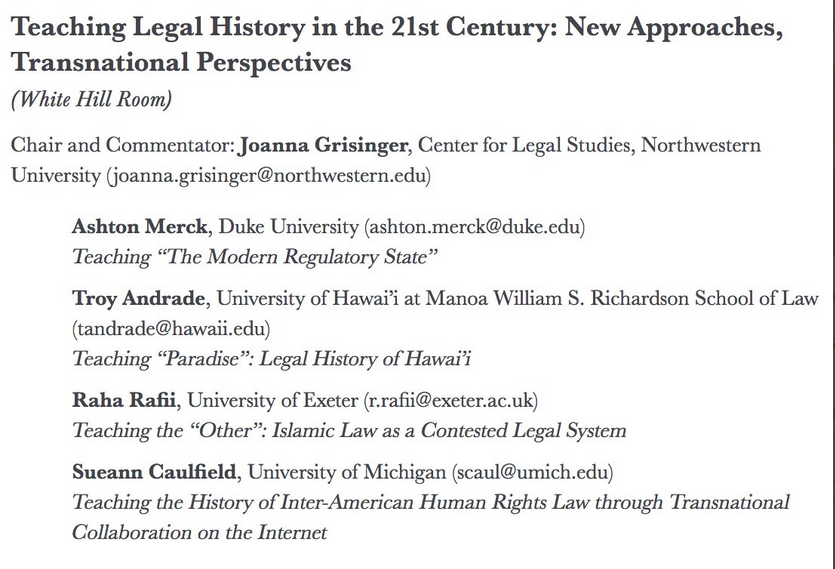

Had a great time talking about strategies and challenges of teaching Islamic law on the wonderful panel "Teaching Legal History in the 21st Century" at #ASLH2019. Some points I brought up for discussion about pedagogy of Islamic law in the university classroom:

Since anything in this country with “Islamic” in the title is contested, ESPECIALLY Islamic law, as a teacher you always have to address the general orientalist characterization of Islamic law as a barbaric, top-down system. How to do that?

I taught a course--Women, Gender, and Empire in the Middle East—that was open to all majors, all of whom had little to no background in Islamic or legal studies. Since the course was not specifically focused on Islamic law, I had to find a concise and accessible way...

...to introduce the historic flexibility of Islamic jurisprudence to undergrads who reflexively thought that one could "look up" Islamic law in a single book, find a rule, and then just apply it like a legal code

so I utilized a mock trial role play, where students were assigned the roles of plaintiff, defendant, witnesses, judge & mufti;the first 3 roles were given brief back stories, and the judge given some sources from Shafi& #39;i juristic texts, Quran, & hadith, the mufti gets a few more

The judge would have to establish the facts of the case by asking questions of the witnesses, the defendant and the plaintiff, and was allowed to consult the mufti on finding the relevant legal principles – but then would have to give a verdict on their own

Using case studies in class is not new, but assigning students particular roles in a mock trial was a great success in demonstrating how individual agents affected and impacted the decision-making process in an Islamic judicial context, more so than assigning academic articles

students also got a better, firsthand understanding of judicial discretion, and that judicial decision-making in an Islamic context is neither robotic nor arbitrary

Of course, despite the success (and the students& #39; enjoyment) of the exercise, which accounted for very little time specifically dedicated to discussions of Islamic jurisprudence, challenges remain

“Islamic law” as a phrase is unrestricted by place or time,

and thus can contribute to the orientalist notion of its unchanging timelessness, as well as to its artificial separation from a variety of social, historical, and legal contexts

and thus can contribute to the orientalist notion of its unchanging timelessness, as well as to its artificial separation from a variety of social, historical, and legal contexts

I tried to account for this by giving a case that was specifically rooted in 12th century Baghdad, but by doing so run into another challenge: students understanding one case as characterizing all of Islamic law

The role play also made me consider how a few simple tweaks (w/other kinds of cases) could also integrate complex ideas of multiple jurisdictions (mazalim v. shari& #39;a court); instead of staging the role play in the court,begin with litigants/political authority choosing the forum

Also, can integrate thinking about the impact of the presence or absence of a modern nation-state context by including cases that are affected by modern state constitutions...brings up questions about when we refer to law as "Iraqi" "Senegalese" or "Indonesian" versus "Islamic"

But another challenge remains in focusing on textual jurisprudence, which then can be misunderstood to stand in for all of "Islamic law" - so the question remains: how can a "decolonized" course on Islamic law reasonably integrate the multiplicity of Islamic legal traditions...

while acknowledging the historical reality that Muslims have always been subject to other forms of law at the same time? how do we define "law" when it traverses state admin, interpersonal relations, and devotional aspects like prayer?

The way you approach these—or even whether you bring them up—will depend on focus of the course and amount of time (semester? week? day?) dedicated to parsing and discussing Islamic law, and the types of students (undergrad, Islamic studies majors, JDs, other grad students)

Meanwhile, some great discussion from the panel: How do you use primary sources?

For things like the role play, I use them for the legal sources available to the judge and mufti. However, as a teacher you need to be aware that depending on what’s available in English translation

For things like the role play, I use them for the legal sources available to the judge and mufti. However, as a teacher you need to be aware that depending on what’s available in English translation

...translated primary sources can lead to reinforcement of ideas of law as only existing in Arabic, and of Sunni sources as normative to the exclusion of other traditions

In the course in general, though, I use translated primary sources in other genres, such as poetry, to show how the law functions as a narrative about categories of people (e.g. concubines), and how it is distinct from narratives produced by those people themselves (poetry)

A great question from an audience member to the panel: do you use legal fictional works in your teaching?

My 1st thought, an excellent idea (I had to read works of fiction in my Middle East history classes as an undergrad) but nothing really available for the earlier periods. BUT

My 1st thought, an excellent idea (I had to read works of fiction in my Middle East history classes as an undergrad) but nothing really available for the earlier periods. BUT

remembered @waraqamusa is currently filling this void with her historical fiction writing, which includes her meticulous research on courts in the earlier periods of Islamic history!

So many more issues about pedagogy of Islamic law than covered here (we had 8 minutes each to speak, with a few more for questions) but would love to see more discussions and collaborations on teaching Islamic law in a university context

Forgot to add: it was really important that the title of the panel said “Transnational” rather than “International” perspectives, since Islamic law is not a fundamentally foreign tradition to a US context through Muslim community engagement...

...In my class I assigned readings to talk about how contemporary Muslims engage with Islamic law as minority communities, but this can definitely be integrated into role-play from a bottom-up perspective along the model @idris_razan brought up https://twitter.com/idris_razan/status/1198471703275483141">https://twitter.com/idris_raz...

As a final assignment, to put what we learned about Islamic law in class into perspective (and to assess students& #39; understanding of the material), I had students critique the famous 2013 Pew Poll on "The World& #39;s Muslims," specifically "Beliefs about Sharia"...

...and how problematic it is to ask questions about "sharia" as "the law of the land" to Muslims in 24 countries under the guise of statistic objectivity in the form of polling, and without...

...and without any real understanding of how such a broad question could mean vastly different things to Muslims in war-torn countries with destroyed civil institutions v. those involved in post-colonial self-determination and identity politics, and everything in between

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter