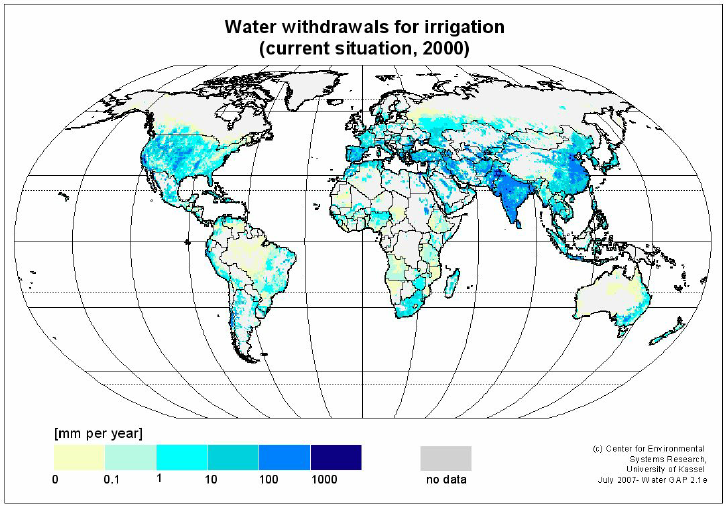

Climate change is going to wreak havoc on water supplies around the world.

Droughts, floods, more rain, less snow, glaciers disappearing, runoff coming at the wrong time.

We’re seeing plenty of this already

Droughts, floods, more rain, less snow, glaciers disappearing, runoff coming at the wrong time.

We’re seeing plenty of this already

But what is this going to mean in terms of economic impacts? How big of a deal is it?

Especially for the 42% of global crop production that relies on irrigation?

So far we don’t have a lot of empirical evidence on surface water.

Especially for the 42% of global crop production that relies on irrigation?

So far we don’t have a lot of empirical evidence on surface water.

We also don’t have a great handle on adaptation in general.

There’s good evidence on how things like hot weather affect us today. But what if that hot weather becomes the new normal?

We don’t really know how much we can adapt to environmental change in the long run.

There’s good evidence on how things like hot weather affect us today. But what if that hot weather becomes the new normal?

We don’t really know how much we can adapt to environmental change in the long run.

This paper does two things.

First, I estimate the effects of LONG-RUN surface water scarcity in irrigated agriculture.

Second, I estimate the effects of SHORT-RUN scarcity in the same setting -- so I can compare them and learn something about adaptation.

First, I estimate the effects of LONG-RUN surface water scarcity in irrigated agriculture.

Second, I estimate the effects of SHORT-RUN scarcity in the same setting -- so I can compare them and learn something about adaptation.

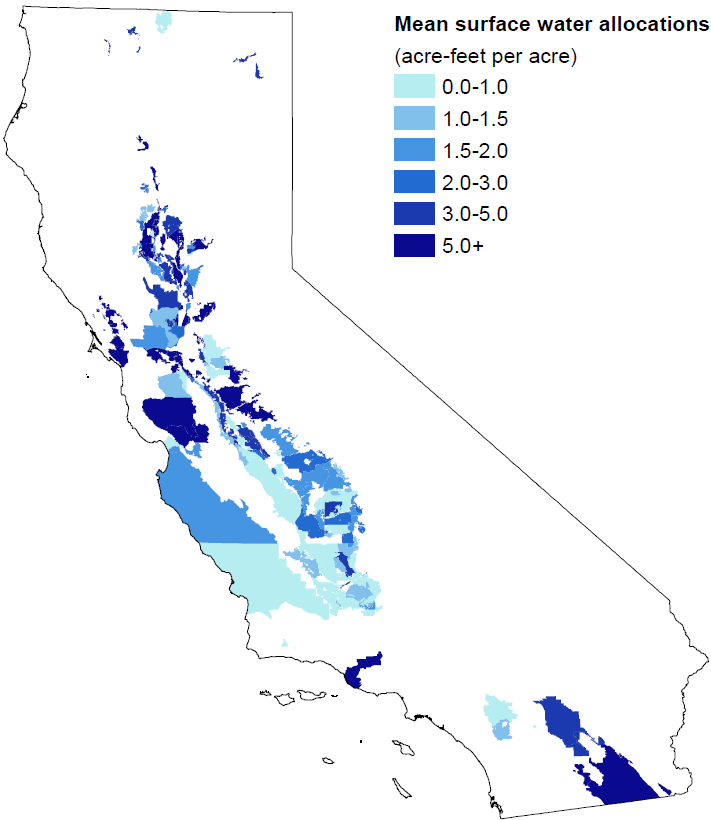

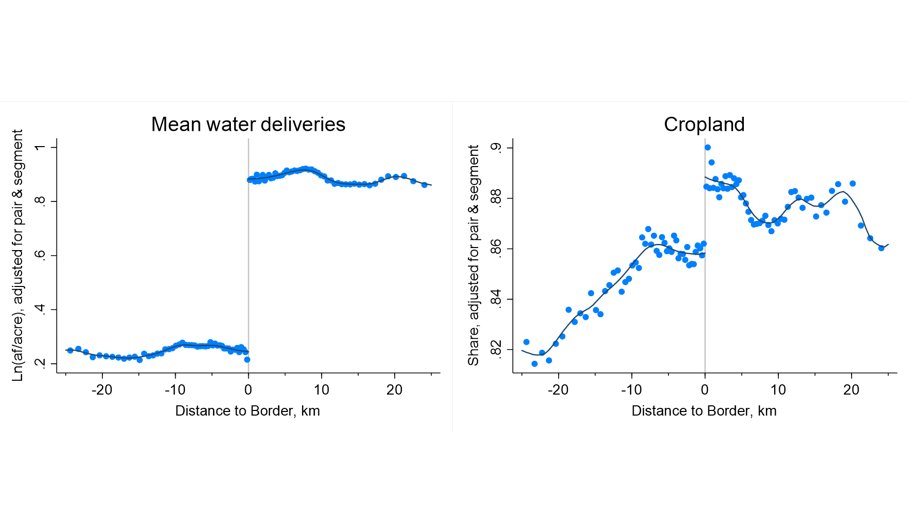

To get at long-run water scarcity, I use quirks of institutional history in California that create spatial discontinuities in average water supplies.

Basically, the Central Valley is divided up into 100& #39;s of local water districts, and they all have different water entitlements.

Basically, the Central Valley is divided up into 100& #39;s of local water districts, and they all have different water entitlements.

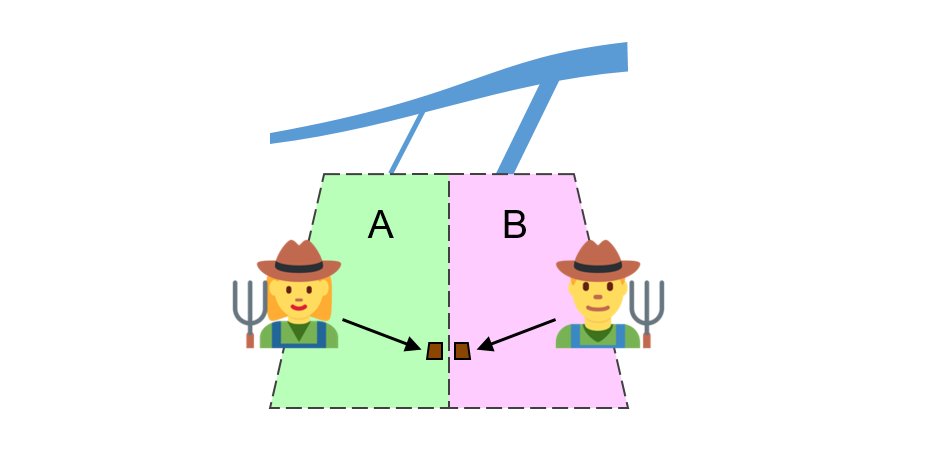

This means I can zoom in around the boundaries between neighboring water districts and compare farms just across the border from each other.

These farms look very similar -- same land, soil, climate -- except that one side has been getting a lot more water for a long time.

These farms look very similar -- same land, soil, climate -- except that one side has been getting a lot more water for a long time.

This is a new research design for measuring climate-related impacts, and it gets around a lot of drawbacks of previous approaches.

Now, there are also year-to-year fluctuations in water supplies driven by weather. For short-run effects, I compare farms across wet and dry years.

Now, there are also year-to-year fluctuations in water supplies driven by weather. For short-run effects, I compare farms across wet and dry years.

Lack of data on water use has been a big constraint to research. I get around this by putting together a big new dataset covering all wholesale-level water use in California.

(This took me months & months and I want other people to benefit. Check back soon for a public release!)

(This took me months & months and I want other people to benefit. Check back soon for a public release!)

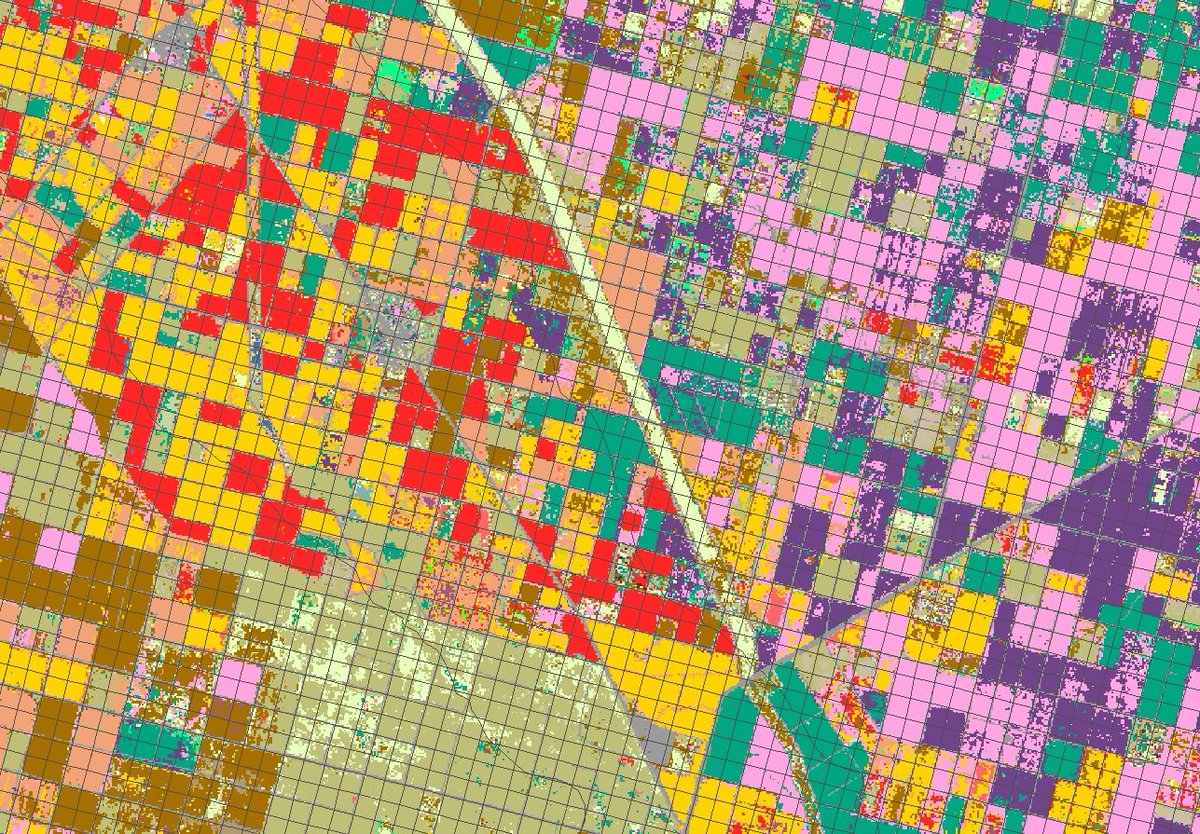

I couple my water dataset with high-resolution satellite data product from the USDA, the Cropland Data Layer. It identifies what crop is grown at every point in a 30-meter grid.

In total I have 3 billion pixels to work with

In total I have 3 billion pixels to work with

What I find is that long-run water scarcity has substantial negative effects.

Places with less water have less land in crop production

Places with less water have less land in crop production

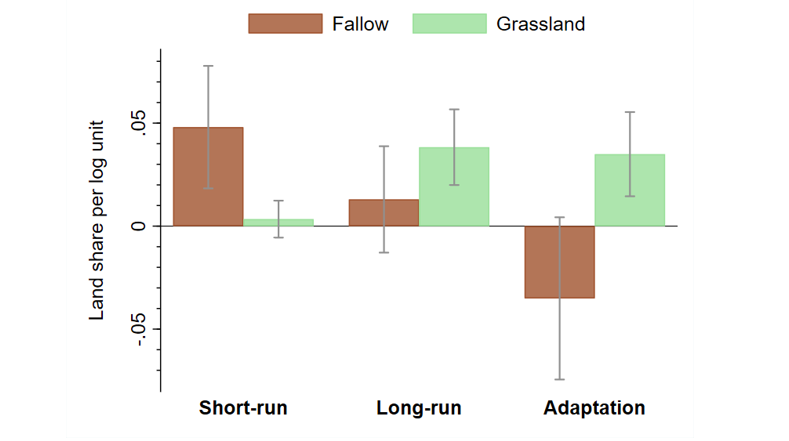

There’s a fair amount of adaptation, in terms of land use.

In response to short-run scarcity, farmers hold cropland idle/fallow.

In response to long-run scarcity, they put it into grassland (which they can at least use to graze livestock).

In response to short-run scarcity, farmers hold cropland idle/fallow.

In response to long-run scarcity, they put it into grassland (which they can at least use to graze livestock).

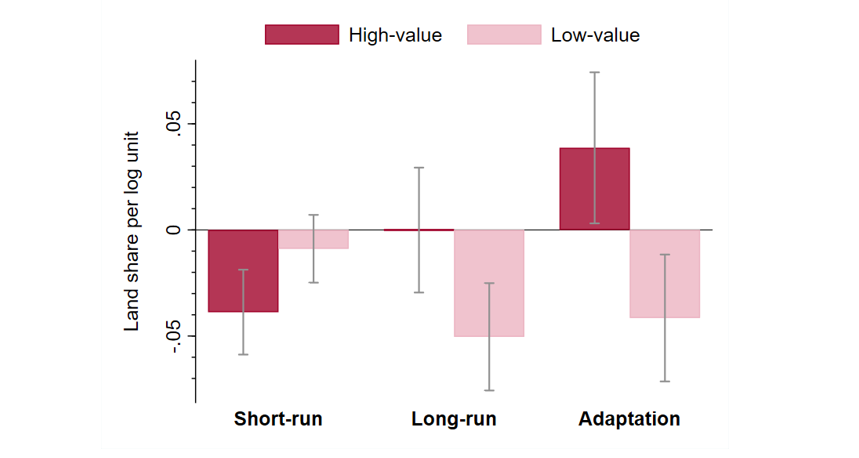

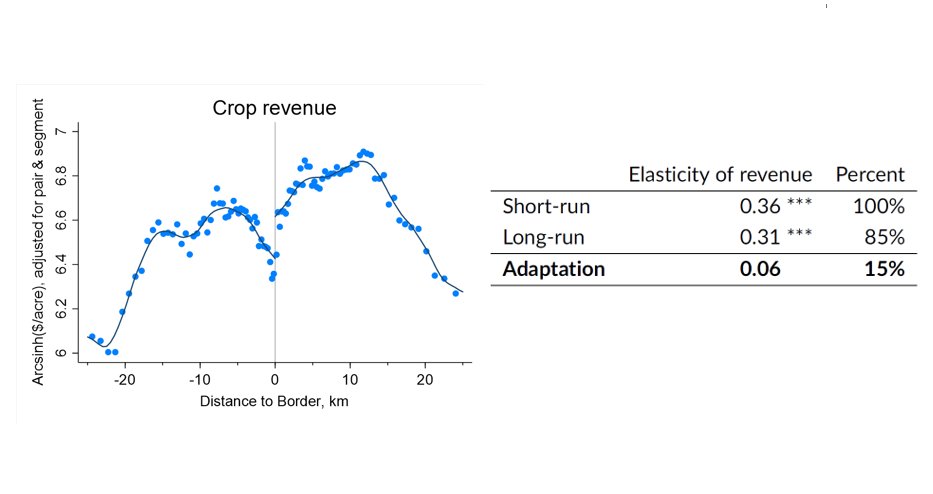

But what does this adaptation translate to in terms of revenue? Not much, it turns out.

Water scarcity reduces the revenue value of land-use choices -- by nearly as much in the long run as in the short run.

In terms of economic impacts, adaptation looks pretty limited.

Water scarcity reduces the revenue value of land-use choices -- by nearly as much in the long run as in the short run.

In terms of economic impacts, adaptation looks pretty limited.

Full climate projections are tricky to do here. What we do know is that surface water supplies are going to decline in California and many other parts of the world

So these results imply we’re likely to see reductions in ag& #39;s footprint and total output in the coming decades.

So these results imply we’re likely to see reductions in ag& #39;s footprint and total output in the coming decades.

The full paper has lots more cool results (comments welcome)

And it& #39;s part of a broader research agenda on the role of natural resources in how we cope with environmental change

For more, see my website: https://www.nickhagerty.com/

Or">https://www.nickhagerty.com/">... contact me for an interview at ASSA! https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😉" title="Winking face" aria-label="Emoji: Winking face">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="😉" title="Winking face" aria-label="Emoji: Winking face">

And it& #39;s part of a broader research agenda on the role of natural resources in how we cope with environmental change

For more, see my website: https://www.nickhagerty.com/

Or">https://www.nickhagerty.com/">... contact me for an interview at ASSA!

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter Job Market Paperhttps://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🚨" title="Police cars revolving light" aria-label="Emoji: Police cars revolving light">Can we adapt to environmental change?How important is surface water to the economy?I make progress on these questions in "The Scope for Climate Adaptation: Evidence from Water Scarcity in Irrigated Agriculture"Paper: https://www.nickhagerty.com/research&..." title="https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🚨" title="Police cars revolving light" aria-label="Emoji: Police cars revolving light">Job Market Paperhttps://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🚨" title="Police cars revolving light" aria-label="Emoji: Police cars revolving light">Can we adapt to environmental change?How important is surface water to the economy?I make progress on these questions in "The Scope for Climate Adaptation: Evidence from Water Scarcity in Irrigated Agriculture"Paper: https://www.nickhagerty.com/research&..." class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

Job Market Paperhttps://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🚨" title="Police cars revolving light" aria-label="Emoji: Police cars revolving light">Can we adapt to environmental change?How important is surface water to the economy?I make progress on these questions in "The Scope for Climate Adaptation: Evidence from Water Scarcity in Irrigated Agriculture"Paper: https://www.nickhagerty.com/research&..." title="https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🚨" title="Police cars revolving light" aria-label="Emoji: Police cars revolving light">Job Market Paperhttps://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🚨" title="Police cars revolving light" aria-label="Emoji: Police cars revolving light">Can we adapt to environmental change?How important is surface water to the economy?I make progress on these questions in "The Scope for Climate Adaptation: Evidence from Water Scarcity in Irrigated Agriculture"Paper: https://www.nickhagerty.com/research&..." class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>