The response of the low-carb community to studies showing that low-carb consistently associates with worse outcomes:

"But there were almost no subjects in the study that were low-carb enough."

Here is why that response is (partly) invalid. Thread.

"But there were almost no subjects in the study that were low-carb enough."

Here is why that response is (partly) invalid. Thread.

It& #39;s worth pointing out that this is exactly how plant-based people respond when you point out in plant-based diet studies that vegans/vegetarians didn& #39;t live longer than non-vegans/vegetarians:

"But there were not enough vegans/the vegans ate like crap."

"But there were not enough vegans/the vegans ate like crap."

OK now onto why this way of arguing is invalid.

First of all, it is a No True Scotsman fallacy:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/No_true_Scotsman">https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/No_t...

First of all, it is a No True Scotsman fallacy:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/No_true_Scotsman">https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/No_t...

The fallacy-

Person A: "No Scotsman puts sugar on his porridge."

Person B: "But my uncle Angus is a Scotsman and he puts sugar on his porridge."

Person A: "But no true Scotsman puts sugar on his porridge."

Person A: "No Scotsman puts sugar on his porridge."

Person B: "But my uncle Angus is a Scotsman and he puts sugar on his porridge."

Person A: "But no true Scotsman puts sugar on his porridge."

Compare-

Person A: "Studies show that low-carbohydrate diets are healthy."

Person B: "But the epidemiology shows a consistent association of low-carbohydrate diets with poor health, suggesting that they are not healthy."

Person A: "But no true low-carbohydrate is unhealthy."

Person A: "Studies show that low-carbohydrate diets are healthy."

Person B: "But the epidemiology shows a consistent association of low-carbohydrate diets with poor health, suggesting that they are not healthy."

Person A: "But no true low-carbohydrate is unhealthy."

Here why this is a fallacy:

Because everyone knows darn well that if the study showed that low-carb people live just as long or longer at a moderate-carbohydrate intake, the low-carb community would be trumpeting the study near and far.

Because everyone knows darn well that if the study showed that low-carb people live just as long or longer at a moderate-carbohydrate intake, the low-carb community would be trumpeting the study near and far.

But when an apparently negative effect is found, the study is dismissed and the goalposts moved.

This is a kind of cherry-picking, or of ad hoc hypothesis modification to avoid falsification, or of goalpost moving.

All names for the same intellectually dubious move.

This is a kind of cherry-picking, or of ad hoc hypothesis modification to avoid falsification, or of goalpost moving.

All names for the same intellectually dubious move.

The intellectually honest move is to scratch one& #39;s chin and ask:

1. Maybe there is something potentially worrisome about these low-carbohydrate diets?

2. Could lower-carbohydrate diets avoid this problem?

3. What are the limitations of this kind of study? Reverse causation?

1. Maybe there is something potentially worrisome about these low-carbohydrate diets?

2. Could lower-carbohydrate diets avoid this problem?

3. What are the limitations of this kind of study? Reverse causation?

Actually, there is no clear interpretation of nutritional epidemiological studies that suggest a negative effect of low-carbohydrate diets, and all of these interpretations are valid.

The problem is in coming to a single interpretation and ignoring all others, when we cannot definitively do that. In fact, all interpretations should be considered when we assess risk and benefit to patients. (If we really care about patients, not ideologies...)

Assuming that low-carbohydrate diets really do increase mortality, should something magical happen whereby that increase in mortality is reversed to a decrease in mortality when carbohydrate intake gets low enough?

It& #39;s possible, but what strikes us as more likely?

What strikes me as more likely is that as carbohydrate intake gets lower, we will see still further increases in mortality.

Or at least, the increase in mortality might be attenuated. Not dramatically reversed.

What strikes me as more likely is that as carbohydrate intake gets lower, we will see still further increases in mortality.

Or at least, the increase in mortality might be attenuated. Not dramatically reversed.

But I& #39;m open to the opposite interpretation as well. I just think it would be the shocking one.

I get it. Ketones are beneficial. But...

I get it. Ketones are beneficial. But...

I am studying one of the major mechanisms of action for ketones on the body& #39;s cells. I& #39;m sold that ketones are potentially beneficial.

But not sold enough that I think they are so magical that they will completely reverse a dose-response mortality curve.

But not sold enough that I think they are so magical that they will completely reverse a dose-response mortality curve.

It is worth pointing out that carbohydrate restriction does not suddenly result in a huge drop in insulin secretion when carbohydrate gets low enough. Insulin tends to fall with the extent of carbohydrate restriction.

So the mechanism would have to be ketogenesis per se. Are ketones so magical that they would reverse all of the pathophysiology (whatever is causing it) that is apparently being caused by the low-carbohydrate diet?

Another consideration: ARIC showed that while an animal-based low-carbohydrate diet is associated with higher mortality, a plant-based low-carbohydrate is associated with lower mortality.

This suggests that the problem is the animal products, not carbohydrate restriction per se.

This suggests that the problem is the animal products, not carbohydrate restriction per se.

We have a number of potential mechanisms for explaining the potential negative effects of a high-animal product diet on mortality.

None of these mechanisms by which animal products might increase morality are going to be plausibly "neutralized" by the presence of ketones.

And even if they were, wouldn& #39;t we expect for the absence of such biological effects (i.e. a plant-based low-carbohydrate diet) + ketones to be even better?

This is all pretty speculative, so let& #39;s get onto the next and perhaps critical point:

Those who make the argument that low-carbohydrate diets in these studies were not low-carb enough are often themselves low-carb proponents. And...

Those who make the argument that low-carbohydrate diets in these studies were not low-carb enough are often themselves low-carb proponents. And...

Such proponents have been responsible for the growth of low-carbohydrate dieting for the past several decades.

Yet they have, according to the studies, been entirely unable to convince more than a small % of the population to eat very-low-carbohydrate diets

Yet they have, according to the studies, been entirely unable to convince more than a small % of the population to eat very-low-carbohydrate diets

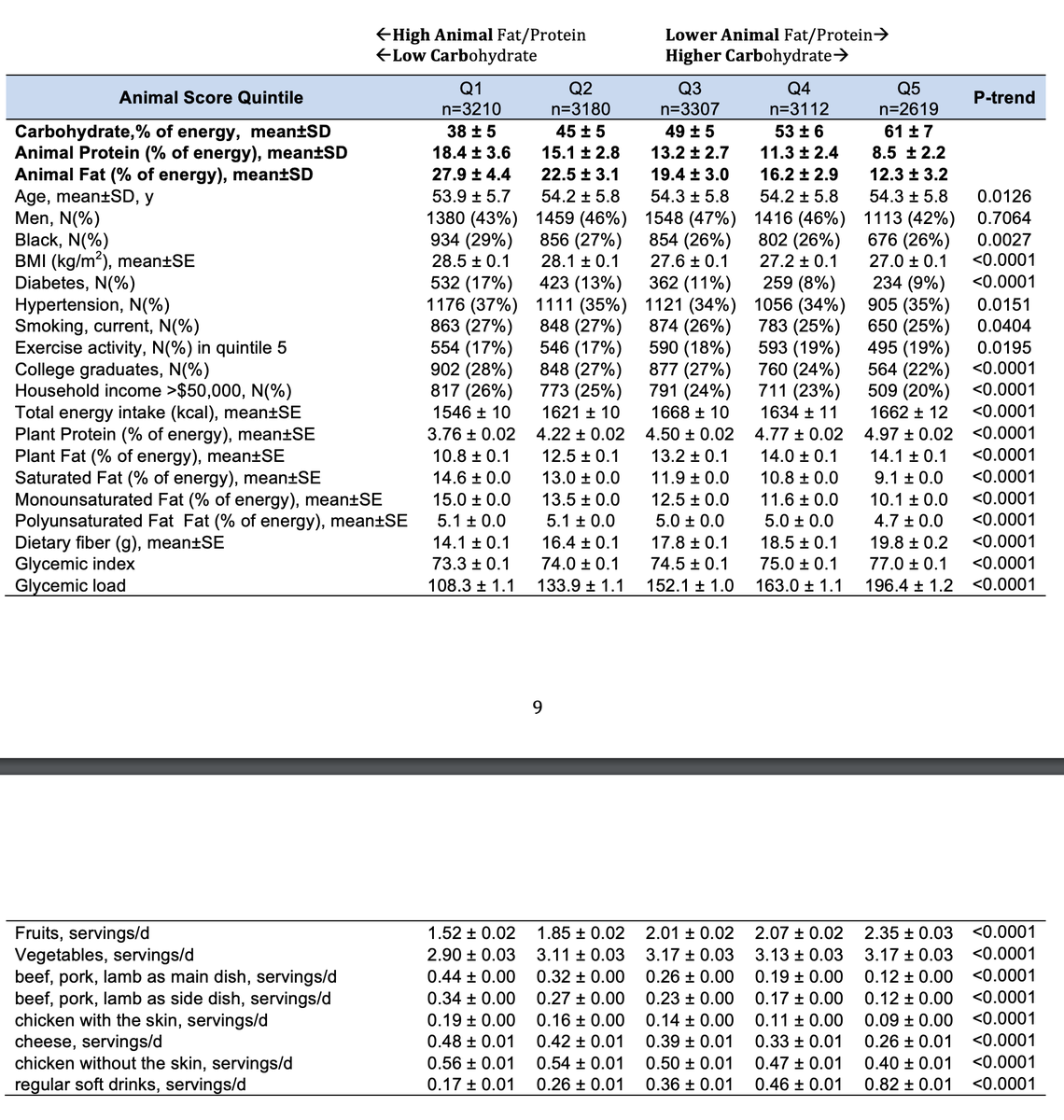

Yet very likely, a substantial number of the people in the lower-carbohydrate quantiles of these observational studies restrict their carbohydrate intake intentionally. Take a look at this last row from ARIC.

This suggests that they aren& #39;t just eating junk food diets, e.g. burgers, fries, etc. and are low-carb by coincidence (some people don& #39;t know but hamburgers are actually only ~30% carbohydrate). Instead, they are getting *more* sugary food-restricted the lower carb they go. ...

In other words, it is likely that low-carbohydrate advocacy hasn& #39;t convinced most low-carbers to go into the range of carbohydrate intake that might be associated with lower mortality, but rather into a range associated with higher mortality.

This means that the response of advocates that "they just aren& #39;t low-carb enough" is perverse!

No!

The level of carbohydrate restriction achieved by the vast majority of people is well outside the "magic" zone and is instead inside the "danger" zone.

No!

The level of carbohydrate restriction achieved by the vast majority of people is well outside the "magic" zone and is instead inside the "danger" zone.

So, low-carbohydrate diet advocates want to suggest that the problem is with their followers, not with their own ideas: if their followers almost universally restrict carbohydrate enough to be dangerous but not enough to be beneficial, it& #39;s their fault.

This is an appalling attitude, yet it is the implied position by many people who criticize these studies and say that "these people weren& #39;t low-carb enough".

It is an untenable position to take. We should be interested in real-world people, not theoretical, ideal people... We should be interested in what happens to the actual people we influence!

Even if this were not true--even if we could only be interested in the people who would be the most extreme, the biggest outliers--this would imply that ideas about ketogenic diets have little public health relevance: since hitherto, very few people have been able to follow them.

So which is it? Is low-carb dangerous? Or does it have little public health benefit in the real world, since nobody actually is able to restrict their carbs to the degree that they might need to be to derive benefit?

Thus, these epidemiology studies trap low-carb advocates in a dilemma: either low-carb diets are harmful or if they are not, it is because low-carb people don& #39;t restrict carbs enough. If they do not restrict carbs enough, then low-carb has no public health relevance.

There is one group of people for whom these studies have little relevance: clinicians.

Some clinicians might be able to persuade patients to comply to such an extent that they might indeed be able to make it into this putative magical ketogenic range where negative effects disappear.

Even in such cases however, because the evidence seems to suggest that diets higher in plants do not have the problems that diets higher in animals do, it should still be the case that clinicians should probably angle for a ketogenic diet higher in plants.

The last consideration is reverse causation or other residual confounding. While the argument that low-carb dieters in the epi literature are "not low-carb enough" ends in a dilemma, the argument about residual confounding is legitimate and much stronger.

I try to cover that argument here: https://nutritionalrevolution.org/2019/11/11/peter-attia-nutritional-epi/">https://nutritionalrevolution.org/2019/11/1...

Essentially: a diet high in (whole) plants does not carries fewer risks than one high in animal products, though the evidence is not air-tight and will not be for the foreseeable future.

Broadly speaking, I think these arguments are also applicable to the recent study suggesting that a low-carbohydrate diet produced lower HbA1c as well. https://twitter.com/kevinnbass/status/1193156784707588097">https://twitter.com/kevinnbas...

I have not responded to replies about that study due to lack of time until now. If you are still interested in this discussion, please read this thread @spencercking1 @tonytony1316131 @erik_arnesen @MatthewJDalby @MiriamBerchuk

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter