Today on "things that wouldn& #39;t be allowed today"...this signal arrangement. A thread.

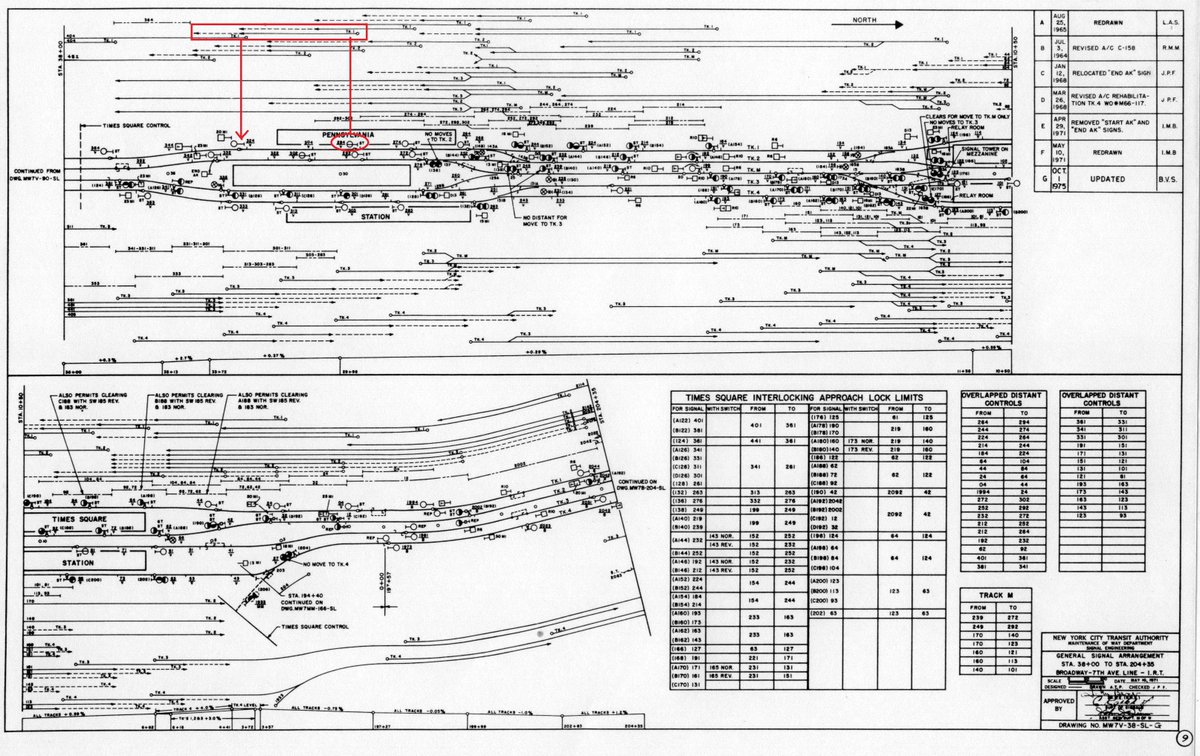

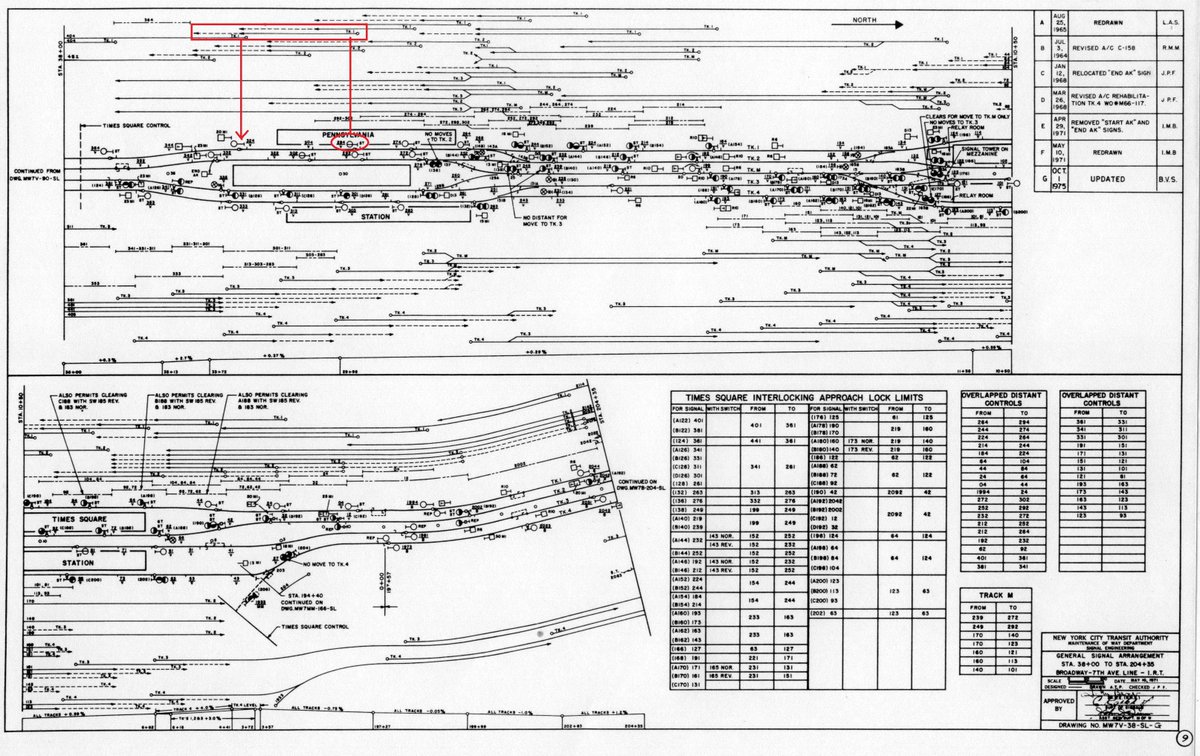

Focus on the circled signal and the boxed line above. The boxed line indicates the distance ahead of the signal which, if occupied, makes the signal red. This is called a "control line"

Focus on the circled signal and the boxed line above. The boxed line indicates the distance ahead of the signal which, if occupied, makes the signal red. This is called a "control line"

In the case of the circled signal, that line has two parts: a solid portion and a dotted portion. What& #39;s important to understand is that occupancy in dotted stretch can be allowed (signal = yellow) if the train approaching the signal is moving below a given speed.

...so, if there& #39;s a train whose rear end is somewhere in the dotted portion, I can pull into the platform at Penn, creep up on the signal, see it clear, and then pull all the way into the platform no problem.

But let& #39;s look closely here. Note that once the dotted portion has been cut away, there is no signal between the circled signal and the end of its solid control line -- the solid portion ends at the next signal along the track, the one that has an arrow pointing at it.

This means that, theoretically, I could approach the circled signal slowly, clear it and cut back the dotted portion, and then accelerate at full power without anything to stop me before I hit a train in front. A diagram, bc 280 chars is never enough:

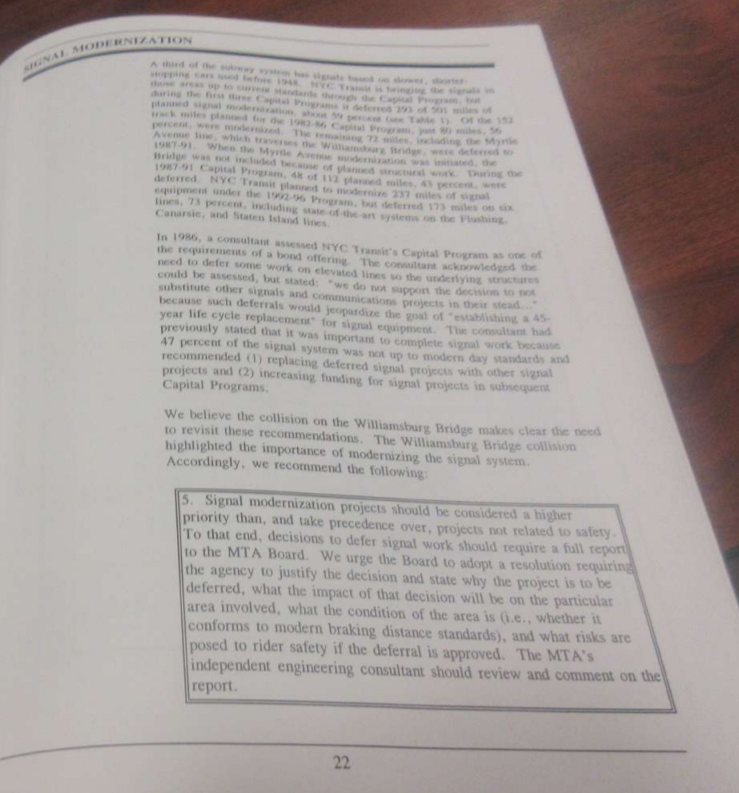

These sorts of safety deficiencies were once accepted in NYC. The logic went that if a train cleared a conditional timer, cutting back a control line, it was obviously under the control of someone who wouldn& #39;t do something crazy like accelerating at full power.

But then we had Union Sq and the W& #39;burg Bridge, where those assumptions about operator behavior were proven to be tragically incorrect. So NYCT changed its standards to correct for these deficiencies and others, and undertook a retrofit program to correct them where they existed.

(side note: a full understanding of the dimensions/implications of USQ and WB would require an even longer thread on the history of train acceleration, braking and signal design assumptions in NYC; it suffices to say that those issues follow a similar ish arc as this one)

That program is what gave us, among other things, the proliferation of timer signals. Which is to say that whether timers were installed to correct for this sort of deficiency or another, there was indeed a reason for the trains to be slowed down.

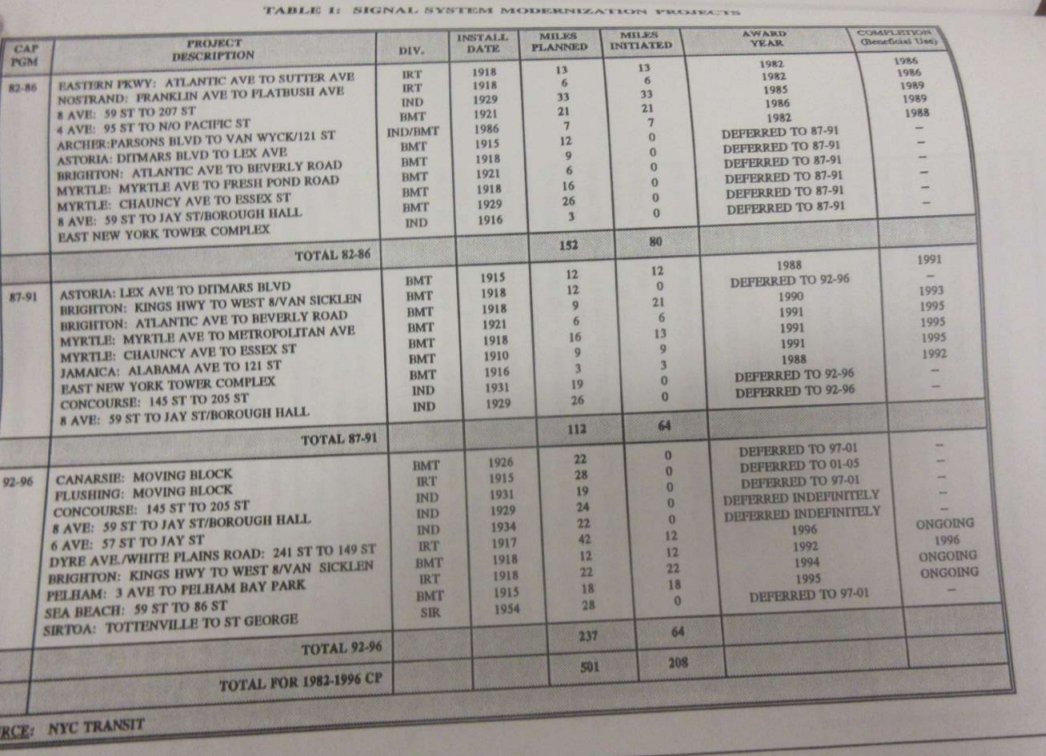

Even though we& #39;ve sorta come to terms w/ the speed issue, it& #39;s important we recognize that the issue with signal mods was not that they were an unreasonable effort, but instead that a) they were value engineered to w/in an inch of their lives, making them that much worse for svc

b) they were surrounded by an operational culture of fear, which increased their service impact far beyond the engineering estimate.

c) they were all designed with the understanding that these deficient, not-up-to-modern-standards signal systems would be shortly replaced with CBTC/modernized fixed blocks.

The installation schedule from the end of a (truly damning) MTAIG report on braking issues that played a huge role in the Williamsburg Bridge accident:

The distinction between "timers are bad" and "timers were a somewhat well intentioned program that fell victim to bureaucratic shortsightedness and culture issues" is an extremely important one as the system plays with transformation.

The former is an indictment of a process in its entirety and suggests a simplicity of problem and a degree of malice on the part of the agency; the latter illustrates a nuanced breakdown of internal agenda, planning and communication.

Understanding these causes on a fine scale makes it both easier to speak a language the agency can understand, and easier to target the exact sorts of reforms that the agency& #39;s situation demands. This is why you should care.

As for the signal issue, this is IMO the strongest case for CBTC there is: if we want a subway that doesn& #39;t suffer from reduced capacity and speed but we want a subway that& #39;s safe (and mind you there are still many mods that have yet to be done), we& #39;ve gotta resignal.

Now, for the 3 of you who read through this thread in its entirety. Enjoyed it? http://NYCsubway.org"> http://NYCsubway.org has the above diagram and many others at the bottom of this page:

https://www.nycsubway.org/wiki/Historical_Maps

An">https://www.nycsubway.org/wiki/Hist... explainer on how to read them is here:

https://www.nycsubway.org/wiki/Subway_Signals:_Single-Line_Signal_Diagrams">https://www.nycsubway.org/wiki/Subw...

https://www.nycsubway.org/wiki/Historical_Maps

An">https://www.nycsubway.org/wiki/Hist... explainer on how to read them is here:

https://www.nycsubway.org/wiki/Subway_Signals:_Single-Line_Signal_Diagrams">https://www.nycsubway.org/wiki/Subw...

#feelingmotivated this morning, so here’s some more on these issues. First up, the tradeoff between safety and speed.

It isn’t a perfect tradeoff. There’s a third variable in the equation, which is train acceleration. Whether or not a signal is deemed safe basically boils down to a question of whether or not a train tripped by it can stop before a collision, so acceleration rates matter a lot.

Brake rates are somewhat the more important of the two acceleration rates (positive and negative). How fast a train can stop determines how fast it can go when passing a given signal which determines whether or not a mod is needed/whether or not we need to reduce + acceleration

(Acceleration moss being exactly what happened post-WillyB when we realized large portions of the signal system couldn’t protect trains with contemporary acceleration and braking performance)

As I’m sure y’all have experienced, subway trains can brake quickly, so you’d expect those braking distances to be short. But signal system designs don’t assume braking at the normal rate.

They have to assume the worst case scenario conditions for braking to ensure safety — so slippery rails, some number of cars without functioning brakes, etc.

Following a test in the late 90s where NYCT sprayed a mix of propylene glycol and water on the express tracks of the Fulton line and then ran braking simulations, NYCT settled on a guaranteed brake rate of -1.4 miles per hour per second.

This is less than half of unadjusted brake rate, which usually will yield braking in the 3-4mphps range. I do not question the need for a worst case number, but I do think it’d be worth retesting to see whether modern equipment/test conditions could raise that figure.

So that’s one nuance I’d like to add. The second is a more extensive discussion of the value engineering issue with signal mods, which IMO is the most underreported facet of that story.

Basically the issue works like this. Say you have some sort of safety issue in an interlocking (an area with switches) and you, a signal engineer, have devised a complex plan that would fix it while preserving safety — lengthen a control line here, add a dotted portion here, etc.

Then your boss comes to you. “The signal mods budget has once again been cut, and spread over even more capital programs” (what happened). So the complicated work you were planning to fix the area cannot happen. But you still have to do _something_ about the safety issue.

...1 shots being among the cheapest but most operationally impactful means of fixing a signal safety issue. 1 shot mods are an important driver of the 4/5’s plight in Brooklyn, causing endless pain for @2AvSagas and kin, but ofc can be found all over the system.

This is all to say that we suffer a worse system today because of signal disinvestment in the past. Don’t! Skimp! On! Signals! Folks.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter